- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

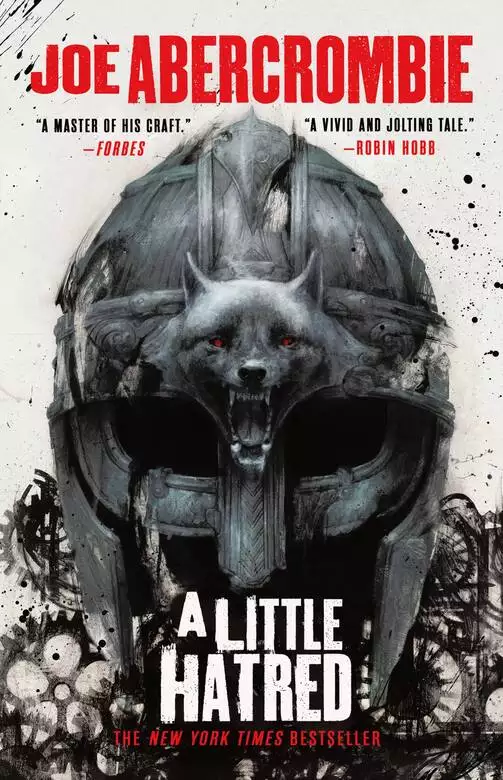

From New York Times best-selling author Joe Abercrombie comes the first audiobook in a blockbuster fantasy trilogy where the age of the machine dawns, but the age of magic refuses to die.

The chimneys of industry rise over Adua, and the world seethes with new opportunities. But old scores run deep as ever.

On the blood-soaked borders of Angland, Leo dan Brock struggles to win fame on the battlefield, and defeat the marauding armies of Stour Nightfall. He hopes for help from the crown. But King Jezal's son, the feckless Prince Orso, is a man who specializes in disappointments.

Savine dan Glokta — socialite, investor, and daughter of the most feared man in the Union — plans to claw her way to the top of the slag-heap of society by any means necessary. But the slums boil over with a rage that all the money in the world cannot control.

The age of the machine dawns, but the age of magic refuses to die. With the help of the mad hillwoman Isern-i-Phail, Rikke struggles to control the blessing, or the curse, of the Long Eye. Glimpsing the future is one thing, but with the guiding hand of the First of the Magi still pulling the strings, changing it will be quite another...

Release date: September 17, 2019

Publisher: Hachette Audio

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Little Hatred

Joe Abercrombie

She prised one eye open. A slit of stabbing, sickening brightness.

“Come back.”

She pushed the spit-wet dowel out of her mouth with her tongue and croaked the one word she could think of. “Fuck.”

“There’s my girl!” Isern squatted beside her, necklace of runes and finger bones dangling, grinning that twisted grin that showed the hole in her teeth and offering no help at all. “What did you see?”

Rikke heaved one hand up to grip her head. Felt like if she didn’t hold her skull together, it’d burst. Shapes still fizzed on the inside of her lids, like the glowing smears when you’ve looked at the sun.

“I saw folk falling from a high tower. Dozens of ’em.” She winced at the thought of them hitting the ground. “I saw folk hanged. Rows of ’em.” Her gut cramped at the memory of swinging bodies, dangling feet. “I saw… a battle, maybe? Below a red hill.”

Isern sniffed. “This is the North. Takes no magic to see a battle coming. What else?”

“I saw Uffrith burning.” Rikke could almost smell the smoke still. She pressed her hand to her left eye. Felt hot. Burning hot.

“What else?”

“I saw a wolf eat the sun. Then a lion ate the wolf. Then a lamb ate the lion. Then an owl ate the lamb.”

“Must’ve been a real monster of an owl.”

“Or a tiny little lamb, I guess? What does it mean?”

Isern held a fingertip to her scarred lips, the way she did when she was on the verge of deep pronouncements. “I’ve no frigging clue. Mayhap the turning of time’s wheel shall unlock the secrets of these visions.”

Rikke spat, but her mouth still tasted like despair. “So… wait and see.”

“Eleven times out of twelve, that’s the best course.” Isern scratched at the hollow above her collarbone and winked. “But if I said it that way, no one would reckon me a deep thinker.”

“Well, I can unveil two secrets right away.” Rikke groaned as she pushed herself up onto one elbow. “My head hurts and I shat myself.”

“That second one’s no secret, anyone with a nose is party to it.”

“Shitty Rikke, they’ll call me.” She wrinkled her nose as she shifted. “And not for the first time.”

“Your problem is in caring what they call you.”

“My problem is I’m cursed with fits.”

Isern tapped under her left eye. “You say cursed with fits, I say blessed with the Long Eye.”

“Huh.” Rikke rolled onto her knees and her stomach kept on rolling and tickled her throat with sick. By the dead, she felt sore and squeezed out. Twice the pain of a night at the ale cup and none of the sweet memories. “Doesn’t feel like much of a blessing to me,” she muttered, once she’d risked a little burp and fought her guts to a draw.

“There are few blessings without a curse hidden inside, nor curses without a whiff of blessing.” Isern carved a little piece of chagga from a dried-out chunk. “Like most things, it’s a matter of how you look at it.”

“Very profound.”

“As always.”

“Maybe someone whose head hurt less would enjoy your wisdom more.”

Isern licked her fingertips, rolled the chagga into a pellet and offered it to Rikke. “I am a bottomless well of revelation but cannot force the ignorant to drink. Now get your trousers off.” She barked out that savage laugh of hers. “Words many a man has longed to hear me say.”

Rikke sat with her back to one of the snow-capped standing stones, eyes narrowed as the sun flashed through the dripping branches, the fur cloak her father gave her hugged around her shoulders and the raw wind wafting around her bare arse. She chewed chagga and chased the itches that danced all over her with black-edged fingernails, trying to calm her mangled nerves and shake off the memories of that tower, and those hanged, and of Uffrith burning.

“Visions,” she muttered. “A curse for sure.”

Isern squelched up the bank with Rikke’s dripping trousers. “Clean as new snow! Your only stench now shall be of youth and disappointment.”

“You’re one to talk of stenches, Isern-i-Phail.”

Isern raised her sinewy, tattooed arm, sniffed at her pit and gave a satisfied sigh. “I’ve a goodly, earthy, womanly savour of a kind much loved by the moon. If you’re rattled by an odour, you picked the wrong companion.”

Rikke spat chagga juice but messed it up and got most of it down her chin. “If you think I picked any part of this, you’re mad.”

“They said the same thing about my da.”

“He was mad as a sack of owls, you’re always saying so!”

“Aye, well, one person’s mad is another’s remarkable. Need I observe you’re a long leap from ordinary yourself? You kicked so hard this time you nearly kicked your boots off. Might have to rope you in future, make sure you don’t crack your nut and end up a drooler like my brother Brait. At least he can keep his shit in, mind you.”

“My thanks for that.”

“No bother.” Isern made a little diamond from her fingers and squinted through it at the sun. “Past time we were on our way. High deeds are being done today. Or maybe low ones.” And she dropped the trousers in Rikke’s lap. “Best dress yourself.”

“What, wet? They’ll chafe.”

“Chafe?” Isern snorted. “That’s the limit o’ your worries?”

“My head still aches so bad I can feel it in my teeth.” Rikke wanted to shout but knew it’d hurt too much, so she had to whine it soft instead. “I need no more small discomforts.”

“Life is small discomforts, girl! They’re how you know you are alive.” And Isern hacked that laugh out again, slapped happily at Rikke’s shoulder and sent her stumbling sideways. “You can walk with your plump white arse hanging out if that’s your pleasure, but you’ll be walking one way or the other.”

“A curse,” grumbled Rikke as she wriggled into her clammy trousers. “Definitely a curse.”

“So… you really think I’ve got the Long Eye?”

Isern strode on through the woods with that loping gait that, however fast Rikke walked, always left her an uncomfortable half-step behind. “You really think I’d be pissing my efforts away on you otherwise?”

Rikke sighed. “Guess not. Just, in the songs, it’s a thing witches and magi and deep-wise folk used to see into the fog of what comes. Not a thing that makes idiots fall down and shit themselves.”

