- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

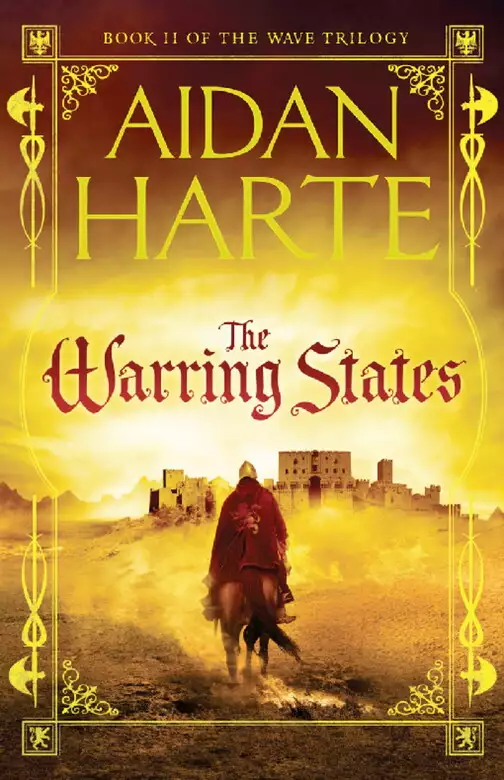

The second book in the Wave Trilogy, set in a darkly original alternative Renaissance Italy. After the rout at Rasenna, Concord faces enemies on all fronts, and nobody believes that the last surviving Apprentice is equal to these crises - but Torbidda didn't become Apprentice by letting himself be manipulated. While Sofia is struggling to understand her miraculous pregnancy, the City of Towers grows wealthy. But it's not long before the people of Rasenna start arguing again, and as the city falls apart once more, Sofia realises she must escape Etruria to save her baby. When prophecy leads her to another cesspit of treachery, the decadent Crusader kingdom of Oltremare, Sofia begins to despair, for this time she can see no way out...

Release date: March 28, 2013

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 440

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Warring States

Aidan Harte

‘You’re pretty slow for an engineer if you can’t see he’s lying.’

‘Signora, you can see there are others waiting. Step aside.’

‘I want something!’

‘Course you do. But even if your son wasn’t too young – how old are you?’

‘Eight,’ the boy said.

‘Even if he were old enough, the Guild only pays for children smart enough to be engineers, and if he were even half as clever as you say, the examiners would have spotted him years ago – and he’d have got further in the al-Buni test today. I’m sorry, but I need you to step aside.’

‘But I told you what a great liar he is. Torbidda, do it properly, or I swear—’

‘I want to go home.’

The examiner shared the boy’s sentiment. He had been sitting in a fine mist of drizzle all morning. His clothes and papers were sodden and his nose dripping, and the dark clouds circling the Molè presaged a squall. He’d seen it a hundred times: destitute parents trying to pawn off mouths they couldn’t feed, never mind that their children were every bit as dull as they were. The Apprentices ought to trust the examiners and stop the annual open testing; they were nothing more than an invitation for fraud. The boy was obviously no Bernoulli – he had a stubborn, ox-like brow and a grim, set jaw. The examiner didn’t blame him for being angry – his mother was trying to sell him, after all.

‘Test him again!’ She struck the boy, an open-handed slap. He didn’t cry, but the examiner could see a scene developing. She turned back, smiling sweetly. ‘This time he’ll do it right.’

‘Signora, look—’

‘Problem here?’ A tall man stopped beside the inspection desk. He was in his late forties, but still fit and strong. He wore a streamlined toga that fell open across his barrel chest as if to advertise his strength. The youthful body was belied by white dartings in his neat beard and the faded ink of the Etruscan numerals beneath the stubble of his shaved head. His bitter mouth pulled down his sharp features.

‘No problem, Grand Selector Flaccus; just a slight delay.’

The woman, recognising in the examiner’s voice that Flaccus had the authority to give her what she wanted, turned to him. ‘I insist that my son be tested again. He’s only acting dumb.’ On the sheet she held up there were a dozen grids, each with five squares filled in, the rest blank. The pattern had to be recognised, replicated and, in later stages, elaborated. ‘He makes things like this out of his head. Tell him, Torbidda.’

Flaccus snapped the test from the woman’s hand and studied it for a moment. ‘You obviously understood the sequence up to the second line, so why did you put a five here?’

The boy looked down at the grids in bewilderment. ‘Was that wrong?’

Flaccus abruptly dropped into a crouch and grabbed the boy’s chin. As the Grand Selector looked at him – into him – Torbidda noticed his missing finger. It was an old wound, the stump worn rough.

‘You’ll have to do better to fool me, boy. I deal with liars every day, the best Concord has. Take the test again, and do it right, or your mother will end her days in the belly of the Beast. Don’t doubt my word.’

The woman began to cry and Torbidda shook his head as if deeply confused, as if there had been some terrible mistake. He looked at the man again, searching for sympathy. Finding none, he acknowledged defeat with a stoic sigh and leaned down on the examiner’s desk. He filled in the grid without pausing and handed it to Flaccus.

The Grand Selector scanned it and said quietly, ‘Give me the last sheet.’

Hiding his scepticism – no child ever got that far – the examiner fumbled for the form.

Flaccus pointed in the final box on the final row. ‘What goes here?’

Torbidda scanned the first row and paused a moment. Then he said, ‘Don’t you know, Grand Selector?’

‘I am asking the question,’ he growled ominously.

‘Sixty,’ Torbidda said.

‘Pay the woman,’ said Flaccus as he pulled Torbidda away. The boy turned to call to his mother, but her attention was rapt on the money the examiner was counting out, her grief and her son, the object sold, already forgotten.

Flaccus steered him uphill, his grip firm on Torbidda’s shoulder. For want of anything pleasant to consider, Torbidda pondered the Grand Selector’s absent finger. Amputation was a severe punishment, marking engineers with the stamp of civilian incompetence. The first lesson of Concord’s assembly line was that its blades were always thirsty; his generation needed only to examine their parents to see the savage surgery the engines could inflict.

They were soon in the highest part of Old Town, where the little wooden houses of civilians were replaced by tall stone buildings with taller stacks belching smoke and steam, all surrounding the base of Monte Nero, the rock upon which Bernoulli had planted his great triple-domed cathedral.

Flaccus stopped and looked down at the boy. ‘What’s your game?’ he asked, sounding genuinely puzzled. ‘Most Old Towners would kill to join the Guild. There’s third-year Cadets who couldn’t get to page four of the al-Buni, but I believe you found it easy. You really don’t want to be an engineer?’

‘I’d prefer to be free.’

Flaccus chuckled heartily at this and relaxed. ‘Not even the Apprentices are free, boy. Only the dead. But let me make this clear: if you give less than your best from here on, then I’ll make sure you get what you wish for.’

He left Torbidda in a pen with a dozen other children – despite what Flaccus had said, none of them looked happier than Torbidda about being selected.

As Torbidda took his place in the queue, the tall boy in front turned around to examine him. ‘Hello,’ he said cheerily. ‘How did you do in your al-Buni? Bloody hard, wasn’t it?’ His simple, well-cut clothes spoke of wealth as eloquently as his New City accent. His dark complexion was not uncommon amongst the aristocracy; most likely one of his ancestors had been in Oltremare long enough to take a native wife – many Crusaders had returned with their bloodline spiced with some of that Ebionite warrior prowess.

When Torbidda kept silent, his eyes fixed on the ground, the boy shrugged and turned back.

Torbidda looked up slowly and studied the back of the boy’s head. Then he examined the tall girl holding a clipboard at the head of the queue. A weeping blond boy entered the pen and she directed him to wait behind Torbidda. She was older than the other children, perhaps ten or eleven, and had the composure of an adult. She wore a Cadet’s white gown, with its distinctive wide neck and shapeless cut. Her hair was dark like his mother’s, but very short, almost patchy. She dealt with the inductees with a brusque confidence he found impressive.

After some time Flaccus reappeared and pushed another boy, heavyset and scruffy, into the pen, then walked swiftly back towards the examination desks. This new boy stared furiously after the Grand Selector, as if debating whether to hurl an insult or a stone, before finally looking around at the girl, who pointed to the end of the queue. He walked with the lumbering shuffle of a pit-dog, and Torbidda realised he was a real city boy, the type who made the New City stairwells so dangerous; he probably ran along the partition walls and dropped down on unsuspecting ferrymen. He was probably an orphan who’d volunteered himself.

The city boy looked disdainfully at the sniffling blond child and barked, ‘Move!’ When the blond boy stood aside, he pushed ahead of Torbidda, growling, ‘You too.’

The Cadet calmly set down her clipboard and walked over to them. The city boy tensed, but she sounded quite relaxed as she spoke. ‘This will take all day unless everyone waits their turn.’

‘I don’t take orders—’ he started defiantly, but she stepped forward, planted one leg behind his and pushed his shoulders, hard. The boy went onto his back.

Before he could rise, her foot was on his neck. ‘You’ve all year to prove how hard you are – all you have to do today is wait in line. Do yourself a kindness.’

Without waiting for assent she released him and returned to her station. The city boy silently took his place at the end of the queue.

‘Best give second-years a wide berth,’ said the tall boy in front, as if Torbidda had asked his advice. His expression was sympathetic. ‘Sad about leaving your family?’

Torbidda saw he wasn’t going to give up. ‘Not really.’

The tall boy looked surprised, then said, ‘Yes, quite right, we’ll see them in a year. What’s to be scared about? Plenty of children have been through it all before.’

Torbidda eyed his inquisitor with suspicion. ‘So what happens next?’

‘We’ll get our numbers soon. We’re supposed to forget names – mine’s Leto, by the way.’ He lowered his voice. ‘Leto Spinther,’ he said in an undertone, as if he didn’t want to sound boastful.

Torbidda had heard of the Spinthers, of course. He didn’t offer his own name, but Leto dispelled any awkwardness by ignoring it and carrying on with his cheerful patter. ‘They’ll tell you engineers don’t have names – don’t you believe it. A third of the students here are from good families, even though most probably didn’t get to the second page of the test. The First Apprentice is an Argenti. That hardly slowed his climb up the mountain.’

‘I’m not from a good family.’

Leto had the tact not to laugh. ‘Don’t worry, there’s still perfect equality in the Guild. “No number greater than another”, as they say.’

Torbidda was bemused by such an innumerate statement from a prospective engineer; he didn’t get Leto’s courtly sarcasm. But he listened carefully, picking up the rhythms in Leto’s speech, cataloguing his words, sifting meaningless gossip from information that might prove useful, just as every other child in the pen was doing: working out the rules. Caution dictated that becoming friendly with any Cadet this early on would be premature – better to wait and size things up properly before committing; a bad alliance was worse than none – but this boy’s friendly, relaxed manner was obviously unfeigned, and with his family background …

‘I’m Torbidda,’ he said with a shy smile.

Leto beamed and shook his hand. ‘I got to the fourth page – mind you, this wasn’t my first attempt. My parents paid for tuition.’

The older girl made no small-talk as she processed the Cadets. ‘Take nothing that will slow you down,’ she instructed, and they obeyed, leaving behind bags and purses, even emptying their pockets. As Torbidda drew closer, he could see that a set of keys hung round her long neck instead of a Herod’s Sword. She had shadowed Grecian hair and olive skin that was more common further south of Concord; her robust features suggested she might even have some Rasenneisi blood.

After taking their details she pointed to the narrow stairway clinging to the side of the mountain and the children proceeded under a rusted arch that read Labor Vincit Omnia.

A few steps up and out of her sight, the city boy pushed in front of Torbidda, pausing only to give him a murderous look. Clearly he needed someone to blame for his humiliation and the girl was obviously not an option. Torbidda made a fist, but Leto said, ‘Not here. You’re liable to get yourself killed too.’

