- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

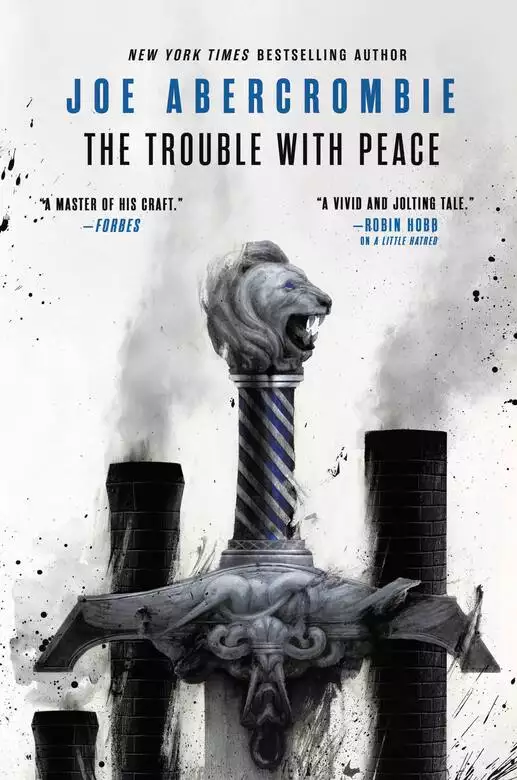

The sequel to the New York Times bestselling A Little Hatred from epic fantasy master Joe Abercrombie.

Conspiracy. Betrayal. Rebellion.

Peace is just another kind of battlefield . . .

Savine dan Glokta, once Adua's most powerful investor, finds her judgement, fortune and reputation in tatters. But she still has all her ambitions, and no scruple will be permitted to stand in her way.

For heroes like Leo dan Brock and Stour Nightfall, only happy with swords drawn, peace is an ordeal to end as soon as possible. But grievances must be nursed, power seized and allies gathered first, while Rikke must master the power of the Long Eye . . . before it kills her.

Unrest worms into every layer of society. The Breakers still lurk in the shadows, plotting to free the common man from his shackles, while noblemen bicker for their own advantage. Orso struggles to find a safe path through the maze of knives that is politics, only for his enemies, and his debts, to multiply.

The old ways are swept aside, and the old leaders with them, but those who would seize the reins of power will find no alliance, no friendship, and no peace lasts forever.

For more from Joe Abercrombie, check out:

The Age of Madness

A Little Hatred

The Trouble With Peace

The First Law Trilogy

The Blade Itself

Before They Are Hanged

Last Argument of Kings

Best Served Cold

The Heroes

Red Country

The Shattered Sea Trilogy

Half a King

Half a World

Half a War

Release date: September 15, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Trouble With Peace

Joe Abercrombie

The moment he sat they began to drag out their own chairs, wincing as old backs bent, grunting as old arses settled on hard wood, grumbling as old knees were eased under the tottering heaps of paper on the table.

“Where’s the surveyor general?” someone asked, nodding at an empty chair.

“Out with his bladder.” There was a chorus of groans.

“One can win a thousand battles.” Lord Marshal Brint worried at that lady’s ring on his little finger, gazing into the middle distance as though at an opposing army. “But in the end, no man can defeat his own bladder.”

As the youngest in the room by some thirty years, Orso ranked his bladder among his least interesting organs. “One issue before we begin,” he said.

All eyes turned towards him. Apart from those of Bayaz, down at the foot of the table. The legendary wizard continued to gaze out of the window, towards the palace gardens which were just beginning to bud.

“I am set on making a grand tour of the Union.” Orso did his best to sound authoritative. Regal, even. “To visit every province. Every major city. When was the last time a monarch visited Starikland? Did my father ever go?”

Arch Lector Glokta grimaced. Even more than usual. “Starikland was not considered safe, Your Majesty.”

“Starikland has always been afflicted with a restless temper.” Lord Chancellor Gorodets was absently smoothing his long beard into a point, fluffing it up, then smoothing it again. “Now more than ever.”