“In case you never noticed, bards have a habit of dressing things up. There is a fine living, d’you see, in songs about deep-wise witches, but in shitty idiots, less.”

Rikke sadly conceded the truth of that.

“And proving you have the Long Eye is no simple matter. You cannot force it open. You must coax it.” And Isern tickled Rikke under the chin and made her jerk away. “Take it up to the sacred places where the old stones stand so the moon might shine full upon it. But it’ll see what it sees when it chooses, even so.”

“Uffrith on fire, though?” Rikke was feeling a weight of worry now they were down from the High Places and getting close to home. The dead knew she hadn’t always been happy in Uffrith, but she’d no wish to see it in flames. “How’s that meant to happen?”

“Carelessness with a cook-fire would do it.” Isern’s eyes slid sideways. “Though up here in the North, I’d say war’s a more likely cause of cities aflame.”

“War?”

“It’s when a fight gets so big almost no one comes out of it well.”

“I know what it bloody is.” Rikke had a spot of fear growing at the nape of her neck which she couldn’t shrug off however much she wriggled her shoulders. “But there’s been peace in the North all my lifetime.”

“My da used to say times of peace are when the wise prepare for violence.”

“Your da was mad as a bootful of dung.”

“And what does your da say? Few men so sane as the Dogman.”

Rikke wriggled her shoulders one more time, but nothing helped. “He says hope for the best and prepare for the worst.”

“Sound advice, say I.”

“But he lived through some black times. Always fighting. Against Bethod. Against Black Dow. Things were different then.”

Isern snorted. “No, they weren’t. I was there when your father fought Bethod, up in the High Places with the Bloody-Nine beside him.”

Rikke blinked at her. “You can’t have been ten years old.”

“Old enough to kill a man.”

“What?”

“Used to carry my da’s hammer, ’cause the smallest should take the heaviest load, but that day he was fighting with the hammer so I had his spear. This very one.” Its butt tapped the rhythm of their walking on the path. “My da knocked a man down, and he was trying to get up, and I stabbed him right up the arse.”

“With that spear?” Rikke had come to think of it as just a stick Isern carried. A stick that happened to have a deerskin cover over one end. She didn’t like thinking there was a blade under there. Especially not one that had been up some poor bastard’s arse.

“Well, it’s had a few new shafts since then, but—” Isern stopped dead, tattooed hand raised and eyes narrowed. All Rikke could hear was whispering branches, the tap, tap of drips from the melting snow, the tweet, tweet of birds in the budding trees.

Rikke leaned towards her. “What’s the—”

“Nock a shaft to your bow and keep ’em talking,” whispered Isern.

“Who?”

“Failing that, show ’em your teeth. You’re blessed with fine teeth.” And she darted off the road and into the trees.

“My teeth?” hissed Rikke, but Isern’s flitting shadow had already vanished in the brambles.

That was when she heard a man’s voice. “Sure this is the way?”

She’d had her bow over her shoulder hoping for a deer and now she shrugged it off, fumbled out an arrow and nearly dropped it, managed to get it nocked in spite of a flurry of nervy twitches up her arm.

“We was told check the woods.” A deeper, harder, scarier voice. “Do these look like woods?”

She had a sudden panic it might just be a squirrel arrow, checked it was a proper broadhead.

“Forest, I guess.”

Laughter. “What’s the bloody difference?”

An old man came around the bend in the road. He’d a staff in his hand, and he lowered it, metal gleaming in the dappled light, and Rikke realised it wasn’t a staff but a spear, and she felt the worry spread out from that spot on her neck to the roots of her hair.

There were three of them. The old one had a sorry look like none of this was his idea. Next came a nervous lad with a shield and a short axe. Finally, there was a big man with a heavy beard and a heavier frown. Rikke didn’t like the look of him at all.

Her father always said don’t point arrows at folk unless you mean to see ’em dead, so she drew her bow halfway and pointed it at the road.

“Best hold still,” she said.

The old one stared at her. “Girl, you have a ring through your nose.”

