- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

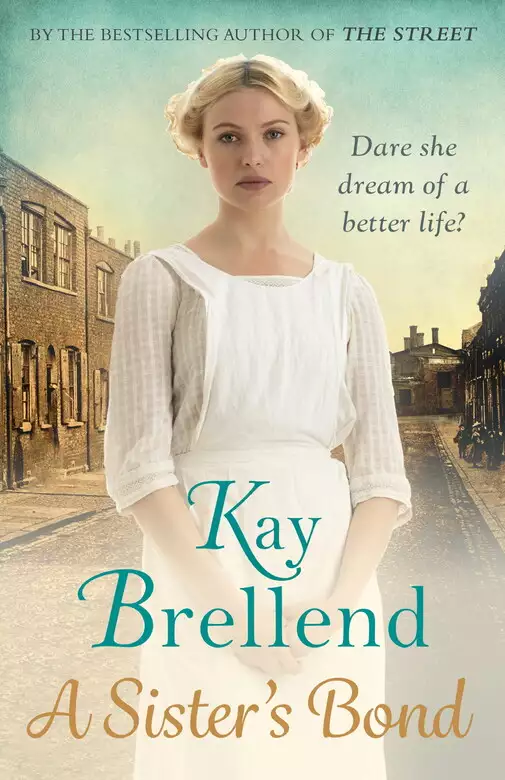

Synopsis

'Vividly rendered' Historical Novel Society ' A fantastic cast of characters' Goodreads 'Thoroughly absorbing' Goodreads Based around the WW1 female factory workers at Barratt's Sweet Factory and inspired by true stories from the author's grandmother, A Sister's Bond celebrates the everyday heroism of families who fought to survive against all odds . . . ____________________ Wood Green, North London, November 1913: The storm clouds of war gather overhead, while one brave girl fights to save her family . . . After her mother dies, Livvie Bone knows it's down to her to protect her younger siblings from their drunken father. But life on the worst street in London is dark and dangerous, and one night she needs protection herself. When the mysterious Joe Hunter steps in to help her, Livvie's fascinated by him, in spite of his unsavoury reputation. Then Livvie is offered the chance to work at the Barratt's Sweet Factory. Livvie's fragile beauty hides a formidable strength of character, and it doesn't take long for the factory manager, Lucas, to notice her. He is a sophisticated, wealthy man of the world and he can open doors to the kind of life Livvie has only dreamed of. Suddenly she has a chance to better herself - and to help her family. But time is running out, for war is approaching, sweeping everything and everyone up in its remorseless path. What life will Livvie choose - and what kind of world will be left to her when the fighting ends? ______________ A heartwarming saga about love, duty and desire by the bestselling author of The Street and East End Angel.

Release date: November 2, 2017

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Sisters Bond

Kay Brellend

‘Ain’t gonna do you no good, hiding under there. You might as well come out and take what’s coming to yer.’

The threat in that drunken voice had the small boy slithering backwards on his bottom beneath the table. His wide blue eyes were glistening but he didn’t weep. Alfie Bone had learned by now that his father, even when sober, wasn’t moved by his tears. Alfie might howl and say he was sorry but his father wasn’t given to pity.

Though his eyes were squeezed almost shut, Alfie could see in his line of vision five fidgeting fingers with potato mould beneath the ragged nails. Soon that hand would grab and hurt him.

Tommy Bone would have finished his shift down the market by midday then gone to the pub. Tommy rarely returned home before ten o’clock at night; even if his money ran out early, he’d hang around on a bar stool hoping to filch drinks off pals. But this evening he had returned hours earlier than usual, catching his son unawares.

As soon as he’d heard the key strike the lock Alfie had abandoned his supper of tea and bread and shot off the chair to wriggle beneath the table. He’d hugged himself into a small ball in his hiding place with his knees up against his chest and his nose pressed into them; even so he could smell the booze on his father’s breath.

Alfie squeaked as his safety barrier was flung noisily aside. He felt the hot trickle against his inner thigh and clenched his bony buttocks in an attempt to stop wetting himself further. He knew he’d get a taste of his father’s belt as well as a clouting for making that mess.

