- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

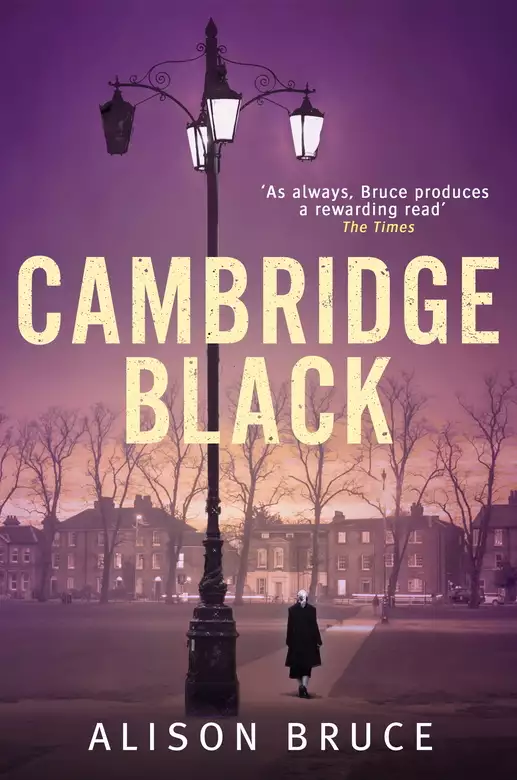

Synopsis

A cold case waits to be solved . . . and a killer waits in the wings . Amy was seven years old when her father was arrested for murder. His subsequent trial and conviction scarred her childhood and cast a shadow over her life until, twenty-two years later, new evidence suggests he was innocent and Amy sets out to clear his name. But Amy is not the only person troubled by the past. DC Gary Goodhew is haunted by the day his grandfather was murdered and is still searching for answers, determined to uncover the truth about his grandfather's death and find his killer. But, right now, someone is about to die. Someone who has secrets and who once kept quiet but is now living on borrowed time. Someone who will be murdered because disturbing the past has woken a killer.

Release date: February 23, 2017

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 295

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cambridge Black

Alison Bruce

‘Thank you, Nadine,’ the guitarist shouted and the crowd cheered for more but she handed the microphone back to the band. She knelt down to unclip her guitar case, taking her time to remove the strap from her Gibson before placing it in the velour-lined case. Her slowness was deliberate; she loved the singing but hated the fuss. Hated the drunks nearest the stage – not them perhaps but their cigarette-permeated breath and their insistence. And lack of inhibition when it came to pulling at her, or grabbing her into a hug and giving advice and compliments with alcohol-spittled words. She turned her back on them to pack away. It was usually enough for them to disperse.

The Boat Race pub had its music-loving regulars but tonight, hours after the actual boat race, it seemed it had become the place to go to commiserate over the latest Oxford win, and new faces outnumbered the familiar. She glanced up a couple of times and, on the second, caught sight of Theo near the jukebox. He leant back against the wall, typically unhurried. ‘OK?’ he mouthed.

She rolled up her strap and tucked it away in the space left by the guitar’s cutaway body, slipping her capo and picks into the space alongside it. She could sense Theo watching and, inside her head at least, she smiled. Securing the case was another not-to-be-rushed ritual and, by the time she’d clipped the last latch and turned back to face the room, the majority of the punters had moved on.

Carrying a guitar before a gig would always elicit ‘go on love, give us a song’ type comments. Afterwards, it seemed to get a little respect; she didn’t need to push through the stragglers to reach Theo; people, even the drunk ones, stepped aside or shook her hand and said she’d done well.

Theo took the case from her and she followed him out onto East Road where it was almost as noisy but less congested. ‘How was it?’ he asked.

‘You were there, weren’t you?’

‘Hiding at the back. I mean how was it for you? It’s hard to tell when you’re so wrapped up in what you’re playing.’