“I am aware.” And Rikke stuck her tongue out and touched the tip to it. “It keeps me tethered.”

“You might wander off?”

“My thoughts might.”

“Is it gold?” asked the lad.

“Copper,” she lied, since gold is apt to turn unpleasant meetings into deadly ones.

“And the paint?”

“The mark of the cross is a goodly mark much loved by the moon. The Long Eye is the left eye and the cross will keep its sight true through the fog of what comes.” She turned her head and spat chagga juice without taking her eyes off them, then added, “Maybe,” since she wasn’t sure the cross had done a thing but get smeared on her pillow when she forgot to wipe it off of an evening.

She wasn’t the only doubter. “You mad?” growled the big man.

Rikke sighed. Far from the first time she’d fielded that question. “One person’s mad is another’s remarkable.”

“Be a fine thing if you were to put that bow down,” said the old one.

“I like it where it is.” Though she definitely didn’t, it was getting all sticky in her hand, shoulder aching from the effort of holding it half-drawn and a twitch in her neck starting up that she worried might jerk the string loose.

Seemed the lad trusted her to hold it even less than she did, peering at her over the rim of his shield. It was only then she noticed what was painted on it.

“You’ve a wolf on your shield,” she said.

“Stour Nightfall’s mark,” growled the big man, with a hint of pride, and Rikke saw he had a wolf on his shield, too, though his was scuffed almost back to the wood.

“You’re Nightfall’s men?” The fear was spreading all the way into her guts now. “What you doing down here?”

“Putting an end to the Dogman and his arse-lickers, and bringing Uffrith back into the North where it belongs.”

Rikke’s knuckles whitened around her bow, fear turning to anger. “You’re fucking not!”

“Already happening.” The old man shrugged. “Only question for you is whether you’ll be raised up with the winners or put in the mud with the losers.”

“Nightfall’s the greatest warrior since the Bloody-Nine!” piped up the young one. “He’s going to take back Angland and drive the Union out o’ the North!”

“The Union?” And Rikke looked down at the wolf’s head badly daubed on his badly made shield. “A wolf ate the sun,” she whispered.

“She is bloody mad.” The big one stepped forwards. “Now drop the—” And he made this long wheeze, and his shirt stuck out, a glint of metal showing.

“Oh,” he said, dropping to his knees.

The lad turned around.

Rikke’s arrow stuck into his back, just under his shoulder blade.

Her turn to say, “Oh,” not sure whether she’d meant to let go the string or not.

A flash of metal and the old man’s head jolted, the blade of Isern’s spear catching him in the throat. He dropped his own spear, grabbed for her with clumsy fingers.

“Shush.” Isern slapped his hand away and ripped the blade free in a black gout. He wriggled on the ground, fiddling with the great wound in his neck as if he might stop it splurting. He was trying to say something, but fast as he could spit the blood out, his mouth filled up again. Then he stopped moving.

“You killed ’em.” Rikke felt all hot. There were some red speckles on her hand. The big one was lying on his face, shirt soaked dark.

“You killed this one,” said Isern. The lad knelt there, making these squeaky little gasps as he tried to reach around his back to the arrow shaft, though what he’d do if he got his fingertips to it, Rikke had no idea. Probably he’d no idea, either. Isern was the only one thinking clearly right then. She leaned down and calmly plucked the knife from the lad’s belt. “Was hoping to set him a question or two, but he’ll be giving no answers with that shaft in his lung.”

As if to prove the point, he coughed some blood into his hand, and stared over it at Rikke. He looked a bit offended, like she’d said something hurtful.

“Still, no one ever gets things all their own way.” Rikke jumped at the crack as Isern rammed the lad’s knife into the crown of his head. His eyes rolled up and his leg kicked and his back arched. Just like hers did, maybe, when a fit came upon her.

The hairs were standing on Rikke’s arms as he slumped down limp. She never saw a man killed before. All happened so fast she didn’t know how she ought to feel about it.

“They didn’t seem so bad,” she said.

“For a girl struggling to penetrate the mists of the future, you don’t half miss what’s right in front of you.” Isern was already rooting through the old man’s pockets, point of her tongue wedged in the hole in her teeth. “If you wait till they seem bad, you’ve waited way too long.”