His father’s corduroy-clad knees bent and a bristly face appeared, making Alfie shudder and soak himself.

‘You dirty little git.’ Tommy had seen the pool of urine and drew back his lips over tobacco-stained teeth. ‘Ain’t enough that you wet the bed regular … you’ve started pissing on the floor ’n’ all.’ He snaked out a hand out to grab a hank of his son’s fair hair and haul him up. Alfie levered his heels on the bare boards, jerking himself backwards out of reach, making his father roar in frustration.

‘Leave him alone! I’ll clean that up. Get yourself to bed, Dad. You’re drunk and you’ve got to be up early in the morning for work.’

Tommy straightened up, slanting a glance over one shoulder at his eldest daughter. He’d not heard Olivia come in, so intent had he been on giving Alfie a thrashing. She had a challenging look in her eyes. But that wasn’t unusual or unexpected.

Olivia was her mother’s daughter: fine-boned and blonde-haired with the face of an angel, but delicate though she looked, she was tough and not at all frightened of him. Unlike the others, especially Alfie. Planting his fists on his hips, he stared narrow-eyed at his daughter. Olivia held her ground. She didn’t even blink. Tommy looked her over, from her buttoned boots and long serge skirt to the small neat hat set atop a thickly coiled bun of fair hair. You’d have thought she had been out with her friends rather than working behind the counter of a rough-house caff. But that was his Livvie … she kept up her standards, just like her mother had before her.

‘Turn in, Dad, you can’t stand up straight,’ Olivia said when her father’s eyelids began to flutter. Unbuttoning her coat, she hooked it on the back of the door then unpinned her hat. Taking her father’s sleeve, she attempted to pull him towards the corridor.

Tommy roughly shook her off; shuffling his feet apart for balance, he stood there swaying. ‘Don’t you go ordering me about, miss,’ he snarled. ‘I’ll get me rest after I’ve given that little bleeder a hiding.’ Tommy’s thick finger fiddled with the scarf knotted round his neck then stabbed repeatedly at the table. ‘Broken a winder round at the Catholic Mission, ain’t he? One of the nuns collared me in the pub and started asking fer money.’ Tommy’s lips were bloodless with rage. ‘Been shown up good ’n’ proper in front of me pals, and all on account of him!’ Tommy’s forefinger resumed jabbing. Having worked himself up again, he suddenly plunged one hand beneath the table to drag his son out. Olivia wrestled him back but he sent her to her knees with a sideways swipe.

Olivia now had a clear view of her seven-year-old brother and the sight of his chalky face and quaking limbs rekindled her courage, propelling her to her feet. She couldn’t let her father sense her fear. His was the sort of character that fed on another’s weakness. She’d always stood up to him and would continue to do so while she had breath left in her body to protect her siblings – especially Alfie. Their mother had never been able to protect him, but Olivia had … from the day he was born.

She dug in her skirt pocket and pulled out the wages she’d just received from the proprietor of Ward’s eel and pie shop, tipping the coins on to the splintered tabletop. ‘There, that should cover the damage to the window.’ She looked and sounded quite calm but she was carefully watching her father’s reaction. When he was seriously drunk, as now, it was difficult to know how he would react. He could blub sentimentally for his late wife or turn vicious and lash out at any of his kids, to try and ease the guilt that devoured him. But the coward took it out on his youngest child the most.

Tommy blinked, bleary-eyed, at the silver and copper. The sight of cash always had a sobering effect on him. His eldest daughter uncomplainingly handed over the majority of her wages but he knew she usually kept back some pennies that she was saving up. ‘Ain’t enough there for a new winder pane and your share of the kitty,’ he growled.

‘It’ll have to be enough for now, ’cos it’s all I’ve got. I’ll speak to the Sisters and tell them we’ll settle up the rest of what’s owed next week.’ Olivia started counting out her housekeeping, intending to put the rest back into her pocket to take to the Mission Hall.

Clumsily, Tommy Bone knocked aside his daughter’s small hand and swept all the coins into his greedy palm. ‘I’ll speak to the nosy cows, and I’ll tell ’em to send Brody round next time he’s got an axe to grind.’ Tommy hunched his shoulders into his donkey jacket. ‘Sent a woman to do a man’s job, and a nun at that!’ He spat in disgust.

