My mother doesn’t recognise me.

She’s on the other side of the café, almost hidden behind her MacBook. She sips her cappuccino, then puts it down and frowns at the screen as if whatever she’s looking at is in a foreign language. Her eyes narrow and her nose twitches, then she sucks in her right cheek but not the left. I wonder if I do that when I’m concentrating. It’s a long, long time since we saw one another and there’s that whole nature-nurture thing.

How much of her is me?

I’m trying to think of the best thing I could say to her when she looks up from the computer, catching my eye before I can turn away. She smiles in the way people do when they realise they’re being watched. Lips together, only the merest of upturn and then she focuses back on her laptop. She’ll give it a couple of seconds and then check on me once more, making sure I’m not some maniac stalker.

There’s no recognition there.

The waitress chooses that moment to drift by, picking up my empty teacup and saucer. She’s somewhere around my age – late-teens or early twenties, slim with long red hair, freckles and an apron tied tightly around her.

‘Would you like anything else?’ she asks.

She sounds perfectly polite but has that passive-aggressive ‘paying customers’ vibe about her. It’s not as if the café is busy. There’s only my mother, me and a gossipy part mothers’ meeting, part crèche at the back by the door to the toilets.

I ask her about the teas they have and then settle on an Earl Grey. She’s about to turn back to the counter when I point towards my mother.

‘Can you tell me who that is?’ I ask.

The server turns between us. ‘That’s Sarah.’

‘She’s the boss…?’

‘Right. If you’re after a job or something, I can get you a form…?’

‘No, I was curious. That’s all.’

She gives me a glance as if to say ‘weirdo’ without actually saying it, then she disappears back behind the counter with my empty cup. I quite like the level of disdain she manages to conceal under a mask of politeness. Takes a blagger to know a blagger, I reckon.

I wonder what my mother is working on. Perhaps the accounts for this place, or a new version of the menu? I watch her in a not watching her kind of way. She never leaves my peripheral vision as I look through the large window at the front of the café towards the street. There are a couple of empty tables out there and someone walking their dog.

The espresso machine is made from shiny aluminium, which makes it a pretty good mirror as I manage to keep an eye on her while facing the opposite direction.

It’s hard to work out whether she looks like me. Her hair is a brighter blonde than mine but it has that almost white shade of bleach. Our noses are similar, slim and narrow, rather than squashed. I’m not sure beyond that. Her taste in clothes is brighter than mine. I went black and have never gone back; she’s in a floaty, summery sunflower yellow dress that would look awful with my pale skin. She either has a fake tan or has been on holiday recently.

There’s a burbling of liquid from behind the counter and then the waitress reappears with my drink and a smile. The napkins have been printed especially, with a logo that reads ‘Via’s’ in the corner. I fumble through my purse for some pound coins and apologise my way through paying, then go back to watching my mother.

She’s a two-finger typist, one of each hand, like one of those drinking bird toys that bob back and forth on a pendulum. Not technology-illiterate, more technology-befuddled.

There’s not much between us – a few metres, a couple of tables – but it feels like an ocean. She doesn’t recognise me now, so what if she never does? Her blank gaze flits across me dismissively and that’s it. I’m a nobody.

I should leave. Push my way through the door and follow the High Street back to my car. It was wrong to come here. I was wrong to come here.

When she glances up again, I’m too slow in turning away and there’s a moment in which it feels like we’re locked together. Something squeezes my stomach and there’s a second where I can’t breathe.

She looks at me and I look at her.

There is a strange electricity that we both feel, magnets being dragged together.

She pushes her glasses up from her nose so that they’re resting on top of her head. ‘Are you okay?’ she asks.

I stand and move around the tables, leaving my untouched tea until I’m standing in front of her. I’ve forgotten how to talk. Like those people in comas who wake up and suddenly know a foreign language but not their own. Even my thoughts are a crumpled, muddied mess, as if they’re in another language, too.

‘Are you Sarah Adams?’ I ask. I’ve surprised myself at being able to talk.

She squints and then lines are engraved into her forehead as she frowns slightly, trying to place me. I’m someone she met at a conference once, a daughter of someone she knows, some customer with whom she’s exchanged words before.

‘It’s Sarah Pitman now,’ she replies. ‘Do I know you?’

I want to say the name but the words are stuck – and then I don’t have to.

My mother’s eyes widen and she takes a huge gulp of breath. ‘Oh my God,’ she says, ‘It’s you. It’s really you.’

She blinks and there’s a moment where it feels as if everything has stopped. The infants at the back are no longer babbling, the waitress isn’t clinking cups into the dishwasher, the man walking past the café has frozen in the moment.

The space-time continuum itself has glitched.

Then she says it: ‘Olivia.’

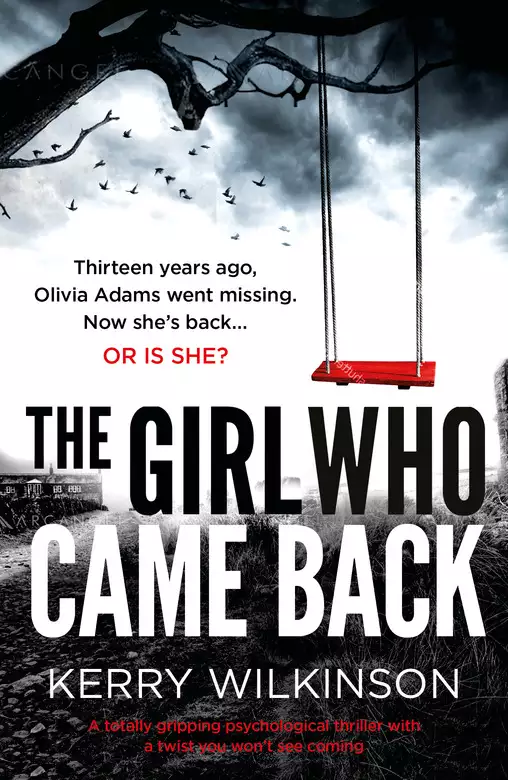

The hunt for a missing six-year-old Stoneridge girl has entered a third day as police focus on a stretch of woods on the outskirts of the village.

Olivia Adams was playing in the back garden of her family home when she disappeared a little after four o’clock on Saturday afternoon. The girl, who has long blonde hair, was wearing green shorts with a cream T-shirt featuring a cartoon of a fairy on the front. She was also sporting a red hairband.

Reports say the girl’s father, Daniel Adams, was watching the FA Cup Final inside the family home when his daughter disappeared.

Police are looking into reports of a suspicious car left outside the Adams home. A spokesman added that a 27-year-old man was helping them with their inquiries, although he insisted that there had been no breakthrough. The identity of the man is yet to be released.

Mother Sarah said: ‘We just want our daughter back. If anyone’s seen anything, however insignificant it may seem, please come forward. She’s a friendly child and is used to being around adults. She’s never run off and is often in the garden. We always keep the gate locked.’

The search for Olivia continued through the night on Saturday and all day Sunday, finishing at sunset. It was due to begin again this morning. The police have been aided by a large group of Stoneridge residents, who have helped comb through the Canvey Estate as well as fields that back onto the busy A622. The search has now moved further out of the village to centre on the western edge of Stoneridge Woods.

The disappearance of Olivia, a pupil at Stoneridge Primary School, has left the village in shock.

Georgina Hooper, a teaching assistant who has a daughter the same age as Olivia, said: ‘It’s devastating. This sort of thing doesn’t happen here. Everybody knows everyone else and it’s a proper little community. None of us can believe it. Olivia’s a lovely little girl and I hope she’s found soon.’

Despite the search party continuing largely uninterrupted for more than twenty-four hours, sources close to the investigation have admitted that authorities are baffled by a lack of clues.

‘It’s like she vanished into thin air,’ one observer noted.

Police have distributed maps of the immediate area and are focusing on a lane that runs along the back of the Adams home. More than a hundred officers have been brought in from neighbouring forces, with a helicopter deployed on Saturday evening to help with the search.

On the ground, however, morale appeared to be dimming. A woman who did not wish to be named said: ‘Everyone’s acting as if it’s already too late. One of the officers said the first three hours were critical but we’ve gone way beyond that.’

Ashley Pitman, who owns Pitmans Garage in the village, has been helping out with the search since the beginning and remains hopeful. ‘We’ll find her,’ he said. ‘We’ll keep searching for as long as it takes. Someone, somewhere must know something.’

A candlelit vigil and service to pray for her safe return is due to take place at Ridge Park at sunset this evening.

Police are asking for anyone with information to come forward.

Mum pushes up out of her seat. She’s a little shorter than me but only by an inch or so. She shuffles around the table, her gaze not leaving me for a moment, then she tugs at the longer parts of my fringe. It’s as if she’s making sure I’m real, not a ghost or a figment of her imagination.

‘I can’t believe it,’ she whispers.

She lets go of my hair but then cups my cheek with her hand. It’s warm and her touch is soft. When she realises what she’s doing, she apologises and hugs her arms across her front, like she’s trying to comfort herself.

‘You have the same eyes,’ she says, tears in her own. ‘All these years on and they haven’t changed.’

Of all the things I thought might happen, it wasn’t this. I had a speech planned about being back – and yet none of it has been necessary. She said the name and then she recognised my eyes. Now I’m here, and away from the, I’ll say this and she’ll say that, so I’ll reply with this, it’s obvious how silly all that was. I doubt I could’ve got even half a sentence out, let alone an entire speech.

‘I never stopped hoping,’ she says. Her voice is croaky, like that of a lifelong smoker.

I realise everyone’s watching and the silence I imagined is real. The waitress is holding a dirty cup in mid-air and the mothers have stopped gossiping among themselves. I don’t think they can hear anything that’s been said but the spark from across the room is too obvious to miss.

‘Where’ve you been?’ she asks. The number one question, of course. I have a speech for that, too.

‘Shall we go somewhere else?’ I reply. They’re the first words I’ve spoken since I asked her name.

It only takes a glance towards the back of the café for Mum to get the message. She stares at me for a moment more, blinks, and then launches into action. She snaps her MacBook lid shut and then fumbles with a bag that was underneath her seat. The laptop and papers are crammed inside and then she flusters her way back around the table.

‘I have to head out, Nattie,’ she says. The waitress still has the empty cup in her hand and it takes a moment for her to realise she’s being spoken to.

She jumps a little: ‘Oh, um…’

‘I’m on the mobile if you need anything.’

Nattie glances towards me and I wonder if she could hear us after all. She looks towards my table, where the tea sits untouched. She’s far too sensible to say anything even if she did overhear, so she smiles her waitress smile and says it’s not a problem.

The bell above the door jangles as we head out into what feels like a new world.

I have a mother and she has me.

It’s warm, the sun high and the sky blue. Stoneridge has a small High Street of a few dozen shops. There are hardly any chains; no McDonald’s or Starbucks, no tacky yellow arches or weird green and white mermaid thing. It’s all very Britain in Bloom; hanging baskets suspended from shop awnings and perfectly manicured strips of lawn dividing each side of the road. A summer of bunting and street fairs; bell-ringing on Sundays, with a packed house for the carol service every Christmas Eve.

We walk alongside each other and it’s as if we’re both too scared to say anything. Mum is a little shorter than I thought – she’s wearing low heels that clip-clop across the paving slabs. I’m in flats.

We pass an Italian restaurant that’s already open, with metal chairs and tables cluttering up the pavement. There’s one bank, then another; a hairdresser, at least three charity shops, a bakery and a WHSmith. There’s a pointy stone obelisk seemingly plonked at random at the end of the strip of grass, separating one side of the road from the other. It’s all very cosy and comfortable.

‘I don’t know where to begin,’ Mum says eventually. ‘I suppose… how did you know I was in the café?’

It’s not the question I expected.

I’ve almost forgotten. It was only this morning and yet everything’s a muddled mess in my head. ‘I went to the old house and—’

‘You went there?’

‘I didn’t know it was the old house. I thought you might still live there.’

Mum slows her pace by half a step. ‘Oh… of course. After your father and I divorced, we—’ She stops herself. ‘Sorry, there must’ve been a better way of telling you. Did you know we were separated?’

‘No.’

‘Oh…’ She stumbles over her words, starting to explain a couple of times but interrupting herself until she goes quiet again. ‘I have a new husband,’ she says. ‘His name’s Max. We moved to a new place on the other side of the village a couple of years after you, um…’

I wonder what word she’s thinking of. After I left? Disappeared?

‘Do you remember the old house?’ she asks.

She stops and glances sideways towards me and there’s the sense that she wants me to say yes but I can’t do that. Her eyes narrow and then open wider. She’s not sure what to make of me.

‘No,’ I reply. ‘I saw the name of the road online and it was easy enough to find. A woman opened the door and I asked for you. She said you’d moved out years ago. I thought that you’d moved away completely, another town or city, something like that – but she said you owned a café on the High Street and that you were sometimes there during the afternoons.’

‘That’s Janet,’ Mum says, starting to walk again. ‘She’s lived in the village all her life. She bought the house for the asking price when we put it up for sale. Did she recognise you?’

‘I don’t think so. That was this morning. I poked my head into the café then but you weren’t around, so I tried again at lunch, then again now. The waitress probably thought I was casing the joint.’

Mum laughs. ‘Nattie’s your age,’ she says. ‘You were in the same class at primary school. Used to play together during the holidays.’

‘Oh.’

We continue walking for a few steps. We’re past the obelisk and the end of the High Street. There’s a postbox on the corner and Mum goes in the opposite direction, heading towards a stone church with a towering steeple. The road has narrowed to barely a lane in either direction. There are small pebble-dashed houses on either side, but no pavement. Like a scene from a postcard.

‘Does the café name mean anything?’ I ask.

Mum stops again and so do I. She turns to face me, then places a hand on my shoulder. She squeezes. I’m flesh, blood and bone.

Real.

‘Of course it does,’ she replies. ‘Via’s is named after you. I always hoped this day would come.’ She gasps. ‘I never forgot.’

There are tears in her eyes which she blinks away before squeezing the top of her nose.

‘Do you want to go to the house?’ she asks. ‘The new one. We can talk there, perhaps? If that’s what you want…?’

‘That sounds good.’

She turns back towards the church at the end of the road. ‘The car’s parked over there.’

‘I can drive myself.’

‘Oh.’ She snorts in part-surprise, part-amusement. ‘Of course. You’re…’ she starts counting on her fingers.

‘Eighteen.’

‘Right. Eighteen and a half. You can drive, you can vote, get married. You can do anything now…’ She tails off and then adds: ‘Where are you parked?’

I point in the direction she indicated. ‘That way, near the post office.’

We start walking again and there’s a surreal moment as she makes small talk about how the council introduced free parking because the locals made a fuss about the old charge. Small-time politics and letters to the local paper. It all feels very normal, the type of thing that’s enormously important to a tiny number of people.

When she finishes the story, she laughs and then I join in. What else is there to do? This is village life. All that time away, all the unanswered questions, and we’re talking about free car parking.

We round the row of houses and follow a low drystone wall that rings the church until we’re in the car park at the back of the post office. There’s a big sign about how it’s closed on Thursdays and a sandwich board advertising discounted travel money.

Mum points to a black 4x4-cum-tank. Mine is the battered silver Fiat a few spaces along. She stops at the back of her vehicle and faces me once more. I’m a new puppy that needs to be smoothed and petted, to be hugged and loved. Everything’s there in her face. She offers a hand and then withdraws it, wary of letting me out of her sight in case I disappear once more.

‘I’ll follow you,’ I say, digging into my bag for the car keys.

She presses her weight from one leg to the other, still not ready for a goodbye, no matter how temporary. Like if she looks away, even for a moment, I might be gone again. She touches my arm, the gentlest of brushes with the back of her hand but it says more than her words.

‘Do you want to come with me instead?’ she asks, although it’s not really a question. It feels like a ‘no’ would devastate her. ‘It’s not far,’ she adds. ‘I can drop you back later if you want…?’

From nowhere, I’m a little girl again, strapped into the front seat of the car being chauffeured around. ‘That sounds good,’ I say.

It’s all stone walls, large detached houses, overgrown hedges and vast expanses of green as Mum drives out of the village. The road narrows, widens and then narrows again as she heads through the country lanes. She’s at least ten miles per hour under the speed limit, slowing steadily for all the corners, even though she must know when they’re coming.

After a few minutes of green, we reach another row of houses and I realise we’ve looped around the outskirts of the village. There’s a newish out-of-place estate of red bricks and cluttered on-road parking, then more hedges as the houses become further spaced apart.

Mum’s place has a large pebbled driveway that crunches under the wheels. There’s a large lawn at the front and the house itself is twice the size of the old one. It must have at least four bedrooms as well as the attached garage.

We’ve not spoken the entire trip but I’ve felt her looking sideways to me, perhaps wondering if anything about the village or journey has been familiar. Maybe it’s that she wants to check I haven’t gone anywhere, or that she hasn’t woken up from the dream.

She parks in front of the house, not bothering with the garage.

‘This is home,’ she says.

I follow her to the door and she fumbles with her bag, muttering about never being able to find her keys. ‘They’re in here somewhere,’ she insists, her fingers rifling through the various pockets before she eventually holds them aloft. ‘Damn things,’ she adds. Her hand is trembling as she unlocks the door.

Inside and we’re straight into an echoing hallway. There’s a view all the way through to the back garden, a tunnel of light beaming through the house, and I find myself drifting along the hall, into the kitchen until I’m staring out to the lawn beyond the window. It’s a little ragged, the grass creeping into the flower beds along the side, unmown for a week or three. There’s a tree at the furthest end, casting a thick shadow towards the house, and everything is enclosed by high hedges. There’s no gate, no way out other than through the back door.

Mum is at my side and she rests a hand on my lower back. She doesn’t say anything but she doesn’t have to. Her daughter and back gardens don’t mix.

‘This way,’ she says softly.

I follow her into another hall, along the wooden panelled floor and then into a conservatory. It’s a few degrees warmer than the rest of the house, offering another view of the back garden. There’s a bookshelf full of CDs and books, the spines faded by the sun. A skylight is open, allowing the vague thrum of chirping birds to creep inside. Mum sits on the washed-out sofa but I’m drawn to the bookcase, picking up the framed photograph from the top shelf.

Like everything else, it’s been bleached by the sun. The once green grass is a tea-stained brown, the blue sky is grey and murky – but the little girl in the centre is still clear enough. Her blonde pigtails are now a grainy sand colour, the green frog on her T-shirt a swampy brown. She’s smiling, holding up what looks like a plastic spade.

‘That was taken a month or two before everything happened,’ Mum says. She’s blinking rapidly, keeping any tears at bay. Trying to be strong. ‘Every time it was sunny, you’d want to be out in the garden.’

She sighs and takes a deep breath.

I have an urge to find a mirror, to compare the girl from the photo to the woman I am. The blonde hair must be similar but I wonder what else we have in common. I can’t believe my cheeks are as rounded as the girl with the frog T-shirt, but then a five- or six-year-old looks nothing like someone who’s eighteen.

After placing the picture back on the bookshelf, I turn and realise Mum is standing right next to me. She tugs the longer bits at the side of my fringe again and I let her. She has a faraway, vacant stare and it’s only when she blinks that it feels like she’s back in the room.

‘Sorry,’ she says, taking a step backwards. ‘I can’t believe it’s you… that you’re back. I know I said I kept on hoping but I’m not sure that’s true. Sometimes I hoped you’d be back but other times… I don’t know. People said I had to move on, to stop looking backwards, but it’s not as if you can turn it off.’

She bites her lip.

‘It’s all so… strange,’ Mum adds. She tails off and glances upwards momentarily. She gulps and then licks her lips. Her eyes are wet.

She isn’t wrong. I was close to chickening out in the café and there’s still a part of me that wishes I had. It would have been easier. I could’ve gone back to my other life.

In my mind, my mother was almost mythical or dream-like.

A mother. A mum.

Here, now she’s in front of me, she’s real. An actual person with emotions and expressions. The things I’d planned to say, the things I have to say, feel inadequate.

It isn’t only her. It’s me. I thought it would be easy, that I’d be strong, almost emotionless. But seeing this real person in front of me has changed that.

She sucks in her right cheek once more but not the left. This is what she does when she’s thinking.

She isn’t a mother any longer, she’s my mother.

‘If you don’t want to talk about things, that’s fine,’ Mum says. ‘We can sit here if you want…?’

‘We can talk.’

Her chest deflates as she lets out a long breath of relief.

‘Can we have something to drink first?’ I ask.

‘Of course.’

We move back through to the kitchen and then it’s more small talk about whether I wan. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved