- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

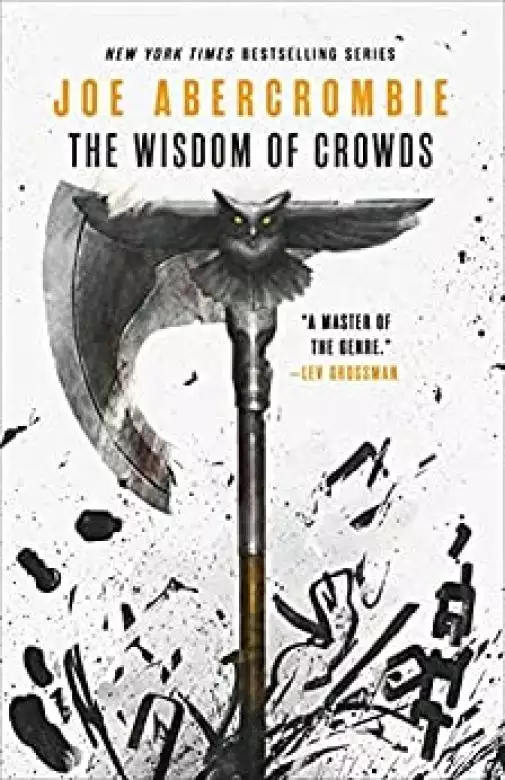

Chaos. Fury. Destruction.

The Great Change is upon us . . .

Some say that to change the world you must first burn it down. Now that belief will be tested in the crucible of revolution: the Breakers and Burners have seized the levers of power, the smoke of riots has replaced the smog of industry, and all must submit to the wisdom of crowds.

With nothing left to lose, Citizen Brock is determined to become a new hero for the new age, while Citizeness Savine must turn her talents from profit to survival before she can claw her way to redemption. Orso will find that when the world is turned upside down, no one is lower than a monarch. And in the bloody North, Rikke and her fragile Protectorate are running out of allies . . . while Black Calder gathers his forces and plots his vengeance.

The banks have fallen, the sun of the Union has been torn down, and in the darkness behind the scenes, the threads of the Weaver's ruthless plan are slowly being drawn together . . .

"A master of his craft." —Forbes

"No one writes with the seismic scope or primal intensity of Joe Abercrombie." —Pierce Brown

For more from Joe Abercrombie, check out:

The Age of Madness

A Little Hatred

The Trouble With Peace

The Wisdom of Crowds

The First Law Trilogy

The Blade Itself

Before They Are Hanged

Last Argument of Kings

Best Served Cold

The Heroes

Red Country

The Shattered Sea Trilogy

Half a King

Half a World

Half a War

Release date: September 14, 2021

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 640

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wisdom of Crowds

Joe Abercrombie

The corporal’s lightly bloodshot eyes slid towards Orso. “Your Majesty?”

“I must confess to feeling rather pleased with myself.”

The Steadfast Standard rippled on the breeze, its white horse rampant and its golden sun aglitter, the name of Stoffenbeck already stitched among the famous victories it had witnessed. How many High Kings had ridden triumphant beneath that gleaming scrap of cloth? And now—despite being outnumbered, derided and widely written off—Orso had joined their ranks. The man the pamphlets once dubbed the Prince of Prostitutes had emerged, like a splendid butterfly from a putrid chrysalis, as the new Casamir! Life takes strange turns, all right. The lives of kings especially.

“You damn well should feel pleased with yourself, Your Majesty,” frothed Lord Marshal Rucksted, and few men knew more about feeling pleased with themselves than he. “You out-thought your enemies off the battlefield, out-fought ’em on it and took the worst traitor of the lot prisoner!” And he stole a self-satisfied glance over his shoulder.

Leo dan Brock, that hero who a few days ago had seemed too big a man for the world to hold, was now contained in a miserable wagon with barred windows, bumping along in Orso’s wake. But then there was less of him to contain than there used to be. His ruined leg had been buried on the battlefield alongside his ruined reputation.

“You won, Your Majesty,” piped up Bremer dan Gorst, then snapped his mouth shut, frowning off towards the approaching towers and chimneys of Adua.

“I did, didn’t I.” An unforced smile was creeping across Orso’s face, all by itself. He could hardly remember the last time that happened. “The Young Lion, beaten bloody by the Young Lamb.” His clothes just seemed to fit him better than they had before the battle. He rubbed at his jaw, left unshaven for a few days in all the excitement. “Should I grow a beard?”

Hildi pushed back her oversized cap to doubtfully assess his stubble. “Can you grow a beard?”

“It’s true I’ve often failed in the past. But one could say that about a great many things, Hildi. The future looks a different sort of place!”

For perhaps the first time in his life he was eager to find out what the future might hold—even to grapple with the bastard and force it into the shapes he desired—so he had left Lord Marshal Forest bellowing the battle-mauled Crown Prince’s Division back into order and ridden ahead for Adua with a hundred mounted men. He needed to get to the capital and set the ship of state on course. With the rebels crushed, he could finally embark on his grand tour of the Union and greet his subjects as a royal winner. He could find out what he could do for them, how he could make things better. He wondered fondly what name the adoring crowds would roar at him. Orso the Steadfast? Orso the Resolute? Orso the Dauntless, the Stone Wall of Stoffenbeck?

He sat back, rocked gently by the saddle, and took a deep breath of the crisp autumn air. Since a northerly breeze was carrying the vapours of Adua out to sea, he didn’t even need to cough afterwards.

“I finally understand what people mean when they say they feel like a king.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t worry,” said Tunny. “I’m sure you’ll feel baffled and helpless again before you know it.”

“Doubtless.” Orso could not help glancing towards the rear of the column yet again. The wounded Lord Governor of Angland was not their only significant captive. Behind the Young Lion’s prison wagon rattled the heavily guarded carriage containing his heavily pregnant wife. Was that Savine’s pale hand gripping the windowsill? The mere thought of her name made Orso wince. When the only woman he had ever loved married another man, then betrayed him, he had fondly imagined he could feel no worse. Then he learned she was his half-sister.

The smell of the haphazard slums outside the walls of Adua hardly reduced his sudden nausea. He had pictured smiling commoners, little Union flags waved by freckled children, showers of perfumed petals from beauties on the balconies. He had always turned his nose up at such patriotic guff when it was directed at other victors, but he had been rather looking forward to its being directed at him. Instead, ragged figures frowned from the shadows. A harlot chewing a chicken leg laughed from a misshapen window. One ill-favoured beggar very noticeably spat into the road as Orso trotted past.

“There will always be malcontents, Your Majesty,” murmured Yoru Sulfur. “Only ask my master. No one ever thanks him for his pains.”

“Mmmm.” Though as far as Orso could recall, Bayaz was always treated with the heights of servile respect. “What’s his solution?”

“To ignore them.” Sulfur considered the slum-dwellers without emotion. “Like ants.”

“Right. Don’t let them spoil the mood.” But it was a little late for that. The wind seemed to have turned chilly, and Orso was developing that familiar worried prickling at the back of his neck.

The wagon grew even gloomier. Its clattering wheels began to echo. Beyond the barred window Leo saw cut stone rush past, knew they must be riding through one of Adua’s gates. He’d dreamed of entering the capital at the head of a triumphant parade. Instead he came locked in a prison wagon stinking of stale straw, wounds and shame.

The floor jolted, sent a throb of agony through the stump of his leg, squeezed tears from his raw eyes. What a fucking fool he’d been. The advantages he’d tossed away. The chances he’d let slip past. The traps he’d blundered into.

He should’ve told that treacherous coward Isher to fuck himself the moment his prattle tilted towards rebellion. Or better yet, gone straight to Savine’s father and spilled the whole story to Old Sticks. Then he’d still have been the Union’s most celebrated hero. The champion who beat the Great Wolf! Not the dunce who lost to the Young Lamb.

He should’ve swallowed his pride with King Jappo. Flattered and flirted and played the diplomat, offered Westport with a giggle, swapped that worthless offcut of Union territory for all the rest and landed in Midderland with Styrian troops behind him.