Olivia attempted to steady her father as he wobbled. Again he disdained her help by shrugging her off before weaving towards the door under his own steam.

She knew that the window-pane money wouldn’t get as far as the Mission, or Father Brody. It would stay in Tommy’s pocket until spent on a pint, or a bet on the nags. But she was glad the sight of her wages had side-tracked him; he’d forgotten about Alfie, hiding under the table. Once she heard the bedroom door slam shut Olivia crouched down. She beckoned to her brother, giving him a reassuring smile. He crawled out on his hands and knees, snuffling and knuckling his damp eyes.

‘Let’s get those wet things off you,’ Olivia said on a sigh, helping him to his feet. While Alfie peeled off his sodden trousers she got a towel from the cupboard by the side of the fireplace and proceeded to briskly dry off his scrawny buttocks and legs. He winced as she rubbed over a spot on his thigh that had a healing bruise on it. Olivia soothed him, her heart squeezing tight as she turned her brother round to dry his other side and saw another purple blotch, this time on his shoulder. She swallowed the anger rising in her throat that made her want to rush to her father’s bedroom and bawl at him that he was a brute. She pressed her lips against her little brother’s shoulder, kissing it better.

‘I hate him!’ Alfie croaked, clasping his sister’s head close to his chest and starting to cry.

Olivia had heard that before, and not only from her brother. Her two sisters claimed to feel the same way. Olivia found it hard to like their father as well, but at seventeen she was learning life had a dark side and that the lines between love and hate and good and evil could be blurred. Heartache, and the never-ending struggle to scrape a living for your family, could knock all the decency out of folk. She’d seen girls she’d been friendly with at school turn into coarse tarts, hanging around the market place after dark looking for punters. Yet they’d been full of joy and hope just a few years ago. Even those kids, like her, who’d been raised hard and hungry had cherished dreams of a better future. Olivia wasn’t giving up yet, even though those dreams seemed to shift further away from her every day.

‘Stand still,’ she said as Alfie attempted to wriggle free. ‘You’ll get chapped if you don’t dry off properly.’ She put aside the towel. ‘Now find yourself some pants and a vest in the cupboard. I’ll rinse these trousers through.’ She fetched a tin bowl and began to wring the worst of the pee into it.

‘If you wash ’em they won’t dry by morning. Need ’em for school.’ Alfie was pulling on his patched vest, trembling with the cold.

It was late November and the frost had shrouded every surface outside with silver. As she’d hurried home over icy ground Olivia had imagined a poet would be inspired to write verses about nature’s sparkle. Now such flighty nonsense was forgotten.

‘I’ll rinse them. They’ll smell else and you won’t want your mates calling you names, will you?’

Blood stung Alfie’s cheeks. He’d been called Piss Pants on numerous occasions after he’d wet the bed and the stink of the sheets had lingered on his skin.

Pulling up his clean pants, he nipped to the table to wolf down what was left of his bread and gulp his cold tea.

‘Why didn’t you get to bed on time, Alfie?’ Olivia asked. ‘You know it’s best to be out of his way when he comes in.’

‘He was back early. Anyhow, I had an errand to do for Mrs Cook so didn’t get me tea on time,’ Alfie explained. ‘She asked me to fetch a bucket of coal from the corner shop. I took a few lumps off the top and put ’em in our scuttle.’

‘If she finds out she won’t ask you again,’ his sister warned. She didn’t want Alfie to think she liked what he’d done, although she recalled doing similar things herself while still at school and wanting, in her own way, to help the family out with a bit of ducking and diving.

Lifting his empty plate, Alfie retrieved his earnings hidden under it. He knew that if his father had realised the coins were there he’d have taken them. He held out the two ha’pennies to his sister. ‘You can have ’em,’ he said magnanimously. ‘Dad’s taken all of yours.’

‘Thanks.’ Olivia took the money, paltry offering though it was. She was indeed broke now and she didn’t want to have to dip too far into her small savings pot, hidden away to pay for a few Christmas treats for them all. Besides it wouldn’t hurt her brother to contribute something if he’d been causing trouble. She fixed a jaundiced eye on Alfie. ‘Did you break that window?’

‘It was an accident. It did get broke but it weren’t me done it,’ Alfie stressed. ‘I was in goal, but Wicksie booted the ball that put the glass out.’ Alfie frowned. ‘He blamed me and said it was my fault ’cos I should’ve saved it. Went way over me head, though.’ Alfie looked ashamed not to have reached the shot although he was much younger and smaller than the boy he’d been playing football with.

Olivia ruffled his hair for comfort. Tearing up a rag she’d found in the cupboard, she dropped to her hands and knees, carefully keeping her skirt away from the puddle on the floor. She didn’t want to be washing that too. ‘Make yourself useful and tip that pee down the privy then fetch me some water in the bowl.’ She started to mop the wet lino.

Alfie pulled on his battered boots then scooted off in his underwear. He returned, sloshing water. After putting down the bowl he stood at his sister’s side, quaking with cold, his shoulders hunched to his ears and his arms wrapped about himself.

Olivia stopped scrubbing the floor, pushing her blonde fringe from her eyes with one wrist. She’d forgotten it was icy outside and regretted sending him out there half dressed. Sitting back on her heels, she dried her damp hands on her skirts then rubbed some warmth into his goose-pimpled limbs until he groaned a protest.

‘Go on, get to bed now, I’ll finish up here.’ She gave him a little push towards the door. ‘Jump in with Nancy and Maggie and snuggle up. I’ll be along myself soon. I’m all in.’

The Bones had three rooms in the terraced house on Ranelagh Road that they called home. At one time they’d rented the whole property but they’d had to let the upstairs go when money got tight after Aggie Bone passed away. Their landlord had carved the hallway into two with a partition so the downstairs had its own doorway but all the occupants shared the square of corridor leading to the stairs. The family’s accommodation now consisted of just a back parlour housing a cooking range, and two front rooms used to sleep in. Tommy had taken a bedroom to himself while his four children shared the other.

Several residents had come and gone upstairs. Some had disappeared during the night after getting behind with their rent. The landlord didn’t tolerate arrears but he’d never needed to chase the Bone family. Tommy Bone did his duty by his family that far at least.

Olivia immersed the soiled trousers in the bowl, dunking them up and down a few times before leaving them to soak. She perched on the edge of a chair and let her head droop into her cupped palms. Now Alfie was safely in bed she gave way to a tiredness that wasn’t wholly to do with her having rushed home after toiling for several hours washing pots and doling out pie and mash at the caff. The constant anxiety of looking out for her brother and sisters was sapping her strength. She’d managed to defuse things this evening, just as she had on previous occasions, but there was always tomorrow and the day after that to worry about.

Despite feeling ashamed for having such thoughts, Olivia often wished her father would abandon them to bunk up with a woman, leaving them all in peace. Of course, if he did they would suffer financially. She’d struggle to raise her school-age siblings without her father’s contribution providing them with basic necessities. Mentally, Olivia balanced that disadvantage against the fact that if he wasn’t around she’d be able to bring in more. At present she worked when certain he’d also be out, reasoning that if they were at home at the same time she could keep the peace.

Like Alfie, she had been caught out by Tommy’s early return from the pub. Usually they were all, herself included, behind the closed bedroom door by the time he let himself in.

Tommy worked daytime shifts at Barratt’s sweet factory and boosted his earnings by helping out at the weekends on a market stall. For all his faults, Tommy Bone wasn’t a shirker. He liked to keep enough cash in his pocket for booze and bets and ’bacca.

Olivia started to wring out Alfie’s trousers, continuing until her wrists and knuckles ached with the effort. She hung them over the mantel, pinned there by a heavy brass candlestick. Slow drips from the material hit the metal beneath, hissing quietly on the hot hob plate. Olivia shook the scuttle. Hearing Alfie’s few purloined lumps of coal rattling at the bottom, she built up the fire in the hope the trousers would dry by the morning. After briskly rubbing her stiff fingers together she put the kettle on to boil for a cup of tea. It was all the supper she felt she could stomach.

‘What’s up, Livvie? Heard you come in a while ago. Thought you’d have come to bed by now.’

Olivia turned to see her sister Maggie entering the parlour, wrapped in her dressing gown. ‘Heard Dad come in first though, didn’t you?’

Maggie bit her lip and shrugged, looking sheepish.

‘I’ll be turning in in a minute, after I’ve had me tea,’ Olivia said. ‘Is Alfie getting off to sleep?’

‘Nah … he’s just laying there snivelling, getting on me nerves. I got up ’cos I can’t get back to sleep now he’s woken me.’

Olivia made the tea but she didn’t offer her sister a cup. Maggie was the next eldest child at almost fourteen and, although Olivia didn’t expect her to stand up to their father in the way she did herself, she believed her sister capable of protecting their little brother more than she did. Maggie and Nancy had turned in, knowing that Alfie was out on his own. It wouldn’t have hurt one of them to wait up for a short while for him to return from his errand then hurry him to bed.

Maggie sat down and cocked her head. ‘What’s got your goat? Ain’t my fault Alfie’s in Dad’s bad books again. Broken a window, ain’t he?’

‘You knew about that?’ Olivia put down her cup, surprised.

‘Ricky Wicks told me. Didn’t think the nuns would rat on him, though.’ Maggie stifled a chuckle. ‘Alfie just told me they collared Dad in the pub about it.’

‘I’m going to bed now.’ Olivia put the cup in the washing up bowl, feeling maddened that her sister could find anything amusing in what had happened.

‘Ain’t my fault Dad takes it out on Alfie, you know.’ Maggie sounded huffy.

‘Not saying it is, but our brother nearly got another hiding for something he didn’t do. You can tell Ricky Wicks that I know he put the window out and in future he should hang around with kids his own age.’

‘Tell him yerself,’ Maggie answered back. She and Ricky were in the same class; she knew he liked her and that’s why he’d let her little brother play football with him and his mates.

‘Keep your voice down or you’ll wake Dad up then you’ll be sorry.’ Olivia made an effort to subdue her annoyance. Picking up a stub of burning candle from the mantelshelf, she headed towards the door.

In the bedroom they all shared, the sound of her younger sister’s snoring made Maggie chuckle. ‘Nancy’ll suck the paper off the wall, way she’s going.’

‘What’s left of it,’ Olivia muttered as she closed the door and put the candle on the floor next to her bed. The small room stank of damp and even in the dim light rags of wallpaper could be seen drooping by the ceiling.

‘’Ere, shift over, Nance,’ Maggie hissed, climbing onto the double iron bedstead she shared with her eleven-year-old sister and Alfie. It groaned beneath her slight weight and Nancy rolled over, mumbling as she settled back to sleep.

Olivia sank onto the edge of the sagging mattress on her single bed, pushed against the opposite wall, and started to unbutton her boots. She eased them off her aching feet, flexing her toes in her woollen stockings. Quickly she took off her skirt and blouse, making sure to fold them neatly at the end of the bed before slipping on her dressing gown over her underclothes. The looming shadows of the wardrobe and nightstand made the room feel claustrophobic.

‘Can I come in with you, Livvie?’ Alfie called quietly into the darkness.

‘Yeah … come on.’

Olivia took off her dressing gown and wrapped him in it then pulled the solitary blanket up over them both, doubling it back and over Alfie to give him extra warmth. She put her arms about him, cuddling him fiercely. ‘Now go to sleep … your trousers’ll be nice and dry in the morning.’ She whispered that last comment, knowing he wouldn’t want his sister Maggie to know he’d wet himself. If she knew then so would others; she kept nothing to herself … other than that her father was a bully. But then they all did that.

With a sigh Olivia leaned down to snuff out the candle flame.

‘How you doing then, Tommy?’

‘Bearing up, mate … bearing up.’ Tommy Bone clapped Bill Morley on the shoulder in greeting then settled his cloth cap back on his head with a flourish. The two men carried on walking along Mayes Road towards Barratt’s sweet factory where they worked. In fact Tommy had a thumping head after his Sunday drinking session but he’d never let on to anybody about how he felt. Even work colleagues he’d known for over a decade found him hard to fathom. He might have a drink and a chat with them but in reality he was a loner with no close friends. The only places anybody ever saw Tommy Bone were the factory, the pub, or hanging around the bookie’s. It was well known that he was a widower with four kids but he could have been a bachelor because he was always seen on his own.

Tommy had got up for work as usual at a quarter to seven that morning. A shift at the sweet factory ran from eight in the morning to six-thirty at night and woe betide any latecomers or shirkers. The bosses expected strict timekeeping and, to be fair, they more or less stuck to the rules too.

His eldest daughter had already been up when Tommy appeared in the parlour, scratching his belly over his vest. Olivia had been lugging a basket of sheets out to the washhouse. Monday was washday and Livvie had a heavy task in front of her. Not only did she spend from early till late doing their washing and ironing, but she took in for the old girl next-door who had arthritic hands. As was his custom, Tommy didn’t stop to help his eldest carry the washing basket, or to speak to her other than to grunt a ‘mornin’’. Neither did she receive a thank-you for the modest breakfast that she had prepared for him and left under a cloth, as she did every morning before he rose for work. He drank his tea and ate his bread and jam in silence, as usual, seated at the small parlour table.

Despite his hangover, and his run in with the nun that still made him seethe when he thought about it, Tommy was in a good frame of mind as he bowled along, arms swinging at his sides. He’d remembered that the new motor van was due for a run that morning, the latest addition to the company’s transport that to date had comprised only horse-drawn vehicles. Tommy was hoping to get a crack at driving the van, being as he was one of Mr Barratt’s most loyal employees. He was the only original staff member still with the firm since it had moved from Hoxton to spanking new premises in Wood Green.

At Hoxton, Tommy had been a sugar-boiler, manufacturing the ‘stickjaw’ toffee that kids loved. He’d started work there at thirteen but it had been before his time when George Barratt Senior had accidentally hit on a novel way of making his fortune. He’d over-boiled a batch of sugar being prepared for cake confectionery. The old skinflint hadn’t wanted to waste it so had sold it on as kids’ toffee. It had gone down a treat with customers so he carried on manufacturing sweets, becoming successful enough to afford to build a sprawling new factory in North London.

‘Didn’t see you down the pub last night,’ Bill Morley said innocently as the two men carried on along the frosty street in the weak wintry dawn. ‘Dick said you’d been in but left around half-eight. Didn’t get down there meself till gone nine being as the missus burned me tea then come over all lovey-dovey to make up for it.’ Bill bit his lip to subdue a smile. He’d heard from Dick Barnes, the pub landlord, that Tommy Bone had gone off in a rage after a nun tore him off a strip on account of his lad misbehaving.

Tommy would talk the hind leg off a donkey about his job and how far back he went with the firm’s guvnors. But when it came to his home and his kids, he kept it all to himself. If it weren’t for a woman who’d once rented rooms above the Boneses letting it be known that Tommy walloped his kids, nobody would know he paid them enough attention to discipline them.

Tommy plunged his hands into the pockets of his donkey jacket, aware that Bill was winding him up. ‘You was in late Friday.’ He’d changed the subject to one he knew Morley couldn’t ignore, to get his own back. ‘You’ll get short wages for that. It ain’t the first time, is it?’

‘Was only ten minutes,’ Bill protested. ‘Weren’t my fault anyhow. I’ll have a word with Mr Black. He’s all right.’

‘He ain’t the guv’nor.’ Tommy’s voice held contempt. ‘You’ll need to suck up to the organ grinder, not the oily rag.’

Tommy didn’t like the way that Lucas Black was gaining influence in the company, though a lot of people thought it was good that the old hierarchy welcomed new blood and fresh ideas.

A posh boy Black might be, but he was sharp and fair-minded; he had put his weight behind getting the management to agree to a half-hour afternoon break for those working overtime until eight o’clock. That same week, though, he’d docked Tommy’s wages for causing an accident. Several hundredweight of boxed sweets had tumbled off the back of a cart, narrowly missing a couple of factory girls who were passing by at the time. The spooked horses had bolted, adding to the chaos, and the drama of it kept everybody talking for weeks. Tommy hadn’t liked that: he wanted to pick the topic of conversation, not be the butt of it.

