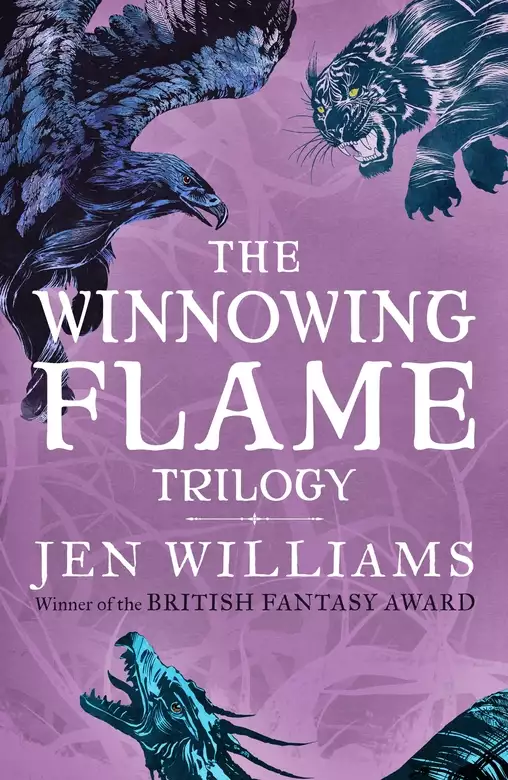

The Winnowing Flame Trilogy

Available in:

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Series info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From Book 1:

Jen Williams, acclaimed author of The Copper Cat trilogy, featuring THE COPPER PROMISE, THE IRON GHOST and THE SILVER TIDE, returns with the first in a blistering new trilogy. 'An original new voice in heroic fantasy' Adrian TchaikovskyThe great city of Ebora once glittered with gold. Now its streets are stalked by wolves. Tormalin the Oathless has no taste for sitting around waiting to die while the realm of his storied ancestors falls to pieces - talk about a guilt trip. Better to be amongst the living, where there are taverns full of women and wine.

When eccentric explorer, Lady Vincenza 'Vintage' de Grazon, offers him employment, he sees an easy way out. Even when they are joined by a fugitive witch with a tendency to set things on fire, the prospect of facing down monsters and retrieving ancient artefacts is preferable to the abomination he left behind.

But not everyone is willing to let the Eboran empire collapse, and the adventurers are quickly drawn into a tangled conspiracy of magic and war. For the Jure'lia are coming, and the Ninth Rain must fall...

Release date: December 1, 2022

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 960

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Winnowing Flame Trilogy

Jen Williams

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

About Jen Williams

Praise

Also by Jen Williams

The Ninth Rain Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Acknowledgements

The Bitter Twins Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Acknowledgements

The Poison Song Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Acknowledgements

‘Will we get into trouble?’

Hestillion took hold of the boy’s hand and gave it a quick squeeze. When he looked up at her, his eyes were wide and glassy – he was afraid. The few humans who came to Ebora generally were. She favoured him with a smile and they walked a little faster down the echoing corridor. To either side of them enormous oil paintings hung on the walls, dusty and grey. A few of them had been covered with sheets, like corpses.

‘Of course not, Louis. You are with me, aren’t you? I can go anywhere in the palace I like, and you are my friend.’

‘I’ve heard that people can go mad, just looking at it.’ He paused, as if sensing that he might have said something wrong. ‘Not Eborans, I mean. Other people, from outside.’

Hestillion smiled again, more genuinely this time. She had sensed this from the delegates’ dreams. Ygseril sat at the centre of their night wanderings, usually unseen but always there, his roots creeping in at the corners. They were all afraid of him: bad dreams conjured by thousands of years’ worth of the stories and rumours. Hestillion had kept herself carefully hidden while exploring their nightmares. Humans did not care for the Eboran art of dream-walking.

‘It is quite a startling sight, I promise you that, but it cannot harm you.’ In truth, the boy would already have seen Ygseril, at least partly. The tree-god’s great cloud of silvery branches burst up above the roof of the palace, and it was possible to see it from the Wall, and even the foothills of the mountains; or so she had been told. The boy and his father, the wine merchant, could hardly have missed it as they made their way into Ebora. They would have found themselves watching the tree-god as they rode their tough little mountain ponies down into the valley, wine sloshing rhythmically inside wooden casks. Hestillion had seen that in their dreams, too. ‘Here we are, look.’

At the end of the corridor was a set of elaborately carved double doors. Once, the phoenixes and dragons etched into the wood would have been painted gold, their eyes burning bright and every tooth and claw and talon picked out in mother-of-pearl, but it had all peeled off or been worn away, left as dusty and as sad as everything else in Ebora. Hestillion leaned her weight on one of the doors and it creaked slowly open, showering them in a light rain of dust. Inside was the cavernous Hall of Roots. She waited for Louis to gather himself.

‘I . . . oh, it’s . . .’ He reached up as if to take off his cap, then realised he had left it in his room. ‘My lady Hestillion, this is the biggest place I’ve ever seen!’

Hestillion nodded. She didn’t doubt that it was. The Hall of Roots sat at the centre of the palace, which itself sat in the centre of Ebora. The floor under their feet was pale green marble etched with gold – this, at least, had yet to be worn away – and above them the ceiling was a glittering lattice of crystal and finely spun lead, letting in the day’s weak sunshine. And bursting out of the marble was Ygseril himself; ancient grey-green bark, rippled and twisted, a curling confusion of roots that sprawled in every direction, and branches, high above them, reaching through the circular hole in the roof, empty of leaves. Little pieces of blue sky glittered there, cut into shards by the arms of Ygseril. The bark on the trunk of the tree was wrinkled and ridged, like the skin of a desiccated corpse. Which was, she supposed, entirely appropriate.

‘What do you think?’ she pressed. ‘What do you think of our god?’

Louis twisted his lips together, obviously trying to think of some answer that would please her. Hestillion held her impatience inside. Sometimes she felt like she could reach in and pluck the stuttering thoughts from the minds of these slow-witted visitors. Humans were just so uncomplicated.