“But I have to connect with the people.” Orso thumped the table to give it emphasis. They needed some feeling in here. Everything in the White Chamber was cold, dry, bloodless calculation. “Show them we’re all part of the same great endeavour. The same family. It’s supposed to be a Union, isn’t it? We need to bloody unite.”

Orso had never wanted to be king. He enjoyed it even less than being crown prince, if that was possible. But now that he was king, he was determined to do some good with it.

Lord Chamberlain Hoff tapped at the table in limp applause. “A wonderful idea, Your Majesty.”

“Wonderful,” echoed High Justice Bruckel, who had the conversational style of a woodpecker and a beak not dissimilar. “Idea.”

“Noble sentiments, well expressed,” agreed Gorodets, though his appreciation did not quite reach his eyes.

One old man fussed with some papers. Another frowned into his wine as though something had died in it. Gorodets was still stroking his beard, but now looked as if he could taste piss.

“But?” Orso was learning that in the Closed Council there was always at least one but.

“But…” Hoff glanced to Bayaz, who gave permission with the slightest nod. “It might be best to wait for a more auspicious moment. A more settled time. There are so many challenges here which require Your Majesty’s attention.”

The high justice puffed out a heavy breath. “Many. Challenges.”

Orso delivered something between a growl and a sigh. His father had always despised the White Chamber and its hard, stark chairs. Despised the hard, stark men who sat on them. He had warned Orso that no good was ever done in the Closed Council. But if not here, where? This cramped, stuffy, featureless little room was where the power lay. “Are you suggesting the machinery of government would grind to a halt without me?” he asked. “I think you over-sugar the pudding.”

“There are issues the monarch must be seen to attend to,” said Glokta. “The Breakers were dealt a crippling blow in Valbeck.”

“A hard task well done, Your Majesty,” Hoff drooled out, with cloying sycophancy.

“But they are far from eradicated. And those that escaped have become… even more extreme in their opinions.”

“Disruption among the workers.” High Justice Bruckel rapidly shook his bony head. “Strikes. Organising. Attacks on staff and property.”

“And the damn pamphlets,” said Brint, to a collective groan.

“Damn. Pamphlets.”

“Used to think education was merely wasted on the commoners. Now I say it’s a positive danger.”

“This bloody Weaver can turn a phrase.”

“Not to mention an obscene etching.”

“They incite the populace to disobedience!”

“To disaffection!”

“They talk of a Great Change coming.”

A flurry of twitches ran up the left side of Glokta’s wasted face. “They blame the Open Council.” And published caricatures of them as pigs fighting over the trough. “They blame the Closed Council.” And published caricatures of them fucking each other. “They blame His Majesty.” And published caricatures of him fucking anything. “They blame the banks.”

“They promote the ridiculous rumour that the debt… to the Banking House of Valint and Balk… has crippled the state…” Gorodets trailed off, leaving the room in nervous silence.

Bayaz finally tore his hard, green eyes from the window to glare down the table. “This flood of disinformation must be stemmed.”

“We have destroyed a dozen presses,” grated Glokta, “but they build new ones, and smaller all the time. Now any fool can write, and print, and air their opinions.”

“Progress,” lamented Bruckel, rolling his eyes to the ceiling.

“The Breakers are like bloody moles in a garden,” growled Lord Marshal Rucksted, who had turned his chair slightly sideways-on to give an impression of fearless dash. “You kill five, pour a celebratory glass, then in the morning your lawn’s covered in new bloody molehills.”

“More irritating than my bladder,” said Brint, to widespread chuckling.

Glokta sucked at his empty gums with a faint squelch. “And then there are the Burners.”

“Lunatics!” snapped Hoff. “This woman Judge.”

Shudders of distaste about the table. At the notion of such a thing as a woman, or at the notion of this particular one, it was hard to say.

“I hear a mill owner was found murdered on the road to Keln.” Gorodets gave his beard a particularly violent tug. “A pamphlet nailed to his face.”

Rucksted clasped his big fists on the table. “And there was that fellow choked to death with a thousand copies of the rule-sheet he distributed to his employees…”

“One might almost say our approach has made matters worse,” observed Orso. A memory of Malmer drifted up, legs dangling from his cage as it swung with the breeze. “Perhaps we could make some gesture. A minimum wage? Improved working conditions? I heard a recent fire in a mill led to the deaths of fifteen child workers—”

“It would be folly,” said Bayaz, his attention already back on the gardens, “to obstruct the free operation of the market.”

“The market serves the interests of all,” offered the lord chancellor.

“Unprecedented,” agreed the high justice. “Prosperity.”

“No doubt the child workers would applaud it,” said Orso.

“No doubt,” agreed Lord Hoff.

“Had they not been burned to death.”

“A ladder is of no use if all the rungs are at the top,” said Bayaz.

Orso opened his mouth to retort but High Consul Matstringer got in first. “And we face a veritable cornucopia of adversaries overseas.” The coordinator of the Union’s foreign policy had never yet failed to confuse complexity with insight. “The Gurkish may still be embroiled in all-encompassing predicaments of their own—”

Bayaz gave a rare grunt of satisfaction at that.

“But the Imperials endlessly rattle their swords on our western border, exhorting the populace of Starikland to continued disloyalty, and the Styrians are emboldened in the east.”

“They are building up their navy.” Lord Admiral Krepskin roused himself for a heavy-lidded interjection. “New ships. Armed with cannon. While ours rot in their docks for lack of investment.”

Bayaz gave a familiar grunt of dissatisfaction at that.

“And they are busy in the shadows,” went on Matstringer, “sowing discord in Westport, enticing the Aldermen to sedition. Why, they have succeeded in scheduling a vote within the month which could see the city secede from the Union!”

The old men competed to display the most patriotic outrage. It was enough to make Orso want to secede from the Union himself.

“Disloyalty,” grumbled the high justice. “Discord.”

“Bloody Styrians!” snarled Rucksted. “Love to work in the shadows.”

“We can work there, too,” said Glokta softly, in a manner that made the hairs prickle beneath Orso’s braid-heavy uniform. “Some of my very best people are even now ensuring Westport’s loyalty.”

“At least our northern border is secure,” said Orso, desperate to inject some optimism.

“Well…” The high consul crushed his hopes with a prim pursing of the mouth. “The politics of the North are always something of a cauldron. The Dogman is advanced in years. Infirm. No man can divine the fate of his Protectorate in the event of his death. Lord Governor Brock would appear to have forged a strong bond with the new King of the Northmen, Stour Nightfall—”

“That has to be a good thing,” said Orso.

Doubtful glances were traded across the table.

“Unless their bond becomes… too strong,” murmured Glokta.

“The young Lord Governor is popular,” agreed Gorodets.

“Damned,” pecked the high justice. “Popular.”

“Handsome lad,” said Brint. “And he’s earned a warrior’s reputation.”

“Angland behind him. Stour as an ally. Could be a threat.”

Rucksted raised his bushy brows very high. “His grandfather, lest we forget, was an infamous bloody traitor!”

“I will not see a man condemned for the actions of his grandfather!” snapped Orso, whose own grandfathers had enjoyed mixed reputations, to say the least. “Leo dan Brock risked his life fighting a duel on my behalf!”

“The job of your Closed Council,” said Glokta, “is to anticipate threats to Your Majesty before they become threats.”

“After may be too late,” threw in Bayaz.

“People are… discomfited by the death of your father,” said Gorodets. “So young. So unexpected.”

“Young. Unexpected.”

“And you, Your Majesty, are—”

“Despised?” offered Orso.

Gorodets gave an indulgent smile. “Untried. At times like this, people yearn for stability.”

“Indeed. It would without doubt be a very fine thing if Your Majesty were…” Lord Hoff cleared his throat. “To marry?”

Orso closed his eyes and pressed finger and thumb against them. “Must we?” Marriage was the last thing he wanted to discuss. He still had Savine’s note in a drawer beside his bed. Still looked at that brutal little line every evening, as one might pick at a scab. My answer must be no. I would ask you not to contact me again. Ever.

Hoff cleared his throat once more. “A new king always finds himself in an uncertain position.”

“A king with no heir, doubly so,” said Glokta.

“The absence of clear succession gives a troubling impression of impermanence,” observed Matstringer.

“Perhaps with the help of Her Majesty your mother, I might draw up a list of eligible ladies, both at home and abroad?” Hoff cleared his throat yet a third time. “A new list… that is.”

“By all means,” growled Orso, pronouncing each word with cutting precision.

“Then there is Fedor dan Wetterlant,” murmured the high justice.

Glokta’s permanent grimace became even further contorted. “I hoped we might settle that matter without bothering His Majesty.”

“I’m bothered now,” snapped Orso. “Fedor dan Wetterlant… didn’t I play cards with him once?”

“He lived in Adua before inheriting the family estate. His reputation here was…”

“Almost as bad as mine?” Orso remembered the man. Soft face but hard eyes. Smiled too much. Just like Lord Hoff, who was even now breaking out a particularly unctuous example.

“I was going to say abominable, Your Majesty. He stands accused of serious crimes.”

“He raped a laundry woman,” said Glokta, “with the assistance of his groundskeeper. When her husband demanded justice, Wetterlant murdered the man, again with the groundskeeper’s assistance. In a tavern. In full view of seventeen witnesses.” The emotionless quality of the Arch Lector’s grating voice only served to sicken Orso even more. “Then he had a drink. The groundskeeper poured, I believe.”

“Bloody hell,” whispered Orso.

“Those are the accusations,” said Matstringer.

“Even Wetterlant scarcely disputes them,” said Glokta.

“His mother does,” observed Gorodets.

There was a chorus of groans. “Lady Wetterlant, by the Fates, what a battleaxe.”

“Absolute. Harridan.”

“Well, I’m no admirer of hangings,” said Orso, “but I’ve seen men hanged for far less.”

“The groundskeeper already has been,” said Glokta.

“Shame,” grunted Brint with heavy irony, “he sounded like a real charmer.”

“But Wetterlant has asked for the king’s justice,” said Bruckel.

“His mother has demanded it!”

“And since he has a seat on the Open Council—”

“Not that his arse has ever touched it.”

“—he has the right to be tried before his peers. With Your Majesty as the judge. We cannot refuse.”

“But we can delay,” said Glokta. “The Open Council may not excel at much, but in delay it leads the world.”

“Postpone. Defer. Adjourn. I can wrap him up. In form and procedure. Until he dies in prison.” And the high justice smiled as though that was the ideal solution.

“We just deny him a hearing?” Orso was almost as disgusted by that option as by the crime itself.

“Of course not,” said Bruckel.

“No, no,” said Gorodets. “We would not deny him anything.”

“We’d simply never give him anything,” said Glokta.

Rucksted nodded. “I hardly think Fedor dan bloody Wetterlant or his bloody mother should be allowed to hold a dagger to the throat of the state simply because he can’t control himself.”

“He could at least lose control of himself in the absence of seventeen witnesses,” observed Gorodets, and there was some light laughter.

“So it’s not the rape or the murder we object to,” asked Orso, “but his being caught doing it?”

Hoff peered at the other councillors, as though wondering whether anyone might disagree. “Well…”

“Why should I not just hear the case, and judge it on its merits, and settle it one way or another?”

Glokta’s grimace twisted still further. “Your Majesty cannot judge the case without being seen to take sides.” The old men nodded, grunted, shifted unhappily in their uncomfortable chairs. “Find Wetterlant innocent, it will be nepotism, and favouritism, and will strengthen the hand of those traitors like the Breakers who would turn the common folk against you.”

“But find Wetterlant guilty…” Gorodets tugged unhappily at his beard and the old men grumbled more dismay. “The nobles would see it as an affront, as an attack, as a betrayal. It would embolden those who oppose you in the Open Council at a time when we are trying to ensure a smooth succession.”

“It seems sometimes,” snapped Orso, rubbing at those sore spots above his temples, “that every decision I make in this chamber is between two equally bad outcomes, with the best option to make no decision at all!”

Hoff glanced about the table again. “Well…”

“It is always a bad idea,” said the First of the Magi, “for a king to choose sides.”

Everyone nodded as though they had been treated to the most profound statement of all time. It was a wonder they did not rise and give a standing ovation. Orso was left in no doubt at which end of the table the power in the White Chamber truly lay. He remembered the look on his father’s face as Bayaz spoke. The fear. He made one more effort to claw his way towards his best guess at the right thing.

“Justice should be done. Shouldn’t it? Justice must be seen to be done. Surely! Otherwise… well… it’s not justice at all. Is it?”

High Justice Bruckel bared his teeth as if in physical pain. “At this level. Your Majesty. Such concepts become… fluid. Justice cannot be stiff like iron, but… more of a jelly. It must mould itself. About the greater concerns.”

“But… surely at this level, at the highest level, is where justice must be at its most firm. There must be a moral bedrock! It cannot all be… expediency?”

Exasperated, Hoff looked towards the foot of the table. “Lord Bayaz, perhaps you might…”

The First of the Magi gave a weary sigh as he sat forward, hands clasped, regarding Orso from beneath heavy lids. The sigh of a veteran schoolmaster, called on once again to explain the basics to this year’s harvest of dunces.

“Your Majesty, we are not here to set right all the world’s wrongs.”

Orso stared back at him. “What are we here for, then?”

Bayaz neither smiled nor frowned. “To ensure that we benefit from them.”

Superior Lorsen lowered the letter, frowning at Vick over the rims of his eye-lenses. He looked like a man who had not smiled in some time. Perhaps ever.

“His Eminence the Arch Lector writes you a glowing report. He tells me you were instrumental in ending the uprising at Valbeck. He feels I might need your help.” Lorsen turned his frown on Tallow, standing awkwardly in the corner, as if the idea of his being helpful with anything was an affront to reason. Vick still wasn’t sure why she’d brought him. Perhaps because she had no one else to bring.

“Not need my help, Superior,” she said. No bear, badger or wasp was more territorial than a Superior of the Inquisition, after all. “But I don’t have to tell you how damaging it would be, financially, politically, diplomatically… if Westport voted to leave the Union.”

“No,” said Lorsen crisply. “You do not.” As Superior of Westport, he’d be looking for a job.

“Which is why His Eminence felt you could perhaps use my help.”

Lorsen set down the letter, adjusted its position on his desk and stood. “Forgive me if I am dubious, Inquisitor, but performing surgery upon the politics of one of the world’s greatest cities is not quite the same as smashing up a strike.” And he opened the door onto the high gallery.

“The threats are worse and the bribes better,” said Vick as she followed him through, Tallow shuffling behind, “but otherwise I imagine there are similarities.”

“Then may I present to you our unruly workers: the Aldermen of Westport.” And Lorsen stepped to the balustrade and gestured down below.

There, on the floor of Westport’s cavernous Hall of Assembly, tiled with semi-precious stones in geometric patterns, the leadership of the city was debating the great question of leaving the Union. Some Aldermen stood, shaking fists or brandishing papers. Others sat, glumly watching or with heads in hands. Others bellowed over each other in at least five languages, the ringing echoes making it impossible to tell who was speaking, let alone what was being said. Others murmured to colleagues or yawned, scratched, stretched, gazed into space. A group of five or six had paused for tea in a distant corner. Men of every shape, size, colour and culture. A cross section through the madly diverse population of the city they called the Crossroads of the World, wedged onto a narrow scrap of thirsty land between Styria and the South, between the Union and the Thousand Isles.

“Two hundred and thirteen of them, at the current count, and each with a vote.” Lorsen pronounced the word with evident distaste. “When it comes to arguing, the citizens of Westport are celebrated throughout the world, and this is where their most dauntless arguers stage their most intractable arguments.” The Superior peered towards a great clock on the far side of the gallery. “They’ve been at it for seven hours already today.”

Vick was not surprised. There was a stickiness to the air from all the breath they’d wasted. The Fates knew she was finding Westport more than hot enough, even in spring, but she had been told that in summer, after particularly intense sessions, it could sometimes rain inside the dome. A sort of spitty drizzling back of all their high-blown language onto the furious Aldermen below.

“Seems the opinions are somewhat entrenched down there.”

“I wish they were more so,” said Lorsen. “Thirty years ago, after we beat the Gurkish, you couldn’t have found five votes for leaving the Union. But the Styrian faction has gained a great deal of ground lately. The wars. The debts. The uprising in Valbeck. The death of King Jezal. And his son is, shall we say, not yet taken seriously on the international stage. Without mincing words—”

“Our prestige is in the night pot,” Vick finished for him.

“We joined the Union because of their military might!” A truly mighty voice boomed out, finally cutting through the hubbub. The speaker was thickset, dark-skinned and shaven-headed with strangely gentle gestures. “Because the Empire of Gurkhul threatened us from the south and we needed strong allies to deter them. But membership has cost us dear! Millions of scales in treasure and the price forever rises!”

Agreement floated up to the gallery in an echoing murmur.

“Who’s the man with all the voice?” asked Vick.

“Solumeo Shudra,” said Lorsen, sourly. “The leader of the pro-Styrian faction and a royal thorn in my arse. Half-Sipanese, half-Kadiri. A fitting emblem for this cultural melting pot.”

Vick knew all this, of course. She made a great deal of effort to go into every job well informed. But she preferred to keep her knowledge to herself whenever possible, and let others imagine themselves the great experts.

“During the forty years since we joined the Union, the world has changed beyond all recognition!” bellowed Shudra. “The Empire of Gurkhul has crumbled, while Styria has turned from a patchwork of feuding city-states into one strong nation under one strong king. They have defeated the Union in not one, not two, but three wars! Wars waged for the vanity and ambitions of Queen Terez. Wars we were dragged into at vast expense in silver and blood.”

“He talks well,” said Tallow, softly.

“Very well,” said Vick. “He almost has me wanting to join Styria.”

“The Union is a waning power!” boomed Shudra. “While Styria is our natural ally. The hand of the Grand Duchess Monzcarro Murcatto is extended to us in friendship. We should seize it while we still can. My friends, I urge you all to vote with me to leave the Union!”

Loud boos, but even louder cheers. Lorsen shook his head in disgust. “If this were Adua, we could march in there, drag him from his seat, force a confession and ship him off to Angland on the next tide.”

“But we’re a long way from Adua,” murmured Vick.

“Both sides worry that an open display of force might turn the majority against them, but things will change as we move towards the vote. The positions are hardening. The middle ground is shrinking. Murcatto’s Minister of Whispers, Shylo Vitari, is mounting an all-encompassing campaign of bribery and threats, blackmail and coercion, while printed sheets are flung from the rooftops and painted slogans spring up faster than we can scrub them off.”

“I’m told Casamir dan Shenkt is in Westport,” said Vick. “That Murcatto has paid him one hundred thousand scales to shift the balance. By any means necessary.”

“I had heard… the rumours.”

She got the sense that Lorsen had heard the same rumours she had, delivered in breathless whispers with a great deal of lurid detail. That Shenkt’s skills went beyond the mortal and touched the magical. That he was a sorcerer who had damned himself by eating the flesh of men. Here in Westport, where calls to prayer echoed hourly over the city and cut-price prophets declaimed on every corner, such ideas were somehow harder to dismiss.

“Might I lend you a few Practicals?” Lorsen peered at Tallow. To be fair, the lad didn’t look as if he could stand up to a stiff breeze, let alone a flesh-eating magician. “If Styria’s most famous assassin is really on the prowl, we need you well protected.”

“An armed escort would send the wrong message.” And would do no good anyway, if those rumours really were true. “I was sent to persuade, not intimidate.”

Lorsen was less than convinced. “Really?”

“That’s how it has to look.”

“Little would look worse than the untimely death of His Eminence’s representative.”

“I don’t intend to rush at the grave, believe me.”

“Few do. The grave swallows us all regardless.”

“What are your plans, Superior?”