Torbidda ignored him and yanked on the city boy’s hood. The boy turned with it and pushed him, making Torbidda fall back, jolting down several slippery steps until he caught himself. Leto stood aside as the city boy climbed back down to where Torbidda was looking about in vain for a weapon, a loose rock, anything.

The city boy was about to pounce when he abruptly froze. ‘Catch you later,’ he said, then pushed by Leto.

Torbidda looked around for the reason for the boy’s retreat. The second-year girl was coming up the steps towards them. He held his arm out, but she walked over him. A few steps up she looked back and called, ‘Get up, Cadet! You’re on your own – haven’t you figured that out yet?’

Leto waited until she’d gone before helping Torbidda up. ‘I did warn you.’

‘You don’t believe in fighting?’

‘Not at the wrong moment. It’s an especially bad idea on terrain this bad, when the other fellow has the high ground and more experience in combat – well, street brawls anyhow.’

‘What should you do?’

‘Manoeuvre – make him surrender those advantages. Then attack.’

They climbed through rain that fell like whips, clinging to the slippery stone. Far below, Torbidda could see the factories of Old Town, wreathed in a perennial yellowed fog. The sheer number of factories wasn’t appreciable from below, but they worked night and day, engines churning out war engines just as the Guild Halls manufactured engineers.

The Guild might be brutally logical, but the buildings it inhabited were a monument of improvisation, hastily supplemented whenever needed. Though Monte Nero’s gradient afforded little level ground to build upon, there were extensions, and extra towers and outhouses perched wherever space could be found upon the great rock. The towers that originally housed the Molè’s builders were connected by iron bridges and narrow passages cut through the mountain itself. They were never meant to be permanent – they formed a strangely chaotic venue for training ordered minds – but proximity to the Molè trumped all other considerations. Now, the higher the building, the greater its importance.

A third of the way up, a particularly stout tower sat isolated on a little summit: the Selectors’ Tower, a hub to the surrounding minarets. As well as bridges and stairways, Torbidda could see a tangle of wires connecting each tower, like a web. He couldn’t begin to guess their purpose.

At the end of their climb the children dragged themselves, panting and perspiring despite the cold, under a second arch that read Homo Homini Lupus, where a long rectangular building dominated the space: the Cadets’ quarters. The baths were in a bunker below the building.

Following orders, the children hurriedly stripped and ran the gauntlet of pressured water jets that struck their skin like hail. Torbidda emerged from the dousing to discover his clothes gone. In their place was a ticket. Leto quickly whispered what was coming, and Torbidda tried to compose himself.

Baaa baaa—

Baaa baaa—

He listened to the gleeful jeering as he waited in line; it made him shiver more than the bitter wind on his wet, naked skin. As he entered the refectory he felt his face redden and his eyes water. Leto had a distant, small smile on his face, but he kept his head bowed. The city boy, still angry after his humiliation at the hands of a girl, was like a trapped animal, constantly looking about for a means of escape. Torbidda thought he was just making it worse for himself – this need only be endured. To distract himself, he studied the lectern at the top of the hall, a great silver eagle. Leto said edifying Bernoullian maxims were read out from here as Cadets took their meals, but today the new second-years were to be edified with a different spectacle.

Baaa baaa—

Baaa baaa—

The refectory echoed with the mocking calls. Torbidda caught the eye of the dark-haired girl for a moment. Although she wasn’t joining in with the taunting, she was watching proceedings with interest as she ate.

Three at a time, the new inmates were summoned to the top of the hall, where an ancient trio of bored-looking legionary barbers waited, grizzled antiques who probably fought at Montaperti.

‘Ticket. Sit.’ A mechanical exchange and a rough shearing. The message was clear: A bad job is good enough for you. Torbidda had always been able to distinguish between what adults said and what they meant; the two were generally at odds. This here – this methodically orchestrated spectacle with all the nakedness, the jeering, the renaming – it was an induction into a new family. If they were lambs, they were lambs without a shepherd, for this was an abattoir where children were efficiently ground up and recomposed as engineers.

When his hair was scattered on the ground, the wheezing old sot pressed a waxy piece of paper against his skull and braced his head with that hand as he took the hot knife in the other. Torbidda didn’t flinch, but he couldn’t stop the tears rolling down his cheek. Unfair, he thought, to pry out this evidence of weakness.

Pulling off the stencil, his shearer told him flatly, ‘Your name is’ – rippp! – ‘Sixty.’ He poured a foul-smelling orange oil onto to Torbidda’s head which burned as he rubbed it in. Cold drips streaked Torbidda’s neck and back. ‘Let the scabs heal by themselves. Stand and dress yourself, Cadet.’

He was finished just before the other two. The side of Leto’s head read LVIII and the stupefied city boy’s read LIX. Torbidda was walking away when he turned and glanced back as three new naked children took their place. Already he felt different. They were civilians. He was a Cadet, Cadet Number LX. His name was Sixty.

His mother screamed curses at the Grand Selector as they dragged him away. ‘My baby! Don’t take him from me, please!’

It was too unbelievable not to be a dream. Torbidda opened his eyes and listened instead to the storm outside the dormitory, and children weeping in the dark, weak islands adrift in a predatory archipelago. Other voices catcalled and teased, but no one ventured out of their cubicles. That first night was a period of watchful waiting, of study. Like an al-Buni grid, they had to learn the rules before advancing.

RATATATATATA TATTARATA TA TARA RAT AT AT AT T T T

The bell was the lambs’ first lesson: that belligerent mechanical rapping would henceforth marshal Cadets’ hours, dictating when to study, eat and bath; when to sleep and when to rise—

‘Let’s go, maggots! An engineer’s got to outpace the sun!’

The second-year who’d processed them yesterday was monitor today, and her first duty was to familiarise the lambs with early rising. ‘Anyone still sleeping when the bell rings tomorrow gets a visit to Flaccus’ tower. Next week, it’s automatic expulsion. That’s right: back to the mills. Back to mines. Back to the streets. You don’t want that, and I don’t care. Let’s go! Let’s go!’ Torbidda was learning already to distinguish between the babble of new accents; her broad singsong came from the Concordian contato.

The dormitory was a long, wide hall with a curved roof. Light beams from high circular windows crisscrossed the dusty space, making Torbidda think of the belly of an overturned ship. There were four rows of cubicles, with a corridor running alongside either wall and in the middle; the two doors were in opposite corners. Each cubicle had a single bed and a wardrobe, and a modicum of privacy was provided by thin blue curtains hanging from a steel bar. The back-to-back wardrobes formed a narrow walkway for adventurous midnight prowlings.

‘Keep Flaccus waiting down at the shooting course and he’s liable to use you for a target!’ the monitor shouted as the last of the lambs ran out. Somehow, Torbidda didn’t think she was making that one up.

Bernoulli, the Guild’s founder, had wanted his Cadets as deadly as possible, as quickly as possible. They would first be taught to use projectiles, including hand-cannons and bows, and then knives. Only those who survived the initial cull to become Candidates would learn the more sophisticated martial arts, which were more deadly than any weapon.

The lesson took place on the shooting course. The mountain face above the course was upwind from the factories, and pockmarked with craters. Though yesterday’s gales had ebbed somewhat, a misting rain obscured their targets – but Grand Selector Flaccus made no allowance for these difficulties. ‘Think the Forty-Seveners had your advantages?’ he drawled. ‘Conditions in battle aren’t always favourable, Cadets.’

By the day’s end, their brains would be exhausted from calculating arcs and rates of descent, their eyes and throats raw from the gunpowder and their fingertips bleeding from plucking bowstrings – but everyone’s aim would have improved. Flaccus was an impatient, harassing tutor, and the Cadets were soon grumbling, and taking revenge by making up increasingly fanciful reasons for his missing finger, from condottieri proof-of-life to the Guild’s punishment for incompetence. Leto said Flaccus was a field commander who had lost his first command, and the Guild had had to pay his ransom; teaching Cadets was his demotion.