‘It is very fine, Lady Hestillion,’ he said eventually. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it, not even in the deepest vine forests, and my father says that’s where the oldest trees in all of Sarn grow.’

‘Well, strictly speaking, he is not really a tree.’ Hestillion walked Louis across the marble floor, towards the place where the roots began. The boy’s leather boots made odd flat notes of his footsteps, while her silk slippers gave only the faintest whisper. ‘He is the heart, the protector, the mother and father of Ebora. The tree-god feeds us with his roots, he exalts us in his branches. When our enemy the Jure’lia came last, the Eighth Rain fell from his branches and the worm people were scoured from all of Sarn.’ She paused, pursing her lips, not adding: and then Ygseril died, and left us all to die too.

‘The Eighth Rain, when the last war-beasts were born!’ Louis stared up at the vast breadth of the trunk looming above them, a smile on his round, honest face. ‘The last great battle. My dad said that the Eboran warriors wore armour so bright no one could look at it, that they rode on the backs of snowy white griffins, and their swords blazed with fire. The great pestilence of the Jure’lia queen and the worm people was driven back and her Behemoths were scattered to pieces.’ He stopped. In his enthusiasm for the old battle stories he had finally relaxed in her presence. ‘The corpse moon frightens me,’ he confided. ‘My nan says that if you should catch it winking at you, you’ll die by the next sunset.’

Peasant nonsense, thought Hestillion. The corpse moon was just another wrecked Behemoth, caught in the sky like a fly in amber. They had reached the edge of the marble now, capped with an obsidian ring. Beyond that the roots twisted and tangled, rising up like the curved backs of silver-green sea monsters. When Hestillion made to step out onto the roots, Louis stopped, pulling back sharply on her hand.

‘We mustn’t!’

She looked at his wide eyes, and smiled. She let her hair fall over one shoulder, a shimmering length of pale gold, and threw him the obvious bait. ‘Are you scared?’

The boy frowned, briefly outraged, and they stepped over onto the roots together. He stumbled at first, his boots too stiff to accommodate the rippling texture of the bark, while Hestillion had been climbing these roots as soon as she could walk. Carefully, she guided him further in, until they were close to the enormous bulk of the trunk itself – it filled their vision, a grey-green wall of ridges and whorls. This close it was almost possible to imagine you saw faces in the bark; the sorrowful faces, perhaps, of all the Eborans who had died since the Eighth Rain. The roots under their feet were densely packed, spiralling down into the unseen dark below them. Hestillion knelt, gathering her silk robe to one side so that it wouldn’t get too creased. She tugged her wide yellow belt free of her waist and then wound it around her right arm, covering her sleeve and tying the end under her armpit.

‘Come, kneel next to me.’

Louis looked unsure again, and Hestillion found she could almost read the thoughts on his face. Part of him baulked at the idea of kneeling before a foreign god – even a dead one. She gave him her sunniest smile.

‘Just for fun. Just for a moment.’

Nodding, he knelt on the roots next to her, with somewhat less grace than she had managed. He turned to her, perhaps to make some comment on the strangely slick texture of the wood under his hands, and Hestillion slipped the knife from within her robe, baring it to the subdued light of the Hall of Roots. It was so sharp that she merely had to press it to his throat – she doubted he even saw the blade, so quickly was it over – and in less than a moment the boy had fallen onto his back, blood bubbling thick and red against his fingers. He shivered and kicked, an expression of faint puzzlement on his face, and Hestillion leaned back as far as she could, looking up at the distant branches.

‘Blood for you!’ She took a slow breath. The blood had saturated the belt on her arm and it was rapidly sinking into the silk below – so much for keeping it clean. ‘Life blood for your roots! I pledge you this and more!’

‘Hest!’

The shout came from across the hall. She turned back to see her brother Tormalin standing by the half-open door, a slim shape in the dusty gloom, his black hair like ink against a page. Even from this distance she could see the expression of alarm on his face.

‘Hestillion, what have you done?’ He started to run to her. Hestillion looked down at the body of the wine merchant’s boy, his blood black against the roots, and then up at the branches. There was no answering voice, no fresh buds or running sap. The god was still dead.

‘Nothing,’ she said bitterly. ‘I’ve done nothing at all.’

‘Sister.’ He had reached the edge of the roots, and now she could see how he was trying to hide his horror at what she had done, his face carefully blank. It only made her angrier. ‘Sister, they . . . they have already tried that.’

Tormalin shifted the pack on his back and adjusted his sword belt. He could hear, quite clearly, the sound of a carriage approaching him from behind, but for now he was content to ignore it and the inevitable confrontation it would bring with it. Instead, he looked at the deserted thoroughfare ahead of him, and the corpse moon hanging in the sky, silver in the early afternoon light.

Once this had been one of the greatest streets in the city. Almost all of Ebora’s nobles would have kept a house or two here, and the road would have been filled with carriages and horses, with servants running errands, with carts selling goods from across Sarn, with Eboran ladies, their faces hidden by veils or their hair twisted into towering, elaborate shapes – depending on the fashion that week – and Eboran men clothed in silk, carrying exquisite swords. Now the road was broken, and weeds were growing up through the stone wherever you looked. There were no people here – those few still left alive had moved inward, towards the central palace – but there were wolves. Tormalin had already felt the presence of a couple, matching his stride just out of sight, a pair of yellow eyes glaring balefully from the shadows of a ruined mansion. Weeds and wolves – that was all that was left of glorious Ebora.

The carriage was closer now, the sharp clip of the horses’ hooves painfully loud in the heavy silence. Tormalin sighed, still determined not to look. Far in the distance was the pale line of the Wall. When he reached it, he would spend the night in the sentry tower. When had the sentry towers last been manned? Certainly no one left in the palace would know. The crimson flux was their more immediate concern.

The carriage stopped, and the door clattered open. He didn’t hear anyone step out, but then she had always walked silently.

‘Tormalin!’

He turned, plastering a tight smile on his face. ‘Sister.’

She wore yellow silk, embroidered with black dragons. It was the wrong colour for her – the yellow was too lurid against her pale golden hair, and her skin looked like parchment. Even so, she was the brightest thing on the blighted, wolf-infested road.

