- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

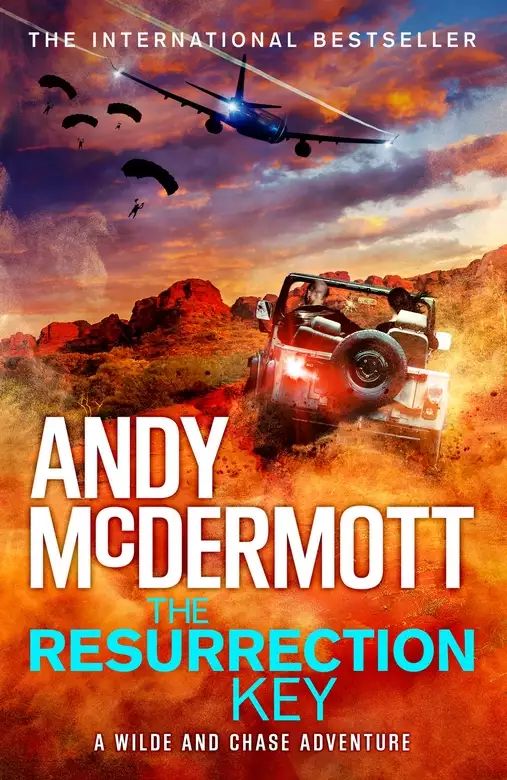

In the most thrilling instalment in the explosive Wilde and Chase series, the intrepid pair must race against time before a deadly power is unleashed on the world....

World-famous archaeologist Nina Wilde and her husband, ex-SAS solder Eddie Chase, think they have left their days of dangerous adventures behind. At home with desk jobs and daily routines, they are just like any other family. However, when an ancient and astonishing civilisation buried deep in the Antarctic ice is woken, Nina and Eddie must confront the gravest threat they've ever faced.

Travelling from New York to New Zealand, from the cities of Europe to the outback of Australia, they must try to understand the formidable power that has been unleashed. But pursued by shadowy mercenaries and sinister government spies, the clock is ticking before the entire planet is in peril....

Release date: September 19, 2019

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Resurrection Key

Andy McDermott

Prologue

The Southern Ocean

A frigid wind bit Arnold Bekker’s cheeks as he gazed at the ragged white peaks rising from the grey waters ahead. After six days at sea, the prospect of standing on solid ground was a blessed relief.

But the terrain ahead was not land.

The stark vista was an iceberg, a two-mile-long slab that had calved away from Antarctica. The research vessel Dionysius was on a mission that to most people sounded crazy; even those behind it, Bekker included, occasionally questioned their own sanity.

Their objective was to chart the berg officially known as D43 and test the feasibility of towing the entire colossal mass the three thousand miles to Cape Town in South Africa. If it could be done, it would provide the parched country with billions of gallons of pure, fresh water.

Crazy indeed. But if the plan paid off, it would not only save a nation from thirst, but make its backers a fortune. No risk, no reward, as Bekker’s fiancée liked to say. He agreed with the sentiment, but at the same time it drew a wry smile. He was the one freezing his balls off, while Imka oversaw the operation from a climate-controlled office back home . . .

He retreated into the relative warmth of the ship’s bridge. A plotting table was laid out with a large blow-up of D43’s most recent satellite photograph, two weeks old. The first task was to circumnavigate the iceberg to check for any more recent changes; a section breaking away, for instance, or a fault line developing. ‘Are we ready to start?’ Bekker asked.

The Dionysius’s skipper, Botild Havman, tapped at the picture’s edge. ‘We’re here. We’ll go around it clockwise, a kilometre out.’

‘Won’t that be too far to see anything?’

‘We’ll see enough. And we’ll be clear of most of the bergy bits and growlers.’

Bekker hid his amusement at hearing the terms for smaller ice fragments pronounced in a strong Swedish accent, and went to the windows. The iceberg filled his view, its various strata standing out clearly. The deepest submerged parts were at least a million years old, prehistoric snow compacted into ultra-dense blue ice. D43’s visible bulk was only about a tenth that age, but still ancient. If the plan worked, the residents of Cape Town could be drinking water from ice older than the whole of human civilisation.

Havman issued orders, then brought the Dionysius on a course paralleling the iceberg’s western flank. Bekker watched the great mass slide past. This close, second thoughts rose about the whole project. Would even a couple of repurposed supertankers, the only vessels theoretically powerful enough to tow such a colossal object, be enough?

He considered calling Imka over the satellite video link to voice his doubts, but held off. They had already spoken an hour ago, when the iceberg was first sighted, and the bandwidth was not cheap. Better to wait until he had something specific to report.

The ship continued around the berg. In places, surface snow had been washed away to leave a surreal landscape of glassy ice. D43 had partially rolled as it tore free of the ice cap, exposing strata of cyan and turquoise and deep blue. No photograph could have prepared him for the sheer beauty of the sight. Maybe Imka would regret staying in the warmth after all . . .

His entrancement was disturbed by a discussion between Havman and a crewman. ‘What is it?’ asked the South African.

‘Something odd on the radar,’ the captain replied. ‘Inside the ice.’

Bekker came to see. On the screen, the iceberg showed up as a ragged, fuzzy line to the right of the central dot marking the Dionysius’s position. The ice’s varying density accounted for the radar return’s diffuse appearance – but within it was a sharply defined shape. ‘What’s that?’

‘Don’t know,’ said Havman. ‘It’s solid, though. Rock – or metal.’

‘How could it be metal?’

‘Meteor, perhaps. Or a ship or plane.’

‘That deep in the ice?’ Bekker looked back at the swathes of blue – the product of time, far older than the couple of centuries since humans started to build their ships from metal rather than wood. But the shape on the radar screen seemed too symmetrical to be a mere rock, even one that had fallen from space. So what could it be? He let out a brief, involuntary laugh.

‘What?’ asked Havman.

‘I just wondered if it was a UFO. A spaceship,’ he clarified. ‘But that’s ridiculous. Isn’t it?’

Havman’s studiously blank expression spoke volumes. He regarded the radar screen again. ‘We might be able to see it soon. There’s an opening in the ice.’ He pointed out an indentation in the fuzzy line.

Bekker went to the windows – and saw it for real. ‘It’s a cave!’

Havman followed his gaze with binoculars. ‘A big one.’

‘We could probably fit the whole ship inside.’

Chuckles from the bridge crew. ‘I don’t think that would be wise,’ said the captain. ‘We could send in the boat, though. If that’s what you want to do. It will cost us time.’

Bekker took his point. But the cave was tantalisingly close . . . ‘We need to see what it is,’ he decided. ‘We are doing a survey, after all. How long would it take?’

‘Thirty minutes, perhaps.’ Havman checked the water. ‘Not too much floating ice. We can bring the ship closer.’

Bekker tried not to sound too childishly enthusiastic. ‘Okay. Let’s do it. If it’s nothing, we’ll carry on with the survey.’

‘As you wish.’ The Swede adjusted the Dionysius’s course.

The ship soon drew level with the opening. Bekker tried to see inside, but all he could make out were twilight-blue walls of ice. He went back to the radar. The object should have been in line with the entrance. ‘I can’t see it.’

Havman rechecked the screen. ‘It must be embedded higher up.’

‘We’ll definitely have to take the boat in. Maybe we can climb up to it.’

The captain cocked an eyebrow. ‘We? Mr Bekker, do you have any experience in ice climbing?’

‘No, but—’

‘You’re my client, but you’re also my passenger, so your safety is my responsibility. You hired people who know what they’re doing. Let them go.’

‘I suppose you’re right,’ Bekker reluctantly agreed.

The Dionysius heaved to, crewmen preparing its boat for launch while Havman and Bekker spoke to the man and woman who would make the trip. Wim Stapper was a blond Dutchman with the wiry build of an extreme sports enthusiast, while the Finnish Sanna Onvaan had short, fiery red hair and the strong upper body of someone who spent much time dangling from high places. Both were in their late twenties and expert ice climbers. They were as enthusiastic as Bekker about the unexpected side mission. ‘If it is a UFO,’ said Onvaan, grinning, ‘maybe we get to take selfies with space aliens!’

‘We don’t know if it’s a UFO,’ said Bekker. ‘If it’s just a big rock, then we’ll carry on with the survey. But,’ a smile, ‘if it is a spaceship . . . get lots of pictures!’

Havman shook his head. ‘You have all seen too many movies. Don’t get too excited – that is when you make mistakes.’

‘We will be okay,’ Stapper assured him as he zipped up his red coat. ‘We know what we are doing.’

‘Good. Then don’t take any risks, and stay safe.’

‘Risk is our business – and our hobby!’ said Onvaan cheerily.

The captain was unimpressed, but kept any further comments to himself. Instead he led the way to the ship’s tender, a bright orange thirty-foot rigid inflatable boat. Onvaan and Stapper boarded, then the RIB was lowered into the water and the pair set out, Onvaan at the tiller.

Bekker looked towards the cave. The waters were dotted with growlers, relatively small hunks of ice that nevertheless could weigh as much as a car. As with all icebergs, most of their mass was hidden beneath the surface, seemingly innocuous pieces becoming potentially shipwrecking obstacles. ‘Watch out for the ice, okay?’ he said into a walkie-talkie.

The retreating Stapper made a show of scanning the sea. ‘Ice? Ice? Oh, that ice,’ he said, gasping at the berg.

‘Funny. Okay, see what’s in there.’

Bekker watched the boat weave around the bobbing growlers towards the cave mouth, then he and Havman returned to the bridge. ‘What’s it like?’ the South African asked as the RIB slipped into the shadows.

The reply was surprisingly distorted considering the short range, a crackle behind Stapper’s words. ‘Everything is blue, very beautiful.’

‘Can you see the thing in the ice?’

‘A bad choice of words if you have seen the movies I have!’ The Dutchman laughed. ‘We are coming out of the entrance tunnel . . .’

A long silence. ‘Wim? Are you still there?’ asked Bekker, concerned.

The reply was prefaced by another laugh – but one of nervous disbelief rather than humour. ‘Yes, yes, we are here. And so is, ah . . . You know we were joking about a UFO?’

‘Yes?’

‘I think . . . that is what we have found.’

The silence this time was on Bekker’s part. ‘Are you joking?’ he finally managed.

‘No, no, I’m not! It’s inside the ice, stuck in the cave wall. It is metal, and . . . big. As big as a plane. I am not kidding you,’ Stapper added, pre-emptively.

‘It really does look like a UFO,’ Onvaan added in the background.

‘It’s hard to tell exactly, but I’d say about . . . a third of it is out of the ice?’ Stapper went on. ‘It’s at an angle. There are windows near the front. They look like eyes.’

Bekker practically heard the shiver in the other man’s voice as he realised what he had just said. ‘Can you get to it?’

‘Yeah, yeah. The cliff climb looks easy— Oh!’

Both Havman and Bekker flinched. ‘What is it?’ demanded the captain.

‘I see a way in! There is a hatch in the side.’

‘We can reach it, no problem,’ said Onvaan.

‘I don’t know,’ Bekker said, misgivings growing. Assuming this wasn’t some dumb joke by the climbers – and he didn’t think their acting ability was up to it – then they had found something unknown. And the unknown could be dangerous. ‘Take pictures, then come back. We need to see what we’re dealing with.’

‘No, no, it will take two minutes to climb to the door,’ replied Stapper. ‘We can’t come this far and not look inside!’

Frustrated, Bekker looked to Havman for support. ‘If they were my crew, I would order them back,’ said the captain. ‘You are their boss.’

‘Yeah.’ He spoke into the radio again. ‘No, get back here. Or . . .’ He halted, aware there wasn’t anything he could threaten them with short of being fired, and then the expedition would be over before it even began. ‘Just get back to the ship.’

The lack of a response meant the pair were either ignoring him, or already climbing the ice wall. ‘Pielkop!’ he muttered.

The walkie-talkie remained silent for a few fraught minutes, then crackled to life. ‘We are at the door,’ said Stapper at last. The distortion was worse than before. ‘It’s big, nearly three metres high. It opened when Sanna touched a round thing on it. We’re going in.’

Bekker sighed in resignation: they were entering with or without his permission. ‘If there’s any danger, get out and come back to the ship.’

‘We will. But the ice is solid. I don’t think—’

The Dutchman was abruptly cut off by a harsh caw of static. ‘Wim?’ said Bekker. ‘Wim, can you hear me? Wim!’ No answer. ‘Shit!’

Havman marched to the helm. ‘I will bring the ship closer. If they are in trouble, we can reach them faster.’

‘Good, okay,’ Bekker replied, before trying the radio again.

There was still no response.

‘Why did you let them go in?’ demanded Imka Joubert over the satellite link. The video quality was low and glitchy, the computers at each end straining to make the most of the parsimonious bandwidth.

‘I told them not to!’ said Bekker. Thirty minutes had passed since his last contact with the explorers; he had called his fiancée as much to vent about the situation as report on it. ‘This is what happens when you hire thrill-seekers – they go seeking thrills!’

‘When I hired them?’

‘Okay, when we hired them! But we lost contact when they went inside this thing, and still haven’t heard anything from them.’

‘What is this thing?’ Imka asked. ‘What did you find?’

‘I don’t want to say on an open channel. Let’s call it an . . . old ship.’

‘What, like a sailing ship?’

‘I’ll tell you more when I can set up an encrypted link.’

A disbelieving laugh. ‘You really think anyone is eavesdropping?’

‘I don’t want to take any chances. Trust me, Imka.’

‘I do. Otherwise I wouldn’t have let you go down to the bottom of the world, would I?’

He chuckled. ‘You want to swap places? You’re the one who knows all about ships . . .’

‘I’m fine here, thanks. Did I mention it’s twenty-two Celsius today?’

‘No, and I wish you hadn’t. But the Dionysius isn’t equipped for salvage work, so we’d have to—’

He stopped at a sudden rasp from the radio. Havman snatched it up. ‘Hello, hello!’ he said. ‘Are you all right?’

An ear-shredding screech of static – then a voice pierced the distortion. ‘Het heeft haar gedood! Het heeft haar gedood! Mijn God, help me!’

‘It’s Wim!’ said Bekker, jumping up in alarm. His native Afrikaans was very similar to Dutch, and he knew exactly what Stapper was saying: It killed her! It killed her! My God, help me! ‘Wim, what happened? What killed her – what happened to Sanna?’

The crew reacted in shock.

‘Help me! Help!’ came the panicked reply. ‘Oh God, it’s coming after me!’

‘What is?’

‘De demon! Sanna woke it up! It—’

Stapper’s words were cut off, not by static but a loud thump, followed by banging sounds. He had slipped, skidding down an icy slope – then came a pained shout as he hit something. But it was not the only shout. In the background was another voice, with a strange, throaty echo to it that barely sounded human.

Then the channel fell silent.

‘Wim!’ yelled Bekker. ‘Wim, can you hear me? Wim!’ He turned to Havman. ‘We’ve got to help him! We need to get into the cave. If you launch the lifeboat—’

‘Are you mad?’ said the Swede. ‘There’s a murderer running around!’ He hesitated, then with clear trepidation issued orders to the crew. ‘We’ll take the whole ship inside,’ he told Bekker. ‘We’ll be protected while we look for him.’

The Dionysius’s engines came to life. Bekker stared fearfully at the shadowy cave mouth, then belatedly realised that someone was calling his name. ‘Arnold! Arnold, what’s going on?’ said Imka over the satellite link.

‘Imka, something’s happened,’ he replied. ‘Wim and Sanna are in trouble.’

‘What kind of trouble? What—’

‘I’m sorry, I have to go. I’ll call you back as soon as we’ve found them. I love you.’

‘I love you too. But—’

He ended the call and rushed to the windows. The ship quickly closed on the iceberg. Dull thunks echoed through the hull as the prow struck bobbing growlers. The entrance loomed ahead. ‘Will we fit?’

‘We’ll fit,’ said Havman grimly. ‘Try to get him on the radio.’

Bekker called Stapper, to no avail. The captain slowed, bringing the Dionysius into line with the cave’s tall but relatively narrow mouth. The South African watched – then suddenly remembered something. ‘He said “it” . . .’

Havman didn’t divert his gaze from the icy passage. ‘What?’

‘Wim said “it” killed Sanna, not “he”.’

‘He was panicking. People say the wrong words when they panic.’

‘But he said it several times. “It” killed her, “it” was coming after him. And there was something else. He called it “de demon” . . . the demon.’

The temperature on the bridge seemed to drop as its occupants exchanged worried looks. Havman was the first to speak, standing straight and resolute. ‘It doesn’t matter. All that does matter is that we rescue him.’ He eased the Dionysius into the gap.

Bekker tensed, but Havman guided the ship cleanly through the cave mouth. The change in lighting from the stark whites and blues outside to sapphire-tinted gloom rendered him momentarily blind; he blinked, trying to take in his new surroundings as the four-hundred-tonne survey vessel slipped into the mysterious cave.

Shadows swallowed it.

‘There! I see something, five degrees to port!’

Ulus Cansel, captain of the freighter Fortune Mist, stared intently through his binoculars. The ship had been halfway through its voyage between New Zealand and Cape Town with a cargo of frozen lamb when it received a weak distress call. A nine-hour diversion at full speed had brought it to the source, but now the signal, from the RV Dionysius, had fallen silent. Cansel had been a mariner for almost thirty years; he knew all too well that that was a bad sign. The Dionysius had almost certainly sunk.

But that didn’t mean there weren’t survivors. A spot of colour against the grey sea had caught his eye: a man in a red coat, huddled on a chunk of floating ice. ‘Man overboard! Mr Figueroa, Mr Krämer, launch a lifeboat.’ The crewmen hurried from the bridge.

The Cypriot surveyed the surrounding waters. There was a large iceberg a few kilometres distant. The glossy sheen of raw, snow-free ice over much of its surface told him it had recently rolled; had the Dionysius been crushed by it?

He wouldn’t know until they completed a wider search, but the priority was recovering the survivor. An order, and the Fortune Mist’s horn sounded. At first the figure didn’t move, leading Cansel to fear he was dead, but then he shifted slightly. ‘He’s still alive!’ the captain called out. ‘Get him aboard, quick!’

The lifeboat reached the floating ice.

Jakob Krämer regarded the stranded man warily. The floe was only small, and the lean German was sure it would pitch over if he climbed onto it. ‘Hey! Can you hear me?’ he shouted in English.

No response. He asked the same in his native language, but the man remained still. ‘Hold us steady,’ he told Figueroa. ‘I’ll pull him closer.’

He manoeuvred a boat hook to snag the man’s coat. Straining, he pulled him across the ice until he was almost within reach. The floe rocked, bumping the lifeboat. Krämer cursed, then stretched out as far as he dared. His gloved fingers caught fabric; he clutched it tightly and hauled the unconscious man to the boat’s side.

The ice tipped again, sending a freezing splash over the man’s legs. He flinched, but his rescuer now had a firm hold. Figueroa joined in, and they brought the limp figure aboard.

Krämer examined him. The man was young, his face pale from the cold. If he had spent much longer exposed to the elements, he would be dead. ‘Get us back to the ship, fast,’ the German said. Figueroa returned to the outboard and brought the boat around. ‘We got you,’ Krämer said, trying to reassure the survivor. ‘You are safe.’

The man’s eyes snapped open. The sailor felt a sudden unease; he was looking through rather than at him, the gaze almost manic in its terrified intensity. ‘Demon . . .’

Krämer blinked at the feeble whisper. ‘What?’

‘Demon . . .’ the man in red repeated. His accent sounded Dutch. ‘In the ice. Sanna woke it . . . it killed her! We took the key. We took the key!’

Krämer realised his passenger was clutching something tightly to his chest. He looked more closely – and saw a glint of metal.

Gold.

‘We woke the demon,’ the young man went on. His breathing quickened. ‘It killed Sanna – killed everyone!’

Krämer was more interested in what he held than his words. Demons? His near-death had obviously driven him mad. He shifted to block Figueroa’s line of sight with his body, then started to prise the man’s fingers open.

‘No, no!’ gasped the Dutchman. ‘The key – don’t give it the key!’

‘We will be at the ship soon,’ said Krämer loudly, trying to drown out his voice. He finally forced the young man’s hands apart and tugged the object free. ‘It’s okay.’

‘No!’ he cried again. ‘They killed, they . . .’ He slumped in exhaustion.

‘It’s okay,’ Krämer said again, giving Figueroa a surreptitious glance before examining his prize.

What it was, he had no idea. It certainly didn’t look like a key. A plate-sized metal disc, its central hub inlaid with a circle of polished purple stone, into which was set a large crystal. At first he had thought the object was gold, but now he saw it wasn’t quite the right colour, with a distinctly reddish tinge. Writing was inscribed in its surface, but he didn’t recognise the language.

He turned it over. Both the stone and the crystal continued all the way through its centre. More unknown words ran around them.

One symbol was unmistakable, though.

A skull.

It faced to the left, jaw open as if shouting. It was oddly deformed, the back of the head elongated. Something about it unsettled Krämer. Maybe the survivor’s ravings about demons had got to him . . .

He shook off the thought and hid the object inside his coat. Even if the gold wasn’t pure, its weight told him it was still worth a lot of money. And the only other person who knew about it was a madman, in shock from his ordeal. He wouldn’t be believed. No, you didn’t have anything when we found you. You must have lost it in the water. Sorry.

The German pulled his zipper back up. He felt no guilt about what he had just done: the man was still alive, wasn’t he? That was worth more than any piece of treasure. And it gave Krämer the chance to escape from the drudgery of life aboard a freighter. He knew of places online where such salvage could be sold, with no awkward questions asked. A few months from now, his life could change for ever.

He smiled at the thought – then looked down in alarm as the man stirred. ‘We’re at the ship,’ he said hastily. ‘You’re safe.’

‘No, not . . . safe,’ came the weak reply. ‘More demons. Sleeping in . . . the ice.’ His hands searched for the object with growing desperation. ‘The key! Where is it?’

‘I don’t know,’ replied the German. ‘You must have lost it in the water.’

‘No, I had it! Listen!’ He suddenly clawed at Krämer’s coat, pulling the startled crewman closer. ‘The key – it wakes them. Sanna woke one. It . . . it killed her, killed everyone on the ship! If they wake, they’ll kill us all!’ His voice rose to a shout. ‘The demons will kill us all!’

1

New York City

Four months later

Professor Nina Wilde paused for dramatic effect as she regarded her students, then spoke. ‘My first rule of archaeology: no find is worth risking your, or anyone else’s, life over.’

That aroused surprise from her audience. ‘Yes, I know that may sound weird, from someone with my track record,’ she went on. ‘But I’m speaking from experience – very, very painful experience. I’ve lost count of how often I’ve almost been killed out in the field, and a couple of times in my own home. But I’ve forced myself to keep a very good count of the people who actually were killed because of my discoveries. And it’s too many. Which is why I’m talking to you in a lecture hall rather than chasing around the world after legends.’

‘But you’ve found so many,’ said a young woman. This early in their first semester, Nina hadn’t yet memorised all her students’ names. Madison?

‘Yes, I have – but I wanted to leave some for you to find as well.’ Some laughter at the joke, which was a relief. It was only the redhead’s second year in her academic role, and she still found balancing research and teaching hard. ‘I hope I’ll inspire you to make your own discoveries. But I also want you to learn from my mistakes.’

‘What mistakes?’ asked a man – a boy; God, they were all so young! – she was fairly sure was called Aiden.

‘I used to think it was my job, my duty, to bring lost wonders back to the world,’ Nina told him. ‘Which I did. Atlantis, the tomb of Hercules, El Dorado, Valhalla, the Ark of the Covenant . . . and more besides.’

‘It’s a very impressive list.’ She remembered this youth’s name: Hui Cheng, a student from China. Her concern that he had won admission to the university based solely on his wealthy parents’ bank balance had already been assuaged by his work, breadth of knowledge and drive.

‘Thank you. But it came at a price. It seems like every discovery I made had some madman, or occasionally madwoman, after it for nefarious ends. And I don’t just mean tomb raiding for money. I’ve faced people trying to start wars, take over countries, nuke cities . . .’

‘You didn’t talk about this in your books,’ said Aiden dubiously.

‘My books are about the actual archaeology. If you want explosions and gunfights and car chases, you can always watch the ridiculous movies based on them!’ More laughter. She let it subside, then continued, more sombrely: ‘But the antimatter explosion in the Persian Gulf three years ago? That was caused by something I found. When Big Ben in London collapsed? Again, caused by one of my discoveries. The religious cult gassed in the Caribbean, the skyscraper destroyed in Tokyo – all ultimately my responsibility.’

‘But you weren’t personally responsible,’ said Cheng. ‘The incident in Antigua, you’d been kidnapped! You didn’t have a choice.’

‘They wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t been involved,’ Nina insisted. ‘My thought process at the time was: I can find these things, so I must find these things. I never considered whether I should find these things.’

‘So . . . you wish you hadn’t found them?’ Madison asked. ‘You think your whole career’s been a mistake?’

‘No, but I think I’ve made mistakes. The lesson they’ve taught me is actually my second rule: think before you dig. Before you put the tip of your trowel into the ground, ask yourself some very big questions. Am I the right person to make this discovery? Am I doing so for the right reasons? And most of all, do I have the ability to protect this discovery? If you can’t truthfully answer yes to all three, then you should hold off. Always remember that your actions will make you a part of history too – and you want it to look favourably upon you.’ She cast her gaze across her students, one by one. ‘What I’ve come to realise is that you need great wisdom to know if you should return an ancient wonder to the world. Even after everything I’ve experienced, I’m still not sure I have that wisdom.’ A pause, then, with dark humour: ‘And I’m damn sure none of you do.’

She knew that would not go down well. Most of the young men and women limited their affronted responses to facial expressions, unwilling to challenge a professor, but there were inevitably a few vocal objections. ‘I don’t think that’s fair,’ said Aiden. ‘You don’t know us.’

‘No,’ Nina replied, ‘not as individuals, but I’m forty-five, and by now I know people. You’re all, what? Eighteen, nineteen, twenty? That’s an age where in many ways I envy you – the whole world’s just opened up, and you can do anything. You can even bend down without your back hurting! Damn, I miss those days.’

The humour helped ease the tension. ‘But,’ she continued, ‘while you’ve got limitless energy and enthusiasm, you don’t have experience. And I can tell you, ironically enough from experience, that when you’re young, if someone tries to give you the benefit of their experience, you’re all like “yeah, whatever, grandma”. I was the same! And unfortunately, that got me into trouble – trouble that affected other people. If I’d realised what I was getting into, I would have done things differently. Or possibly not at all.’

‘But then everything you’ve discovered would have remained lost,’ said Cheng. ‘Our knowledge of ancient history would be incomplete. It would be wrong.’

‘It would, yes. But that goes back to my first rule – is that knowledge worth the lives lost to uncover it? All of you, take a look at each other.’ Nina waited for them to do so. ‘Now, if you thought you were on the verge of making an amazing discovery, but you knew that in doing so you’d be directly responsible for the deaths of some of your classmates . . . would you still do it?’

The question aroused discussion. Cheng was first to reply. ‘But that’s a flawed premise, Professor.’

She arched an eyebrow. ‘Is it now?’

‘It assumes we have accurate foreknowledge of the future, which we don’t. You can only make decisions based on the information you have at the time. We can’t know that any of us will die.’

‘Experience helps you with risk assessment, though. Crossing the street? You’re probably safe. Going into a region of the Congo jungle controlled by warlords? Not so much. And that wasn’t a hypothetical. I did it – and it was a mistake, a terrible one. I hope none of you ever do the same.’

The room fell silent for a moment. Again Cheng spoke first. ‘I have a hypothetical I’d like to put to you, Professor.’

She nodded. ‘Go on.’

‘Suppose you believed you had evidence of a civilisation millennia older than anything currently known. The evidence isn’t yet definitive enough to convince mains

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...