- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

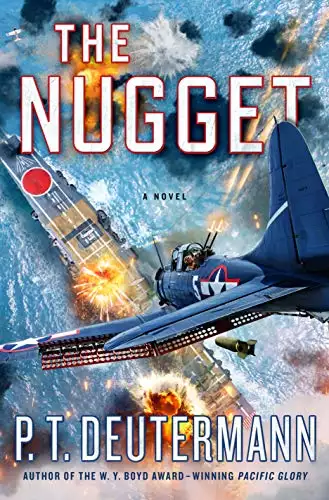

A novice naval aviator grows into a hero in this gripping and authentic WWII adventure by a master storyteller.

Lieutenant Bobby Steele, USN, is a fresh-faced and eager naval aviator: a "Nugget," who needs to learn the ropes and complex procedures of taking off and returning safely to his aircraft carrier. A blurry night of drinking lands him in an unfamiliar bed aboard the USS Oklahoma; later that day, the Japanese destroy Pearl Harbor. After cheating death and losing his friend in this act of war, the formerly naive Steele vows to avenge the attack.

Flying sea battle after battle, Steele survives the most dangerous air combat in World War II, including Midway, is shot down twice, rescued twice, and eventually leads a daring mission to free prisoners from a secluded Japanese POW camp. Packed with authentic military action on land and at sea in the Pacific Theatre of WWII and featuring a memorable protagonist based on a true-life hero, The Nugget is a first-class adventure by a former commander whose family served in the Pacific.

Release date: October 8, 2019

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Nugget

P.T. Deutermann

I awoke to the sounds of machinery. Ventilation fans, to be specific.

Where am I? I wondered.

I opened one eye and quickly clamped it shut. My mouth felt like it was filled with a wad of bitter cotton and I now knew how many brain cells I had because every one of them hurt. Maybe I should have used some of them last night. A tiny Greek chorus of some of the less badly dehydrated cells began a chant: You can not drink. You can not drink.

I took a deep, painful breath, still wondering: Where the hell am I?

There were other noises, now: a distant rumbling of some very large machinery, the clatter of a swab and bucket being used out in the passageway. Sound is vibration. My cells and I really didn’t need vibration just now. Like we’ve been saying since about 2200 last night, chirped the brain cells: you can not drink.

Then it came to me: passageway. I was on a ship. A very big ship. I opened that eye again and winced when I saw a bright white line stretched under the door to where I lay in bed. I sat up, carefully, and my stomach rewarded the effort with a lurch of nausea. And then I remembered the night before.

It had started innocently enough. Upon graduating from the Operational Training phase of flight training, I’d received orders to the USS Enterprise (CV-6), where I’d be assigned to the air group’s dive-bombing squadron. I debarked off the transport ship and slogged my seabag over to the base personnel office, where I got to hurry up and wait. Where’s my carrier? The Big E was at sea, somewhere, one of the clerks told me. Due back, well, sometime. I’d drawn myself up to my full height of five foot nine, okay, eight, inches and demanded more precise information. I am Ensign Robert Tennille Steele, United States naval aviator, and I need to know when and where I’m supposed to meet Enterprise.

The tired-looking personnelman was underwhelmed. You and about a hundred other guys, Ensign, he’d said. Here’s a voucher for the base BOQ. I suggest you go there now and get a room before they’re all gone. You’ll know your ship’s back in port when you see a big crowd headed down to the Ten-Ten dock. Join them. When you get there, look up. She’s a big gray bastard, you know? Uglier’n a stump, if you ask me, not beautiful like one of our battleships. Here’s your orders packet. When you do see the carrier, grab your seabag and your orders and report to the OOD on the officers’ brow, that’s at the back end, Ensign. Next.

I’d stomped out of there with as much dignity as I could salvage, which wasn’t much. The after brow. That’s at the back end. Wiseass. I’d been at sea for two years. I damned well knew which was forward and which was aft. This was the curse of having those lonely gold bars on your shirt collar: everybody assumed you knew absolutely nothing, even though I was an academy graduate, had completed two years at sea in a cruiser, and after that, just over a year at Pensacola and other flight-training fields. In the Army they called their second lieutenants shavetails, whatever that meant. In the Navy all it took was for someone to say the word “ensign” and you were immediately lower than whale dung. It was almost like being a plebe again. It reminded me of what one of the chiefs had said when I reported aboard my cruiser: the three most dangerous things in the Navy are a boatswain mate with brains, a yeoman with muscle, and an ensign with a pencil.