‘I can’t believe you are actually going to do this.’ She walked swiftly over to him, holding her robe out of the way of her slippered feet, stepping gracefully over cracks. ‘You have done some stupid, selfish things in your time, but this?’

Tormalin lifted his eyes to the carriage driver, who was very carefully not looking at them. He was a man from the plains, the ruddy skin of his face shadowed by a wide-brimmed cap. A human servant; one of a handful left in Ebora, surely. For a moment, Tormalin was struck by how strange he and his sister must look to him, how alien. Eborans were taller than humans, long-limbed but graceful with it, while their skin – whatever colour it happened to be – shone like finely grained wood. Humans looked so . . . dowdy in comparison. And then there were the eyes, of course. Humans were never keen on Eboran eyes. Tormalin grimaced and turned his attention back to his sister.

‘I’ve been talking about this for years, Hest. I’ve spent the last month putting my affairs in order, collecting maps, organising my travel. Have you really just turned up to express your surprise now?’

She stood in front of him, a full head shorter than him, her eyes blazing. Like his, they were the colour of dried blood, or old wine.

‘You are running away,’ she said. ‘Abandoning us all here, to waste away to nothing.’

‘I will do great good for Ebora,’ he replied, clearing his throat. ‘I intend to travel to all the great seats of power. I will open new trade routes, and spread word of our plight. Help will come to us, eventually.’

‘That is not what you intend to do at all!’ Somewhere in the distance, a wolf howled. ‘Great seats of power? Whoring and drinking in disreputable taverns, more like.’ She leaned closer. ‘You do not intend to come back at all.’

‘Thanks to you it’s been decades since we’ve had any decent wine in the palace, and as for whoring . . .’ He caught the expression on her face and looked away. ‘Ah. Well. I thought I felt you in my dreams last night, little sister. You are getting very good. I didn’t see you, not even once.’

This attempt at flattery only enraged her further. ‘In the last three weeks, the final four members of the high council have come down with the flux. Lady Rellistin coughs her lungs into her handkerchief at every meeting, while her skin breaks and bleeds, and those that are left wander the palace, just watching us all die slowly, fading away into nothing. Aldasair, your own cousin, stopped speaking to anyone months ago, and Ygseril is a dead sentry, watching over the final years of—’

‘And what do you expect me to do about it?’ With some difficulty he lowered his voice, glancing at the carriage driver again. ‘What can I do, Hest? What can you do? I will not stay here and watch them all die. I do not want to witness everything falling apart. Does that make me a coward?’ He raised his arms and dropped them. ‘Then I will be a coward, gladly. I want to get out there, beyond the Wall, and see the world before the flux takes me too. I could have another hundred years to live yet, and I do not want to spend them here. Without Ygseril –’ he paused, swallowing down a surge of sorrow so strong he could almost taste it – ‘we’ll fade away, become decrepit, broken, old.’ He gestured at the deserted road and the ruined houses, their windows like empty eye sockets. ‘What Ebora once was, Hestillion . . .’ he softened his voice, not wanting to hurt her, not when this was already so hard – ‘it doesn’t exist any more. It is a memory, and it will not return. Our time is over, Hest. Old age or the flux will get us eventually. So come with me. There’s so much to see, so many places where people are living. Come with me.’

‘Tormalin the Oathless,’ she spat, taking a step away from him. ‘That’s what they called you, because you were feckless and a layabout, and I thought, how dare they call my brother so? Even in jest. But they were right. You care about nothing but yourself, Oathless one.’

‘I care about you, sister.’ Tormalin suddenly felt very tired, and he had a long walk to find shelter before nightfall. He wished that she’d never followed him out here, that her stubbornness had let them avoid this conversation. ‘But no, I don’t care enough to stay here and watch you all die. I just can’t do it, Hest.’ He cleared his throat, trying to hide the shaking of his voice. ‘I just can’t.’

A desolate wind blew down the thoroughfare, filling the silence between them with the cold sound of dry leaves rustling against stone. For a moment Tormalin felt dizzy, as though he stood on the edge of a precipice, a great empty space pulling him forward. And then Hestillion turned away from him and walked back to the carriage. She climbed inside, and the last thing he saw of his sister was her delicate white foot encased in its yellow silk slipper. The driver brought the horses round – they were restless and glad to leave, clearly smelling wolves nearby – and the carriage left, moving at a fair clip.

He watched them go for a few moments; the only living thing in a dead landscape, the silver branches of Ygseril a frozen cloud behind them. And then he walked away.

Tormalin paused at the top of a low hill. He had long since left the last trailing ruins of the city behind him, and had been travelling through rough scrubland for a day or so. Here and there were the remains of old carts, abandoned lines of them like snake bones in the dust, or the occasional shack that had once served visitors to Ebora. Tor had been impressed to see them still standing, even if a strong wind might shatter them to pieces at any moment; they were remnants from before the Carrion Wars, when humans still made the long journey to Ebora voluntarily. He himself had been little more than a child. Now, a deep purple dusk had settled across the scrubland and at the very edge of Ebora’s ruined petticoats, the Wall loomed above him, its white stones a drab lilac in the fading light.

Tor snorted. This was it. Once he was beyond the Wall he did not intend to come back – for all that he’d claimed to Hestillion, he was no fool. Ebora was a disease, and they were all infected. He had to get out while there were still some pleasures to be had, before he was the one slowly coughing himself to death in a finely appointed bedroom.

Far to the right, a watchtower sprouted from the Wall like a canine tooth, sharp and jagged against the shadow of the mountain. The windows were all dark, but it was still just light enough to see the steps carved there. Once he had a roof over his head he would make a fire and set himself up for the evening. He imagined how he might appear to an observer; the lone adventurer, heading off to places unknown, his storied sword sheathed against the night but ready to be released at the first hint of danger. He lifted his chin, and pictured the sharp angles of his face lit by the eerie glow of the sickle moon, his shining black hair a glossy slick even restrained in its tail. He almost wished he could see himself.

His spirits lifted at the thought of his own adventurousness, he made his way up the steps, finding a new burst of energy at the end of this long day. The tower door was wedged half open with piles of dry leaves and other debris from the forest. If he’d been paying attention, he’d have noted that the leaves had recently been pushed to one side, and that within the tower all was not as dark as it should have been, but Tor was thinking of the wineskin in his pack and the round of cheese wrapped in pale wax. He’d been saving them for the next time he had a roof over his head, and he’d decided that this ramshackle tower counted well enough.

He followed the circular steps up to the tower room. The door here was shut, but he elbowed it open easily enough, half falling through into the circular space beyond.

Movement, scuffling, and light. He had half drawn his sword before he recognised the scruffy shape by the far window as human – a man, his dark eyes bright in a dirty face. There was a small smoky fire in the middle of the room, the two windows covered over with broken boards and rags. A wave of irritation followed close on the back of his initial alarm; he had not expected to see humans in this place.

‘What are you doing here?’ Tor paused, and pushed his sword back into its scabbard. He looked around the tower room. There were signs that the place had been inhabited for a short time at least – the bones of small fowl littered the stone floor, their ends gnawed. Dirty rags and two small tin bowls, crusted with something, and a half-empty bottle of some dark liquid. Tor cleared his throat.

‘Well? Do you not speak?’

The man had greasy yellow hair and a suggestion of a yellow beard. He still stood pressed against the wall, but his shoulders abruptly drooped, as though the energy he’d been counting on to flee had left him.

‘If you will not speak, I will have to share your fire.’ Tor pushed away a pile of rags with his boot and carefully seated himself on the floor, his legs crossed. It occurred to him that if he got his wineskin out now he would feel compelled to share it with the man. He resolved to save it one more night. Instead, he shouldered off his pack and reached inside it for his small travel teapot. The fire was pathetic but with a handful of the dried leaves he had brought for the purpose, it was soon looking a little brighter. The water would boil eventually.

The man was still staring at him. Tor busied himself with emptying a small quantity of his water supply into a shallow tin bowl, and searching through his bag for one of the compact bags of tea he had packed.

‘Eboran.’ The man’s voice was a rusted hinge, and he spoke a variety of plains speech Tor knew well. He wondered how long it had been since the man had spoken to anyone. ‘Blood sucker. Murderer.’

Tor cleared his throat and switched to the man’s plains dialect. ‘It’s like that, is it?’ He sighed and sat back from the fire and his teapot. ‘I was going to offer you tea, old man.’

‘You call me old?’ The man laughed. ‘You? My grandfather told me stories of the Carrion Wars. You bloodsuckers. Eatin’ people alive on the battlefield, that’s what my grandfather said.’

Tor thought of the sword again. The man was trespassing on Eboran land, technically.

‘Your grandfather would not have been alive. The Carrion Wars were over three hundred years ago.’

None of them would have been alive then, of course, yet they all still acted as though it were a personal insult. Why did they have to pass the memory on? Down through the years they passed on the stories, like they passed on brown eyes, or ears that stuck out. Why couldn’t they just forget?

‘It wasn’t like that.’ Tor poked at the tin bowl, annoyed with how tight his voice sounded. Abruptly, he wished that the windows weren’t boarded up. He was stuck in here with the smell of the man. ‘No one wanted . . . when Ygseril died . . . he had always fed us, nourished us. Without him, we were left with the death of our entire people. A slow fading into nothing.’

The man snorted with amusement. Amazingly, he came over to the fire and crouched there.

‘Your tree-god died, aye, and took your precious sap away with it. Maybe you all should have died then, rather than getting a taste for our blood. Maybe that was what should have happened.’

The man settled himself, his dark eyes watching Tor closely, as though he expected an explanation of some sort. An explanation for generations of genocide.

‘What are you doing up here? This is an outpost. Not a refuge for tramps.’

The man shrugged. From under a pile of rags he produced a grease-smeared silver bottle. He uncapped it and took a swig. Tor caught a whiff of strong alcohol.

‘I’m going to see my daughter,’ he said. ‘Been away for years. Earning coin, and then losing it. Time to go home, see what’s what. See who’s still alive. My people had a settlement in the forest west of here. I’ll be lucky if you Eborans have left anyone alive there, I suppose.’

‘Your people live in a forest?’ Tor raised his eyebrows. ‘A quiet one, I hope?’

The man’s dirty face creased into half a smile. ‘Not as quiet as we’d like, but where is, now? This world is poisoned. Oh, we have thick strong walls, don’t you worry about that. Or at least, we did.’

‘Why leave your family for so long?’ Tor was thinking of Hestillion. The faint scuff of yellow slippers, the scent of her weaving through his dreams. Dream-walking had always been her particular talent.

‘Ah, I was a different man then,’ he replied, as though that explained everything. ‘Are you going to take my blood?’

Tor scowled. ‘As I’m sure you know, human blood wasn’t the boon it was thought to be. There is no true replacement for Ygseril’s sap, after all. Those who overindulged . . . suffered for it. There are arrangements now. Agreements with humans, for whom we care.’ He sat up a little straighter. If he’d chosen to walk to another watchtower, he could be drinking his wine now. ‘They are compensated, and we continue to use the blood in . . . small doses.’ He didn’t add that it hardly mattered – the crimson flux seemed largely unconcerned with exactly how much blood you had consumed, after all. ‘It’s not very helpful when you try and make everything sound sordid.’

The man bellowed with laughter, rocking back and forth and clutching at his knees. Tor said nothing, letting the man wear himself out. He went back to preparing tea. When the man’s laughs had died down to faint snifflings, Tor pulled out two clay cups from his bag and held them up.

‘Will you drink tea with Eboran scum?’

For a moment the man said nothing at all, although his face grew very still. The small amount of water in the shallow tin bowl was hot, so Tor poured it into the pot, dousing the shrivelled leaves. A warm, spicy scent rose from the pot, almost immediately lost in the sour-sweat smell of the room.

‘I saw your sword,’ said the man. ‘It’s a fine one. You don’t see swords like that any more. Where’d you get it?’

Tor frowned. Was he suggesting he’d stolen it? ‘It was my father’s sword. Winnow-forged steel, if you must know. It’s called the Ninth Rain.’