They were walking side by side now and she grabbed his arm and squeezed her face against it. Apart from that, she didn’t reply. She couldn’t imagine how she looked when she sang; she felt as though it was all written across her face, a transparency – it was never acting and her emotions were so on show that it had to be obvious to anyone watching that they were real. Singing to herself and practising new songs never had the same effect. It was only from the moment that the audience started watching that she had no choice but to commit to the performance. She could sing and play and be barely in the room then, free to touch the thoughts that were too hard the rest of the time. She doubted whether she wanted to know what expressions might flash onto her face. She preferred the idea that there were none.

She didn’t ask where they were heading. The evening had become cool but she was content with the idea that they’d take a slow walk and eventually find their way back to Theo’s flat.

She wondered whether it always took an unhealthy relationship to make a good one seem valid. Maybe only screwed-up people felt the need to put themselves through that. She slipped her hand into his. ‘I can stay over, you know.’

He grinned, ‘I was hoping you would but I’ve still only got a mattress on the floor. It’s still pretty squalid.’

‘It’s not squalid. Just basic. And it’s the rest of it that needs to catch up.’

‘You’re not wrong there. I’ll move my furniture in the next couple of weeks.’

‘Don’t rush because of me.’

Eventually the house would be divided into six letting rooms but, at the moment, his was the only finished floor. ‘When Dad offered it for free I imagined it might be unsophisticated . . .’

‘You have electric and running water.’

‘And I’m just like the live-in guard on a building site.’

‘It’s not so romantic when you put it like that.’

‘Still coming?’

‘Of course.’ He wrapped his arm around her shoulder and she curled hers around his waist. Neither of them seemed to set the pace but they meandered, each in step with the other until they reached the rise of the Mill Road railway bridge. They stopped and watched a packed train rattle towards the station.

Passengers crowded the aisles, waiting to disembark, to swap a day in London for a night in Cambridge. She rubbed her thumbs against the guitar-string hardened skin at the tips of her fingers. How many train songs were there? Was there a better metaphor for life than a train song?

‘What are you thinking about, Nadine?’

‘About train songs and wondering which one fits me.’

‘I wasn’t expecting you to say that.’

She looked up at Theo. ‘I’m pretty sure mine’s about coming home.’

‘I hope so.’

Instead of moving away again, he leant against the metal panel, his back to the tracks now. It was an exposed spot and she shivered. ‘Can we go?’

‘Of course,’ he said, but still didn’t move. He seemed to be waiting for something, but she didn’t know what.

‘Is something wrong?’

‘Nothing.’ He shook his head slowly; ‘I was trying to find the words to tell you how much it means to be here with you.’

‘Watching trains?’ She always found it easier to deflect serious comments but this time she wished she hadn’t. ‘Actually, there’s nowhere I’d rather be.’

He kissed her gently, then his cheek brushed hers as he spoke softly in her ear, ‘I love you, Nadine.’

She closed her eyes and let her senses fill with the smell of his skin and the warmth of him. She had been scared that her feelings had jumped too far ahead but now she knew that they both felt the same way.

And, as though he’d read her thoughts, he pulled her closer. ‘You don’t ever need to worry, Nadine, I’ve felt like this for a long time.’

‘Really?’

‘Absolutely,’ he grinned and Nadine smiled too. He kissed her again, their lips lingering and the last of the tension melting away. The air no longer felt cold and her earlier unease vanished. Maybe this would be OK. It felt right in the kind of way that she’d never experienced before. And that’s what people always said, you just know. They took their time walking back to the house in Romsey Terrace. She’d spent the last night there too but now she was more aware of the short street with one terraced house wider than the rest: the only one with a window on either side of the front door, the only one with loft windows and brand new frames.

‘It will be lovely when it’s finished.’

Theo’s gaze followed hers towards the roof, ‘I’ll have to share it then, won’t I? I like this endless building work; it means there’s just the two of us.’ He slipped the key into the lock and Nadine spoke quietly before he opened the door; all this would be forgotten once they were inside. ‘I felt uneasy earlier, kind of restless. Nervous for no reason. Like I shouldn’t come.’

‘And now?’

‘It’s gone and I’m glad I’m here. Glad I’m with you. I just wanted to say it before we went in.’

‘Speak your fears and chase them away?’

‘Something like that.’

He opened the door, set her guitar down in the hallway and reached back to her, ‘Don’t worry, we’re good. Everything’s good.’

The stair carpet hadn’t been laid yet and their footsteps clattered on the stairs with enough noise for more than two people. The second set of stairs sounded like a distant echo of the first. A few noises made it down after that, the running of a tap, a squeal of laughter, the bang of a door, then silence.

Another hour passed. The other houses stood with curtains drawn and lights extinguished. The bare windows let the sodium orange street light slip into the ground-floor rooms, the open doors letting it trickle into the hallway, picking out the outline of paper and paint and a guitar case standing on the bare boards.

At 3 a.m. the light died and the letterbox creaked open. The fluid trickled, softly splashing onto the coir mat, too quiet for upstairs to hear. A ball of paper was wedged in the letterbox, resting there just long enough to be lit then poked through. It hit the mat glowing then disappeared in the bloom of flame that rose from it. The hall and stairs flushed orange, then black as the smoke thickened. It crept up the stairs as the guitar case slowly melted.

Amy wouldn’t recall much about that morning. She remembered ordering a cappuccino and weaving between tables to her favourite at the furthest corner. Her dad was running late so she studied the faces of the jesters, hobos and harlequins on the walls and shelves, trying to pick out any new additions. Many had been here since her childhood when clowns had scared her and she’d stared at the straw bobbing in her milkshake to avoid meeting their gaze.

She saw them differently now, of course, and today it was the clown blanc that caught her eye. He stared sorrowfully, a black painted tear resting on the top of his cheek, his head tilted as though he was ready to listen. Had she felt melancholy he might have seemed sympathetic; instead, she looked towards the door and sipped her coffee as she waited.

It was less than a minute later when the door was opened by a woman wrestling with a pushchair. The sounds of outside burst through for several seconds, with the hum of the city cut through by the siren of an ambulance. Amy moved towards the entrance, curious but not yet concerned. She must have spoken because she could remember the woman looking at her then gesticulating in the direction of the city centre. Then the wave of apprehension. And Amy dashing onto the pavement with silence rushing in her ears and the only thing in focus was the patchwork of paving stones as she ran across them.

He lay on the pavement beside the kerb.

There was no crowd, just a couple of bystanders and two paramedics. And her dad. He was already on a stretcher, his shirt pulled open with wires and an IV line hanging from him. He lay still, his face bloodied, pavement dust and grit smeared across grey skin and she shouted even though she was close enough to touch the ambulance men.

‘Did someone hit him?’ When no one replied she added, ‘That’s my dad,’ and repeated it before anyone had the chance to respond. A stocky paramedic knelt close to her father, another, a lanky guy who looked about thirty, had opened the ambulance doors and was now bringing out the gurney.

‘What’s his name?’ he asked.

‘Robert Buckingham. I was meeting him for lunch.’

Perhaps they already knew his name because there was no demand for any proof of identity. ‘Does he have any existing health issues you’re aware of?’

‘No, I don’t think so.’

The other paramedic looked up, ‘Can you travel with us to Addenbrooke’s?’

‘Of course.’ She hadn’t taken her eyes off her dad. ‘What’s wrong with him?’

‘We’re running checks at the moment. I’m Grant. What’s your name?’ The paramedic spoke to her father next, ‘Mr Buckingham, your daughter Amy’s here. Mr Buckingham?’

She saw his mouth move, an attempt to form a word.

‘Dad?’

Recognition flickered on his face. Her world slowed and steadied again, she clasped his hand until they loaded him onto the ambulance then strapped herself into the spare seat. Would they let her travel with him if he was about to die? The younger of the two paramedics was driving now while his partner continued to work on her dad. They kept the sliding window open between them and passed comments back and forth. She felt the ambulance take a turn and, glancing forward, could see the traffic on East Road parting to let them pass.

‘Amy?’ Grant the paramedic prompted. He had a large notepad on his lap now, pre-printed with questions, boxes and the outline of a human body. ‘Are you his next of kin?’

‘I suppose so, I mean, there’s his mum and my mum but my grandmother’s in a care home with dementia and my mum . . .’ She stopped mid-sentence.

‘Are they married?’

‘Not any more. They don’t maintain contact.’ She studied her dad for a second, then added, ‘Unless they have to.’

Grant shot her a wry look. ‘Parents, eh?’ He reached across to check her dad again. ‘Mr Buckingham?’

Amy leant forward. ‘What’s happening?’

‘He’s gaining consciousness. Has he had any alcohol?’

‘I doubt it.’

He would have had a glass at lunch if he’d made it that far but he wasn’t an excessive drinker. At least as far as she knew. ‘Did someone hit him?’

‘The person who called us said he’d fallen and banged his head. People often say just that, though, it doesn’t always mean much.’

‘So it’s just a head injury?’

Grant pointed to a small square monitor. ‘We collect information on the way in, to give the maximum information. Your dad’s suffered a head injury but there’s ECG activity . . .’

‘His heart?’

And all she remembered of the rest of the journey was watching her father’s expression, silently trying to communicate, to let him know he wasn’t allowed to die young like his own father had. Beneath his tan, his skin had paled to the colour of alabaster and she remembered the clown with the tear on his cheek.

The weight of the day descended in early evening. Amy had spent the afternoon in a bubble; her dad had been wheeled into A & E and throughout the afternoon he had been seen by a succession of staff. Each had done something and asked something else before taking notes and moving on. And she had watched them move between beds, do the same with other patients then, in so-quiet tones, share their details with their colleagues. There was no panic here, no sense of shock or desperation. No windows either and the clock on the opposite wall ticked on calmly. They wheeled him away and left her to wait.

Finally, a doctor appeared, a Chinese lady with rectangular framed glasses and a clipboard pressed to her chest.

‘You are Mr Buckingham’s daughter?’

Amy nodded.

‘It seems your father suffered a cardiac incident and a head trauma as he fell.’ She stopped speaking long enough to see that Amy had listened and understood. ‘He is expected to make a full recovery. He has regained consciousness and you will be able to see him, but briefly. He will be drowsy.’

Amy didn’t absorb the rest of the details – she guessed there had been an operation – but she shook her head when the doctor asked if she had any questions. She sat beside her dad’s bed and his expression changed just enough for her to know his mind was clearing. The gash on his temple had been patched, the wound itself looked tame but the skin around it was swollen and turning purple. ‘You scared me,’ she told him quietly.

His right eyebrow twitched but he made no attempt to speak. She took out her mobile. ‘I’ll phone the agency. I won’t go in tomorrow.’

‘You don’t need to miss work because of me.’ His words were monotone and slow, but clear. ‘You need that job.’

She shook her head, ‘It’s just holiday cover, Dad, and it finishes tomorrow. I’ll explain and it will be fine.’

‘I worry about you.’

‘Well, you shouldn’t, temporary work suits me.’ She sat back in the chair and the PVC upholstery squeaked, ‘The doctor said I shouldn’t stay too long but I’ll come back up in the morning. Obviously.’

‘Thanks.’ He managed an indistinct nod.

She wanted to ask how he was feeling but it seemed as though it was a question for the start of a visit, an opening question. Instead she asked, ‘Can I get you anything?’

He turned his hand over and gently squeezed hers. ‘Would you ask your mum to come and see me?’

‘Really?’

‘I ought to give her the pleasure of seeing me like this.’ His brief smile vanished. ‘Seriously, Amy, some thoughts are very clear when you are lying in a pool of blood. You should get a regular job. I shouldn’t smoke. And, as much as we’ve never been amicable, your mother and I have unfinished business.’

She caught a bus back to the city centre, the artificial colours and sounds of Addenbrooke’s were gone and she was returned to the other end of the same day. It had grown dark outside and the face of the clown blanc seemed to be a memory from another day entirely. Her phone was still cupped in her hand and her hand cupped in her lap. The bus was empty apart from two ladies near the front. Amy sat at the back. She could have called her mum right then but instead she closed her eyes in weariness and chose to speak to no one.

‘Mum?’ Amy still had the key to her mum’s house. She used it whenever she visited but never went beyond the threshold without making sure her mum knew she was there.

‘I’m out the back.’

Amy walked through the kitchen and out to the conservatory on the other side. Her mum sat with her back to the window and an open book on her lap. Outside, the sun was strong enough to backlight the clouds and fill the space with a hard grey light.

‘Mum?’ Amy repeated, quietly this time.

Geraldine smiled as she looked up but that faded as she saw Amy’s expression. She set the book aside, her fingers finding the bookmark and the side table in a single, fluid move. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘It’s Dad. He’s in hospital.’ Even after all the years they’d been divorced the mention of either parent to the other caused tension; usually a barely perceptible hesitation. They both tried to show nothing but Amy always picked up on it. This time, though, all she saw in her mum’s expression was the need for answers. ‘He’s had a heart attack. He’s conscious.’ She started to tremble. ‘It looks like he’ll be OK.’

‘When did this happen?’

‘I went to meet him for lunch. He was late but it turned out he’d collapsed.’

‘Why didn’t you call me?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t want to call anyone. It didn’t feel real and I decided I just wanted it to be me and him if . . .’ She didn’t finish the sentence; either she’d said enough for her mum to understand or else she’d already think that was as selfish as it had just sounded to her.

‘I understand why you didn’t phone immediately, Ames, but half a day later?’

‘You’re not married any more,’ she pointed out, then apologised. ‘They asked me for his next of kin and I didn’t know whether that was me, you or Nan.’

‘You as much as anyone, I suppose. Not me in any case.’

Amy took a breath. ‘He’s asked you to go.’

‘To the hospital?’

‘Dad said you and he had unfinished business.’

Her mum turned from Amy and stared into her small walled garden but not before Amy had seen the quick widening of her eyes. ‘Did he?’

‘What did he mean by that, Mum?’ Her mum had a strong profile, high cheekbones and features that were neat and in proportion. She was elegant and polished, the sort of woman that Amy thought would find it easy to attract a new man. Amy didn’t think she’d ever tried.

‘One of your dad’s jokes, I expect.’ Geraldine laughed lightly as if to prove the point. ‘Apart from that, I really don’t know.’

‘Will you go?’

‘Maybe.’ Geraldine swung her gaze back to meet Amy’s. ‘Do you want me to?’

‘I think you should.’ She almost added just in case. ‘See him tonight, Mum.’

‘I’ll go now.’

‘I’ll come with you.’

Geraldine squeezed her hand. ‘I can manage, Ames.’

‘I’ll see him first, Mum; I feel I should say goodnight.’ Amy smiled suddenly. ‘And warn him that you’ve actually turned up. I can get a taxi home afterwards.’ She squeezed her mum’s hand in reply. ‘I won’t be a fly on the wall, Mum. I mean, when was the last time you actually spoke to him?’

Geraldine shrugged, ‘I don’t know; I’ve blanked it out.’

* * *

Visiting hours had long since passed but Geraldine Buckingham hoped that compassion would win over red tape. She spoke quietly when she asked permission for them both to visit and the duty nurse seemed to run a critical eye over them before agreeing. ‘As long as he’s happy to see you,’ she replied, and then called Amy through as soon as she’d checked. Ten minutes later and it was Geraldine’s turn.

Robert lay propped up at a forty-five-degree angle. He didn’t look as frail as she’d feared but the drip beside his bed and the charts above it were enough to remind her how complicated their lives had become.

‘We’re not teenagers any more, are we, Gerri?’

She gave a wry smile and shook her head, ‘Too much water . . .’

‘And too many bridges?’ he said, ending a familiar sentence.

‘Exactly that.’ She pulled a visitors’ chair closer to the head of his bed. ‘Amy just told me what happened.’

He shook his head as if to say that it didn’t matter.

‘She said you wanted to talk to me.’

‘I said we had unfinished business.’ He pushed himself onto one elbow then up into a more upright position. ‘I remember feeling faint for just a second or two before I fell. I didn’t get sudden pain and didn’t know I’d hit my head even though there was blood.’

‘Did you know you had a heart condition?’

‘Does it matter? I’ve got one now.’

‘So you did?’

‘Blood pressure, that’s all.’ He brushed it away with his cannula-free hand. ‘Not enough to make me think morbid thoughts.’

‘But now you have?’

‘Exactly.’

Gerri could already see where this conversation would be heading. She clasped her hands together – it appeared casual but the fingers on one hand were gripping the others so hard that her knuckles had started to throb.

‘What are you planning?’

‘To tell Amy.’

‘Tell her what?’

‘Let me explain something to you first.’ He leant towards her further but she didn’t reach across to him. She felt her expression set and knew she was glaring. He refocused on the wall behind her and continued to speak. ‘What if I’d died? I never felt as though I was going to but I was drifting in and out and Amy was there. It’s not right that I could die without telling her the truth.’

‘But you’re not dying, Rob.’

‘But if I did . . . this is my wake-up call, Gerri. It’s what I meant by unfinished business.’

Geraldine’s anger rose swiftly. She stayed silent for several seconds as she tried to bite back the rage. ‘And you’re going to tell her what exactly?’ she hissed. She was trying to be quiet but her voice had risen to a loud whisper that stabbed the words at him.

‘Gerri, shush. You’ll get kicked out.’

She had no desire to do as she was told but didn’t want to be asked to leave either. ‘Amy doesn’t need this.’

‘Why not? She has nothing to occupy her apart from one dead-end job after the next. It’s 2014, Gerri. We’ve all been living with this for far too long. It’s got to stop now. Amy needs to know I never started that fire.’

‘You’ve told her enough times.’

‘She needs to know for certain. What have you told her?’

‘Nothing. It’s between the two of you.’

‘Does she ask you about it?’

Gerri pressed her lips firmly shut and shook her head.

He glared back at her. ‘Is that nothing or no comment? Because she has lived with this for over twenty years and she asks me questions all the time. Wants to know why we divorced. How can she believe that I’m innocent when she thinks the reason you left was because I was guilty? It’s illogical and she knows it.’

‘You were guilty.’ The words slipped out before Geraldine had a chance to check herself. ‘You wrecked our marriage and, if Amy knows the truth about that, how much respect do you think she’ll have left for you?’

‘I had a fling, I’m not saying “so what” but that isn’t the same as killing people, for God’s sake.’

‘An affair, which isn’t the same thing, Robert.’

‘You could have given me an alibi for the fire.’

‘It would have been a lie.’

‘Yes, but it would have led to the truth. You know I didn’t start it.’

‘It doesn’t matter. They had evidence, they made the case.’

Robert sighed and let his head drop back against the pillow. He stared up at the ceiling. ‘When I was first arrested you told me so often that you knew I was innocent. Do you even believe that any more?’ He turned to look at her. There was no frustration or anger now. He was serious and tired. ‘We’ve done each other some serious damage, Gerri. The worst betrayals.’

‘I know,’ she felt the tiredness too. ‘Of course I know you never killed them. I couldn’t prove it, t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...