“Could’ve given ’em a chance.”

“To what? Put you in the mud? Or drag you off to Stour Nightfall? Chafing would’ve been the least of your worries then, that boy’s got a bastard of a reputation.” She caught the old man’s leg and dragged him from the path into the undergrowth, tossed his spear after. “Or were we going to invite ’em dancing through the woods with us, and all wear flowers in our hair and win ’em over to our side with my pretty words and your pretty smile?”

Rikke spat some chagga juice and wiped her chin, watching the blood work its way through the dirt about the lad’s nailed head. “Doubt my smile’s up to the task and I’m damn sure your words ain’t.”

“Then killing ’em was all o’ the one choices we had, eh? Your problem is you’re all heart.” And she stabbed Rikke in the tit with one bony finger.

“Ow!” Rikke took a step away, holding her arms across her chest. “That hurts, you know!”

“You’re all heart all over, so you feel every sting and buffet. You must make of your heart a stone.” And Isern thumped her ribs with a fist, the finger bones around her neck rattling. “Ruthlessness is a quality much loved o’ the moon.” As if to prove the point, she bent down and heaved the dead lad into the bushes. “A leader must be hard, so others don’t have to be.”

“Leader o’ what?” muttered Rikke, rubbing at her sore tit. And that was when she caught a whiff of smoke, just like in her dream. As if it was a tugging she couldn’t resist, she set off down the path.

“Oy!” called Isern around a stick of dry meat she’d rooted out of the big one’s pouch. “I need help dragging this big bastard!”

“No,” whispered Rikke, the smell of fire getting stronger and her worry getting stronger with it. “No, no, no.”

She burst from the trees and into cold daylight, took a couple more wobbling steps and stopped, bow dangling from her limp hand.

The morning mist was long faded and she could see all the way across the patchwork of new-planted fields to Uffrith, wedged in against the grey sea behind its grey wall. Where her father’s old hall stood with the scraggy garden out the back. Safe, boring Uffrith, where she’d been born and raised. Only it was burning, just the way she’d seen it, and a great column of dark smoke rolled up and smudged the sky, drifting out over the restless sea.

“By the dead,” she croaked.

Isern wandered from the trees with her spear across her shoulders and a great smile across her face. “You know what this means?”

“War?” whispered Rikke, horrified.

“Aye, that.” Isern waved it away like it was a trifle. “But more to the matter, I was right!” And she clapped Rikke on the shoulder so hard she near knocked her down. “You do have the Long Eye!”

In battle, Leo’s father used to say, a man discovers who he truly is.

The Northmen were already turning to run as his horse crashed into them with a thrilling jolt.

He smashed one across the back of the helmet with the full force of the charge and ripped his head half off.

He snarled as he swung to the other side. A glimpse of a gawping face before his axe split it open, blood spraying in black streaks.

Other riders tore into the Northmen, tossing them like broken dolls. He saw one horse spitted through the head with a spear. The rider turned a somersault as he was flung from the saddle.

A lance shattered, a shard flying into Leo’s helmet with an echoing clang as he wrenched away. The world was a flickering slit of twisted faces, glinting steel, heaving bodies, half seen through the slot in his visor. Screams of men and mounts and metal mashed into one thought-crushing din.

A horse swerved in front of him. Riderless, stirrups flapping. Ritter’s horse. He could tell by the yellow saddlecloth. A spear stabbed at him, jolting the shield on his arm, rocking him in his saddle. The point screeched down his armoured thigh.

He gripped the reins in his shield-hand as his mount bucked and snorted, face locked in an aching smile, flailing wildly with his axe on one side, then the other. He beat mindlessly at a shield with a black wolf painted on it, kicked at a man and sent him staggering back, then Barniva’s sword flashed as it took his arm off.

He saw Whitewater Jin swinging his mace, red hair tangled across gritted teeth. Just beyond him, Antaup was shrieking something as he tried to twist his spear free of bloody mail. Glaward wrestled with a Carl, both without weapons, all tangled with their reins. Leo hacked at the Northman and smashed his elbow back the wrong way, hacked again and sent him flopping into the mud.