The man snorted at that. ‘We haven’t had the Ninth Rain yet. The last one was the eighth. I would have thought you’d remember that. Why call it the Ninth Rain?’

‘It is a long and complicated story, one I do not wish to share with a random human who has already insulted me more than once.’

‘I should kill you,’ said the man quietly. ‘One less Eboran. That would make the world safer for my daughter, wouldn’t it?’

‘You are quite welcome to try,’ said Tor. ‘Although I think having her father with her when she was growing through her tender years would have been a better effort at making the world safer for your daughter.’

The man grew quiet, then. When Tor offered him the tea he took it, nodding once in what might have been thanks, or perhaps acceptance. They drank in silence, and Tor watched the wisps of black smoke curling up near the ceiling, escaping through some crack up there. Eventually, the man lay down on his side of the fire with his back to Tor, and he supposed that was as much trust as he would get from a human. He pulled out his own bed roll, and made himself as comfortable as he could on the stony floor. There was a long way to travel yet, and likely worse places to sleep in the future.

Tor awoke to a stuffy darkness, a thin line of grey light leaking in at the edge of the window letting him know it was dawn. The man was still asleep next to the embers of their fire. Tor gathe

Title Page

Copyright Page

About Jen Williams

Praise

Also by Jen Williams

The Ninth Rain Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Acknowledgements

The Bitter Twins Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Acknowledgements

The Poison Song Title Page

About the Book

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Acknowledgements

‘Will we get into trouble?’

Hestillion took hold of the boy’s hand and gave it a quick squeeze. When he looked up at her, his eyes were wide and glassy – he was afraid. The few humans who came to Ebora generally were. She favoured him with a smile and they walked a little faster down the echoing corridor. To either side of them enormous oil paintings hung on the walls, dusty and grey. A few of them had been covered with sheets, like corpses.

‘Of course not, Louis. You are with me, aren’t you? I can go anywhere in the palace I like, and you are my friend.’

‘I’ve heard that people can go mad, just looking at it.’ He paused, as if sensing that he might have said something wrong. ‘Not Eborans, I mean. Other people, from outside.’

Hestillion smiled again, more genuinely this time. She had sensed this from the delegates’ dreams. Ygseril sat at the centre of their night wanderings, usually unseen but always there, his roots creeping in at the corners. They were all afraid of him: bad dreams conjured by thousands of years’ worth of the stories and rumours. Hestillion had kept herself carefully hidden while exploring their nightmares. Humans did not care for the Eboran art of dream-walking.

‘It is quite a startling sight, I promise you that, but it cannot harm you.’ In truth, the boy would already have seen Ygseril, at least partly. The tree-god’s great cloud of silvery branches burst up above the roof of the palace, and it was possible to see it from the Wall, and even the foothills of the mountains; or so she had been told. The boy and his father, the wine merchant, could hardly have missed it as they made their way into Ebora. They would have found themselves watching the tree-god as they rode their tough little mountain ponies down into the valley, wine sloshing rhythmically inside wooden casks. Hestillion had seen that in their dreams, too. ‘Here we are, look.’

At the end of the corridor was a set of elaborately carved double doors. Once, the phoenixes and dragons etched into the wood would have been painted gold, their eyes burning bright and every tooth and claw and talon picked out in mother-of-pearl, but it had all peeled off or been worn away, left as dusty and as sad as everything else in Ebora. Hestillion leaned her weight on one of the doors and it creaked slowly open, showering them in a light rain of dust. Inside was the cavernous Hall of Roots. She waited for Louis to gather himself.

‘I . . . oh, it’s . . .’ He reached up as if to take off his cap, then realised he had left it in his room. ‘My lady Hestillion, this is the biggest place I’ve ever seen!’

Hestillion nodded. She didn’t doubt that it was. The Hall of Roots sat at the centre of the palace, which itself sat in the centre of Ebora. The floor under their feet was pale green marble etched with gold – this, at least, had yet to be worn away – and above them the ceiling was a glittering lattice of crystal and finely spun lead, letting in the day’s weak sunshine. And bursting out of the marble was Ygseril himself; ancient grey-green bark, rippled and twisted, a curling confusion of roots that sprawled in every direction, and branches, high above them, reaching through the circular hole in the roof, empty of leaves. Little pieces of blue sky glittered there, cut into shards by the arms of Ygseril. The bark on the trunk of the tree was wrinkled and ridged, like the skin of a desiccated corpse. Which was, she supposed, entirely appropriate.

‘What do you think?’ she pressed. ‘What do you think of our god?’

Louis twisted his lips together, obviously trying to think of some answer that would please her. Hestillion held her impatience inside. Sometimes she felt like she could reach in and pluck the stuttering thoughts from the minds of these slow-witted visitors. Humans were just so uncomplicated.

‘It is very fine, Lady Hestillion,’ he said eventually. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it, not even in the deepest vine forests, and my father says that’s where the oldest trees in all of Sarn grow.’

‘Well, strictly speaking, he is not really a tree.’ Hestillion walked Louis across the marble floor, towards the place where the roots began. The boy’s leather boots made odd flat notes of his footsteps, while her silk slippers gave only the faintest whisper. ‘He is the heart, the protector, the mother and father of Ebora. The tree-god feeds us with his roots, he exalts us in his branches. When our enemy the Jure’lia came last, the Eighth Rain fell from his branches and the worm people were scoured from all of Sarn.’ She paused, pursing her lips, not adding: and then Ygseril died, and left us all to die too.

‘The Eighth Rain, when the last war-beasts were born!’ Louis stared up at the vast breadth of the trunk looming above them, a smile on his round, honest face. ‘The last great battle. My dad said that the Eboran warriors wore armour so bright no one could look at it, that they rode on the backs of snowy white griffins, and their swords blazed with fire. The great pestilence of the Jure’lia queen and the worm people was driven back and her Behemoths were scattered to pieces.’ He stopped. In his enthusiasm for the old battle stories he had finally relaxed in her presence. ‘The corpse moon frightens me,’ he confided. ‘My nan says that if you should catch it winking at you, you’ll die by the next sunset.’

Peasant nonsense, thought Hestillion. The corpse moon was just another wrecked Behemoth, caught in the sky like a fly in amber. They had reached the edge of the marble now, capped with an obsidian ring. Beyond that the roots twisted and tangled, rising up like the curved backs of silver-green sea monsters. When Hestillion made to step out onto the roots, Louis stopped, pulling back sharply on her hand.

‘We mustn’t!’

She looked at his wide eyes, and smiled. She let her hair fall over one shoulder, a shimmering length of pale gold, and threw him the obvious bait. ‘Are you scared?’

The boy frowned, briefly outraged, and they stepped over onto the roots together. He stumbled at first, his boots too stiff to accommodate the rippling texture of the bark, while Hestillion had been climbing these roots as soon as she could walk. Carefully, she guided him further in, until they were close to the enormous bulk of the trunk itself – it filled their vision, a grey-green wall of ridges and whorls. This close it was almost possible to imagine you saw faces in the bark; the sorrowful faces, perhaps, of all the Eborans who had died since the Eighth Rain. The roots under their feet were densely packed, spiralling down into the unseen dark below them. Hestillion knelt, gathering her silk robe to one side so that it wouldn’t get too creased. She tugged her wide yellow belt free of her waist and then wound it around her right arm, covering her sleeve and tying the end under her armpit.

‘Come, kneel next to me.’

Louis looked unsure again, and Hestillion found she could almost read the thoughts on his face. Part of him baulked at the idea of kneeling before a foreign god – even a dead one. She gave him her sunniest smile.

‘Just for fun. Just for a moment.’

Nodding, he knelt on the roots next to her, with somewhat less grace than she had managed. He turned to her, perhaps to make some comment on the strangely slick texture of the wood under his hands, and Hestillion slipped the knife from within her robe, baring it to the subdued light of the Hall of Roots. It was so sharp that she merely had to press it to his throat – she doubted he even saw the blade, so quickly was it over – and in less than a moment the boy had fallen onto his back, blood bubbling thick and red against his fingers. He shivered and kicked, an expression of faint puzzlement on his face, and Hestillion leaned back as far as she could, looking up at the distant branches.

‘Blood for you!’ She took a slow breath. The blood had saturated the belt on her arm and it was rapidly sinking into the silk below – so much for keeping it clean. ‘Life blood for your roots! I pledge you this and more!’

‘Hest!’

The shout came from across the hall. She turned back to see her brother Tormalin standing by the half-open door, a slim shape in the dusty gloom, his black hair like ink against a page. Even from this distance she could see the expression of alarm on his face.

‘Hestillion, what have you done?’ He started to run to her. Hestillion looked down at the body of the wine merchant’s boy, his blood black against the roots, and then up at the branches. There was no answering voice, no fresh buds or running sap. The god was still dead.

‘Nothing,’ she said bitterly. ‘I’ve done nothing at all.’

‘Sister.’ He had reached the edge of the roots, and now she could see how he was trying to hide his horror at what she had done, his face carefully blank. It only made her angrier. ‘Sister, they . . . they have already tried that.’

Tormalin shifted the pack on his back and adjusted his sword belt. He could hear, quite clearly, the sound of a carriage approaching him from behind, but for now he was content to ignore it and the inevitable confrontation it would bring with it. Instead, he looked at the deserted thoroughfare ahead of him, and the corpse moon hanging in the sky, silver in the early afternoon light.

Once this had been one of the greatest streets in the city. Almost all of Ebora’s nobles would have kept a house or two here, and the road would have been filled with carriages and horses, with servants running errands, with carts selling goods from across Sarn, with Eboran ladies, their faces hidden by veils or their hair twisted into towering, elaborate shapes – depending on the fashion that week – and Eboran men clothed in silk, carrying exquisite swords. Now the road was broken, and weeds were growing up through the stone wherever you looked. There were no people here – those few still left alive had moved inward, towards the central palace – but there were wolves. Tormalin had already felt the presence of a couple, matching his stride just out of sight, a pair of yellow eyes glaring balefully from the shadows of a ruined mansion. Weeds and wolves – that was all that was left of glorious Ebora.

The carriage was closer now, the sharp clip of the horses’ hooves painfully loud in the heavy silence. Tormalin sighed, still determined not to look. Far in the distance was the pale line of the Wall. When he reached it, he would spend the night in the sentry tower. When had the sentry towers last been manned? Certainly no one left in the palace would know. The crimson flux was their more immediate concern.

The carriage stopped, and the door clattered open. He didn’t hear anyone step out, but then she had always walked silently.

‘Tormalin!’

He turned, plastering a tight smile on his face. ‘Sister.’

She wore yellow silk, embroidered with black dragons. It was the wrong colour for her – the yellow was too lurid against her pale golden hair, and her skin looked like parchment. Even so, she was the brightest thing on the blighted, wolf-infested road.

‘I can’t believe you are actually going to do this.’ She walked swiftly over to him, holding her robe out of the way of her slippered feet, stepping gracefully over cracks. ‘You have done some stupid, selfish things in your time, but this?’

Tormalin lifted his eyes to the carriage driver, who was very carefully not looking at them. He was a man from the plains, the ruddy skin of his face shadowed by a wide-brimmed cap. A human servant; one of a handful left in Ebora, surely. For a moment, Tormalin was struck by how strange he and his sister must look to him, how alien. Eborans were taller than humans, long-limbed but graceful with it, while their skin – whatever colour it happened to be – shone like finely grained wood. Humans looked so . . . dowdy in comparison. And then there were the eyes, of course. Humans were never keen on Eboran eyes. Tormalin grimaced and turned his attention back to his sister.

‘I’ve been talking about this for years, Hest. I’ve spent the last month putting my affairs in order, collecting maps, organising my travel. Have you really just turned up to express your surprise now?’

She stood in front of him, a full head shorter than him, her eyes blazing. Like his, they were the colour of dried blood, or old wine.

‘You are running away,’ she said. ‘Abandoning us all here, to waste away to nothing.’

‘I will do great good for Ebora,’ he replied, clearing his throat. ‘I intend to travel to all the great seats of power. I will open new trade routes, and spread word of our plight. Help will come to us, eventually.’

‘That is not what you intend to do at all!’ Somewhere in the distance, a wolf howled. ‘Great seats of power? Whoring and drinking in disreputable taverns, more like.’ She leaned closer. ‘You do not intend to come back at all.’

‘Thanks to you it’s been decades since we’ve had any decent wine in the palace, and as for whoring . . .’ He caught the expression on her face and looked away. ‘Ah. Well. I thought I felt you in my dreams last night, little sister. You are getting very good. I didn’t see you, not even once.’

This attempt at flattery only enraged her further. ‘In the last three weeks, the final four members of the high council have come down with the flux. Lady Rellistin coughs her lungs into her handkerchief at every meeting, while her skin breaks and bleeds, and those that are left wander the palace, just watching us all die slowly, fading away into nothing. Aldasair, your own cousin, stopped speaking to anyone months ago, and Ygseril is a dead sentry, watching over the final years of—’

‘And what do you expect me to do about it?’ With some difficulty he lowered his voice, glancing at the carriage driver again. ‘What can I do, Hest? What can you do? I will not stay here and watch them all die. I do not want to witness everything falling apart. Does that make me a coward?’ He raised his arms and dropped them. ‘Then I will be a coward, gladly. I want to get out there, beyond the Wall, and see the world before the flux takes me too. I could have another hundred years to live yet, and I do not want to spend them here. Without Ygseril –’ he paused, swallowing down a surge of sorrow so strong he could almost taste it – ‘we’ll fade away, become decrepit, broken, old.’ He gestured at the deserted road and the ruined houses, their windows like empty eye sockets. ‘What Ebora once was, Hestillion . . .’ he softened his voice, not wanting to hurt her, not when this was already so hard – ‘it doesn’t exist any more. It is a memory, and it will not return. Our time is over, Hest. Old age or the flux will get us eventually. So come with me. There’s so much to see, so many places where people are living. Come with me.’

‘Tormalin the Oathless,’ she spat, taking a step away from him. ‘That’s what they called you, because you were feckless and a layabout, and I thought, how dare they call my brother so? Even in jest. But they were right. You care about nothing but yourself, Oathless one.’

‘I care about you, sister.’ Tormalin suddenly felt very tired, and he had a long walk to find shelter before nightfall. He wished that she’d never followed him out here, that her stubbornness had let them avoid this conversation. ‘But no, I don’t care enough to stay here and watch you all die. I just can’t do it, Hest.’ He cleared his throat, trying to hide the shaking of his voice. ‘I just can’t.’

A desolate wind blew down the thoroughfare, filling the silence between them with the cold sound of dry leaves rustling against stone. For a moment Tormalin felt dizzy, as though he stood on the edge of a precipice, a great empty space pulling him forward. And then Hestillion turned away from him and walked back to the carriage. She climbed inside, and the last thing he saw of his sister was her delicate white foot encased in its yellow silk slipper. The driver brought the horses round – they were restless and glad to leave, clearly smelling wolves nearby – and the carriage left, moving at a fair clip.

He watched them go for a few moments; the only living thing in a dead landscape, the silver branches of Ygseril a frozen cloud behind them. And then he walked away.

Tormalin paused at the top of a low hill. He had long since left the last trailing ruins of the city behind him, and had been travelling through rough scrubland for a day or so. Here and there were the remains of old carts, abandoned lines of them like snake bones in the dust, or the occasional shack that had once served visitors to Ebora. Tor had been impressed to see them still standing, even if a strong wind might shatter them to pieces at any moment; they were remnants from before the Carrion Wars, when humans still made the long journey to Ebora voluntarily. He himself had been little more than a child. Now, a deep purple dusk had settled across the scrubland and at the very edge of Ebora’s ruined petticoats, the Wall loomed above him, its white stones a drab lilac in the fading light.

Tor snorted. This was it. Once he was beyond the Wall he did not intend to come back – for all that he’d claimed to Hestillion, he was no fool. Ebora was a disease, and they were all infected. He had to get out while there were still some pleasures to be had, before he was the one slowly coughing himself to death in a finely appointed bedroom.

Far to the right, a watchtower sprouted from the Wall like a canine tooth, sharp and jagged against the shadow of the mountain. The windows were all dark, but it was still just light enough to see the steps carved there. Once he had a roof over his head he would make a fire and set himself up for the evening. He imagined how he might appear to an observer; the lone adventurer, heading off to places unknown, his storied sword sheathed against the night but ready to be released at the first hint of danger. He lifted his chin, and pictured the sharp angles of his face lit by the eerie glow of the sickle moon, his shining black hair a glossy slick even restrained in its tail. He almost wished he could see himself.

His spirits lifted at the thought of his own adventurousness, he made his way up the steps, finding a new burst of energy at the end of this long day. The tower door was wedged half open with piles of dry leaves and other debris from the forest. If he’d been paying attention, he’d have noted that the leaves had recently been pushed to one side, and that within the tower all was not as dark as it should have been, but Tor was thinking of the wineskin in his pack and the round of cheese wrapped in pale wax. He’d been saving them for the next time he had a roof over his head, and he’d decided that this ramshackle tower counted well enough.

He followed the circular steps up to the tower room. The door here was shut, but he elbowed it open easily enough, half falling through into the circular space beyond.

Movement, scuffling, and light. He had half drawn his sword before he recognised the scruffy shape by the far window as human – a man, his dark eyes bright in a dirty face. There was a small smoky fire in the middle of the room, the two windows covered over with broken boards and rags. A wave of irritation followed close on the back of his initial alarm; he had not expected to see humans in this place.

‘What are you doing here?’ Tor paused, and pushed his sword back into its scabbard. He looked around the tower room. There were signs that the place had been inhabited for a short time at least – the bones of small fowl littered the stone floor, their ends gnawed. Dirty rags and two small tin bowls, crusted with something, and a half-empty bottle of some dark liquid. Tor cleared his throat.

‘Well? Do you not speak?’