That evening I’d gone to the O-club to get a beer but mostly to sulk. Just before leaving San Diego at the close of advanced flight training my girlfriend back in Omaha sent me a Dear John letter. She’d understood that, as a brand-new naval officer, I wouldn’t see much of Omaha, or her, once I graduated from Annapolis. Added to that problem was the Navy’s rule that new ensigns could not marry for two years after commissioning. My application for flight training at the end of those two years was apparently the final straw. We broke off our unstated engagement, promising to remain friends and maybe try again once I completed my Navy obligation. I got more mail from my folks back in Omaha than I did from her, and the Dear Bobby wasn’t much of a surprise. I still felt like sulking.

I’d of course asked around the O-club bar if anyone knew when the Big E was coming back in. That got me several suspicious looks and headshakes, even though I was in uniform. The bartender pulled me aside and explained that the movements of important ships like the Enterprise were secret, especially with all this war talk going around. In other words, stop asking or some people in suits will show up and take your ignorant ass away in irons.

I guess I should have known that. He’d been friendly enough about it, but that was probably because I was an ensign and he felt sorry for me. He’d even topped up my beer for free when he saw how crestfallen I’d looked. Then Ensign Mick McCarthy, one of my classmates, showed up. It seems he was stationed on the battleship USS Oklahoma as 3rd Division officer. He immediately ordered me a second beer and we got caught up. Long story short, before I knew it I was pee-lastered. Mick, being Irish, was of course just getting up a head of steam. The last thing I remember about the club was that Mick ordered me a Me Tie, or something like that. Mick called it dessert. The bartender cut me off after one after I dropped the empty glass.

How or why we ended up on the battleship Oklahoma remained an annoying mystery, right up there with getting in consecutive breaths of air without hurting my lungs, or, worse, having that other eye open suddenly. Apparently the first eye had spilled the beans on how much pain that slim band of white light could inflict.

I can not drink. I must never drink.

At that moment, the ship’s announcing system switched on with a snap and a crackle. Then the Antichrist started blowing a bugle. An amplified bugle, no less, telling us that reveille was upon us. I covered my face and ears with a pillow against the hateful noise, which finally, mercifully, stopped. To be replaced with the braying of a boatswain mate who wasn’t aware there was an amplifier present. Apparently it was time for sweepers to start their brooms and give the ship a clean sweep-down, fore and aft. That was followed by detailed instructions as to where to sweep (all interior decks, ladders, and passageways) and how to sweep again: give the ship a clean sweep-down, fore and aft, with every raspy syllable drilling into my poor head. During the next thirty minutes I stumbled down to the officers’ head where I embarrassed myself, and then I slunk back to the stateroom, got my uniform back on, and then my shoes—socks were hard, shoes a bit easier.

I collapsed back into the desk chair. I needed the chair to properly hold my aching head in both hands, eyes closed again, while the entire ship was treated to even more amazing announcements: mess gear; breakfast for the crew; all hands to quarters, officers’ call, and all this on a Sunday when any civilized aviation outfit would simply have piped holiday routine and been done with it. The final insult came when some evil bastard blew a police whistle over the announcing system, meaning: attention to morning colors. I did see colors, but not of the national kind. Gawd, I was hung over.

Then a surprise. Instead of actually saying, Attention to colors, the bosun said: What?

I echoed him. What?

The bosun was still holding down the switch on his 1MC microphone when somebody near him up on the bridge yelled: Hit the deck! loud enough to make me roll out my desk chair and hit the deck. At which point said deck, that solid battleship steel deck, punched my whole body so hard it knocked the wind out of me, followed a tenth of a second later by a truly thunderous roar from somewhere way down in the guts of the ship. I felt her roll ten degrees to port and then back over to starboard, where, even scarier, she stayed. The stateroom’s built-in desk and bureau set had been dislodged by the blast and was leaning out of the bulkhead and wedged on the desk chair right over my head. I tried to disentangle myself when all the lights flickered out. Then we got hit again, somewhere farther aft. Same gut-punching, knee-banging booming explosion, followed quickly by what sounded like the ship’s antiaircraft guns beginning to hammer away topside.

Suddenly I got myself clear of the chair and the trash can. As I tried to scramble to my feet I realized I was wrong about that: the chair and the trash can had gotten clear of me, rolling across the stateroom deck all by themselves, along with all the other loose gear. The ship was now listing by at least fifteen degrees, maybe even more. My hangover evaporated, extinguished by adrenaline.

Gotta get out of here, I thought. Then came a third hit, this one definitely underwater, the sound muffled but the impact no less mortal. I could literally hear and see the bulkheads and the door frame deform under the impact. I crawled to my feet, felt for the stateroom door, and tried to get it open. No dice: it was wedged shut. I kicked and pulled at it in the darkness until it gave way, wrenched it open, and saw light: battle lanterns were glimmering all along the passageway, their smoky yellow beams revealing at least a foot of water rushing down the passageway.

Water. Running down the passageway? No. No. No!

The deck was now tilting over even more, piling that water up against the outboard bulkhead as I scrambled down the passageway toward a watertight hatch visible about 40 feet aft. Where was everybody? The main steel girders of the ship were groaning now, accompanied by a thousand cracking and pinging noises as rivets were pushed out of the metal like cold bullets. There were no more guns banging topside but still lots of explosions, some close, some distant now, as if our unseen attackers had tired of Oklahoma, and little wonder. I finally reached the watertight door which someone had dogged down, but only partially. By then I was almost walking on the bulkhead as the ship’s list had increased to over thirty degrees. Despite the warm harbor water swirling past my knees, I felt a cold chill: the Oklahoma was going to capsize. She was going to turn turtle and go completely upside down.

I grabbed the hatch-operating handle and twisted it upwards as hard as I could. I couldn’t budge the damned thing. The water was piling up on my side of the hatch and for the first time I thought I was going to drown here. I hit that operating handle again but with no better results. I saw a fire extinguisher mounted on the dry-side bulkhead. I grabbed it and used it as a hammer, striking upwards on the handle. I thought I could hear panicked shouting in the next compartment. Then the top of the extinguisher snapped off and the stink of acid foam filled the flooding passageway. I recoiled from the acrid cloud, tripped, and went underwater for a moment. I bobbed back up, eyes stinging, fighting a rising panic.

Suddenly the handle moved, and then swung all the way up. The hatch popped open, knocking me once again back into the passageway. Somebody grabbed my shirt and hauled me through the hatch into a companionway, the place where a double ladder from the next deck up reached down to the deck I was on. The two ladders were covered in dungaree-clad sailors, some only partially clad, all trying to fit through the two hatches up above at the same time. My rescuer dropped me into two feet of water on the dangerously sloping deck. I was about to say something when a blast of boiler steam began roaring up the stack, which must have been right behind the companionway. The noise drowned out all the shouting around the ladder. The crowd streaming up the ladder thinned out, as if encouraged by that tremendous roar of escaping high-pressure steam.

One of the last men on the ladder saw me just sitting there. He yelled something at me, but all I could hear was the thunder of escaping main steam. He gestured at me with both hands: C’mon, Ensign. C’mon. Then he was gone, disappearing up the ladder into a sudden waterfall that began to come back down the ladder.

That finally registered.

I bolted for the empty ladder and went up like a striped-assed ape, taking every third rung, steel treads skinning my shins as if to say: Faster, faster! She’s going. And she was going. She was beginning that final ponderous roll. I caught a slim glimpse of daylight over on the high side and lunged for it even as a huge cascade of water came through a main deck hatch. I don’t know how I got through that but I did. I slid down the hull, bumped off the armor belt, and dropped into the harbor, joining a swarm of men who were frantically trying to get away from the capsizing giant.

Why get away? Weren’t we safe now? Then I remembered: if she went all the way down, sank out of sight, she’d suck anybody in the water nearby down with her. I struck out in the away direction, vaguely aware that there were fires everywhere along battleship row accompanied by the drone of unfamiliar aircraft engines. A titanic explosion erupted somewhere down the Ford Island waterfront, closer to the inner harbor. It was so big it punched my eardrums. By then most of us realized we weren’t getting anywhere as Oklahoma’s massive 26,000-ton hull displaced an equal amount of harbor water when she capsized. All of that water was now flowing back towards the upside-down ship. It swept us up onto the barnacle-covered hull and then dragged us back down in a succession of waves. On the next surge those who could tried to scramble up the hull itself, grabbing rivet heads, ridges of armor plate, and even protruding barnacles, which were sharp as knives. I was so frightened that I don’t remember clambering all the way to the keel but I did, my bare hands stinging from a thousand cuts. Somewhere back aft a mighty geyser of air and water was shooting a hundred feet into the air from one of the torpedo holes as the ship flooded. There’d been about thirty of us who’d gotten out, but I was the only one who’d made it to the keel.

