- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

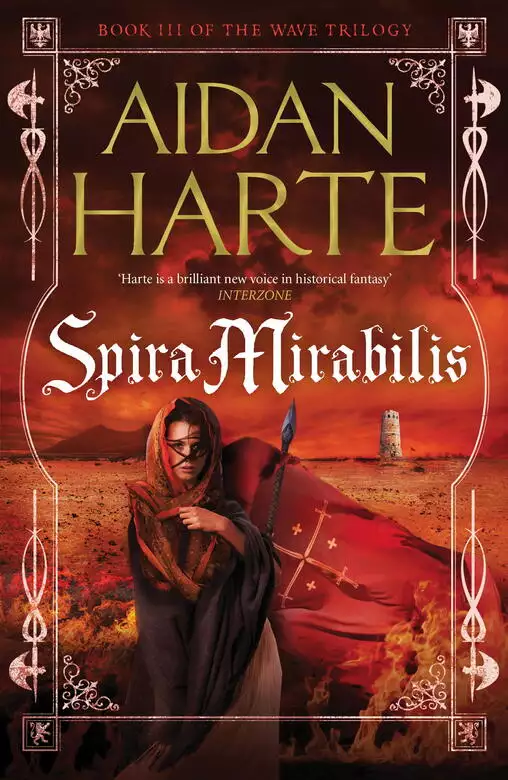

Darkness is falling and only Contessa Sofia can turn the tide in this thrilling final installment of the Wave trilogy. In the 1347th year of Our Lady the engineers of Concord defeated the fractious city-state of Rasenna using the magical science of Wave Technology. The City of Towers fought back, and for a while Concord's plans for domination were halted. But First Apprentice Torbidda regrouped, and reformed Concord to his own design. Now he is in absolute control, and plotting the final battle that will pacify Etruria . . . permanently. Contessa Sofia Scaligeri could rally her people once again, but she is far away in the Crusader Kingdom of Akka, trapped with her son by the tyrant Queen Catrina. Darkness is falling. The final battle must be fought and the tide must be turned, lest evil reign forever.

Release date: March 27, 2014

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 504

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Spira Mirabilis

Aidan Harte

RASENNEISI

OTHER ETRURIANS

OLTREMARINES

EBIONITES

Some doubted their eyes. The mutilated corpse, they argued, could have belonged to anyone. These doubters were swiftly silenced because believing that Fra Norcino – their shepherd, their teacher – had abandoned them was even more terrible than believing he was dead. The engineers had scourged Consul Corvis, the devil who ordered his execution; now, leaderless and denied even the solace of revenge, the fanciulli retreated to the Depths. Unity had been their great strength but they broke willingly into gloomy covens, to argue amongst themselves about what had broken them, and why. A deficiency of faith was the explanation that held sway for a few dismal days, before a sweeter notion suggested itself.

This was a test.

What was Consul Corvis? An engineer.

Who had shown them the body? The engineers.

And what was the First Apprentice but an engineer – the king of that benighted race.

*

Monte Nero might tower over the New City, but its foothills were in the Depths and those twice-orphaned wretches threw themselves, pushing and shouting, like a wave at the crags. When the folly of that became clear, they retreated to the Umbilicus Urbi, the cartographic navel of the Concordian Empire, whence the mapmaker’s needle began its tireless revolutions, to meditate on the injustices done to them. The ancient stone pillar was not merely the point from where all imperial measurements began, it was the pulpit from which Norcino had preached. Here the truth had originated, and against it was measured the falsehood of all other positions.

They alternated chanting, Abasso Torbidda! – down with Torbidda! – with Abasso Spinther!

The objects of their hatred were the two boys who controlled respectively Concord’s civic and military wings: First Apprentice Torbidda and General Leto Spinther. Though the mob did not know it, this singular pair were looking down upon them from one of the New City aqueducts. Both had devoted their lives to Reason, and both knew this sea of passion was capable of drowning them.

Beyond that, their reactions were very different.

‘Look at it, Leto,’ the First Apprentice marvelled. ‘The great beast that is man in aggregate. What an army they would make!’

The young general was unimpressed. ‘A man can be worth something, but men are generally worthless. I shall gather the praetorians. A charge will soon break up this rabble.’

‘No, they’d just come back. I must speak to them.’

‘You can’t reason with a mob.’

Torbidda smiled so rarely that his gleeful laugh took Leto entirely by surprise. ‘Who said anything about Reason?’

*

No one assaulted the boy in red as he pressed through the crowd – the praetorians saw to that – but once the masses would have parted like cattle before the First Apprentice. Concord’s year of anarchy had made them bold.

‘Down with the Guild!’ they shouted as he stood with bowed head before the pillar from where the blind preacher had hurled his sermons. Bloody handprints marked it still. He turned and looked contritely at the hostile faces surrounding him, and they saw a boy not much different than them: paler, perhaps, but with his ox-like brow and large callused hands he looked like one who knew what it was to work.

It was hard to hear at first, so choked with grief was his voice. ‘We mourn together, Children. Hear me not for my rank but for that woe we share,’ he started solemnly. ‘My rank is but an ephemeral vanity. Our grief is eternal. The saint’s pillar is empty, and so it must stay. No one can take the place of Fra Norcino – not you, not I’ – he stepped away from the protection of the praetorians and gestured contemptuously – ‘and certainly not them.’

The crown lowed aggressively, but no longer at Torbidda.

‘Nor can the Collegio dei Consoli replace him,’ he continued, ‘for all their claimed wisdom. A surfeit of Reason has enfeebled their minds. That scoundrel Bernoulli said that only philosophers could uncover truth, but I say that only you have that power! Your roar is the voice of God – give thanks that Bernoulli and his dogma are dead. Give thanks that Fra Norcino and his promise will live for ever! We, his children – we shall be tyrants to the world: we shall be a new breed, the tyranny of ten thousand! Cast off your petty bonds, your family, your names, and in this union forget your mothers, your brothers, your neighbours, your lovers. Forget all bonds and become something greater. Our unchained strength and collective stature is unbounded. O joy! O terror! How our senses will be magnified: a hundred eyes and ears, a thousand mouths to bite our foes! A million fists to smash the world!’

He walked amongst them so that that they could see he was just a boy like them. ‘We are young, that is why the Fra believed in us. He showed us the path and gave us courage to follow it. He threw away his life to free us from the snares of Reason. The Molè was a temple to that discredited idol, and we shall have nothing to do with it. Tear up the stones of the streets with your fingers; carry all you can on your backs. Load them till your knees buckle – and there on the grave of idolatry we shall build a new church dedicated to youth! Come, climb the mountain with me! Lay out the site with me! Cut the foundation stone with me!’

‘Lead us!’ they cried.

‘If you will follow me, then I will follow you. I tell you there is no greater rapture than to forget yourself. Become the Temple! Make stone of your flesh – make mortar of your bones and blood. Give your lives for Concord – for those who build and those who kill for Concord are equally brave, equally blessed: we are soldiers of God together.’

Leto, looking on, could hardly believe his ears. Instead of pacifying them, Torbidda was driving them mad.

‘I have no need of this gaudy robe, for I am no Apprentice.’ And as he spoke, Torbidda began to remove his clothes.

‘Then you are the master!’ cried an ecstatic girl, and the cry was taken up.

The surrounded praetorians, out of self-preservation, bowed low, and Leto bowed too, lower than everyone, to cover his indignation.

Torbidda, standing naked before them, picked up his Apprentice’s robe and threw it into the throng. ‘Tear it!’ he shouted. ‘Everyone take a share!’

‘Master!’ they insisted, ‘Master!’

‘We are all masters! Dip your wool in the blood of the lamb and be reborn. Children, we are Crusaders.’

Leto had to struggle to get to the head of the procession as Torbidda led a trail of naked children up the mountain. Like his followers, Torbidda’s feet were bleeding. In all the years Leto had known him, he’d never seen such an ecstatic smile. He threw his cloak over his naked shoulders and whispered, ‘Have you gone mad?’

Torbidda turned, and Leto fancied that he saw in his friend’s face – for the briefest moment – a look of terrible entreaty. Then it was gone, glazed over by joyless glee. He threw off the cloak impatiently. ‘On the contrary: I know now the true price of things. Concord is certainly worth a mass.’

Serves you bloody well right for doing the right thing! Captain Khoril raged at himself. The diminutive, hirsute Levantine was waiting to be summoned, and sweating like the last hog of winter. This was the first time he’d returned to Akka since helping Contessa Scaligeri escape Ariminum and the Moor. It didn’t help matters that the Moor’s ensign was standing calmly beside him. The tall, handsome youth with skin the colour of liquid walnut had a noble mien and a haughty diffidence; Khoril had ferried the perfectly composed youth from Ariminum to speak on his master’s behalf.

A black-robed cleric pushed open the door to the throne room and stared at them for an awkward moment, then, apparently satisfied, he ordered them to approach.

‘I summoned the Moor,’ said the queen. ‘He sends his cupbearer?’

The ensign’s eyes, deep sleepy pools, opened wide. This was mild reproach for Queen Catrina, but the beautiful youth responded defiantly, ‘Admiral Azizi sends his dearest friend. Loyalty keeps him in Ariminum. You would commend his prudence if you knew the Serenissima’s reputation for treachery.’

She said with resignation, ‘All the world knows that. He did as instructed and offered allegiance to Concord?’

‘Yes and as you predicted, they stood by and let us take over Ariminum.’

‘What then has your master so worried?’

‘I would not say worried. As canaries are to miners are rats to mariners. He smells one.’

‘I’m told it’s quite a distinctive musk. Is that so, Khoril?’ Before the captain could stammer an answer, the queen continued, ‘You mean this boy king – the one who styles himself the— What is it your Beatitude? The journeyman?’

‘I believe he calls himself the Apprentice,’ said the patriarch, striking the appropriate note of scepticism.

‘The First Apprentice,’ the ensign corrected him. ‘Mock all you like, but Admiral Azizi believes he will feed us to the beast as soon as he gets what he wants.’

‘Which is the Contessa?’

‘Just so, your Majesty, which is why my master recommends you don’t hand her over.’

‘And what am I to do with her instead?

The ensign, oblivious to the queen’s sarcasm, looked surprised. After a moment, he answered, ‘Kill her, of course.’

While Captain Khoril glared at his companion, torn between fear and hate, the queen glanced at the patriarch.

‘Tell the Moor,’ she said at last, ‘that I have already decided what to do with that one. Tell him too that next time his queen summons him, he had better come himself, not send some overbold Ganymede. Dismissed.’

Fury flickered across the ensign’s handsome face and he looked about to retort, but then he thought better. He gave a shallow bow and turned on his heels.

Khoril did likewise, happy to escape the royal reprimand he’d been dreading, but her silky voice stopped him dead.

‘I expect you are eager to see your family, Captain?’

Her voice paralysed him. ‘ … very much, your Majesty—’

‘Then I will not detain you for long.’

The ensign shot Khoril a look of suspicion and warning before the cleric showed him out.

Khoril’s mouth went dry and he resolved to head off whatever accusations she might make with his own. ‘I must remonstrate, your Majesty – why did you not tell me the Moor was your servant?’

‘You of all people know that a captain must not share everything with his crew. You are too hot-blooded to lie convincingly. Your enmity with the Moor is famous; the Ariminumese had to believe I wanted him dead too.’

‘I played my part so well that I helped the contessa escape.’

‘Yes, an embarrassing episode – But irrelevant now that I have custody of her.’

‘A captain needn’t share all but neither should he leave his servants wholly blind. The better I know your will, the better I can serve. What are you going to do with her?’ Khoril hoped he was doing a good job of keeping his sympathies concealed.

‘The Moor’s prescription is extreme. I buy time by keeping her alive. Contrary to appearances, my power is circumscribed. I cannot summarily dispose of her – sending her away or otherwise – and preserve Akka’s reputation as a safe haven, so I have engineered a situation, one where my subjects will clamour for me to cast her out.’

Khoril concentrated on looking stupid. He was appalled by her callousness, but he knew better than to show it.

‘But tell me, what is really on the Moor’s mind?’

‘His pretty friend spoke true: he’s worrying about the First Apprentice. The Moor is one of these sailors ever watching for the next storm. You’ve put him on a throne in a rich city across the sea upon which Concord’s shadow falls. He preyed on your ships as a pirate – what is to stop him doing worse now that he is Doge of Ariminum?’

‘Gratitude?’ the queen ventured, then laughed at her own joke. ‘Please, Khoril: I don’t need your counsel to navigate these seas. I’m well aware of the risks involved in employing such a duplicitous dog. But necessity obliges me to use the tools at hand.’ She rose from her throne and turned to the balcony, gesturing with a flick of her head for Khoril to follow. ‘I asked you here because of this.’

Akka had a natural harbour, and though the queen’s predecessors had spent little bettering it, the trading fleets of magnates like Baron Masoir made it a busy one. The quickest way from Akka to Byzant had always been by sea, and thanks to the Sands’ incursions, it was now the safest way too. As the faintly rotten smell touched her skin, she said musingly, ‘Who controls the Middle Sea controls the world: so said the Etruscans, and it’s as true today as it was then.’ She turned back to Khoril and said, ‘Within a year, Concord will have subdued all Etruria, from the Irenicon down to the Black Hand’s filthy fingernails. It’s inevitable. And when the final city falls, Concord’s unsleeping eye will look to me. I have a reprieve, a few months at best. Whether the Moor gives Ariminum to Concord or they take it by force, the sword that will strike us will be the Ariminumese fleet. Our navy is old: a few worm-ridden cogs, barely adequate for patrolling our coasts. I want you to build us one that compares to Ariminum’s.’

She stared at him, awaiting his reaction as he struggled to find a way to respond politely, ‘Majesty, the Golden Fleet—’

‘—is large, and the work of generations. I know that. “Compares to”, I said. We don’t have to equal them – our fleet need never leave its moorings to accomplish its job. It’ll stay the ambitions of these Etrurian dogs simply by existing.’

‘With all due respect, your Majesty, I think you underestimate the scale of the task.’

‘I own the forests of Lebanon.’

‘Besides dry timber, we’d need pitch, hemp, tow, cordage – and sailcloth by the acre besides. Not to mention skilled shipwrights—’

She handed him a parchment bearing the Guiscard seal.

‘Bring this to the Moor. You sail for Ariminum tomorrow. You will deliver this, along with your other cargo.’

Khoril looked at the document with undisguised alarm.

‘It’s an official request for those building materials we lack,’ she said, ‘and arsenalotti who know how to use them.’

‘The Moor won’t be happy.’

‘No, but he’ll provide them to keep me happy. That’s if he hasn’t decided to betray me yet – in which case, he’ll hang you. Get what you can. If it comes to it, I see plenty of merchant vessels I could confiscate.’ She flashed a smile. ‘Baron Masoir’s, for instance. Any other objections? Good. When you reach Ariminum you might decide to betray me yourself – be assured that no matter what happens, my dear captain, I’ll take care of your family as if they were my own flesh and blood.’

*

Sofia took aim at the empty eye, imagined it was Queen Catrina’s and fired. ‘Merda.’

Arik was teaching her to sling in a derelict piazza in the Ebionite Quarter. For targets, they’d gathered shards of broken masks from under the Madonna Murtha niches. ‘You’re throwing from your elbow. You must use all your strength’ – he swivelled at the waist – ‘like this.’

‘Easy for you. You wouldn’t dance so pretty with a baby due.’

The palace was the domain of Catrina’s retinue, so Sofia took every opportunity to escape. She was free to roam the bazaars, to attend mass and pageants – but she had been imprisoned before and she wasn’t fooled. Her unborn child was a prisoner within a prisoner, surely, the worst confinement. At least Akka was not a maze any more: she’d gradually become familiar with the back-streets and the people who lived there. She knew now that the Sown, Akka’s Ebionite population, were captives too – but one thing remained a mystery to her. ‘Why don’t you throw them out and take over?’

Arik picked up a stone and studied it. ‘We are not so many as we were, and besides, it’s not so easy.’ He discarded the stone. ‘To what are you loyal?’

Sofia thought a moment. ‘Tower Scaligeri. The workshop. Rasenna.’

‘Your home, your workplace and your city. Anything else? Eutoroor-eea?’

She smiled, because it sounded exotic in his accent. She made a grasping-at-nothing gesture, ‘That’s like—’

‘A mirage. We have no time for abstractions either. In the Sands, a man’s first loyalty is to his tent: his parents, his sons and their children.’ Piling one pebble on another, Arik showed her how the bonds of kinship came next: a typical lineage embraced fifty tents; lineages laid claim to certain wells and oases and fought together to defend those rights. Beyond that was the tribe. ‘And here things again become’ – he made the same grasping gesture – ‘abstract. A tribe is composed of lineages that have traditionally allied. They claim common ancestors and common enemies. The head of each tribe is the nasi.’

‘The king,’ Sofia said sourly.

‘Not quite. Nesi’im are more in the order of judges. So that is how it should be: tent, kin, tribe’ – he suddenly smashed his little tower with a wave of his hand – ‘but in these corrupt times one cannot trust a brother, so how could the tribes unite? And how, disunited, could we oppose Akka? One day things perhaps shall be otherwise, be’ezrat HaShem.’

‘Be’ezrat HaShem,’ Sofia repeated. ‘You say that a lot.’ She’d learned a smattering of Ebionite from Ezra on her voyage from Etruria and had plenty of practice since. She had an ear for music, and it made her a quick study of languages too, though to confuse matters, the Ebionites and Akkans communicated in a mongrel blend – and always in argument. But word by word, she was finding her way in.

‘Do I?’ He grinned bashfully. ‘It means “God willing”. God’s will is all that keeps Akka’s walls intact. Akkan unity is another mirage.’

This surprised her; she’d found ordinary Akkans almost as unfriendly as Catrina’s courtiers. ‘They all support her—’

‘They rally round the throne because they’re terrified. Never underestimate the value of an enemy with unknown numbers and seemingly limitless reach. Anyone the queen considers a threat gets his throat cut in the night, and the Sicarii get the blame.’

‘That’s one way to end an argument,’ she said, picking up a pebble and tossing it in her hand. ‘Do you imagine Fulk will ever realise how unworthy she is of his devotion?’

‘Be’ezrat HaShem.’

‘Do you see the Grand Master much these days? He’s avoiding me.’

‘That is discretion. If Fulk is seen with you, the queen will hear of it.’

‘I don’t care what she – uhh! – thinks.’ The pebble left her sling smoothly and shattered the chunk of mask into shards.

‘Good shot, Contessa – but you really should care.’

*

When the day got hotter, they went to the bazaar to find refreshment and Levi, who’d spent the morning circling the harbour, doing what he did best – talking. There was much trade between Akka and the Three Sicilies, so he swallowed his dislike of the slave-owning captains and struck up conversations where he could, pretending to be homesick. In reality, he was trying to find a ship they could stow away on to get back to Etruria.

The impending Haute Cour was an event rare enough to draw a crowd, and the bazaar was full of people, like Levi, enquiring into things that didn’t concern them. Traders brought many treasures into Akka, but none was more precious than gossip from the Sands. Town-dwelling Ebionites might disparage their desert kindred as lizard-eaters, but they still yearned to hear of the comings and goings, marriages and funerals, raids and ransoms of the world they had abandoned. And each tribe’s dearest wish was to see the Lazars set upon their rivals.

All the Sown were collaborators in a sense, but there was a special cloud of suspicion about Arik, in part owing to his antecedents, in part because of his friendship with the Grand Master. As she tried to keep up with the chatter, Sofia occasionally intercepted covert scowls directed at Arik, which he either missed or ignored, too busy was he sifting and comparing information to piece together a picture of the shifting sand that was the relative strengths of the tribes. His continuing interest, naturally, was the Sicarii.

The assassin band had been in decline before the recent skirmish at Megiddo. By blundering into an obvious Lazar trap, their nasi had dishonoured himself and them. For all their notoriety, the Sicarii lacked the one thing that kept tribes together in tough times: blood links. Many cells had evaporated by desertion. Arik listened to these reports so calmly that no one would ever guess that their leader was his brother.

Sofia spotted Levi in the midst of a heated conversation with an orange-seller. She’d seen him before, a big man with a body like a collapsed wall and a face defeated by hardship.

Levi waved excitedly to Sofia and Arik. ‘Listen to this,’ he said.

The orange-seller was not his usual miserable self, laughing as he punctuated his story with bright, animated gestures. Sofia’s Ebionite was not good enough to keep up, but when he’d finished, Arik thanked the man effusively and walked away with three fresh oranges.

‘Well?’ said Levi eagerly.

Arik distributed the fruit before starting, ‘I heard that story at my father’s knee, Levi. The Sands are full of fantasies that drift like the wind from tribe to tribe, growing ever larger in the telling. Dreams acquire substance and wishes harden to facts.’

Sofia was annoyed at being left. ‘What did he say?’

‘That the Day has come, that the people’s burden has grown too onerous, that the Old Man has returned to make all things right. Every summer some fool stays out in the sun too long.’

‘This is different,’ Levi insisted. ‘He’s not repeating a rumour, he saw the Old Man himself. He heard him preach.’

‘Levi, I know your mother told you those same stories but, believe me, the credulous are always disappointed.’

‘He heard him?’ said Sofia. ‘What did he say?’

‘That if tribes cease feuding, the Radinate can be restored.’

‘And when it is,’ she said warily, ‘this preacher will lead it?’

Arik looked at her sharply, then admitted, ‘That’s the only thing that gave me pause, Contessa. Many pretenders have called themselves the Old Man, hoping to acquire power. This preacher, whoever he is, he says he’s merely a herald. The nesi’im aren’t happy that he’s stirring everyone up, but he’s so popular that they dare not molest him. So they let him preach, then urge him to go spread his message to the next tribe.’

‘He has no affiliation?’

‘Apparently not – another token of authenticity. All the old tales say the Old Man came from the East.’

Sofia saw that Levi’s attention was elsewhere. She followed his glance to a dwarfish Levantine who was looking over his shoulder. ‘Is that—?’

‘The good captain? I do believe it is.’

Khoril was a dour fellow at the best of times, but the reunion was a happy one. ‘I can’t believe you’re both alive!’

‘Same here,’ said Levi. ‘I thought for certain the Moor would string you up after we got away with Ezra.’

‘If I was not the queen’s admiral he would have. He’s got his shadow making sure I don’t get up to more mischief – I only managed to give him the slip because the queen doesn’t trust him either. Where is Ezra, anyway? The old sea-dog owes me a drink …’ His voice trailed off as he saw their smiles suddenly disappear.

Briefly, Sofia told Khoril how their voyage had ended.

‘Lost at sea? Madonna, I wouldn’t have thought it possible. The things that lizard-eater could make the wind do. I’ll miss him.’

‘So will we.’ Sofia steeled herself for the worst. ‘Do you know what happened to Pedro Vanzetti after we left Ariminum?’

‘Your friend, the young engineer? I understand the Salernitan ambassador helped him to escape.’

The news made Sofia’s heart glow, and not just because Pedro was safe. ‘See, Levi? I knew Doctor Ferruccio would never side with the Concordians.’

‘Well, war makes strange bedfellows.’

‘Speaking of which, Captain, there’s only so much I can learn from harbour scuttlebutt. Is it true that Veii and Salerno have formally committed to the League?’

‘True enough. I’ll tell you all about it if you buy me a drink,’ said Khoril, lowering his voice and looked at the Contessa. ‘And I need to warn you—’

‘—to keep out of the midday sun.’ The intruding voice made all three of them jump. The ensign stood there, blandly smiling. ‘You run the risk of ruining your wonderful complexion, or worse. Sunstroke would be most dangerous in your condition.’

Sofia stared back at him. ‘Thanks for your concern.’

‘Why don’t you go on with Arik to the Haute Cour, Sofia,’ said Levi. ‘I’ll find a suitable tavern for these gentlemen.’

*

It took two strong men to open the doors of the Haute Cour; Fulk took one side, Basilius the other. Beneath the marble floor of the court was a well-equiped dungeon – but though the foundation of Akkan justice was decidedly dark, the courtyard itself was awash with light. At the end of the courtyard was a wooden chair, well carved and jointed, but simple, unostentatious: a poor seat for a queen, but the Haute Cour and its customs had come into being when Akka’s kings were weak.

Basilius might not care much for his Grand Master, but Fulk was glad to have him there; whatever else Basilius was, he was certainly efficient. Time was precious in the Order of St Lazarus, and talented brothers were swiftly promoted. As seneschal, he was responsible not just for maintaining the patrols’ supply-lines but for keeping Akka’s citadel and the network of towers in the Sands manned and in good repair. Basilius still appeared to be in good repair himself; the leprous teeth gnawing his extremities had not yet bitten too deep, for he could still deftly wield the ceremonial axe the younger Lazars could barely lift. But though his arms might be thick as old oak branches, the oak had a canker, and the hundred whispers telling a man his prime is past had become a constant harangue.

Stoic acceptance was a virtue that new recruits were taught, and for example they had only to look to their elders, for they endured terrible pain, especially at the end. Though many bore their trials with grace, some even being sanctified, an unhappy few found their faith decaying with their flesh, tormented by impious doubts worse than pain – for what sort of God repays a lifetime’s fidelity so poorly? Basilius was one of these inconsolables, and the young knights soon learned to avoid his wrath. Those paying attention had begun to notice a reek of rotten flesh lurking underneath the aniseed and camomile in which he daily soaked his surcoat and cloak, and his breath through the thin partition lips of his helm had become a sulphurous cloud. Even in private he never removed his helm, something which his fellow brothers mistook for devotion. In truth, the mask had long ago fused to the bloody scabs underneath.

The patriarch entered the Haute Cour first, swinging an incense tabernacle that filled the chamber with pungent smoke; he was followed closely by the drone of dolorous chanting. Behind him pressed the jostling crowd, all eager to get a good position, and Basilius began pushing back and cursing them like livestock.

Fulk stepped in before he hurt anyone, shouting, ‘Ease up at the back there! One by one, now – take your time. There’s plenty of room for all—’

Basilius shook his head wearily. He had never said outright that Fulk was Grand Master only because Akka’s queen was his mother, nor did he say in public that Fulk’s mildness nurtured enfeebling effeminacy in the ranks; he only remarked from time to time that the Sands have no use for softness. Fulk tolerated the innuendoes because the Order’s strength was as illusionary as Akka’s. Basilius was meticulous, dogged and unforgiving, and on days like today, he needed men who looked the part.

Clerics and clerks slunk about the edges of the court, assessing and pricing the various petitioners huddling in small groups, muttering behind soft hands. The members of the baronial party milling around Baron Masoir were conspicuous by the din they made; though they dressed as nobles in sumptuous clothes, their vulgar braying revealed them to be sang nouveau, little better than warlords. Only Masoir had anything remotely resembling an aristocratic bearing, though his big-fisted arms were the equal of any of the hauliers he employed.

‘Masoir thinks he owns the place,’ Basilius grumbled.

‘If he expects numbers to intimidate my mother, he doesn’t know her like he used to.’ Fulk gave the patriarch the nod, and as he and Basilius placed themselves either side of the empty chair, Patriarch Chrysoberges announced the queen.

A hush descended and the queen’s handmaids emerged from a side-entrance, followed by their mistress. She took her place and looked slowly around the court, her eyes coolly appraising the various groups, but not once did she glance up. The balcony was the only place where the Sown and Akka’s Small People could get a glimpse of what passed for justice in Akka.

Sofia and Arik were in the middle of that throng, watching.

The patriarch mumbled through a prayer for the queen’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...