He pointed at Stour Nightfall’s standard with his axe, black wolf streaming in the wind. He howled, roared, throat hoarse. No one could hear him with his visor down. No one could’ve heard him if it had been up. He hardly knew what he was saying. He flailed furiously at the milling bodies instead.

Someone clutched at his leg. Curly hair. Freckles. Looked bloody terrified. Everyone did. Didn’t seem to have a weapon. Maybe surrendering. Leo smashed Freckles on the top of the head with the rim of his shield, gave his horse the spurs and trampled him into the mud.

This was no place for good intentions. No place for tedious subtleties or boring counter-arguments. None of his mother’s carping on patience and caution. Everything was beautifully simple.

In battle, a man discovers who he truly is, and Leo was the hero he’d always dreamed of being.

He swung again but his axe felt strange. The blade had flown off, left him holding a bloody stick. He dropped it, dragged out his battle steel, buzzing fingers clumsy in his gauntlet, hilt greasy from the thickening rain. He realised the man he’d been hitting was dead. He’d fallen against the fence, so it looked as if he was standing but there was black pulp hanging out of his broken skull, so that was that.

The Northmen were crumbling. Running, squealing, being hacked down from behind, and Leo herded them towards their standard. Three riders had a whole crowd of them hemmed into a gateway, Barniva in their midst, scarred face flecked with blood as he chopped away with his heavy sword.

The standard-bearer was a huge man with desperate eyes and blood in his beard, still holding high the flag of the black wolf. Leo spurred right at him, blocked axe with shield, caught him with a sword-cut that screeched over his cheek guard and opened a great gash across his face, carved half his nose off. He tottered back and Whitewater Jin crushed the man’s helmet with his mace, blood squirting from under the rim. Leo kicked him over, tearing the standard from his limp hand as he fell. He thrust it up, laughing, gurgling, half-choking on his own spit then laughing again, his axe’s loop still stuck around his wrist so the broken haft clattered against his helmet.

Had they won? He stared around for more enemies. A few ragged figures bounded through the crops towards the distant trees. Running for their lives, weapons abandoned. That was all.

Leo ached all over: thighs from gripping his horse, shoulders from swinging his axe, hands from gripping the reins. The very soles of his feet throbbed from the effort. His chest heaved, breath booming in his helmet, damp, and hot, and tasting of salt. Might’ve bit his tongue somewhere. He fumbled with the buckle under his chin, finally tore the damn thing free. His skull burst with the noise, turned from fury to delight. The noise of victory.

He almost fell from his horse, clambered up onto the wall. Something was soft under his gauntleted hand. A Northman’s corpse, a broken spear sticking from his back. All he felt was giddy joy.

No corpses, no glory, after all. Might as well regret the peelings from a carrot. Someone was helping him up, giving him a steadying hand. Jurand. Always there when he needed him. Leo stood tall, the joyful faces of his men all turned towards him.

“The Young Lion!” roared Glaward, climbing up beside him and clapping a heavy hand on his shoulder, making him wobble. Jurand stretched out his arms to catch him, but he didn’t fall. “Leo dan Brock!” Soon they were all shouting his name, singing it like a prayer, chanting it like a magic word, stabbing their glittering weapons at the spitting sky.

“Leo! Leo! Leo!”

In battle, a man discovers who he truly is.

He felt drunk. He felt on fire. He felt like a king. He felt like a god. This was what he was made for!

“Victory!” he roared, shaking his bloody sword and the Northmen’s bloody standard.

By the dead, could there be anything better than this?

In the lady governor’s tent, they were fighting a different kind of war. A war of patient study and careful calculation, of weighed odds and furrowed brows, of lines of supply and an awful lot of maps. A kind of war Leo frankly hadn’t the patience for.

The glow of victory had been dampened by the stiffening rain on the long trudge up from the valley, doused further by the niggling pain from a dozen cuts and bruises, and was almost entirely smothered by the cool stare his mother gave him as Leo pushed through the flap with Jurand and Whitewater Jin at his back.

She was in the midst of talking to a knight herald. Ridiculously tall, he had to stoop respectfully to attend to her.

“… please tell His Majesty we are doing everything to check the Northmen’s advance, but Uffrith is lost and we are giving ground. They struck with overwhelming force at three points and we are still gathering our troops. Ask him… no, beg him to send reinforcements.”

“I will, my Lady Governor.” The knight herald nodded to Leo as he passed. “My congratulations on your victory, Lord Brock.”

“We don’t need the king’s bloody help!” snapped Leo as soon as the flap dropped. “We can beat Black Calder’s dogs!” His voice sounded oddly weak in the tent, deadened by wet cloth. It didn’t carry anywhere near so nicely as it had on the battlefield.

“Huh.” His mother planted her fists on the table and frowned down at her maps. By the dead, sometimes he thought she loved those maps more than him. “If we are to fight the king’s battles, we should expect the king’s help.”

“You should’ve seen them run!” Damn it, but Leo had been so sure of himself a few moments ago. He could charge a line of Carls and never falter, but a woman with a long neck and greying hair leached all the courage out of him. “They broke before we even got to them! We took a few dozen prisoners…” He glanced towards Jurand, but he was giving Leo that doubtful look now, the one he used when he didn’t approve, the one he’d given him before the charge. “And the farm’s back in our hands… and…”

His mother let him stammer into silence before she glanced at his friends. “My thanks, Jurand. I’m sure you did your best to talk him out of it. And you, Whitewater. My son couldn’t ask for better friends or I for braver warriors.”

Jin slapped a heavy hand down on Leo’s shoulder. “It was Leo who led the—”

“You can go.”

Jin scratched sheepishly at his beard, showing a lot less warrior’s mettle than he had down in the valley. Jurand gave Leo the slightest apologetic wince. “Of course, Lady Finree.” And they slunk from the tent, leaving Leo to fiddle weakly with the fringe of his captured standard.

His mother let the withering silence stretch a moment longer before she passed judgement. “You bloody fool.”

He’d known it was coming, but it still stung. “Because I actually fought?”

“Because of when you chose to fight, and how.”

“Great leaders go where the fight’s hottest!” But he knew he sounded like the heroes in the badly written storybooks he used to love.

“You know who else you find where the fight’s hottest?” asked his mother. “Dead men. We both know you’re not a fool, Leo. For whose benefit are you pretending to be one?” She shook her head wearily. “I should never have let your father send you to live with the Dogman. All you learned in Uffrith was rashness, bad songs and a childish admiration for murderers. I should have sent you to Adua instead. I doubt your singing would be any better but at least you might have learned some subtlety.”

“There’s a time for subtlety and a time for action!”

“There is never a time for recklessness, Leo. Or for vanity.”

“We bloody won!”

“Won what? A worthless farm in a worthless valley? That was little more than a scouting party, and now the enemy will guess our strength.” She gave a bitter snort as she turned back to her maps. “Or the lack of it.”

“I captured a standard.” It seemed a pitiful thing now he really looked at it, though, clumsily stitched, the pole closer to a branch than a flagstaff. How could he have thought Stour Nightfall himself might ride beneath it?

“We have plenty of flags,” said his mother. “It’s men to follow them we’re short of. Perhaps you could bring back a few regiments of those next time?”

“Damn it, Mother, I don’t know how to please you—”

“Listen to what you’re told. Learn from those who know better. Be brave, by all means, but don’t be rash. Above all, don’t get yourself bloody killed! You’ve always known exactly how to please me, Leo, but you choose to please yourself.”

“You can’t understand! You’re not…” He waved an impatient hand, failing, as always, to quite find the right words. “A man,” he finished lamely.

She raised one brow. “Had I been confused on that point, it was put beyond doubt when I pushed you out of my womb. Have you any notion how much you weighed as a baby? Spend two days shitting an anvil and we’ll talk again.”

“Bloody hell, Mother! I mean that men will look up to a certain kind of man, and—”

“Like your friend Ritter looked up to you?”

Leo was caught out by the memory of that riderless horse clattering past. He realised he hadn?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...