‘For which he’s determined to make us pay,’ Torbidda said grimly.

Although Leto couldn’t match Torbidda’s speed at calculating distances and gradients – none of them could – he proved to be an adept archer. Leto had grown up on the Europan frontier, in the legionary camps commanded by his famous father, Manius Spinther. Most of the aristocracy lucky enough to survive the Re-Formation held onto their empty titles until their purses were empty too, but the Spinthers were different; they adapted to the changing times. While Bernoulli’s star was rising, various prominent Spinthers renounced their titles and sent their sons off to learn the mechanical arts, and when the storm came, they escaped the worst ravages of the mob – by being part of that mob. ‘Engineers have no family,’ Leto liked to say, ‘but a Spinther is always a Spinther.’ His cousins had all been through the Guild Halls and now it was his turn. Torbidda, perceiving that Leto’s first loyalty was to family, stored that away and counted himself lucky to have found such an ally.

He was clumsily nocking an arrow when Leto whispered, ‘Torbidda, look! That’s Filippo Argenti!’

Flaccus was whispering deferentially to the newcomer, a stolid, middle-aged man with the blank, weatherbeaten face of a mason. The vivid red of the First Apprentice’s gown looked unreal against the scarred landscape of the firing range. Others began to notice his presence and soon every Cadet was hitting wide of the mark – all except Leto, who continued to hit bulls’-eyes with perfect nonchalance. After watching for a few minutes, the First Apprentice clapped his hands and walked onto the firing range. The Cadets immediately lowered their weapons.

‘I need a volunteer. Someone willing to shoot me. Anyone?’ He paused, then sighed with theatrical relief when none stepped forward. ‘Well, that’s gratifying.’

Laughter dispelled the tension still remaining from yesterday’s induction.

Argenti looked around, and then started, ‘Brothers and sisters, welcome. I once stood where you stand. You’re asking, will I make it?’ He looked from face to face, nodding as if to say this was quite natural. ‘I won’t lie, some of you won’t. First year will be tough, but just remember that you’re not alone. If the Guild seems cruel, remember: it is not senselessly cruel. We winnow with reason. We need the best.’

He looked up at the brutalised crags behind the range. ‘The Guild is a mountain with many peaks – Old Town, New City, the Guild Halls – but really, they are one. Our strength is our unity. What is our strength?’

‘Unity,’ came the eager response.

‘Just so. Unity depends on team spirit. No tower can stand with each brick vying to be higher than the others.’

He stopped in front of Torbidda. ‘Each must be content in its place. The mortar that binds them must be—’

‘Trust?’ said Torbidda in a dry whisper. He felt Leto’s unease.

‘Trust! Exactly. I am First Apprentice not because I learned how to climb, but because I learned how to trust. It’s all very well to say so; you need to see it.’ Like a cheap magician he produced a small red apple from his sleeve and looked around brightly. ‘I need a volunteer. Whom can I tempt?’

Leto subtly shook his head, but the warning was unnecessary; Torbidda had already spotted Flaccus’ ill-concealed eagerness. The boy who’d been crying in the queue yesterday put his hand up.

The First Apprentice smiled kindly. ‘What’s your name, son?’

The blond boy had to think for a moment. ‘… Forty-Two, First Apprentice.’

‘Not your number. Don’t you have a real name?’

‘Oh! Yes, First Apprentice. Calpurnius Glabrio.’

‘Well, Calpurnius, I am a decent shot, and I need a volunteer.’

‘What must I do?’

‘That’s the spirit. Step up to the target. Place this on your head.’ There was an intake of breath and the Apprentice said in a loud voice, ‘Go back if you’re afraid. There’s no shame in it.’

Calpurnius solemnly took the apple and walked up to the target. ‘I trust you, First Apprentice.’

The Apprentice took careful aim and released. The arrow took the apple with a wet thunk-kuh-kuh. Calpurnius joined in the applause. Quickly, the Apprentice nocked another and shot again. The force drove Calpurnius back and pinned him against the target.

As the boy screamed, the Apprentice turned around. ‘Why have you stopped applauding, children?’

He looked back at Calpurnius, took another arrow, drew back and released. The screaming stopped. ‘What are you thinking now, Cadets?’ he snarled. ‘That this was unfair? I tell you: it is necessary. The Guild is an army, and an army is only as strong as its weakest member. You’re here because you’re clever, so I won’t patronise you. We take you young, when it is still possible to change you – to mould you. You have begun to climb the mountain, and now the only way out is up. Your peers will not help you. They will do everything to make you stumble. Each summit is further up, and the higher you go, the purer the competition – and the further to fall. There’s no safety down here, either. Believe me, the laggard will quickly find himself without allies.’ This time his smile was sour and weary. ‘As you climb higher, you’ll appreciate that we Apprentices are not to be envied. Having reached that final peak, we can only watch as our competition surrounds us. But that’ – he looked around with hostility – ‘is as it should be.’

He turned once more to Torbidda. ‘You, boy: what is your name?’

‘Sixty, sir.’

He smiled kindly. ‘I mean your real name.’

‘Sixty, sir.’

The smile disappeared. ‘Fetch me that apple, Sixty.’

‘No, sir.’

‘That’s the correct answer.’ The Apprentice turned and walked over to the target. ‘You will hear talk of factions: engineers against nobles, Empiricists against Naturalists. Ignore these chimeras. All alliances are temporary. Your competition is all around you. Make alliances, by all means, but know this: all friends must eventually become rivals.’ He pulled out the arrow and removed the apple. ‘Calpurnius wanted to be loved. You must rise above that temptation.’

‘This’ – he threw the apple to Torbidda – ‘is for saying no to me.’

As Torbidda caught the apple, the First Apprentice’s fist moved.

After a moment’s numbness, sharp pain spread throughout Torbidda’s chest. He sat up and coughed blood. He was several braccia from where he had been standing. Every Cadet was staring open-mouthed. The man in red looked down at him. ‘And that is for not shooting me when you had me in your sights. I wait for you, all of you. Come and cut my throat someday.’

Torbidda watched the First Apprentice walk slowly back to the Guild Halls, wondering how, if that day ever came, he would find the courage to do it.

First Apprentice Argenti’s demonstration had left Grand Selector Flaccus almost giddy. ‘That’s what it’s all about, Cadets,’ he huffed with admiration. ‘Man domesticated himself along with the dog. We must be wolves again.’

One of the Cadets threw up, and Flaccus snatched Torbidda’s apple and threw it at him viciously. ‘What did you expect? The Guild is not the Curia. The Guild Hall is not a seminary. Don’t start feeling sorry for yourself. You’re receiving an unrivalled education at great cost to the State. Some say war’s a cheaper and better school for engineers; some say it’s wasteful to educate so many when so few of you will survive …’ Flaccus obviously shared this view. ‘… but the Colours say waste’s inevitable when mining. They want the best, and the best are those who survive. All right, break’s over. Back in line.’

As they reassembled, Torbidda caught the eye of the boy who’d vomited. The boy blushed in anger as he wiped his mouth. He stood shoulder to shoulder with the others and nocked an arrow. Torbidda looked away and did likewise.

‘Take aim—’ Flaccus roared.

Argenti’s demonstration had strange results on the children. While some became cautious, others took it as licence to indulge all their passions unrestrainedly. That night the city boy, Fifth-Nine, cornered Torbidda in his cubicle. Three other city boys joined in, while a fourth stood at the curtain, watching proceedings. The onlooker was the boy who had caught Torbidda staring. When he said, ‘Enough!’ they stopped. He was handsome, and had a New City accent like Leto’s.

Curtains had to be drawn in the morning to display tidy cubicle, locked wardrobe and neatly made bed. Torbidda was just pulling his open when the monitor walked by. She must have seen his black eye, but all she remarked on was his tardiness: ‘Do better, Sixty. It gets faster.’

And she was right. Those who made it would be landed on the front line,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...