- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

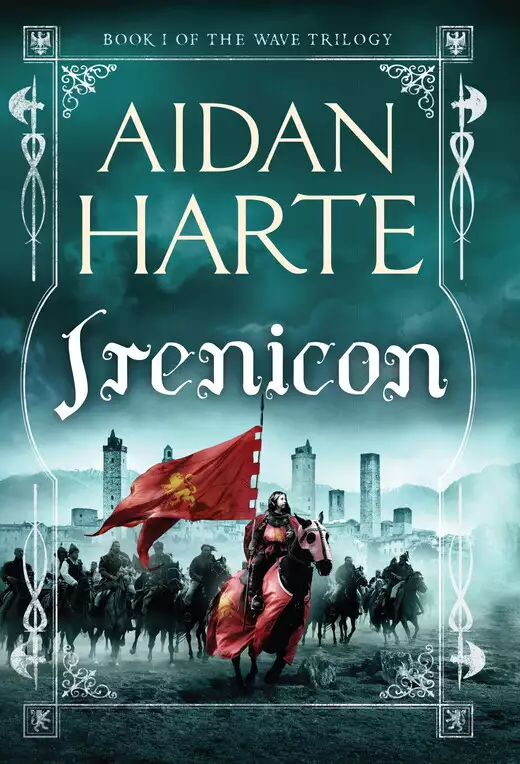

' Irenicon is completely fascinating' - Thinking About Books The river Irenicon is a feat of Concordian engineering. Blasted through the middle of Rasenna in 1347 using Wave technology, it divided the only city strong enough to defeat the Concordian Empire. But no one could have predicted it would become sentient, and hostile. Sofia Scaligeri, the soon-to-be Contessa of Rasenna, is inheriting a city tearing itself apart from the inside. She can see no way of stopping Rasenna's culture of vendetta . . . until a Concordian engineer arrives to build a bridge over the Irenicon. He shows her that the feuding factions of Rasenna can continue to fight each other, or they can unite against Concord. And they will need to stand together - for Concord is about to unleash the Wave again . . . Set in a darkly original alternative Renaissance Italy, Irenicon is a gripping adventure, a tragic love story and a very modern tale of redemption.

Release date: March 29, 2012

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 402

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Irenicon

Aidan Harte

Madonna! Where was he?

If the boy got hurt, the Doc would mount her head on a stick next to the Bardini banner. Valerius might be a handful but the little stronzo was their only Contract this year. Besides, a dead Concordian would imperil all Rasenna. Sofia’s dark eyes flashed with anger and she swore again: in her haste she had forgotten her banner. Being unarmed in Rasenna used to be merely careless. These days, it was suicidal.

Valerius ran down the sloping streets with his head in the air, pursued by his shadow made strangely large by the blood-washed light. Smashed roof-slates crunched underfoot like leaves in an autumn forest. He followed the trail of the topside battle as it moved downhill towards the river, focused on the jagged red slash of evening where the towers leaned towards each other across the emptiness.

The Concordian had the pale blond curls, soft skin and, when he tried, the disarming innocence of a cherub. Now, scowling, he resembled something fallen and impious. Sofia, only five years older than Valerius, watched him like his mother. He had endured this ordeal since his arrival last Assumption, but to return to Concord unblooded? Ridiculous.

The hunt was practically the whole point of a year in Rasenna – that was what his father had paid for, not endless drills and lectures on banner technique. So when this chance came to sneak out, Valerius took it, vowing to get the General’s money’s worth. Two households in combat: what a story! This was Rasenna’s real meat: raids and rogue bandieratori. He wasn’t in real danger; this was still Bardini territory. Sofia wouldn’t be far away.

He couldn’t see the individuals leaping between rooftops, just the banners they wielded. Bardini black outnumbered Morello gold four to six, and the Morello were retreating – noisily. These boys weren’t bandieratori, they were like him, just bored students looking for fun. So it was an unofficial raid, then; the gonfaloniere would never sanction such a pointless attack.

Valerius followed through one backstreet after another, concerned only with keeping up. A black flag vanished behind a corner. He turned it himself and saw nothing but swallows listlessly drifting on air rising from the empty streets.

No Morello, thankfully. No Bardini either. Valerius stopped to listen. The wall he leaned against was built around the ghost of an Etruscan arch, the gaps between its massive blocks stuffed with crude clay bricks, bulging like an old man’s teeth.

He could hear the river now, but not the battle. He had been in Rasenna long enough to know that most raids ended ‘wet’. How could so many raiders disperse so swiftly? It began to dawn on him that Bardini flags need not be wielded by Bardini.

How could Sofia be so irresponsible? He was the Bardini Contract, the Bardini’s only Concordian student, and that made him an obvious target for the Morellos; he should be protected at all times. The General would hear of this.

‘Keep calm, Concordian,’ he rebuked himself, just as the General would have. He knew northern streets pretty well after a year, didn’t he? Not like a Rasenneisi, not as lice know the cracks, but well enough. He looked for clues to his location. That ceramic Madonna, perched in a streetcorner niche and drenched in blue-white glaze, that would orientate a Rasenneisi. The ghastly things all looked the same. The superstitions of Rasenna were not the answer; he would rely on Concordian logic. The raiders had led him down and south. If he followed the slope up he would eventually reach the shadow of Tower Bardini and safety.

He turned around. Now he had a plan it was easier to fight the urge to run for it. Yes: he was impressed with his courage, even if he did keep glancing overhead. If only his footsteps wouldn’t echo so.

At last, something familiar: the unmistakable drunkentilt of Tower Ghiberti – the Bardini workshop was close after all. Valerius’ relieved laughter trailed off when a rooftop shadow moved. Another silhouette emerged on the neighbouring row. And another. Lining the tower tops, above and ahead of him. He counted seven, eight, nine – a decina – but forced himself to keeping walking. Whoever they were, they were interested in him alone. It was not a flattering sort of attention.

Behind him someone landed on the ground and he was torn between two bad choices, to turn defiantly, or to run.

‘Walk.’

‘Sofia! What are you doing?’

‘Exceeding my brief. Doc said babysit. He didn’t mention stopping you getting yourself killed.’

‘I wouldn’t be in danger if—’

‘I said keep walking!’

He whipped his head round to continue the argument, but went suddenly mute. Anger enhanced the Contessa’s beauty. Her dark eyes were wide and bright, her olive skin glowed like fire about to burn. She looked fabulous just before a fight.

‘What do we do?’ Valerius asked, his confidence returning.

Her wide-shouldered jacket was a bold red, in contrast with the earthy colours favoured by most bandieratori. She was not tall, but she held her head proudly. Below her large brow and sharp Scaligeri nose were the smiling lips that graced statues of cruel old Etruscans.

But she was not smiling now and her pointed chin jutted forward. ‘You’ll do as I say. I’m going to help these gentlemen get home. Give me your banner.’

‘I don’t have it,’ Valerius whispered, losing hope again.

‘Madonna. This is going to be embarrassing. I’m not exactly in peak condition.’

Valerius looked down at the sling on her arm. Without a single banner, against a decina, even Sofia …

‘What do we do?’

‘When I say run, run – Run!’

Sofia led the way through the maze of narrow alleys, not looking back or up. She knew by fleeting shadows overhead and loosened slates smashing around them how closely they were pursued. She skidded to a stop when they reached Piazzetta Fontana. The alley leading north was blocked by five young men. And now Valerius saw what Sofia already knew: they were not students. They were bandieratori. Their ruckus had been part of the deception.

Sofia pushed Valerius into an alley on the right – it was barely a crack between two towers, but it led north.

‘Run. Don’t look back.’

He didn’t argue.

She boldly stepped forward. ‘You bambini must be lost in the woods. You’re on the wrong side of the river.’

There was consternation as the southsiders saw who they had been chasing. ‘What do we do?’ asked one.

‘Her flag’s black. That makes her Bardini,’ said the tallest boy with assurance.

‘I don’t know – if Gaetano—’

‘Show some salt! There’s one of her and lots of us. Haven’t you heard who broke her arm?’ The tall boy continued talking even as he approached her. ‘She’s hasn’t even got a flag—’

Way too casual. Sofia was ready. She dodged his lunging banner and snatched it away in one movement and his jaw had no time to drop before she floored him with a neat parietal-tap. By the time she looked up the others had vanished, gone to get Valerius before she got them. Sofia returned to the narrow alley and vaulted left-right-left up between the walls.

Etrurians said that Rasenna’s towers were different heights because not even the local masons could agree. But they made good climbing, and bandieratori jumped between towers as easily as civilians climbed stairways. The upper storeys were peppered with shallow brick-holes, invisible from the ground, which had originally supported scaffolding but which now allowed the fighters to scale what they couldn’t jump.

With only one working arm, Sofia knew her climbing was awkward and inefficient. Even so, when she made topside she took a moment to catch her breath and scan the endless red roofs, feeling no need to hurry despite their head-start. This was her territory, and she knew every roof, every crumbling wall. They did not, and in the wan light of dusk they’d have to be cautious.

In the heat of the chase the boys let one of their number fall behind, and it wasn’t long before Sofia caught up. His falling scream was cut off by the crash of broken slates.

Two down, out-classed on strange rooftops. Normally in this situation it would be each raider for themselves, but these three knew that their only hope of ever getting home was to regroup and turn and fight together. They were waiting on the next tower Sofia leapt for, and gave her no time to recover her balance. Two of them launched a noisy attack to make her retreat, while the third slipped behind. As Sofia dodged flags she was struck in the back of her knee.

‘Ahh!’ she cried as she landed on her back, sliding a little before halting herself. She had no time to rise before she felt a flag-stick prodding against her neck. She lay still before the pressure crushed her larynx.

‘Beg your pardon, Contessa.’

Sofia ignored their giggling. She still had the advantage. She knew every tower bottom to top, their flags, the fastest routes, how old they were. She kicked her heel and a slate came loose, then several fell in its wake and the tower shed its skin with a shudder that drowned out the boys’ shouts as they all slid and tumbled together. Sofia went over the side with the rest of them, but she reached out and grabbed the unseen flagpole. She didn’t look down. No need.

She heard them land with the slates, breaking all together.

Sofia hauled herself onto the flayed rooftop, then climbed back down. She found Valerius waiting streetside with an amused expression on his face which, like his clothes, was splashed with blood. The boys’ bodies lay where they’d fallen, perfectly arranged in a semi-circle around him as if hunting him even in death.

‘Where’s the rest?’ she asked, more to herself than Valerius. She had been occupied, yet the others hadn’t gone for the Concordian. Wasn’t he the prize?

Valerius ignored her, more interested in rolling the corpses to see their last expressions.

‘Show some respect!’ she snapped. ‘The dead are forgiven.’

‘Sorry!’

‘Come here,’ she said, pulling Valerius towards her.

‘Oh Sofia, I was frightened too!’

She pushed his embrace aside roughly. ‘I’m checking for wounds, cretino!’

But no, none of the blood was his. Doc’s charge was intact, the Contract secure. ‘You got blooded, Valerius. Satisfied?’

It was a blade-sharp February, but this winter’s night the alleys around the workshop were ablaze with torches. Groups of Bardini bandieratori gathered on the corners, banners up, tense and jumpy. Sofia nodded to a tall young man slouching against a wall, his hood pulled low. The other boys intended to keep darkness at bay with a constant uproar, but Mule contented himself with silence. A flat-faced boy, he had a drooping eyelid that suited his sleepy air. Nobody had ever called him stubborn, and that was enough in Rasenna to earn him his nickname.

‘What’s got so many flags out?’

‘Burn-out,’ he said. ‘Ghiberti’s.’

Sofia saw the ruse now and swore. ‘We going over tonight?’

Mule shrugged. ‘Check in with the Doc. He was worried about you.’

‘He was worried about Payday here,’ said Sofia, angrily pushing Valerius forward. ‘Move it, will you?’

She led him to Tower Bardini. Black flags bobbed aimlessly around the base of its ladder. The single calm face in the crowd looked up. With no neck to speak of, the Doctor’s bald head hardly broke the hill of his shoulders. He made no large gesture when he saw her, just raised his eyebrows. Sofia nodded back and pulled Valerius out from behind her. When he saw the Concordian, the Doctor paled.

Sofia patted Valerius’ cheek and held up a blood-smeared hand. ‘Don’t worry, Doc. It’s not his.’

‘Are we safe now?’ Valerius asked.

She nodded briefly, keeping her eye on the Doctor’s reaction as he approached.

Valerius stepped forward and slapped her. ‘Show me some respect!’

The Doctor leaned forward and grabbed Sofia’s arm before she could strike back.

Valerius stuck a finger in her face. ‘Noble or not, you’re still just a Rasenneisi!’

The Doctor put his sturdy frame in between them. ‘We apologise, my Lord. My ward forgot her place through her zeal to protect you.’ His fingers tightened around her arm. ‘Right, Sofia?’

‘Right,’ Sofia managed through clenched teeth.

Valerius looked sour for a moment, then nodded. ‘Fine. I’m hungry after all that. Doctor?’

The Doctor released Sofia and bowed to Valerius. ‘I shall await you.’

Valerius watched him leave, then turned, smiling, to Sofia, the guiltless cherub once more. ‘I thank you for saving me, Contessa,’ he said stiffly and then, lowering his voice, ‘Look, sorry I had to do that. Concord’s dignity—’

‘Demands no less,’ Sofia said. ‘No apologies but mine are necessary, my Lord.’

‘Oh, Sofia! Don’t be so formal. Let’s be friends again,’ he said, and leaned forward to kiss her cheek.

She watched him scurry up the tower’s ladder. Had he stayed, he would have recognised the glow surrounding her. It was not her throbbing arm that had made her angry – and not even Valerius; the Concordian was acting properly, in his own way. It was the Doc, and that she was party to his appeasement. Distrusting herself around either of them, she decided to retire to the Lion’s Fountain. Mule and his brother were probably at the tavern already. The smoke of another burn-out tasted bad in every mouth. First, though, she grabbed a workshop flag. It wouldn’t do for the Contessa to be caught unarmed twice in one day.

Etruria was wrong: the Concordian Empire did possess a heart, of sorts. It was this unsleeping place of greasepumping clockwork pistons. The final dome crowning the Molè Bernoulli had been dubbed the engine-room by ordinary engineers like Captain Giovanni, although ordinary engineers were rarely privileged to see it – or, indeed, to be personally briefed by the Apprentices. Giovanni did not rejoice to be so favoured, for he knew it was a curse.

Giovanni wore sober black like every other engineer. Only the Apprentices wore the long coloured vestments of the supplanted cardinals. Even so, the Third and Second Apprentices were shades in the darkness. Only the First Apprentice was entitled to wear the true colour, a red so vivid it seemed to emanate from a burning interior.

‘Rasenna?’ said Giovanni.

‘You think the posting beneath you?’

‘No, my Lord.’

‘We are all heirs to Girolamo Bernoulli. You are not special.’

‘I know that, my Lord.’

‘Captain, I will not dissemble. You’re a disappointment.’ The First Apprentice raised his hands as if he had been interrupted, though Giovanni kept his head lowered, letting his unruly dark hair hide his eyes as he struggled to control the restless muscles of his broad face.

‘You showed promise once. You performed a service that shall be remembered, once. Since then?’

‘I follow orders.’

‘Oh, you have an engineer’s obedience, no one questions that. We question your enthusiasm.’

A man’s voice behind Giovanni said, ‘Rasenna’s ambassador is waiting, my Lord.’

‘Let him wait, General!’ the First Apprentice snapped.

He was tall, and his sorrowful face had severe high cheeks and a tragic composure disturbed by neither joy nor wrath. He spread his arms, letting his long sleeves fall open, and looked on Giovanni. ‘Captain, as different as they were, your father and grandfather had something in common: conviction. Show some. Be an engineer, or be a traitor. Do not be lukewarm. Nature abhors it. We abhor it.’

‘Yes, my Lord.’

‘We would advise you to make Rasenna fear you, but we suspect you are too lukewarm to do even that. We shall see to it.’

Giovanni looked up suddenly.

The First Apprentice was pleased to have pierced his feigned apathy. ‘The Rasenneisi ambassador expects to deliver our message. He will be our message.’

‘Please, my Lord, it’s unnecessary—’

‘I am the First Apprentice of Concord, Girolamo Bernoulli’s true heir. Do not lecture me on necessity.’

‘Forgive me,’ Giovanni said quickly.

The First Apprentice nodded, though whether satisfied or just signalling silence, Giovanni could not tell.

‘Rasenna no longer matters, but it appears destined always to stand in our way, if now only in a physical sense. Its position is key in the coming campaign. It must be ready before we send the Twelfth Legion south. You have the State’s resources at your disposal. If cooperation requires soldiers, send for them.’

‘That won’t be—’

‘Necessary?’

Giovanni looked down and said nothing.

‘Well, we shall see. If we expected your work to be difficult, we would send someone who had our fullest confidence. Possibilities outweigh the certainties of this world, but some things we may count upon: towers fall, smoke rises and Rasenneisi quarrel. Use them. If you fail, it won’t be your delicate conscience to suffer, but Rasenna. Send up the ambassador on your way out. We dismiss you.’

Giovanni didn’t move. He was looking at his hands, remembering what deeds they’d done in Bernoulli’s name.

‘You may go, Captain,’ the First Apprentice repeated.

‘They’ve suffered enough,’ Giovanni said quietly.

‘Suffered enough?’

At the far end of the engine-room there was a screech of chalk as the other Apprentices stopped their work.

‘Suffered enough?’ The First Apprentice repeated the queer word pairing, and his colleagues in the dark chuckled.

Giovanni lifted his eyes to meet the First Apprentice’s – a small act taking great effort.

‘Oh, Captain,’ the First Apprentice said wistfully, ‘there is no limit.’

It was a curiously unpleasant smile for an angel. The statue’s colossal body glowed in the intersecting shafts of light. Bowing to read the Low-Etruscan motto inscribed in the base, the ambassador was covered by its shadow. ‘Eadem mutata resurgo,’ he mumbled, and translated, ‘Although changed, I shall arise the same.’

Valentino was pleased to display his erudition, if only to himself. He was far from home and did not belong. He had been abandoned in the great hall of soaring pillars. The pillar in the centre was thicker than the others, and made of glass that was dappled inside with pale green fugitive gleamings. Did every ambassador receive this treatment, or just Rasenna’s? In their place he would do the same, so he could not resent it. Much.

He looked around while using his sleeve to rub the chains of office that stubbornly refused to shine. He was still glad his father had appointed him. The old fool had only agreed when persuaded that the prestige outweighed the danger. The problem as ever was money – another bad year, and Rasenna could not raise its tribute. Such fuss over such a small problem, with such an obvious solution. He would beg. The Empire had larger concerns than one insignificant town.

Valentino retreated from the colossus. In a gleaming breastplate he was pleased to find not some unremarkable boy looking back, but an elegant young diplomat. He passed a happy minute admiring his dignity, growing confident. Whatever they called themselves in their vulgar dialect, the Apprentices were Concord’s élite just as the Morello were Rasenna’s. Ultimately, they spoke the same language.

A distant large sound of great metal plates scraping off each other made Valentino scurry back into the shadow of the colossus. They would discover him there, lost in aesthetic reverence. His gaze was drawn up the column to a point of pure white in the distant darkness. The great dome seemed large as Heaven, and something was falling fast, emitting a whine that grew louder by the second. He yelped as the column began filling with water, the level rising to meet the star. The large coffin-shaped capsule cushioned on the water came to a stop. Valentino expected an Apprentice to emerge, not yet another engineer functionary, but he masked his annoyance with a smile and began his speech: ‘Just admiring—’

The engineer broke free of the old soldier flanking him and grabbed Valentino’s outstretched arm. ‘Ride from Concord tonight,’ he whispered fiercely.

‘I don’t understand—’

‘Say you must return to Rasenna. An emergency. Say anything. You don’t belong here.’

Valentino snatched his arm away. ‘I came to see the Apprentices. I shall not leave before that meeting.’

A heavy hand on his shoulder. ‘Ambassador,’ the general said, ‘the Apprentices are waiting. You have your orders, Captain. Give Doctor Bardini my regards.’

Giovanni looked on helplessly as the ambassador was led away. Valentino gave the colossus a parting glance, discerning too late that it was smiling derisively.

North of the trespassing river, dawn crept on cat-paws over Rasenna’s briefly golden towers, clustering sheepishly in the long shadow of Tower Bardini. To one illiterate in the language of banners – in a word, foreign – Tower Bardini could only be recognised by the small orange trees on its roof. Every morning the Doctor sat there for an hour, tearing oranges in two and watching over Rasenna.

His half.

The older generation of Rasenneisi permitted themselves only essentials, so the Doctor’s sleep was undisturbed by dreams. He had still passed the night brooding on Sofia’s narrow escape, making careful plans and tearing them apart. He had raised Sofia like a daughter, but he remained clear-sighted: custody of the Scaligeri heir gave the Bardini what passed for legitimacy these days, a damp seat in the Signoria. Yesterday’s target was not Valerius.

Scratching and stretching himself awake, the Doctor ambled down the wooden stair winding round the bare stone walls. A big man, and wide, he took his time in all things, confident in his strength if called upon. His thick arms and neck were covered with a downy thickness more like animal fur than hair. He wore wide, loose breeches tied up around the middle of his chest where his shirt opened, and over all wore a gown that had once been heavy; time had exhausted the colour too; it had once been the deepest of blues. The long sleeves were torn in places, but most of the time they covered his large callused hands which hung low when he walked, as if the knuckles carried some extra weight. His nose, broken and rebroken many times, was large and fleshy, and his cat’s smile stretched wide across a heavy chin, dark with permanent stubble.

Every tower was drably similar inside, no matter what generous colours hung outside, and like a castle keep the door was never on the ground floor; a ladder was lowered for visitors. The Rasenneisi preoccupation with security told in other ways too: friendly families built towers close enough to be connected with rope webs but of course nothing as permanent as a bridge. Ropes could be cut. Alliances could break.

He knocked on the third-floor door. No answer. He glanced inside. His shrewd eyes hid behind a squint merry as an old pig’s, and just as cruel. He slammed the door and with quickened pace, muttering curses, crossed the walkway to a plain wooden building, hearing laughter from below as he entered. The workshop was as low and wide as the towers were high and narrow – it contained a small army, so needed no such precautions.

The students were gathered in one corner of the long hall. Sofia’s dark hair shone out in the midst of all those shaven heads. She had a firm hand on Mule’s shoulder, and she was laughing too. The Doctor ignored the laughter, but he noticed both Mule’s bandage and the rosy patch where an ear should be. He followed a trail of cherry drops in the wood chippings on the floor as he worked out what had happened.

‘Morning, Doc! Mule volunteered to teach us first-aid.’ There was laughter in Sofia’s voice, but he caught the look she flashed him and returned an affirmative grunt.

She continued her story: ‘So, I got home late – pretty drunk, I suppose, ’cause I crashed in the workshop. Just before dawn, I wake up to this horrific snoring – you can’t imagine! Some drunk, I figure, napping on the Bardini doorstep—’ Sofia stood with one arm on her hip, managing a good impression of a house-proud mama despite her sling. ‘Of course, I’m outraged!’

The boys were rapt, and the Doctor knew that this was more than the respect commanded by her name. It was love. The Scaligeri inspired it effortlessly, and it had been their greatest asset – their enemies hated them for it. Sofia never braided her hair in complicated patterns, nor did she pluck her eyebrows, or apply perfumes, or powder her luminous olive skin. Though she dressed as other bandieratori did, doublet and hose, jacket and cap, she did not look boyish, yet she could show an arm without embarrassment or ceremony because one did not compare the Contessa to other girls. The Contessa was something apart, as far from the ordinary run of humanity as the statues in the alcoves.

This last year something had changed. She’d tried hiding in different ways – her fringe hanging over those dark bright eyes, the street-fighter’s sun-muddied complexion, elbow and knuckle-scrapes proudly displayed – but it wasn’t enough. A million other things said it: her belt, slung low on her hips, the tilt of her cap, the way she didn’t sing any more. After a lifetime looking for weakness he always saw the things people tried to hide, and he knew the workshop saw it too. When had it happened? What moment? He guessed it happened the way spring turns to summer, the way fighters become killers. You only knew after the event.

‘We’ll see about this, I say—’

Mule interrupted, ‘Last thing I remember was running down Purgatorio after Secondo, then I turned into Penitito and Secondo was gone—’

‘I thought you were behind me,’ Secondo snapped.

Sofia had never had to break a sweat, but the Borselinno brothers had become capodecini the hard way. They were equally tall and thin, and they started identical, but years of fighting had deformed each uniquely. Mule took life as he took this injury, with an easy laugh, but Secondo found disrespect where none was intended and had creased his young face with frowns and vexation. Even now he was holding himself stiffly above the general laughter.

The Doctor could see where the story was going. Purgatorio, Penitito – those streets were south of the Irenicon. After the burn-out, the Borselinno boys had taken the Midnight Road. Their bad intentions were good; a burn-out demanded reprisal.

The Doctor walked to the workshop door and opened it.

Sofia continued, ‘Obviously some Morello hero got the drop on genius-boy, but what I can’t figure out is how you can sleep nailed to a door.’

‘They gagged me!’ Mule said.

‘You didn’t think to knock?’ She punched his arm before turning to her audience. ‘So I yank open the door and scream, “You know what time it is?”’ She paused for a moment, then, ‘Riiipp!!’

Mule was now helpless with laughter.

‘There’s blood spraying everywhere! I get a face-full. I ungagged this deficiente. He looks at me all innocent, and says, “What you wake me for? I was dreaming!”’

‘I was!’

The Doctor tore the cold meat off the door then slammed it. ‘Basta, bambini. Story-time’s over.’

The circle broke up and reassembled into classes. The intermediates had just gone from sticks to flags and it showed. The Doctor looked at Sofia, unsurprised to find her unsmiling now the audience had dispersed. The incident was nothing to laugh at – her performance had been for the novices. Boys needed to acquire a casual attitude to spilled blood.

The Doctor divided his bandieratori, those young men who needed no instruction, into sparring pairs, before discreetly approaching Mule. The injured fighter was sitting quietly on the stairs with a dazed smile.

‘Want this back?’

‘Naw, Doc. That was just my spare.’

‘Wise up, Mule. Getting separated is apprentice stuff.’

Mule gave a noncommittal shrug.

The Doctor had enjoyed the performance, but there had been a lot of blood spilled on the doorstep. ‘Go up to the tower and finish your nap.’

‘Don’t get any blood on my sheets,’ Sofia sang as Mule went upstairs. ‘I’ve a reputation to protect!’

As her students giggled, she called to Secondo, ‘Keep an eye on this lot.’

‘I’m going with you.’

‘No one’s going anywhere!’ the Doctor barked. ‘You’re training.’

Secondo quickly wilted under his stare and retreated without protest. Sofia kept walking. The Doctor grabbed her good arm and pulled her out of earshot.

‘It wouldn’t have happened if I’d been with them, Doc.’

‘Keep your voice down. I didn’t train you to be a common street-fighter.’

‘What’s wrong with that? You’re one.’

‘Grow up. Someday soon you have to rule.’

‘If Quintus Morello had his way, I’d be dead already. You think the south will suddenly pay homage when I turn seventeen? Right now, the Bardini name is in the mud, and Scaligeri is neck-deep with it.’

‘You’ve inherited your grandfather’s rhetorical skills at least,’ he said patiently. ‘So what does my bloodthirsty Contessa propose?’

‘Nothing complicated. Cross the river. Crack some heads.’

The Doctor pushed her hard against the wall, slammed a fist down beside her face and glared.

‘What’s wrong with a good fight?’ she said coolly, all music gone from her voice.

‘The only good fight’s one you can win.’

‘What then? Do nothing?’

‘Not nothing. We wait.’

She pushed the Doctor away and went to the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...