- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

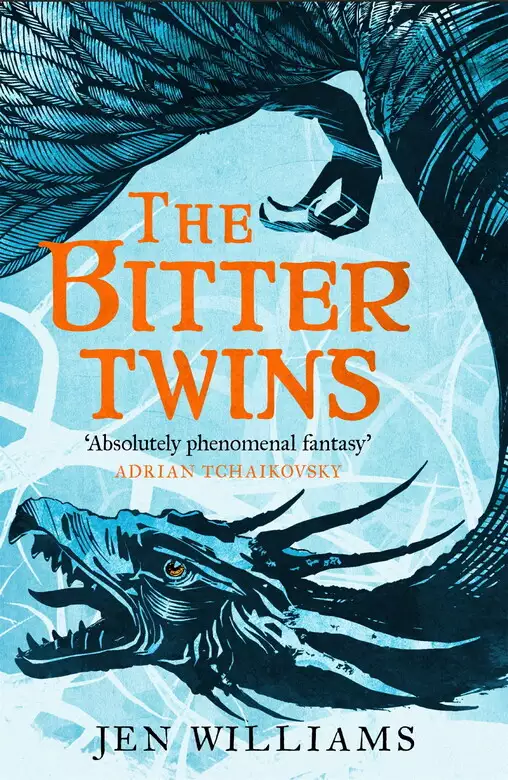

From Jen Williams, highlyacclaimed author of the Copper Cat trilogy and three-time British Fantasy Award finalist, comes the second novel in the electrifying Winnowing Flame trilogy—the sequel to The Ninth Rain. Epic fantasy for fans of Robin Hobb and Adrian Tchaikovsky.

The Ninth Rain has fallen. The Jure'lia are awake. Nothing can be the same again.

Tormalin the Oathless and the fell-witch Noon have their work cut out rallying the first war-beasts to be born in Ebora for three centuries. But these are not the great winged warriors of old. Hatched too soon and with no memory of their past incarnations, these onetime defenders of Sarn can barely stop bickering, let alone face an ancient enemy who grow stronger each day.

The key to uniting them, according to the scholar Vintage, may lie in a part of Sarn no one really believes exists—a distant island, mysteriously connected to the fate of two legendary Eborans who disappeared long ago. But finding it will mean a perilous journey in a time of war, while new monsters lie in wait for those left behind.

Join the heroes of The Ninth Rain as they battle a terrible evil, the likes of which Sarn has never known.

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Bitter Twins

Jen Williams

SFX

‘Absolutely phenomenal fantasy – a definite must-read’

Adrian Tchaikovsky

‘Williams portrays her characters as flawed but humane, propels the plot with expert pace, and excels at eldritch world-building’

Guardian

‘The Ninth Rain is a fast-paced and vibrant fantasy romp through a new world, full of people you want to spend time with and enemies you’d happily run from’

SciFiNow

‘A cracking story that grips you by the heart and doesn’t let go’

Edward Cox

‘Jen Williams takes us on another great adventure. Fresh, engaging, and full of heart’

Peter Newman

‘The setting is diverse, different and intriguing. The characters feel real and you want to know more about their lives with every turn of the page. This is fantasy adventure at its very best’

Starburst

‘A gem of a book with overtones of the new weird and dashes of horror. I loved it from cover to cover’

Den Patrick

‘A great read with heart and soul and epic beasties’

www.raptureinbooks.com

‘Great pacing, top-notch writing, quality characterisation, plenty of action . . . all make The Ninth Rain a truly enjoyable and absorbing read’

www.thetattooedbookgeek.wordpress.com

‘Brilliantly creative fantasy’

www.thisnortherngal.co.uk

‘My only grievance with the trilogy is this: it’s not published in full yet! . . . the wait will likely kill me’

www.liisthinks.blog

‘A fresh take on classic tropes . . . 21st century fantasy at its best’

SFX magazine

‘A highly inventive, vibrant high fantasy with a cast you can care about . . . There is never a dull moment’

The British Fantasy Society

‘Williams has thrown out the rulebook and injected a fun tone into epic fantasy without lightening or watering down the excitement and adventure . . . Highly recommended’

Independent

‘A fast-paced and original new voice in heroic fantasy’

Adrian Tchaikovsky

‘Expect dead gods, mad magic, piracy on the high seas, peculiar turns and pure fantasy fun’

Starburst magazine

‘Absolutely stuffed with ghoulish action. There is never a dull page’

SciFiNow

‘An enthralling adventure’

Sci-Fi Bulletin

‘An utterly outstanding and thrilling ride’

www.brizzlelassbooks.wordpress.com

‘I’ve loved every minute of this story’

www.overtheeffingrainbow.co.uk

‘If only all fantasy was as addictive as this’

www.theeloquentpage.co.uk

‘Just as magical, just as action packed, just as clever and just as much fun as its predecessor . . . You’ll find a great deal to enjoy here’

www.fantasy-faction.com

‘Atmospheric and vivid . . . with a rich history and mythology and colourful, well-written and complex characters, that all combine to suck you in to the world and keep you enchanted up until the very last page’

www.realitysabore.blogspot.co.uk

‘A wonderful sword and sorcery novel with some very memorable characters and a dragon to boot. If you enjoy full-throttle action, awesome monsters, and fun, snarky dialogues then The Copper Promise is definitely a story you won’t want to miss’

www.afantasticallibrarian.com

‘The Copper Promise is dark, often bloody, frequently frightening, but there’s also bucket loads of camaraderie, sarcasm, and an unashamed love of fantasy and the fantastic’

Den Patrick, author of The Boy with the Porcelain Blade

‘The characterisation is second to none, and there are some great new innovations and interesting reworkings of old tropes . . . This book may have been based on the promise of copper but it delivers gold’

Quicksilver on Goodreads

‘It is a killer of a fantasy novel that is indicative of how the classic genre of sword and sorcery is not only still very much alive, but also still the best the genre has to offer’

www.leocristea.wordpress.com

‘What to do with all the flesh, and all the bone? That was the question no one had considered, of course.

‘Human beings are not, after all, simple bags of blood. At the end of all the fighting, the battlefields of the Carrion Wars were heaped with bodies – actual hills of bodies, corpses so numerous that they dammed rivers and caused floods. The crows and the ravens and the other scavenging birds turned the sky black. It was quite a sight. I made many drawings, many paintings.

‘Obviously, once we had taken what we needed, we left them there – it was not Ebora’s problem, what became of those bloodless bodies, and the plains people were, quite understandably, reluctant to come and collect them, so the human corpses stayed right where they were and rotted into the ground. The animals had their feed, and the bones were left to litter the battlefields like grains of rice cast onto the floor. Sometimes, when it is quiet here in my rooms, I listen and I think I can hear the ghosts calling me, crying out in their hundreds, their thousands. I want to get up and sketch them, but I sit with the charcoal in my hand and do nothing. There is no imagining their multitudes, and no way to capture it on canvas.

‘I did not fight in the Carrion Wars, but I was there to witness the horror. Arnia curls her lip at me and says nothing, but it is clear enough what she thinks of that. I think it is important someone is here to witness these things, or at least, I used to think so. Perhaps if I hadn’t been there to witness the slaughter and carry those heavy images in my head, I would have made different decisions and we wouldn’t be where we are now, with the burdens we now carry.

‘I still hear the ghosts sometimes, and they call me unto death, where I belong.’

The words of Micanal the Clearsighted, taken directly from what I must assume is his most personal journal. Quite the gloomy sod, but I cannot deny there is real poetry in his writing – which is not surprising, given that he was Ebora’s most celebrated artist: a genius in a nation of masters. And whatever I might think about his tendency towards melodrama, there are clues here – to the reality of the Carrion Wars and the devastation the crimson flux wrought on the Eboran people – that are without doubt, a staggering gift to my own studies.

Extract from the private journals of Lady Vincenza ‘Vintage’ de Grazon

‘What have I done?’

Hestillion clung to the silver pod, hugging it to her chest as though it were the only solid thing in existence. There was a yawning sensation in the pit of her stomach.

‘What is wrong, Hestillion Eskt, born in the year of the green bird?’

Hestillion looked up. She was kneeling on the floor of a room unlike anything she’d seen before. The walls were a soft, fleshy grey, punctured here and there with odd fibrous growths, small lights hanging at the end of each. The ceiling above her was a shifting mass of black liquid: the same black liquid that had reached down for them from the corpse moon. She could still feel the strange prickly sensation it had left against her skin – it had been obscenely hot, like the hand of a person wracked with fever. With a jolt, she remembered where she was.

‘I am inside the corpse moon.’

The queen moved into sight, then, moving languidly on legs of the shifting black liquid. Her face, a white mask resting on a bed of the stuff, seemed to grow more certain as she looked at Hestillion: the features a little stronger, a little more distinct. She smiled, an uncanny stretching of her lips.

‘The corpse moon? That is what you call it?’

Hestillion took a breath. ‘No, not truly. It’s what the humans called it. They never saw it alive, after all. Not the ones that are around now, anyway.’

The queen tipped her head to one side. ‘We like it. The corpse moon.’

There was a hum, and the room shook faintly, a soft vibration that travelled up through Hestillion’s slippers and into her bones. Seeing her look of surprise, the queen stepped over to her – the movement strange and elongated – and, leaning down, pressed a narrow finger to the floor. Immediately, the soft grey material grew translucent, bleeding outwards like grease on thin paper until, to Hestillion’s horror, she could see the landscape speeding away below them. She gave a little cry, almost falling backwards.

‘We travel up and away now, you see,’ said the queen. ‘We are worn and broken and old, but we can do that.’

Hestillion swallowed hard. They were so high in the sky she could barely fathom it. Her beloved Ebora was there below, recognisable from its marble and its wide streets, but as she watched, a white shape moved in front of the impromptu window. A cloud. They were above the clouds. This must be what it is to fly with the war-beasts, she thought, and she gripped the pod a little tighter. It was cold.

‘This makes you uncomfortable.’ It wasn’t a question as such, and when Hestillion looked back up at the queen she saw that the creature was peering at her in genuine curiosity. More alarmingly, the ceiling above her was moving, and long glistening appendages began to ooze out of the black liquid: seven of them, like long multiple-jointed fingers. As she watched, pale orbs began to push through at the end of each, rolling wetly to clear themselves of the black mucus.

Hestillion scrambled to her feet and drew herself up to her full height. She very deliberately did not look at the eyes in the ceiling.

‘What is this? Why have you brought me here?’ Before she could stop it, another question leapt on the tail of the last. ‘What are you?’

‘You are interesting to us, Hestillion Eskt, born in the year of the green bird. And you helped us. We shall help you.’ The patch of translucence suddenly grew, racing away beneath Hestillion’s feet; it was as if she stood on thin air, a terrible drop yawning away below. Her stomach tried to climb out of her throat, and summoning every bit of willpower she had, Hestillion made herself look directly at the queen’s face.

‘Stop it. This is not . . . helping me.’

The queen shrugged, and once again the floor was a solid thing. The eyes in the ceiling retreated too, oozing back into the shifting wetness.

When she trusted herself to speak again, Hestillion kept her voice low. ‘You do not owe me anything, Queen of the Jure’lia.’

‘Queen . . . of the . . . worm people. What interesting words you have. It is to be savoured. Besides which, we owe you very much. You spoke to us, sought us out and roused us from the chill death of the roots. If you had not done that, we would have slept forever, trapped, and might not even have woken when your stinking tree-god crawled back to life. You interest us, very much, and we would not leave you behind. We have said this.’

Hestillion blinked. This was the first example of emotion she had seen from the Jure’lia queen, aside from mild amusement or curiosity. It was easier, and better, to focus on that than the wave of guilt the creature’s words had prompted. Carefully, she placed the war-beast pod on the floor, letting it lean against her legs. She could not quite bear to be out of contact with it, but her arms were beginning to shake – a war-beast pod was not light.

‘I am not a prisoner here, then?’ Hestillion lifted her chin, aware that even standing as tall as she was the queen towered a good three feet over her. ‘I could leave?’

‘Leave? You are welcome to leave, yes.’ The queen gestured at the floor again, and this time, to Hestillion’s horror, it began to grow not only see-through, but soft. Her foot sank down into it, followed by the other, and there was a terrible sensation of something easing away beneath her.

‘Stop! Stop it, that’s not what I meant!’

The floor grew solid again, and the queen smiled her cold smile. After a moment, she lifted her long arms to the ceiling and fibrous black tendrils came down to meet her. Rising from the floor, she sank into the pool of black liquid as though she were sinking into a bath, and then she was gone. Belatedly, Hestillion realised that there were no doors in the room, and no visible way out.

‘Leave, and go where?’ she said to the war-beast pod. Kneeling, she wrapped her arms around it and closed her eyes. ‘Back to the people I’ve helped to destroy? I would be better off falling through this floor, in that case.’

Something was poking into her chest. She reached within her dress and pulled out a rectangular card about as long as her hand. It had been folded so many times it was slashed with creases, but she remembered the picture on the front of the tarla card well enough: green shapes like twisted fingers against a dark background. The Roots. Aldasair had given it to her years ago, and she had kept it, although she couldn’t have said why, and when they had prepared to pour the growth fluid on Ygseril’s roots, she had tucked it inside her gown. For luck, she supposed. Feeling a fresh surge of disgust at her own stupidity, she slid it back where she had found it and put her arms around the war-beast pod again. It remained cold under her touch, and she wondered why she had brought it.

The ice was thinning.

Peering over the side of the well, Eri could see the smudged shape of his own head and shoulders looking back at him: a dark mirror. He wasn’t sure how he knew the ice was thinner, aside from a blurred memory of a hundred winters asking the same question; he had done this before, after all, over and over again. It was possible to think of that as being caught between mirrors. A hundred, a thousand images of himself, the same over and over, caught in this dark mirror forever. Stepping neatly away from that thought, he pressed his hands to the big rock he had lifted onto the lip of the well, and gave it a quick shove. It plummeted down and there was a satisfying crack, followed by a sploosh.

‘Good.’

He would have water from the well again. Through the winter he had taken water from the great steel buckets he had brought indoors just before the cold months truly took their grip on Ebora, and occasionally from handfuls of snow, but mostly he had stayed inside, safe within the walls of Lonefell. But water from the well would be fresher, and not taste of metal. It was one of the things he looked forward to spring for, after all. Mother would be pleased to hear of this sign of the warmer months – she would be glad to get back to the gardens.

The bucket was stiff with frost, but the rope he had kept indoors to save it from the wet rot. In moments he had a bucketful of water as clear as the sky, and before he poured it into the basin he took a mouthful straight from it, grinning as the shock of the cold travelled through his teeth.

‘Brrr.’

Basin in arms, Eri walked back through the frosted gardens. It was too soon yet for shoots, but he could imagine them there, waiting under the ground like tiny green promises. Back inside Lonefell, he took the basin straight through to the kitchens and added more wood to the fire, waiting for the stove to warm. From there he went down the cold stone steps to the larder, grabbing a candle as he went. The larder was a vast place, and the yellow warmth of the candle did not quite light its furthest corners; if anything, it only served to deepen the shadows on the empty shelves.

‘Empty shelves.’

Eri stood and looked at them, a cold worm of worry waking up to twist inside his chest. He had perhaps two shelves of food left down here, if that. Jars of pickled vegetables he had made himself with the last of the vinegar, dried and salted meat from the rabbits he had managed to trap last summer, a pair of ancient cheeses wrapped in thick cloth. He was afraid to open those in case they were completely lost. Time was running out, if there was any left at all.

Eri snatched a packet of the dried meat off the shelf and left, heading up to the kitchens, humming tunelessly to himself, murmuring the occasional word as the fog of forgetfulness lifted.

‘On the fifth day we shall dance, my love . . . and on the sixth you shall sing to me . . .’

He put a small amount of the water on to boil, and put some strips of the old rabbit meat in to soften. A handful of dried herbs and some salt went in next. It would be a warm dinner, at least.

Leaving that to cook – for want of a better word – Eri wandered down the corridor away from the kitchen, walking without thinking to his mother’s rooms. The walls here were covered in bright paintings: of the lands beyond the Tarah-hut Mountains, of the war-beasts in their battle glory, of old Eboran heroes, their armour shining impossibly bright. His mother and father had made the inside of Lonefell bright with paintings and stories, and every room was stuffed with bookcases, each heaving with books. When they took their son into seclusion, they had not wanted him to be bored.

His mother’s room was bright with early morning sunshine – he had already been in here to draw her curtains – and she was a still shape within the bed. The sheets were crisp, and embroidered with a great forest, animals peeping out from between the trunks and branches.

There was a chair by her bed, so Eri sat on it, remembering as he did so that when they had first come to Lonefell, this had been his favourite chair, even though his legs hadn’t quite reached the ground at the time. Now the upholstery was thin, and here and there little puffs of white stuffing were showing through like the thinning hair on an old man’s head.

‘It’s cold, but the ice is melting.’ He looked across the bed at the far side of the room as he spoke. His mother was a series of soft curves that he didn’t quite focus on. ‘Not long now and the garden will be blooming again. Although . . . well, I hope the vegetables do better than they did last year, Mother. I don’t know what it is – maybe it’s just that the soil is tired. Everything around here seems tired.’ Eri stopped, and after a moment he pulled the corner of the blanket back, and with only a small amount of difficulty slid his hand into his mother’s. He still didn’t quite look at her. ‘When we came here, I thought it was all a great adventure. That we were pilgrims of a sort, I suppose, striking out on our own to find our way. You and Father made it seem like that, I think – all of Father’s stories, all the books he brought. He was so excited to read them with me, I remember. And our garden. We were going to grow so many things in it. Exotic foods as well as everything else, and of course I had a whole suite to myself, full of toys. You must have employed every artisan in Ebora, to bring that many toys with you.’ He cleared his throat, and squeezed his mother’s cold fingers.

‘I’m sorry. Now, I realise it must have been terribly sad for you both. Leaving everything behind to come all the way out here. I found some letters . . .’ Eri paused, shivering violently. His stomach growled and when he pulled his jacket closer around his chest, his fingers brushed against ribs that were too prominent. ‘It’s not that I’m snooping, Mother, it’s just that I’ve read every book twice, three times, some of them, and Father didn’t mind.’ He bit his lip, then continued. ‘I found letters from your mother, and from Father’s parents. They weren’t happy about what you’d done, by the sounds of it. Letters full of pleading, and threats. I didn’t realise you had told them they couldn’t see me, but then I suppose I never thought about it.’

A fly had got into the room. It buzzed once past Eri’s ear, making him shiver again, and then threw itself repeatedly against the far window until he stood up and chased it out with a roll of old parchment. That done, he stood by the glass and looked up at a clear sky. Nothing up there today, at least.

‘I think I’m seeing things.’ He looked back at his mother, then just as quickly looked away again. ‘Things in the sky. But that can’t be. Ebora is dead – it died a long time ago, probably when those letters from my grandparents stopped coming. Right? I just need to eat more food, that’s all, and that will be easier soon, it will be easier . . .’ Eri raised a trembling hand to his forehead and pushed away the hair that had fallen into his eyes.

‘Oh, speaking of which . . .’

He straightened his mother’s blankets, bending down to brush a dry kiss against her waxy skull, and then hurried back to the kitchens. His meagre broth had congealed into something that would at least be more flavourful than water, and he quickly slopped it into a bowl. That done, he carried the bowl, spoon sticking out of it, down another long corridor to his father’s study. In here, the books were watchful, too quiet, and the maps on the wall all looked like lies, so he picked his father up and took him back out to the gardens. There was a series of low stone benches facing the frozen pond, and here he sat and slowly ate the hot gruel, his father set upon the ground next to him.

‘You can feel it’s warmer, can’t you?’ The taste of meat, salty on his tongue, had cheered him up somewhat. ‘I didn’t tell Mother, but the larder is nearly empty. This thaw couldn’t come quickly enough.’ He paused to yank a piece of particularly tough meat from between his teeth. ‘Ugh. The rabbits will be back in a few weeks, and if we get some really fine weather, I can range further. I know what you’ll say, but the Wild is still a good distance from Lonefell and there’s a chance of some deer to the east, I’m sure of it. A whole deer would keep . . . would keep me . . . us . . .’

A shadow cast them into darkness. Eri looked up, his heart in his throat, and there it was again. He jumped up so violently his boot hit the bucket of bones, causing a dry clacking noise he automatically ignored. Above them a dragon soared, slow and magnificent in the golden light of the morning. She was low enough for Eri to see the wide pearly scales of her stomach, each as big as his hand, and the fine white feathers of her wings.

‘It can’t be real. Such things don’t exist anymore. I mean, they just don’t. Father?’ Eri looked down, directly into the bucket of bones – something he very rarely did – and the bare yellow reality of his situation was as cold and as shocking as the well water. He gasped, wrenching his eyes away, and looked back up to the dragon. She was turning to the west, banking slowly like an eagle, and it looked as though there was someone riding her. After a moment, the dragon opened her jaws and a bright jet of violet flame leapt forth, like some sort of fantastical flower. It dissipated, and Eri realised he could hear something, something even more extraordinary; the sound of laughter in the wind. It had been decades since he had heard laughter – it was difficult, for a moment, even to remember what it was.

Eri stood and watched the dragon until she was a tiny dot on the horizon, his broth quite forgotten and cold. His father did not venture an opinion.

My dearest Marin,

By Sarn’s broken old bones, I hope this letter finds you safe. I have sent it on to the last address I had for you, and I hope that you are still there – the university at Reidn has good, strong walls, and there are lots of people there. If you can, stay there, Marin. Don’t do anything stupid (not that you would, darling, but your aunt worries so).

I’ve sent a letter home to the vine forest too, but I am on the road and have no way to receive replies. There is a certain amount of safety in remoteness, so the House may not have seen any horrors, but I cannot help thinking of the Behemoth ruins hidden within the forest. They were ancient and little more than shards and broken pieces, and everything I’ve seen suggests that only the remains from recent Rains have been brought back to life, yet . . . Of course I worry.

I travel now with an Eboran woman called Nanthema. I will have mentioned her to you, I think. We’re making our way to Ebora, travelling often at night and avoiding the main roads, although I’m not sure that will help. We must be alert at all times, and it is exhausting; if we are not cowering from the distant sight of the Behemoths lurching through our skies, we are hiding from wolves, or Wild-touched creatures. I am hoping to find help in Ebora, or at least more knowledge of what exactly we face. I have much to tell you, Marin darling, but too much to fit in this letter. I will tell you when I next see your dear, handsome face.

An interesting note about this letter. We have stopped in a town called Nrg, a northern settlement clinging to the Min hills (hills my arse, these things are more or less mountains, my sore feet can attest to that) and they have the most remarkable birds here, huge things that I think must be mildly Wild-touched. They use these birds to send messages, which is, hopefully, how your letter will reach you. However, the woman I spoke to who tends these birds told me that just recently the birds have not been returning. Killed by Behemoth creatures, I asked her? She thought not – it’s possible, she thinks, that the birds have been using the corpse moon to navigate by, and now that it is gone, they are getting lost. Isn’t that remarkable, Marin? There are always new wonders, it seems.

Extract from the private letters of Master Marin de Grazon

When the attack came, Esther was ankle deep in muddy sand with her little brother. The day was a blowy one, punctuated with squalls of rain all the colder for coming in off the sea, and they both had their hoods strapped down tightly. Corin’s was bright blue and sewn with little fish shapes: a present from their grandfather. He had got it for his nameday only the week before, and was still insisting on wearing it at all times, even at dinner. Inside the great shell they were protected from the worst of the weather, but it was still cold and damp.

‘It smells,’ pointed out Corin.

‘Mmm, lovely fishy smell. Smells just like your socks.’ They moved deeper inside, Esther leading the way as Corin stifled his giggles. The smooth, pinkish walls were stained with salt and even a few barnacles, but Esther could see what they were after, just ahead. White mounds with black spots, each about the size of her foot, clung to the shell wall. She took out her knife in readiness.

‘Here we go, Corin. Do you want to do the first one?’

Up close, the sacs of razor crab eggs were more translucent than white, with bulbous grey shadows inside, covered all over in a thick, shivering jelly. Corin frowned deeply; they did not look much like the tasty morsels of brown flesh their father served up for dinner in the evening, and she could see him wondering already if this was worth all the effort.

‘Look, I’ll show you.’ Esther untucked the oilskin sack from her belt and positioned it under the nearest cluster, then took her knife from its sheath. This, she knew, was Corin’s real fascination, so she let the murky light play along the blade for a moment. ‘You take the knife, and then, holding the cluster at the bottom, you see, you just slide it up under, next to the skin of the shell. You have to get it all in one go, otherwise it all falls apart into blobby bits.’

In a practised movement, she slipped the blade underneath and the egg sac fell – with a slightly unpleasant splish, she had to admit – neatly into the awaiting bag.

‘Oh.’ Corin’s expression was hidden within his hood. ‘What’s that?’

‘What’s what?’

It was a hum at first, and then a high-pitched whine that seemed to thrum through the walls of the great shell. Without really knowing why, Esther leaned her hand against the shell wall and felt it vibrating, so deep it made the ends of her fingers go numb.

‘The noise! What is it?’ There was an edge of panic in Corin’s voice, so Esther sheathed her knife and, leaving the bag where it was, took hold of his hand.

‘Probably just a big ship coming in,’ she said, although she knew already that couldn’t be right. No ship could make such a racket. ‘Let’s go and have a look, shall we?’

They walked quickly to the lip of the shell, following its gently spiralling walls with the sand sucking at their boots. Esther’s first thought was that an unexpected storm had rolled in; true, the sea was the same steely band it had been earlier, no tossing waves out there, but Coldreef was in shadow. The wooden palisade that circled the settlement was a series of dark jagged sticks, and the cramped houses, with their mismatched walls of driftwood and razor shell, looked too small, dwindled somehow. And then she looked up.

‘In Tomas’s name.’ Esther snatched Corin up from the sand and held him to her like she hadn’t done since he was four. ‘Corin, we must get inside.’

There was a monster hanging in the sky. To Esther, who had lived in Coldreef all her life, it looked a little like the fat sea beetles she sometimes found dead down by the shore, except it was huge, as big as a thousand Wild-touched razor crabs. It had a bulbous, segmented body, an oily greenish black in colour, with cracks and lines running all across the thing. Here and there were puckering holes that seemed to be expelling a thick black ooze, and odd skittering creatures. Even as she watched, these were falling down towards Coldreef like seeds falling from a tree, many-jointed legs spread wide.

‘What is it, Essie? What is it?’

She had been running awkwardly towards the palisade gate, her only thought to get back to their father, but now the monster was descending – if it kept going, it would simply crush

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...