He should’ve brought his mother. The thought of her begging on the docks made him want to rip his hair out. She’d have pressed that shambles on the beach into order, taken one calm glance at the maps and set the men flowing southwards, got to Stoffenbeck first and forced the enemy into a losing battle.

He should’ve sent his reply to Orso’s dinner invitation on the end of a lance, attacked with every man before sunset and swept the lying bastard from the high ground, torn up his reinforcements as they arrived.

Even as Leo’s left wing misfired and his right wing crumbled, he could’ve called off that final charge. At least he’d still have Antaup and Jin. At least he’d still have his leg and his arm. Perhaps Savine could’ve teased out some deal. She was the king’s ex-lover, after all. From what Leo had seen at his own execution, likely his current one, too. He couldn’t even blame her. She’d saved his life, hadn’t she? Whatever his life was worth now.

He was a prisoner. A traitor. A cripple.

The wagon had slowed to a juddering crawl. He heard voices up ahead, chanting, ranting. King Orso’s loyal subjects, come out to cheer his victory? But it sounded nothing like a celebration.

The training circle had been Leo’s dance floor. Now it was an ordeal just to straighten the leg he still had, so he could grasp the bars of the window with his good hand and drag himself up. By the time he felt the chill breeze on his face and squinted out into a street murky with foundry smoke, the wagon had shuddered to a halt.

Strange details jumped at him. Shop shutters smashed, broken doors hanging from hinges, rubbish scattered across the road. He thought a heap of rags in a doorway might be a sleeping tramp. Then, with a creeping worry that made him forget his own pain for a moment, he started to think it might be a corpse.

“By the dead,” he whispered. A warehouse had been burned out, its charred rafters like the ribs of a picked-over carcass. A slogan was daubed across its blackened front in letters three strides high.

The Time is Now.

He pressed his face to the bars, straining to see further up the street. Beyond the officers, retainers and Knights of the Body on their nervous horses, figures were crowded outside a spike-topped wall, banners bobbing over the mob like standards over a regiment. Fair pay for fair work and Down with the Closed Council and Rise up! They were already drifting towards the king’s column, droning with sullen anger, booing and jeering. Were these… Breakers?

“By the dead,” he whispered again. He saw people down a side street, too. Men with labourer’s clothes and clenched fists. Running figures, chasing someone. Falling on them, kicking and punching.

A bellow came from up ahead. Rucksted, maybe. “Clear the way, in the name of His Majesty!”

“You clear the fucking way!” snarled a man with a thick beard and no neck at all. People were filtering in from the alleys, creating a troubling sense of the column being surrounded.

“It’s the Young Lion!” someone barked, and Leo heard half-hearted cheers. His good leg, which a few days ago had been his bad leg, was on fire, but he clung to the bars as people crowded towards the wagon, hands reaching for him.

“The Young Lion!”

Savine watched from the carriage window, utterly helpless, one hand clutching her bloated mass of belly, the other gripping Zuri’s, while ruffians crowded around Leo’s prison wagon like pigs around a trough. She hardly knew whether they were trying to rescue or murder him. Probably they had no idea, either.

She realised she could not remember how it felt, not to be scared.

It had probably begun as a strike. Savine knew every manufactory in Adua, and this was Foss dan Harber’s paper mill, a concern she had twice declined to invest in. The profits were tempting, but Harber’s reputation stank. He was the kind of brutal, exploitative owner who made it hard for everyone else to properly exploit their workers. It had probably begun as a strike then turned, as strikes quickly can, into something altogether uglier.

“Get back!” snapped a young officer, lashing at the crowd with his riding crop. A mounted guard dragged one man away by the shoulder, then clubbed another across the scalp with his shield. Blood showed bright as he fell.

“Oh,” said Savine, her eyes going wide.

Someone hit the officer with a stick and rocked him in his saddle.

“Wait!” She thought it might have been Orso’s voice. “Wait!” But it made no difference. The High King of the Union was suddenly as powerless as she was. People pressed in on every side, a sea of furious faces, shaken placards and clenched fists. The clamour made her think of Valbeck, of the uprising, but the terrible present was bad enough without reaching for the terrible past.

More soldiers rode in. A cry cut off as someone was trampled.

“Bastards!”

A faint ring as a blade was drawn.

“Protect the king!” came Gorst’s shriek.

A soldier struck out with the pommel of his sword, then with the flat, knocking a man’s cap off and sending him tumbling to the cobbles. One of the other Knights of the Body was less forbearing. A flicker of steel, a high-pitched scream. This time, Savine saw the sword fall and open a yawning wound in a man’s shoulder. Something smashed against the side of the carriage and she flinched.

“God help us,” muttered Zuri.

Savine stared at her. “Does He ever?”

“I keep hoping.” Zuri slid a protective arm around Savine’s shoulders. “Come away from the window—”

“And go where?” whispered Savine, shrinking back against her.

Beyond the glass it was utter chaos. A mounted soldier and a red-faced woman wrestled over one end of a banner that read All Equal, the other tangled up in a mass of arms and faces. A Knight of the Body was dragged from his horse, lost in the crowd like a sailor in a stormy sea. They were everywhere, forcing their way between the horses, shoving, clutching, screeching.

A crash as the window shattered and Savine jerked back, broken glass showering in.

“Traitor!” someone screamed. At her? At Leo? An arm hooked through, a dirty hand fishing for the catch. Savine smashed at it clumsily with the side of her fist, not sure whether it would be worse to be dragged from the carriage by the mob or dragged to the House of Questions by the Inquisition.

Zuri was just getting up when there was a flicker outside. Something pattered Savine’s cheek. Red spots on her dress. The arm slithered away. Fire bloomed suddenly beyond the window and she hunched over, both arms around her belly as pain stabbed through her guts.

“God help us,” she mouthed. Would she give birth there, on the glass-littered floor of a carriage in the middle of a riot?

“You fuckers!” A big man in an apron had caught the reins of that blonde girl Orso kept as a servant, the one who used to carry messages between him and Savine, a thousand years ago. He clutched at her leg while she kicked back, spitting and snarling. Savine saw Orso wrench his horse around and start punching the man about his balding scalp. He grabbed at Orso, trying to pull him down from his saddle. “You—”

His skull burst open, spraying red. Savine stared. She could have sworn that man Sulfur had slapped him with an open hand and torn his head half-off.

Gorst spurred past, teeth bared as he hacked savagely on one side then the other, bodies dropping. “The king!” he squealed. “The king!”

“The Agriont!” someone bellowed. “Stop for nothing!”

The carriage lurched forwards. Savine would have been thrown from her seat had Zuri not shot out an arm. She clung desperately to the empty window frame, bit her lip at another flash of pain in her swollen stomach.

She saw people scatter. Heard shrieks of terror. A body was knocked reeling by the corner of the carriage, clattered against the door and went down under the milling hooves of a knight herald. There were strands of blonde hair caught in the broken window.

Wheels bounced over a trampled sign, whirred over pamphlets stuck flapping to the damp road. The prison wagon clattered ahead, striking sparks from the cobbles, maddened horses all around, whipping manes and flapping harness. Something clonked against the other side of the carriage, then they were past, leaving Harber’s mill and its rioting workers behind.

Cold wind rushed through the broken window, Savine’s heart hammering, her hand frozen on the sill but her face burning as if she’d been slapped. How could Zuri be so calm beside her? Her face fixed, her arm so firm around Savine. The baby squirmed as the carriage rocked and jolted. It was alive, at least. It was alive.

Outside the window she saw Lord Chamberlain Hoff clinging to his reins, chain of office tangled tight around his red throat. She saw the king’s old, grey-haired standard-bearer gripping his flagstaff, the sun of the Union streaming overhead, an oily smear across the cloth of gold.

Streets whipped by, so familiar, so unfamiliar. This city had been hers. No one more admired. No one more envied. No one more hated, which she had always taken as the only honest compliment. Buildings flashed past. Buildings she knew. Buildings she owned, even. Or had owned.

It would all be forfeit now.

She squeezed her eyes shut. She could not remember how it felt, not to be scared.

She remembered taking Leo’s ring, with the Agriont and all its little people spread out beneath them. The future had been theirs. How could they have so totally destroyed themselves? His recklessness or her ambition alone could not have done it. But like two chemicals which, apart, are merely mildly poisonous, combined they had produced an unstable explosive which had blown both their lives and thousands of others to hell.

The cut beneath the bandages on her shaved head itched endlessly. Perhaps it would have been kinder if the chunk of metal that scarred her had flown just a little lower and split her skull instead of just her scalp.

“Slow!” Gorst’s squealing voice. “Slow!” They were crossing one of the bridges into the Agriont, the great walls looming ahead. Once they had made her feel safe as a parent’s embrace. Now they looked like prison walls. Now they were prison walls. Her neck was not out of the noose yet, and nor was Leo’s.

After they brought him down from the gallows, she had changed the dressing on his leg. It seemed the sort of thing a wife should do for her wounded husband. Especially when his wounds were in large part her doing. She had thought she could be strong. She was notorious for cool ruthlessness, after all. But as she unwound the bandages in an obscene striptease they had gone from spotted brown, to pink, to black. The stump revealed. The dressmaker’s nightmare of clumsy stitching. The weeping purple-redness of the jagged seams. The terrible, bizarre, fake-looking absence of the limb. The cheap spirits and butcher-shop stench of it. She had covered her mouth. Not a word said, but she had looked into his face and seen her own horror reflected, then the guards had come to take her away, and she had been grateful. The memory made her sick. Sick with guilt. Sick with disgust. Sick with guilt at her disgust.

She realised she was shivering, and Zuri squeezed her hand. “It will be all right,” she said.

Savine stared into her dark eyes and whispered, “How?”

The carriage juddered to a halt. When an officer opened the door, glass tinkled from the broken window. It took a moment to make her fingers unclench. She had to peel them away, like the death grip of a corpse. She wobbled down in a daze, thinking she would piss herself with every movement. Had she pissed herself already?

The Square of Marshals. She had wheeled her father across this expanse of flagstones once a month, laughing at the misfortunes of others. She had attended Open Council at the Lords’ Round, sifting the blather for opportunities. She had discussed business with associates, who to raise up, who to grind down, who to pay off and who would pay the price. She knew the landmarks above the soot-streaked rooftops—the slender finger of the Tower of Chains, the looming outline of the House of the Maker. But they belonged to a different world. A different life. All around her men goggled in disbelief. Men with faces grazed, fine uniforms torn, drawn swords stained red.

“Your hand,” said Zuri.

It was smeared with blood. Savine turned it stupidly over and saw a shard of glass stuck into her palm, where she had been gripping the window frame. She hardly even felt it.

She glanced up, and her eyes met Orso’s. He looked pale and rattled, his golden circlet skewed, his mouth slightly open as if to speak, hers slightly open as if to reply. But for a while they said nothing.

“Find Lady Savine and her husband some quarters,” he croaked, eventually. “In the House of Questions.”

Savine swallowed as she watched him walk away.

She could not remember how it felt, not to be terrified.

Orso strode across the Square of Marshals in the rough direction of the palace, fists clenched. The sight of her still somehow took his breath away. But there were more pressing concerns than the smouldering ruins of his love life.

That his homecoming triumph had degenerated from anticlimax into bloodbath, for instance.

“They hate me,” he muttered. He was used to being despised, of course. Scurrilous pamphlets, slanderous rumours, sneers in the Open Council. But for a king to be politely loathed behind his back was the normal state of society. For a king to be physically manhandled by a crowd was a short step from outright revolt. The second in a month. Adua—the centre of the world, the zenith of civilisation, that beacon of progress and prosperity—was plunged into lawless chaos.

It was quite the shocking disappointment. Like popping some delightful sweetmeat into one’s mouth and, upon chewing, discovering it was actually a piece of shit. But that was the experience of being a monarch. One shocking mouthful of shit after another.

