- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

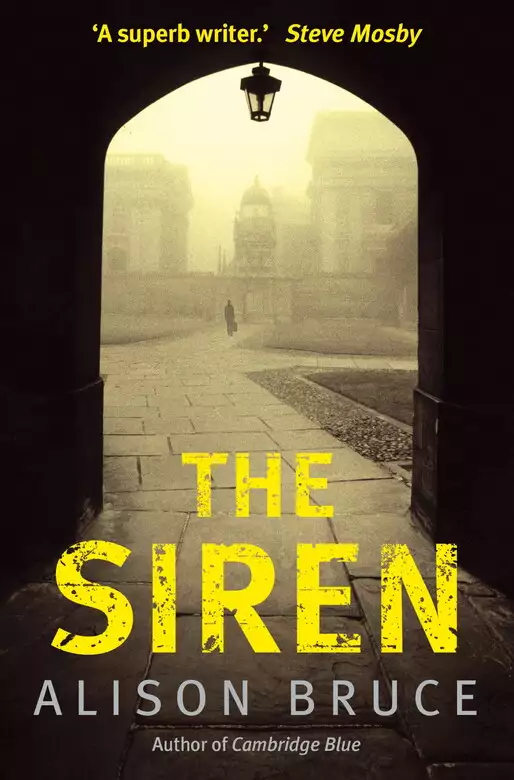

'Bruce is doing for Cambridge what Colin Dexter did for Oxford with Inspector Morse' Daily Mail All it took was one small item on the regional news for Kimberly Guyver and Rachel Golinski to know that their old life was catching up with them. They wondered how they'd been naïve enough to think it wouldn't. They hoped they still had a chance to leave it behind - just one more time - but within hours, Rachel's home is burning and Kimberly's young son, Riley, is missing. As DC Goodhew begins to sift through their lives, he starts to uncover an unsettling picture of deceit, murder and accelerating danger. Kimberly seems distraught but also defensive and uncooperative. Is it fear and mistrust of the police which are putting her son at risk, or darker motivations? With Riley's life in peril, Goodhew needs Kimberly to make choices, but she has to understand, the one thing she cannot afford is another mistake. Praise for Alison Bruce: 'Menacing and insidious, this is a great novel' R J Ellory 'A fast-paced gritty tale guaranteed to have you hooked from beginning to end' Cambridgeshire Pride 'A gripping tale of murder and mystery' Cambridge Style

Release date: July 22, 2010

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Siren

Alison Bruce

Also by Alison Bruce

Cambridge Blue

Alison Bruce

Constable · London

COPYRIGHT

Published by Constable

ISBN: 978-1-8490-1624-7

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Alison Bruce, 2010

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Constable

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Epilogue

To Jacen with love.

No More Blue Moon to Sing

– your lyrics say it all.

This book is dedicated to you.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is the moment when I can show appreciation to the people who have helped me. Top of the list are Broo Doherty and Krystyna Green who have been wonderfully supportive

throughout the writing of The Siren.

Thank you to Peter Lavery for his enthusiasm and thoroughness and to Richard Reynolds, Rob Nichols and Georgie Askew for their expertise.

For helping me research interesting injuries to live bodies I’d like to thank Dr TV Liew and for help with equally interesting dead bodies, thank you Dr William Holstein.

To Lisa Williams, Cher Simmons and Kat from Cherry Bomb Rock Photography – cheers, I had a great time.

And for both personal and creative reasons I’d like to publicly say a big thank you to the following:

Kimberly Jackson, Martin, Sam and Emily Jerram, Eve Seymour, Kelly Kelday, Claire and Chris, Stewart and Rosie Evans, Elaine McBride, Julia Hartley-Hawes, Dominique and Simon, Stella and David,

Martin and Lesley, Tim and Diane, Laura, Laura and Charlotte, Genevieve Pease, Michelle White, Jo and James, Brett and Renee, Nicky and Alex, Neil Constable, Rob and Elaine, Gillian Hall, Shaun

Gammage, Rob and Jo, Gloria and Martin, Barbara Martino and Alison Hilborne.

And last, but certainly not least, my totally brilliant step-daughter Natalie Bainbridge.

ONE

It was the red of the match heads that caught her eye.

Staring into the kitchen drawer, Kimberly Guyver had no doubt that the matchbook had been there since the day she moved in, and she didn’t see how she could have overlooked it.

Its cover was bent back, so she picked it up and folded it shut. Its once familiar design consisted of nothing more than two words printed in gold on black, in a font that she happened to know

was called Harquil.

It said: Rita Club.

She folded both hands around the matchbook, cupping it out of sight. She could feel the high-gloss card smooth against her palms. It reminded her how long it had been since her hands had been

that silky, her nails as polished. It reminded her of Calvin Klein perfume. Of impractical shoes. Of sweat and vodka shots. And the pounding bass that had drowned out any attempt to reflect on the

mess she was currently in.

Maybe the matchbook hadn’t been hiding, because maybe she hadn’t been ready to notice it until now.

She leant an elbow on the draining board, then plucked a match from one end of the row. It lit at the second attempt. She held it to the corner nearest the ‘R’ for

‘Rita’. The card curled before succumbing to a lazy green flame. She wondered if it was toxic, and realized the irony if it was. It burnt slowly until the flame reached the match heads,

which then ignited with a sharp bright burst.

She dropped the remnants of the matchbook into the sink, and kept watching it, determined to witness the moment when it finally burnt itself to nothing. It was down to merely ash and a thin

plume of smoke when the voice from the doorway startled her.

‘Mummy.’

She took a moment to wipe her face and hands – long enough for him to speak to her again. This time his voice was slightly more insistent. ‘Mummy.’ He looked at her with a gaze

that implied he knew far more than he was capable of knowing at two and a half, and she immediately felt guilty.

‘Riley,’ she answered, using the same urgent intonation. She held out her hand. ‘Come and watch Thomas while I take a shower.’

She paused by the window, noting the afternoon sun was now low over Cambridge’s Mill Road Cemetery, its glow picking out the wording on the south- and west-facing

headstones, casting the others in deep shadow. It was hot for June, and any areas where the ankle-high grass grew without shade had already taken on the appearance of a hay meadow.

The burial ground was shared between thirteen parishes. She knew this because she knew the cemetery better than anywhere else, better than any other part of town, better than any of the many

places she had briefly called home, even the one that had lasted for six years, or this current one where she’d lived for three. She knew the curve of each footpath, and she had favourite

headstones. Plenty marked with ‘wife of the above’, but none, she noticed, marked ‘husband of the below’. Lots, too, who ‘fell asleep’. And

if marriage carried kudos, so did age: in some cases a mark of achievement and in others a measure of loss.

She loved some stones for their ornate craftsmanship, others for their humble simplicity. She taught herself to draw by copying their geometry and scripts and fallen angels. The school claimed

she had a natural aptitude for art but she knew it was the cemetery that taught her balance and perspective, light and shade and the importance of solitude.

In isolated moments, when her feelings of abandonment became all but overwhelming, she’d return to certain memorials that had stayed in her awareness after her previous visits. Like that

of Alicia Anne Campion, one of the many who had fallen asleep. She’d gone in 1876 at the age of 51, and had been given a low sandstone grave topped with white marble, shaped like a

roof with a gable at each end and one off-centre. The elaborate carving was still unweathered. Kimberly knew how to find it at night-time and had often sat there in the dark, with her back against

this grave and the pattern close to her cheek, her fingers tracing the crisp lines that the stonemason had chiselled.

Mill Road Cemetery was also the place she’d hidden when, at fourteen, she’d tried her first cigarette, and where, at fifteen, she’d lost her virginity to a boy called Mitch.

She never found out whether Mitch was part of his first name or his last, or no part of his real name at all. He’d smoked a joint afterwards, and she tried it for the first and only time. He

then told her to fuck off. The smoke made her feel queasy and giddy, so she stumbled and caught her knuckle on the sharp edge of a broken stone urn, and went home with blood smears on her hands and

a new anger ignited in her heart.

But no bad choice was going to come between her and the way she felt for that place, and she later exorcized the memory of it with a succession of equally forgettable boys, until nothing but

Mitch’s name and a vague recollection of smoking pot stayed in her head.

People walked through all the time, taking shortcuts, taking lunch. People actually tending graves were few, and she guessed that the number of people who knew the place as well as she did was

even less. Most visitors didn’t know about the thirteen parishes; even fewer knew that the curved paths and apparently shambolic layout of trees and graves formed a perfect guitar shape.

She’d sketched a plan of it one day, then in disbelief double-checked a map and, sure enough, found this huge guitar hidden in the centre of the city.

The guitar’s neck belonged to the parish of St Andrew the Less and, although level with the rest of the cemetery, it stood a storey higher than the houses backing on to its west side. They

were Victorian terraces, originally two-up, two-down workers’ houses, but almost all of them had since been extended.

One of these was Kimberly’s. It had a single-storey extension that stretched to within a few feet of the cemetery’s perimeter wall. When she first moved in, she’d seen that as

providing a good fire escape: an easy climb through her sash window, then across the flat roof to safety. But, almost as soon as he had been big enough to stand, she’d realized Riley’s

fascination with the large open space that lay just over their garden wall.

For now, though, Thomas the Tank Engine was enough to hold his interest, so she left him sitting on one of her pillows, hypnotized by the TV at the foot of her bed. Just this one time, she hoped

he would leave her to shower in peace, enjoying the water close to scalding and the jets needling her skin.

She reached for a towel, realizing that she’d stayed in the shower for much longer than she had planned to. She could hear the Fat Controller having a few issues with one of the less

useful engines, and knew the DVD had been on for over half an hour.

‘Riley?’ she called. With no response, she guessed he was probably just too engrossed to hear her, and she called him again.

She took another towel and wrapped her wet hair in it, then returned to the bedroom just as the theme song began. Thomas the Tank Engine was chuffing along the track with the credits flying up

the screen, but Riley had climbed under the covers and was sleeping too deeply to care. Kimberly curled up beside him, wrapping her arms around him, and he shifted a little, resettling with his

head closer to hers. His hair tickled her cheek. He smelt of baby wipes and jacket potato, and his proximity soothed her more than any amount of showering could have done.

It was a tranquil moment, broken only by the main-menu loop on the DVD, then a few seconds of cheery music that had already been repeated too many times. Kimberly stretched herself towards the

remote, aiming to scoop it near enough to reach the mute button. She touched one of the channel buttons instead, and the image that flickered on to the screen seemed as familiar as Thomas the Tank

Engine.

She recognized that skyline, the rocky outcrop, the barren coastline. But she took a second or two to understand this was no DVD, no fictional footage. It was the news.

A fragment of her life was appearing on the television and, as sure as the carving on Alicia Campion’s grave, its details were now set in stone.

She felt realization burn through her chest, dropping like a molten leaden weight into the pit of her stomach. She saw the winch, and the wreck of Nick’s car that now hung from its hook.

The car that she’d last seen when that same stretch of the Mediterranean sea had swallowed it.

The reporter’s voice began to penetrate her shock. ‘The vehicle was recovered last week after some divers reported that it appeared to contain human remains. It wasn’t until

today that the Spanish authorities have been able to confirm the identity of the occupant. The victim is named as former Cambridge man Nicholas Lewton, who had been living and working in Cartagena

until his disappearance almost three years ago. Police are now appealing for information, and a spokesman has confirmed that this death is being treated as suspicious.’

The phone sat on the bedside table nearest to the window. It rang just as she was reaching for it. She looked out across the cemetery, towards the rear of another row of houses. Because they

were built on higher ground, her bedroom directly faced the rear windows of their ground floors. One of them had been sandblasted, leaving its brickwork paler than that of its neighbours. Trees

rose in-between, but she could see its upper floor catch the last of the sunshine and glow a fireball orange.

The ground floor of the same house was partly obscured in summer, but Kimberly knew that her caller was standing just inside its patio door. Probably squinting into the sun, staring over at

Kimberly’s house, waiting for her to answer the phone.

Kimberly pressed the ‘answer’ button. ‘I saw it,’ she said. ‘Let me get dressed. I’ll meet you outside.’

TWO

Kimberly grabbed some clean knickers and a bra from her chest of drawers, then pulled a dress from her wardrobe. Tugging them on quickly, she scooped up Riley, draping him over

her shoulder, hoping he wouldn’t stir, then managed to transfer him into his pushchair without waking him. She left her house by the front door, and hurried to the nearest entrance leading

into the cemetery, a narrow gateway at the top of the guitar’s neck. The path ran in an arc that curved like a broken string towards the other side of the green enclosure. She and Rachel

always met at the midpoint, a circle that had once been the site of the chapel of St Mary the Less.

Kimberly arrived first. There were four benches, spaced around the outside of the circle, and she chose the one which would give her the best view of Rachel’s approach.

It was a few minutes later before she saw Rachel’s figure appear briefly, then disappear, between the trees and shrubs further along.

She could easily have cut across and made it in half the time, since Rachel knew her way round here almost as well as Kimberly did. This was a good sign, Kimberly decided: a sign that Rachel

didn’t feel the same panic as she herself felt.

She watched Rachel reappear from behind a yew tree and disappear behind an overgrown buddleia, noticing that her friend’s stride, though brisk, was not rushed. Measured, that was

the word. Rachel was always the calm one, weighing up the options, measuring her response. It was a joke between them: Kimberly gets them both into trouble, Rachel gets them out.

The sun was at the back of her neck, reaching its still warm fingers around on to one cheek. It was a slow, burning heat that made her feel impatient to get out of it.

When Rachel emerged into view again, she was still about a hundred feet away, but Kimberly sensed there had been a change in her friend. In the few seconds she’d been out of sight,

she’d been overtaken by a shadow. There was now a slowing of her usually lively stride, a new gravity dragging at her limbs, like hesitancy and indecision were both pulling at her hem. There

was maybe eighty feet between them now, and Rachel’s features appeared as nothing more than shadows and indistinct shapes, but they were composed differently today.

Riley moved one arm out into the sun, and Kimberly used this movement as a reason to turn her attention to him and fold it back inside the shade of the canopy. She knew she was kidding herself;

in truth she felt like she’d been staring at Rachel, in some kind of bad way. She waited until Rachel was about twenty feet away before looking up at her again, hoping to find comfort

there.

Rachel’s toe caught in a small ruck in the grass and, momentarily, she stumbled. It was nothing, just a tiny break in her stride, but it seemed to be a further sign of the way her

previously graceful gait had become self-conscious and unsure. She stopped ten feet off, and managed a small smile: one that flickered on to her face and was gone in the next instant. Kimberly had

painted Rachel’s portrait many times, but never like this. Not ever. Something fragile but significant had deserted her friend.

Kimberly felt her stomach lurch.

She glanced around her, taking in everything as if it was the first time they’d come back to this spot in ten years. If the grass that lay between them looked the same as it ever had, it

was the only thing that did. The graves were older, some had crumbled, others had toppled. The surrounding houses were filled with new families. The drugs were harder, and year on year the rain

fell ever heavier. And neither of them were children anymore.

Kimberly stood up and stepped a little closer.

Rachel frowned. ‘I was as quick as possible,’ she said. And spoke as if answering a question. Making a defence.

‘I know. It’s OK.’

‘Is it?’

‘Shit, Rach, it’s got to be.’ Kimberly heard the tautness in her own voice.

In response, Rachel closed her eyes and pressed her hands over her ears. Kimberly had never noticed the frown lines on Rachel’s forehead until now.

‘Rach, what is it?’

‘We should go.’

Kimberly glanced around.

‘No, Kim, I mean go go,’ Rachel corrected her, ‘leave the area until it’s sorted.’

‘We already did that, remember?’ Kimberly’s thoughts were suddenly overtaken by the idea that she’d seen some fundamental part of the picture through the wrong lens, or

from the wrong angle. She couldn’t decide what exactly, just that her view had somehow become distorted.

Rachel shook her head and turned away, but not before Kimberly had spotted the tears welling in her friend’s eyes.

She found herself at Rachel’s side, wrapping her arm around her shoulder. ‘This isn’t like you at all. I’m relying on you to bail me out.’ Kimberly gently turned

Rachel’s face towards her. ‘Tell me what’s wrong.’

Kimberly guessed she knew Rachel better than anyone, and she could only remember Rachel crying twice before, once at her mother’s funeral and once at school on the day they’d met.

Kimberly was the emotional, volatile one, while Rachel was the thinker, the planner. Never the crying type.

Rachel blinked and tears fell from both eyes, making identical trails down each side of her symmetrical face. She didn’t meet Kimberly’s gaze, but instead stared past her and into

the pushchair. She tried to speak but the sentence churned into a sob. There was definitely something odd about the way Rachel stared at Riley, and the unease twisted tighter in Kimberly’s

gut.

Rachel’s breathing steadied for a moment. ‘I didn’t know you’d have Riley,’ she blurted.

‘I wasn’t going to leave him indoors, was I?’

‘I don’t mean now. I meant . . .’ Rachel held out her hands in an expansive gesture, a gesture that said Think bigger.

‘You meant what?’ Kimberly demanded, but she could already see she’d been naïve. She felt a familiar anger rising, and she tried to restrain it, grabbing at its tail and

willing it to go quietly back into its cage.

Kimberly asked her again, knowing that her voice sounded hard and unforgiving. ‘What was it you meant?’

This was the wrong tactic with Rachel, and Kimberly knew it. Rachel stiffened, then pulled away and began walking the more direct route back to her house.

By the time Kimberly had manoeuvred the pram across the bumps and heavy clumps of grass, Rachel had almost reached the low wall before her back garden.

Kimberly spoke again as soon as she thought she was close enough to be heard. ‘Please, Rachel, I don’t understand.’ Parking the pushchair, she caught up with her finally and

reached out for the woman’s arm. ‘What’s scaring you, Rach?’

The next moment Rachel was hugging her, constantly repeating her name. Kimberly held her close at first, gripping her as tight as she was being gripped. Then the seconds began to stretch on too

long. This wasn’t just an expression of close friendship, and Kimberly didn’t understand it. It began to feel claustrophobic. She needed to know what Rachel was now feeling, needed to

catch her breath and assess this new pitch of emotion. Is this love or fear, or something else? Regret perhaps?

But, in their relationship, Kimberly believed she was the sole custodian of all the regret. She’d held on to it for so long now.

She eased herself free.

‘I know how much I owe you. I’ll never forget that, and I’d never want you in any danger because of me.’

Rachel turned to her, her eyes already puffy and her nose running. Her words sounded thick and heavy. ‘Everything’s scaring me. You, Stefan . . . the whole fucking, miserable

mess.’

Then, Rachel began backing up as she continued, ‘Go away. Take Riley and go. I’m not going to tell you anything you don’t already know, so don’t ask me any more. Just get

away from Cambridge.’

‘I don’t know everything, do I? What’s it got to do with Riley?’

‘Kim, there’s nothing else I can say.’

‘There is. Just tell me what’s happened.’

Rachel hesitated and, when she finally spoke, her voice was barely audible: ‘You saw the news?’

Kimberly couldn’t let it go so easily and followed her right up to the low wall. ‘Spain’s a thousand miles away, probably more. It has nothing to do with Cambridge.’

Rachel shook her head and stepped right over the wall. They were only thirty feet from the pushchair but Kimberly wasn’t prepared to be any further from her son. She hurried back to

collect it, and pushed the buggy towards Rachel. ‘Wait, there’s something else, isn’t there?’

‘You really must go away from here.’

‘I can’t just vanish.’

‘You have to. I’m going early tomorrow.’

‘Without Stefan?’

‘No.’ It was Rachel’s instant answer, then she checked herself. ‘Maybe. Look, the less you know the better.’

‘You’ve had it all planned.’

Rachel shrugged, but seemed increasingly uncomfortable.

‘Why didn’t you warn me earlier?’

Rachel shook her head. ‘It was an old plan – one we never thought we’d need.’ Again her gaze alighted on Riley.

‘Is he in danger, too?’ Kimberly whispered.

She guessed Rachel wished she could deny it, but instead she gave her a small nod. It did nothing to soften the sense of betrayal: Rachel had let her down but more than that she’d let

Riley down.

The truth of the situation seemed to strike Rachel only then. She paused, then said, ‘OK, how long do you need?’

Kimberly couldn’t help the sarcasm. ‘To arrange a new life?’ she snorted.

Rachel didn’t visibly react. ‘To collect some cash and a car and go,’ she said quietly.

That sobered Kimberly. ‘I don’t know.’

‘I’m all ready. Why don’t I take Riley for a few hours? Pick him up when you’re sorted.’

‘I don’t know . . .’

‘It’s all I can offer.’

And Kimberly could tell then that there was no half-truth or selfishness in the suggestion. ‘Help me get the pram over the wall.’

Rachel nodded reassuringly. ‘You know I’ll look after him. I’ve always tried, you realize. And, Kim, please don’t tell anyone else what I’m doing.’

Kimberly nodded silently, then hung back until both of them were out of sight. She finally made her decision and turned – but not towards home. Instead she left the cemetery at the

south-west exit, then broke into a run.

Change was in the air, and it smelt sour. Maybe there was something bad coming, or perhaps it was already blowing in and opening up gangrenous wounds in her current life. One thing was certain;

it was stirring up the one memory that she never wanted to revisit: hot pavements and the sound of her own footsteps echoing on them as she ran for help.

THREE

Rachel was in the habit of deliberately studying her own house each time she approached it, no matter how short a time she’d been away or which elevation she was facing.

It was a habit she had developed as a form of motivation, a reminder of how far their hard work had brought them and what they could accomplish when they remembered to work together. She had

finally realized that such achievements had been brought about by nothing but her own determination. And, although her motivations subsequently changed, her habit of staring at the house

remained.

It was a mid-terrace residence with a small passage that led from the back garden straight through to the street at the front. Including this in its overall ground plan made the house several

feet wider than the neighbouring properties. It had allowed Rachel and Stefan space for an upstairs bathroom and an en-suite extension to their bedroom. The house was one hundred and seven years

old and had spent the entire post-war period mostly in the hands of the same family.

The first thing they had done was hire a skip. Apart from three brief trips to the landfill site near Milton, it remained outside for a full week as layers of the house’s history were

stripped away and discarded. The thick brown and cream lounge carpet, the wood cladding from the chimney breast along with the two-bar electric fire with the fake coals. A free-standing kitchen

unit and a Belling cooker. The twin tub with its flaking paint, rusting from the bottom up. A double bed with velour headboard and the plastic laundry basket printed with orange and yellow flowers

all over its lid. Interior doors, strips of old skirting, the sink, the bath, the immersion heater, and on and on until all that remained had been a windowless, featureless shell.

They’d then extended outwards at the back and upwards into the loft. And the builders had used the narrow side passage each time new building materials were delivered. Everything from

wiring and plaster to shelves and cushions was replaced.

But the passage itself stayed, too convenient to be deprived of it for the sake of a few extra square feet of floor space. They’d never worked out how to give the place a more contemporary

feel, and so this passageway and the one surviving plum tree stayed as relics of the house’s original guise as a cramped and unfashionable Edwardian family home.

Although Rachel always studied her own home in this way, she rarely thought about it in any depth. For some reason today was different, and by the time she’d manoeuvred Riley’s

pushchair in through the patio doors, she was preoccupied with the idea that she was leaving the one place they’d truly made their own.

She corrected herself: the one place she’d truly made her own.

Rachel drew a deep breath and wondered if living alone somewhere new would really be any better.

It was her exchange with Kimberly that had brought about this occasional sentimentality, Kimberly whose pregnancy had brought her a sense of purpose as well as a beautiful baby boy. Rachel loved

this house but it was just a house, a means to an end. Her next steps were all about getting herself to a point where she could afford to be sentimental. The chance to become as lucky as

Kimberly.

She lifted Riley on to the settee, . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...