Mr Barratt had kept out of the dispute, allowing his new manager to deal with the matter, and Tommy had lost half a week’s pay. Some colleagues thought it wasn’t punishment enough because it could have ended in disaster.

‘If I say that me alarm clock don’t work they’ll have to let me off. Barratt’s bought the bugger after all.’ Bill burst out laughing as they turned in at the factory gates. Most people had muttered they’d sooner have had a plum pudding as a Christmas present than a heavy-handed reminder of their bosses’ obsession with timekeeping.

A small crowd of men stood in the yard and Tommy speeded up as he saw they had congregated around the new vehicle.

He elbowed his way through to the front of the crowd to run one hand over the shiny coachwork of the pristine van. He glanced about for Mr Barratt, hoping he’d put in an appearance so Tommy could wheedle out of him the opportunity to learn to drive the motor. His eyes met Lucas Black’s and the younger man gave him a faint smile and approached.

‘Nice, isn’t it … but I reckon we’ll be needing Dobbin for a while yet. At least until we know all the pros and cons.’

‘You’ll get further afield and supply more customers with a motor, and this little beauty won’t go lame on you neither.’ Tommy crossed his arms over his chest, adopting a knowledgeable air.

‘True enough, but a horse and cart won’t need expensive maintenance.’

‘They do if some silly sod stacks the wagon wrong and pallets of liquorice hit the deck, spooking the horses.’

Tommy swung about, looking for the big-mouthed joker, his scowl making it clear he didn’t appreciate being ribbed in front of the man who’d bawled him out and lost him half a week’s wages.

‘’Least with the nags you get a free bag of manure for your allotment,’ another voice shouted from the back of the group.

‘I’d keep that quiet … he’ll dock it off yer wages,’ Tommy said with a sarcastic inflexion in his voice.

He still only grudgingly accepted that he’d done wrong that day. In his opinion he’d not been careless … or still hungover; he’d been using his initiative to cram the cart because they were a driver down that week and the extra load still had to be got out.

When the factory first opened in Mayes Road, Tommy had started on the production line. As they expanded and a lot of women were taken on, he had sought a more masculine environment in the growing transport department. That’s where he’d stayed ever since. He’d worked with the horses and in the warehouse. He’d even had a go at learning signwriting so as to decorate the sides of the carts, but hadn’t shown much skill at it. All in all, though, he liked to think he was the factory’s most versatile and indispensable employee.

But there was one person who seemed to think differently.

‘Right … that’s enough standing around. Let’s get some work done, shall we?’ Lucas Black directed the order at the group of men but his eyes returned to Tommy, and he wasn’t smiling now.

*

‘Thanks, love.’ Mrs Cook sniffed the crisply folded sheets and gave a loud exhalation. ‘Love the smell of Sunlight soap, I do.’

‘It’s certainly nicer than that pong.’ Olivia nodded her head in the direction of Barratt’s sweet factory. Day and night, a pall of sickly liquorice seemed to hang over the neighbourhood. In the summer months it was even worse and could carry for miles on the breeze.

Mrs Cook wrinkled her nose in agreement and pulled a silver coin from her apron pocket. ‘There you go … a bob for your trouble. Would you do me best tablecloth with me sheets next week, Livvie? Had me grandkids over fer Sunday tea and Nora got beetroot on it. Want to get it all crisp ’n’ clean fer Christmas Day.’

‘’Course I will,’ Olivia said.

‘’Ere … look … see her?’ Mrs Cook was nodding her head at somebody along the street. ‘You stay clear of that one, love. She’s up to no good.’

Olivia thought she recognised her and was racking her brains to recall why that was. The woman stopped at Olivia’s own house and took a key from her bag.

‘Oh … yes, Mr Silver showed her upstairs last week. He’s showed quite a few people around but I heard them grumbling about the rent he was asking.’

‘Scandalous what those Jews get away with,’ Mrs Cook snorted. ‘I’ve been waiting for the privy out the back to be fixed for nigh on a month. A plumber ain’t been near nor by. Stinks to high heaven it do … and rats running about!’

Olivia was only half listeni

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...