The man had greasy yellow hair and a suggestion of a yellow beard. He still stood pressed against the wall, but his shoulders abruptly drooped, as though the energy he’d been counting on to flee had left him.

‘If you will not speak, I will have to share your fire.’ Tor pushed away a pile of rags with his boot and carefully seated himself on the floor, his legs crossed. It occurred to him that if he got his wineskin out now he would feel compelled to share it with the man. He resolved to save it one more night. Instead, he shouldered off his pack and reached inside it for his small travel teapot. The fire was pathetic but with a handful of the dried leaves he had brought for the purpose, it was soon looking a little brighter. The water would boil eventually.

The man was still staring at him. Tor busied himself with emptying a small quantity of his water supply into a shallow tin bowl, and searching through his bag for one of the compact bags of tea he had packed.

‘Eboran.’ The man’s voice was a rusted hinge, and he spoke a variety of plains speech Tor knew well. He wondered how long it had been since the man had spoken to anyone. ‘Blood sucker. Murderer.’

Tor cleared his throat and switched to the man’s plains dialect. ‘It’s like that, is it?’ He sighed and sat back from the fire and his teapot. ‘I was going to offer you tea, old man.’

‘You call me old?’ The man laughed. ‘You? My grandfather told me stories of the Carrion Wars. You bloodsuckers. Eatin’ people alive on the battlefield, that’s what my grandfather said.’

Tor thought of the sword again. The man was trespassing on Eboran land, technically.

‘Your grandfather would not have been alive. The Carrion Wars were over three hundred years ago.’

None of them would have been alive then, of course, yet they all still acted as though it were a personal insult. Why did they have to pass the memory on? Down through the years they passed on the stories, like they passed on brown eyes, or ears that stuck out. Why couldn’t they just forget?

‘It wasn’t like that.’ Tor poked at the tin bowl, annoyed with how tight his voice sounded. Abruptly, he wished that the windows weren’t boarded up. He was stuck in here with the smell of the man. ‘No one wanted . . . when Ygseril died . . . he had always fed us, nourished us. Without him, we were left with the death of our entire people. A slow fading into nothing.’

The man snorted with amusement. Amazingly, he came over to the fire and crouched there.

‘Your tree-god died, aye, and took your precious sap away with it. Maybe you all should have died then, rather than getting a taste for our blood. Maybe that was what should have happened.’

The man settled himself, his dark eyes watching Tor closely, as though he expected an explanation of some sort. An explanation for generations of genocide.

‘What are you doing up here? This is an outpost. Not a refuge for tramps.’

The man shrugged. From under a pile of rags he produced a grease-smeared silver bottle. He uncapped it and took a swig. Tor caught a whiff of strong alcohol.

‘I’m going to see my daughter,’ he said. ‘Been away for years. Earning coin, and then losing it. Time to go home, see what’s what. See who’s still alive. My people had a settlement in the forest west of here. I’ll be lucky if you Eborans have left anyone alive there, I suppose.’

‘Your people live in a forest?’ Tor raised his eyebrows. ‘A quiet one, I hope?’

The man’s dirty face creased into half a smile. ‘Not as quiet as we’d like, but where is, now? This world is poisoned. Oh, we have thick strong walls, don’t you worry about that. Or at least, we did.’

‘Why leave your family for so long?’ Tor was thinking of Hestillion. The faint scuff of yellow slippers, the scent of her weaving through his dreams. Dream-walking had always been her particular talent.

‘Ah, I was a different man then,’ he replied, as though that explained everything. ‘Are you going to take my blood?’

Tor scowled. ‘As I’m sure you know, human blood wasn’t the boon it was thought to be. There is no true replacement for Ygseril’s sap, after all. Those who overindulged . . . suffered for it. There are arrangements now. Agreements with humans, for whom we care.’ He sat up a little straighter. If he’d chosen to walk to another watchtower, he could be drinking his wine now. ‘They are compensated, and we continue to use the blood in . . . small doses.’ He didn’t add that it hardly mattered – the crimson flux seemed largely unconcerned with exactly how much blood you had consumed, after all. ‘It’s not very helpful when you try and make everything sound sordid.’

The man bellowed with laughter, rocking back and forth and clutching at his knees. Tor said nothing, letting the man wear himself out. He went back to preparing tea. When the man’s laughs had died down to faint snifflings, Tor pulled out two clay cups from his bag and held them up.

‘Will you drink tea with Eboran scum?’

For a moment the man said nothing at all, although his face grew very still. The small amount of water in the shallow tin bowl was hot, so Tor poured it into the pot, dousing the shrivelled leaves. A warm, spicy scent rose from the pot, almost immediately lost in the sour-sweat smell of the room.

‘I saw your sword,’ said the man. ‘It’s a fine one. You don’t see swords like that any more. Where’d you get it?’

Tor frowned. Was he suggesting he’d stolen it? ‘It was my father’s sword. Winnow-forged steel, if you must know. It’s called the Ninth Rain.’

The man snorted at that. ‘We haven’t had the Ninth Rain yet. The last one was the eighth. I would have thought you’d remember that. Why call it the Ninth Rain?’

‘It is a long and complicated story, one I do not wish to share with a random human who has already insulted me more than once.’

‘I should kill you,’ said the man quietly. ‘One less Eboran. That would make the world safer for my daughter, wouldn’t it?’

‘You are quite welcome to try,’ said Tor. ‘Although I think having her father with her when she was growing through her tender years would have been a better effort at making the world safer for your daughter.’

The man grew quiet, then. When Tor offered him the tea he took it, nodding once in what might have been thanks, or perhaps acceptance. They drank in silence, and Tor watched the wisps of black smoke curling up near the ceiling, escaping through some crack up there. Eventually, the man lay down on his side of the fire with his back to Tor, and he supposed that was as much trust as he would get from a human. He pulled out his own bed roll, and made himself as comfortable as he could on the stony floor. There was a long way to travel yet, and likely worse places to sleep in the future.

Tor awoke to a stuffy darkness, a thin line of grey light leaking in at the edge of the window letting him know it was dawn. The man was still asleep next to the embers of their fire. Tor gathe

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved