There was a time in my teenage years when I remembered everything. I didn’t bother revising for my exams because I was one of those kids. The smart-arses. The little sods who somehow got by, despite spending around forty per cent of class time trying to ping a rubber band or hair tie off the head of whoever was sitting at the front. By the summer, I’d be doing an exam in the stifling gym, and able to recall with perfect clarity something that Mr Rodgers had waffled on about five months previously.

That was only the start. I could remember the directions to get to places, even if I’d only been there once – and long before Google Maps turned everyone into a cheat. I’d know the birthdays of all my friends and family, plus I could reel off song lyrics for entire albums, even if they’d only just come out. Memory was my superpower.

And now…

Now, I can barely remember the day of the week. I spent last year thinking I was forty-two when I was, in fact, forty-one. Last week, I went to IKEA and forgot where I parked the car. I went to the security office and said it had been nicked, only to find out I’d parked two rows away from where I’d been searching. Even then, I walked past it twice before the officer pointed to my car and asked if it was mine.

Today’s aberration is that, once again, I didn’t pick up the bags for life before heading into the supermarket. Every time I get to the checkout and have to pay seven pence for a new bag, it kills a tiny bit of my soul.

It doesn’t help that today’s plastic bags are thinner than Polly from three doors down after she had the gastric band fitted. As I heave my shopping into the back of the car, placing them on top of the unused bags for life, it feels as if I’m running a dangerous grocery gauntlet. Nothing says sophisticated, mature adult like chasing an escaping tub of Caramel Chew Chew Ben & Jerry’s across a car park.

I’m not sure what it is that catches my attention. Maybe there is some sort of noise, or perhaps it’s one of those corner-of-the-eye movements that later feel as if they were never really in view. But something makes me glance across to the recycling banks in the corner of the car park. They are a pair of scratched, metal monstrosities; the type of things that always have clothes or shoes littered around the base. Nobody ever remembers them being installed, as if they’ve eternally occupied the same spot.

It’s one of those December days when it doesn’t feel as if the sun has fully risen. The murk makes it hard to see, but I can make out two lads by the bins. One is broad and tall. He looms over the other like a bloated giraffe next to a gangly, bulimic goat. They’re at that awkward mid-teen time where it’s not easy to guess an age. Some have shot up to six-foot-plus by their fourteenth birthday, while an unlucky few still talk with a high-pitched squeak at seventeen. Some in their twenties continue to be peppered with spots, but there are also fifteen-year-olds with stubbly beards.

You see everything as a private tutor.

The slap happens so fast that it is like I hear it before I see it. There’s a crack and the larger boy’s hand whips across the other’s face. The smaller boy reels sideways and bounces off the side of the recycling bin. I’ve taken a few steps towards them before I realise I’ve moved. Pure autopilot. I recognise the taller boy now I’m a little closer. I should have known him from the height alone. Josh is in the year below Katie at school. He’s fifteen or sixteen but already the size and shape of a fully-grown man.

‘Hey!’

I shout across and both boys turn towards me. I don’t recognise the smaller of the two but he’s half hunched, anticipating another blow. Josh has a hand paused in mid-air. The smaller boy catches my eye momentarily but he isn’t stupid enough to hang around. He only needs a second – and he takes it, turning and dashing past the bins into the trees beyond. By the time Josh realises what’s happened, he’s left spinning on the spot, looking between me and his escaping adversary.

I’m only a few steps from the recycling banks now, almost lost in the shadows of the surrounding trees in the corner of the car park.

‘What’s going on?’ I ask.

Josh squints down, trying to place me. He’s one of those local kids that I know solely through reputation. It’s hard to miss a boy who’s already over six foot. I’d guess many in the area know him by sight alone.

‘None of yer business,’ he replies.

‘You can’t go around hitting people.’

‘It’s nothing to do with you.’

A shiver passes through me and though there’s a chill to the air, I’m not sure it’s that. It feels like I’ve missed something that was in plain sight.

Josh has turned towards the woods, in the direction the other boy scuttled – and I’m left standing awkwardly, unsure into what I’ve just interjected myself, or what else I could possibly say.

I head back towards my car, where the door is still open and my shopping sits untouched in the boot. I push everything towards the back, wedging the bag with the yoghurts into the arch so that it can’t escape, and then close the hatch.

I’m about to get into the driver’s seat when I notice the woman loading shopping into the 4x4 a few spaces down from mine. The thing with places like Prowley is that everyone grows old together. Sharon Tanner was in my class at school three decades ago. We’ve never been friends, and probably not even at the level where we might nod to one another on the street. I would guess we’ve seen each other once a week or so for all those years – but barely swapped a word.

Sharon is strapping a toddler into a child seat on the passenger side of her vehicle. I can hear her muttering something, though it’s too quiet to make out anything specific. She’s in a Sports Direct special, some sort of cheap pink-and-green tracksuit, even though I doubt she’s seen a track in her life.

I shouldn’t judge.

After fastening in her child, Sharon steps back from the car and starts to turn towards her shopping, which is on the tarmac at the back of her vehicle. She stops when she sees me staring and returns the look with a mix of confusion and defiance.

‘What?’ she says.

I nod towards Josh, who is ambling across the car park towards us. His hands are in his pockets and his head dipped.

‘I saw Josh,’ I say, hesitating over the words.

Sharon turns to take in her son and then looks back to me. ‘So?’

‘He, um… I saw him hitting another boy over there.’

I motion towards the recycling bins across the car park. By this time, Josh has reached his mother’s 4x4. He leans on the back window and stares at something on his phone. It’s hard to tell through the gloom but it looks like he rolls his eyes.

There’s a silence, punctuated only by the sound of a revving engine from the far side of the car park. These are probably the most words I’ve said to Sharon since we left school all those years ago.

I see some sort of annoyance in the narrowing of her eyes but it’s hard to tell who it might be for.

‘That true?’

Her reply is spiky, and, though she doesn’t turn her head, it’s somehow clear she is talking to Josh. She continues to watch me as Josh shrugs a silent response. There’s no way his mother could have seen it but she still knows.

‘Get in the car,’ she snaps – and, perhaps surprisingly, her son immediately does as he’s told.

There is a gap of a few seconds and then Sharon picks up a shopping bag from the floor. She pushes it into the back of her car and then wedges in three more bags before closing the boot.

I’ve not moved, though it’s hard to know why. I have no idea what to say next, if there’s anything to say at all.

Sharon walks to the driver’s side door and then stops to turn to me.

‘Jennifer Owen,’ she says, almost as a hiss.

My old maiden name. I have an urge to tell her it’s ‘Hughes’ now, even though Bryan and I are separated.

‘You should mind your own business,’ she adds quickly.

‘I wasn’t trying to get involved. I saw him hitting another kid, he’

Sharon offers a shrug that matches her son’s. ‘So? It’s nothing to do with you. Besides, it’s not like Katie’s perfect.’

I’m not sure exactly why it happens but the mention of Katie’s name feels like a slap in itself. Perhaps it’s because I have no idea why Sharon would know my daughter’s name.

My arms seem to have folded themselves across my front. ‘What do you mean by that?’ I reply.

I get a snarling smirk as a response. The type of expression that says so much more than any words could do. I feel momentarily lost until Sharon speaks again.

‘How about you look after your own kids and I’ll look after mine,’ she says.

If I have anything to say, then it’s caught at the back of my throat. By the time I might get anything out, it’s too late because Sharon’s already in her car and she closes the door with a slamming thunk.

It’s only as she reverses out of the space that I realise we have an audience. There are seven or eight people dotted around the nearby spaces watching everything that’s just happened. I feel myself shrinking as I glance to the tarmac to avoid any stares and then cross back to my own car. I fumble the handle, trying to get inside and away from the accusatory stares. People might pretend otherwise but everyone loves a good public argument. There’s nothing quite like free, live entertainment to cheer everyone up a couple of weeks before Christmas.

I reverse out of the space and drive past the petrol station. I’m not sure why I feel so shaken by a few cross words but it’s hard to escape the sense that Sharon was right about one thing.

Perhaps I should mind my own business.

Another day and the combination of potholes and rain from the past week or so has created pulsing rivers along the edges of the dark country lanes that surround Prowley. I weave across the barely visible central line in an attempt to stay out of the deepest trenches but there’s no avoiding the worst of it. Spiky jolts of pain fire along my back and neck as the car lurches into an unseen crevice and bounces back up onto the main surface.

The council never seems to do anything about the craters that appear in the local roads – and it doesn’t help that there are huge slurries of mud to avoid as well. Those come from one of the multitude of local tractors that seem to hold up traffic whenever I’m in a rush and trying to get somewhere.

Gosh, the middle-class perils we have to endure.

One of those newish Christmas songs that will be forgotten by next year is on the radio. The end is interrupted by the DJ, who tells everyone that it’s seven o’clock, which means it’s time for the evening news. There’s some sort of political upheaval going on but that could be the news for any day out of the last few years. There’s always something.

I pass the ‘Thank you for driving safely’ sign and ease around the next bend. I’m now out of Prowley and there’s a good few miles of overgrown hedges and narrow country roads before I reach anything close to mass civilisation. There are only a handful of farms and remote houses this far out of town – but that doesn’t stop me having to swerve around a wheelie bin that’s been left too far away from the verge and not brought in by the homeowner. I spot it at the last second and curse under my breath as I slosh through a mini lake on the other side of the road. It’s a good job nobody was driving the other way.

Driving along these roads is pure muscle memory. I’ve been doing it for so long that I know instinctively when to start slowing for the next bend. I ease onto the brake and take the turn onto Green Road, which will take me almost to the college.

I’m starting to accelerate when my phone dings with a text. I glance down to the well next to the handbrake where the phone’s screen is momentarily illuminated before fading to dark again. I didn’t see who’d messaged me but it’s likely Katie. I’m late picking her up from football practice – and she won’t be happy. I was busy bunkering down on the sofa with a Fruit & Nut when I remembered I was supposed to be collecting her. It doesn’t help that it’s so cold and wet. She’ll be fuming.

The engine roars as I press harder on the accelerator. A mist of light rain appears across the windscreen – and I’m probably at least ten minutes from the college. Katie has every right to be annoyed.

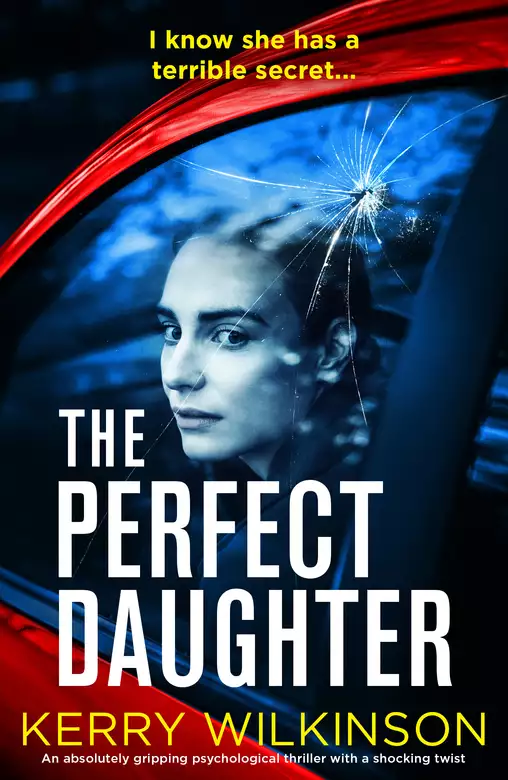

I take the next bend and then my phone pings a second time. Everything happens in the same instant. I glance down to my phone, where the screen has flashed white with a name I can’t quite make out. I reach for it but, in that precise moment, there is a crunching thump from the front of the car. It’s reflex as I slam on the brakes. The car slides sideways and there’s a point in which a hedge is directly in front of me. I’m not sure what I do – it’s certainly nothing conscious – but I must twist the steering wheel back the other way as the car swerves onto the correct side of the road. It slides a little further on the slick surface and then rolls to a stop.

It’s only when I next exhale that I realise I must’ve been holding my breath the entire time. The tightness bristles in my chest as the windscreen wipers continue to flash back and forth with a gentle squeak. I stare ahead as the beam from the car’s headlights disappear into the grim blackness of the night.

There’s nothing out there.

I’m frozen; my hands squeezing the steering wheel, foot pressed on the brake. It takes me a few seconds to remember to put the car in neutral. Even then, the car rocks backwards a little until I wrench up on the handbrake.

A third beep of my phone has me yelping with surprise. I look down to the well again – and Katie’s name is clear this time – but I ignore her and stare out into the darkness.

I must have hit a bin.

People keep leaving them out on the edge of their properties and, this far away from town, there is no pavement. They rest on the grass verge, or the side of the road itself, often until the next day.

Stupid, lazy, stupid people.

I press the red triangle in the centre of the console and the orange hazard lights start to flash at the front and back of the car. In the muddle of the last minute or so, I try to get out of the car without taking off my seat belt. The cord slices into my breastbone as I open the door and strain against it before realising why I can’t move. Everything is a jumble. I unclip the belt and then grab my phone.

Out of the car and the rain is harder than I realised. More of a rippling head-basher than a mist. I pull up the hood of my jacket and then crouch to check the front of the car. The moon is blurred by the grim clouds but my car is silver and there’s enough light from my phone to see any darkened scuffs. I’m expecting some sort of deep dent, perhaps even a broken headlight but, as best I can tell, the only mark on the front is a soft graze. It’s nothing new: the mark came courtesy of a pillar in a multistorey when I was trying to reverse out of a space. Those pesky unmoving pillars.

I run a hand across the wing but come away with nothing but a wet palm. Aside from the scratched indentation that was already there, it doesn’t feel as if there’s anything else.

That’s one thing, at least. There’s still another four months until the car is paid off. There are already enough bills to pay with Christmas around the corner – plus spending hours on the phone with an insurance company is as appealing as watching anything presented by Piers Morgan’s smug plasticine face.

I take a step away from the car and stare back towards the way I’ve come. It’s only now I’ve stopped that I remember Bryan lives somewhere around here. The woman with whom my ex-husband is now shacked up has one of these houses out in the sticks. I’d recognise it in the daytime but some of the entrances to people’s driveways are hidden by the hedges. At night, it’s hard to tell where anything is.

Must’ve been that bin.

Must’ve been.

I move back towards my car and then figure I should check I haven’t spun the bin further into the road. It was bad enough that I clipped it but it could cause serious damage to someone else if it’s now in the middle of the lane, especially at night.

There’s a large puddle at the edge of the road, so I edge around that before continuing back down the street. A stream is flowing across the tarmac at one point, pouring from a field on one side across to the gully on the other. There’s always flooding around this area through the autumn and winter; always some reporter on the local news standing in a field with water up to his knees talking about how wet it is.

I walk for thirty seconds or so but there’s no sign of a bin in the road. I stop and turn back towards my car along the lane, its hazard lights winking into the darkness.

The only sound is the pitter-patter of rain on ground and, for the second time in as many days, a shiver goes through me. There is no one here and I feel alone and exposed out here in the open. I wonder if I perhaps clipped a parked car’s mirror, except there’s no sign of anything. Aside from my own vehicle, the road is clear in both directions.

I’ve already taken a step back towards the car when I see it.

It’s down in the gully, where the hedge meets the sodden grass before it becomes the road. I think it’s a crumpled bin bag at first. I almost carry on walking but there’s something about the shape that sets the hairs on my arms standing.

Her hair is splayed wildly; her knee bent at an abnormal angle to the way it should be.

It’s the Sports Direct special that gives it away. That cheap pink-and-green tracksuit.

Sharon Tanner lies unmoving in the gutter, her body crumpled by my car.