Lorsen took a weary breath. “I have my hands full protecting our own Aldermen. The ballots are cast in nineteen days, and we cannot afford to lose a single vote.”

“Taking away some of theirs would help.”

“Providing it is done subtly. If their people turn up dead, it is sure to harden feelings against us. Things are finely balanced.” Lorsen clenched his fists on the railing as Solumeo Shudra boomed out another speech lauding the benefits of Styria’s welcoming embrace. “And Shudra has proved persuasive. He is well loved here. I am warning you, Inquisitor—don’t go after him.”

“With all due respect, the Arch Lector has sent me to do the things you can’t. I only take orders from him.”

Lorsen gave her a long, cold stare. Probably it was a look that froze the blood in people used to Westport’s warm climate, but Vick had worked down a half-flooded mine in an Angland winter. It took a lot to make her shiver. “Then I am asking you.” He pronounced each word precisely. “Don’t go after him.”

Below them, Shudra had finished his latest thunderous contribution to noisy applause from the men around him and even noisier booing from the other side. Fists were shaken, papers were flung, insults were grumbled. Nineteen more days of this pantomime, with Shylo Vitari trying everything to twist the outcome. Who knew how that would turn out?

“His Eminence wants me to keep Westport in the Union.” She headed for the door with Tallow at her heels. “At any cost.”

“Welcome, one and all, to this fifteenth biannual meeting of Adua’s Solar Society.”

Curnsbick, resplendent in a waistcoat embroidered with silver flowers, held up his broad hands for silence, though the applause was muted. The members used to raise the roof of the theatre. Savine remembered it well.

“With thanks to our distinguished patrons—the Lady Ardee and her daughter Lady Savine dan Glokta.” Curnsbick gave his usual showman’s flourish towards the box where Savine sat, but the clapping now was yet more subdued. Did she even hear a few tattletale whispers below? She’s not all she was, you know. Not one half of what she was…

“Ungrateful bastards,” she hissed through her fixed smile. Could it only have been a few months since they were soiling their drawers at the mention of her name?

“To say that it has been a difficult year…” Curnsbick frowned down at his notes as though they made sad reading. “Hardly does justice to the troubles we have faced.”

“You’re fucking right there.” Savine dipped behind her fan to sniff up a pinch of pearl dust. Just to lift her out of the bog. Just to keep some wind in the sails.

“A war in the North. Ongoing troubles in Styria. And the death of His August Majesty King Jezal the First. Too young. Far too young.” Curnsbick’s voice cracked a little. “The great family of our nation has lost its great father.”

Savine flinched at the word, had to give her own eye the slightest dab with the tip of her little finger, though no doubt any tears were for her own troubles rather than a father she had hardly known and certainly not respected. All tears are for oneself, in the end.

“Then the terrible events in Valbeck.” A kind of sorry grumble around the theatre, a stirring below as every head was shaken. “Assets ruined. Colleagues lost. Manufactories that were the wonder of the world left in ruins.” Curnsbick struck his lectern a blow. “But already new industry rises from the ashes! Modern housing on the ruins of the slums! Greater mills with more efficient machinery and more orderly workers!”

Savine tried not to think of the children in her mill in Valbeck, before it was destroyed. The bunk beds wedged in among the machines. The stifling heat. The deafening noise. The choking dust. But so awfully orderly. So terribly efficient.

“Confidence has been struck,” lamented Curnsbick. “Markets are in turmoil. But from chaos, opportunity can come.” He gave his lectern another blow. “Opportunity must be made to come. His August Majesty King Orso will lead us into a new age. Progress cannot stop! Will not be permitted to stop! For the benefit of all, we of the Solar Society will fight tirelessly to drag the Union from the tomb of ignorance and into the sunny uplands of enlightenment!”

Loud applause this time, and in the audience below, men struggled to their feet.

“Hear! Hear!” someone brayed.

“Progress!” blurted another.

“As inspiring as any sermon in the Great Temple of Shaffa,” murmured Zuri.

“If I didn’t know better, I’d say Curnsbick has taken

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...