Lord Hoff was wheezing away as he struggled to keep up. “There are always… complaints—”

“They fucking hate me! Did you hear them cheering for the Young Lion? When did that entitled bastard become some man of the people?” Before Orso’s victory, everyone had considered him a contemptible coward and Brock a magnificent hero. By rights, surely, their positions should have been reversed. Yet now he was considered a contemptible tyrant, while they cheered the Young Lion as a pitiable underdog. If Brock had wanked in the street it would have been to thunderous approval from the public.

“Bloody traitors!” snarled Rucksted, grinding gloved fist into gloved palm. “We should hang the bloody lot of them!”

“You can’t hang everyone,” said Orso.

“With your permission, I’ll head back into the city and make a damn good start at it.”

“I fear our mistake has been too many hangings rather than too few—”

“Your Majesty!” A knight herald of horrifying height was waiting on the Kingsway beneath the statue of Harod the Great, winged helmet under one arm. “Your Closed Council has urgently requested your attendance in the White Chamber.” He fell in step beside Orso, having to shorten his stride considerably. “Might I congratulate you on your famous victory at Stoffenbeck?”

“That feels a very long time ago,” said Orso, stalking on. He was concerned that if he did not keep moving, he might collapse like a child’s tower of bricks. “I have already received the congratulations of a considerable crowd of rioters on the Kingsway.” And he frowned up at the looming statue of Casamir the Steadfast, wondering whether he had ever been obliged to flee from his own people through the streets of his own capital. The history books made no mention of it.

“Things have been… unsettled in your absence, Your Majesty.” Orso did not care for the way he said unsettled. It felt like a euphemism for something much worse. “There was a disturbance shortly after you left. Over the rising price of bread. With the rebellion, and the poor weather, not enough flour has been getting into the city. A crowd of women forced their way into some bakers’ shops. They beat the owners. One they declared a speculator, and… murdered.”

“This is troubling,” said Sulfur, with towering understatement. Orso noticed he was carefully wiping blood from the side of his hand with a handkerchief. Of the slight smirk he had managed to maintain through the execution of two hundred people outside Valbeck, there was no sign at all.

“The next day there was a strike at the Hill Street Foundry. The day after there were three more. Some guardsmen refused to patrol. Others clashed with the rioters.” The knight herald worked his mouth unhappily. “Several deaths.”

Orso’s father was last in the procession of immortalised monarchs, gazing out over the deserted park with an expression of decisive command he had never worn in life. Opposite him, on a slightly less monumental scale, loomed that famous war hero Lord Marshal West, that noted torturer Arch Lector Glokta, and the First of the Magi himself, glaring down with wrinkled lip as though all men were complaining ants to him indeed. Orso had often wondered which retainers would end up opposite his own statue, in future years. This was the first time he had ever wondered if he would get a statue at all.

“There’ll be order now!” Hoff struggled to lift the funereal mood. “You’ll see!”

“I hope so, Your Grace,” said the knight herald. “Groups of Breakers have taken over some of the manufactories. They march openly in the Three Farms, calling for… well, the resignation of His Majesty’s Closed Council.” Orso did not care for the way he said resignation. It felt like a euphemism for something considerably more final. “People are stirred up, Your Majesty. People want blood.”

“My blood?” muttered Orso, trying and failing to loosen his collar.

“Well…” The knight herald gave a rather limp parting salute. “Blood, anyway. I’m not sure they care whose.”

It was a sadly reduced Closed Council that struggled to its aged feet as Orso clattered into the White Chamber. Lord Marshal Forest had been left behind in Stoffenbeck with the shattered remnants of the army. Arch Lector Pike was terrifying the ever-restless denizens of Valbeck into renewed submission. A replacement had yet to be found for High Justice Bruckel after his head was split in half during a previous attempt on Orso’s life. Bayaz’s chair at the foot of the table was—as it had been for the great majority of the last few centuries—empty. And the surveyor general, one could only assume, was once again out with his bladder.

Lord Chancellor Gorodets’ voice was rather shrill. “Might I congratulate Your Majesty on your famous victory at Stoffenbeck—”

“Put it out of your mind.” Orso flung himself into his uncomfortable chair. “I have.”

“We were set upon!” Rucksted stormed to his seat with spurs jingling. “The royal party!”

“Rioters in the bloody streets of Adua!” wheezed Hoff as he sagged down and began to dab his sweat-beaded forehead with the sleeve of his robe.

“Bloody streets indeed,” murmured Orso, wiping his cheek with his fingertips and seeing them come away lightly smeared with red. Gorst’s handiwork had left him speckled all over. “Any news from Arch Lector Pike?”

“You haven’t heard?” Gorodets had graduated from his usual habit of fluffing and combing his long beard to wringing it between clawing fingers. “Valbeck has fallen to an uprising!”

The glug of Orso swallowing echoed audibly from the stark white walls. “Fallen?”

“Again?” squealed Hoff.

“No word from His Eminence,” said Gorodets. “We fear he may be a captive of the Breakers.”

“Captive?” muttered Orso. The room was feeling even more intolerably cramped than usual.

“News of turmoil pours in from all across Midderland!” blurted the high consul, warbling on the edge of panic. “We have lost contact with the authorities in Keln. Troubling news from Holsthorm. Robbings. Lynchings. Purges.”

“Purges?” breathed Orso. It appeared he was doomed to endlessly repeat single words in a tone of horrified upset.

“There are rumours of bands of Breakers ravaging the countryside!”

“Huge bands,” said Lord Admiral Krepskin. “Converging on the capital! Bastards have taken to calling ’emselves the People’s Army.”

“A bloody plague of treason,” breathed Hoff, eyes fixed on the empty chair at the bottom of the table. “Can we get a message to Lord Bayaz?”

Orso dumbly shook his head. “Not soon enough to make a difference.” He imagined the First of the Magi would choose to keep a discreet distance in any case, while calculating how he could profit from the aftermath.

“We have done all we can to keep the news from becoming public—”

“To prevent panic, you understand, Your Majesty, but—”

“They may be at our gates within days!”

There was a long silence. The sense of triumph as Orso approached the city was a dimly remembered dream.

If there was a polar opposite to feeling like a king, he had discovered it.

“You must confess,” said Pike. “It’s impressive.”

“I must,” said Vick. And she wasn’t easily impressed.

The People’s Army might have lacked discipline, equipment and supplies, but there was no arguing with its scale. It stretched off, clogging the road in the valley bottom and straggling up the soggy slopes on both sides, until it was lost in the drizzly distance.

There might’ve been ten thousand when they set out from Valbeck. A couple of regiments of ex-soldiers had formed the bright spearhead, gleaming with new-forged gifts from Savine dan Brock’s foundries. But order soon gave way to ragged chaos. Mill workers and foundry workers, dye-women and laundry-women, cobblers and cutlers, butchers and butlers, dancing more than marching to old work songs and drums made from cookpots. A largely good-natured riot.

Vick had half-expected, half-hoped that they’d melt away as they slogged across the muddy country in worsening weather, but their numbers had quickly swelled. In came labourers, smallholders and farmers with scythes and pitchforks—which caused some concern—and with flour and hams—which caused some celebration. In came gangs of beggars and gangs of orphans. In came soldiers, deserted from who knew what lost battalions. In came dealers, whores and demagogues, dishing up husk, fucks and political theory in tents by roadways trampled into bogs.

There was no arguing with its enthusiasm, either. At night, the fires went on for miles, folk drawing dew-dusted blankets tight against the autumn chill, blurting out their smoking dreams and desires, talking bright-eyed of change. The Great Change, come at last.

Vick had no idea how far back that sodden column went now. No idea how many Breakers and Burners were part of it. Miles of men, women and children, slogging through the mud towards Adua. Towards a better tomorrow. Vick had her doubts, of course. But all that hope. A flood of the damn stuff. No matter how jaded you were, you couldn’t help but be moved by it. Or maybe she wasn’t quite so jaded as she’d always told herself.

Vick had learned in the camps that yo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...