Exhausted, I lay spread-eagled along a section of the ship’s keel and tried to regain my wits. I now knew what people experienced during a large earthquake: when the earth itself moves, your brain can’t process it. It was terrifying. Then I smelled fuel oil, lots of it, followed by a hot gust of flame as the oil ignited back down by what had been the waterline. Instinctively, I started crawling backwards to get away from those grasping flames and worse, the choking clouds of oily black smoke that threatened to displace all the breathable air. Then I heard the broken screams of those still down in the water as the flames reached them, driving them underwater and then, inevitably, back up, lungs bursting, to the surface, there to inhale superheated air, flame, and smoke.

I wish I could say that I bravely held my ground or tried to rescue some of them, but the truth was I simply pressed my face down onto the battleship’s keel, squeezed my eyes shut in sheer terror, and tried to ignore the continuous sounds of explosions nearby, the chatter of machine guns as the Japs came back on strafing runs, and the screams of the men down in the water, which one by one subsided into a sickening silence. At some point my brain had had enough. Everything went mercifully black.

TWO

Someone was lifting me into an upright position and then patting my face, none too gently.

“Sir? Sir? You wounded?”

I opened my aching eyes. Two grimy sailors in wet, oil-soaked dungarees had ahold of me. I blinked several times and then looked over their shoulders at the spectacle of the entire Pacific Battle Fleet either aflame, upside down, or barely afloat.

“What the hell happened?” I croaked.

One of the sailors, a petty officer third class, stared at me with frightened eyes. “The goddamned Japs, that’s what happened,” he said. “Now: we gotta go. Are you injured?”

“No, I don’t think so. Except for my hands,” I said. I looked around at the mountain of steel on which I was sitting. “I was inside. Jesus!”

“Okay, sir?” the petty officer said. “C’mon, we gotta get you down into the P-boat. Then we gotta get over to mainside. We got lotsa casualties in the boat. You ready?”

I blinked a couple of times. Ready? Ready for what? Then the pair of sailors took me by the shoulders and we all three slid down the hull of the overturned battleship to the personnel boat that was waiting for us. Barnacles ripped my khaki trousers and the backs of my legs. The personnel boat was grossly overloaded, its gunwales only inches from the oily water. Inside lay about thirty casualties in various states of crisis. A chief petty officer was standing at the conning console. He pulled a lanyard once, sounding one bell, and the boat surged up against the steel hull long enough for the two sailors to pull me into the back of the boat. Somewhere behind us, out of sight because of the steel mountain which had been Oklahoma, something blew up with a hard, ear-compressing blast. Moments later large things began to pepper the water around us. The chief pulled the boat away from the hulk of the Oklahoma and turned it towards the other side of the harbor. He looked over his shoulder at me.

“You injured, Ensign?” he asked, his voice betraying carefully restrained fear as he struggled to maintain some form of command composure.

“No,” I replied. “I was—”

He cut me off. “You’re an officer. You know first aid. How’s about going forward and helping with the wounded?”

“Certainly,” I replied and then crawled into the passenger compartment just forward of the coxswain’s console as the chief carefully turned the boat and headed for the Ten-Ten dock across from Ford Island. Two white-hats were trying to tend to the wounded with the P-boat’s tiny first-aid kit. I was shocked by the carnage: men whose every inch of visible skin was roasted black and weeping serum as they tried to breathe into seared lungs. One man right in front of me was holding up his right arm which ended just above his wrist in a bloody tourniquet composed of a broken mop handle and the sleeve from someone’s shirt. The man’s eyes were closed as he cursed the Japanese through clenched teeth. The man next to him had a gaping chest wound and was obviously dead. Another blast from the direction of Ford Island made everyone cringe, but we kept at our clearly hopeless task, trying to stop bleeding and help burn victims breathe. I joined in their frantic efforts even as I realized we weren’t going to be able to do much more than try. For a few seconds I had to close my eyes and take a deep breath. Then I shook it off and jumped back in to help.

Ford Island across the harbor had disappeared behind towering clouds of black smoke by the time we reached the shipyard. Two destroyers that had been in dry dock just forward of one of the battleships were blackened wrecks. There were dozens of ambulances, utility trucks, and even private vehicles swarming around the base of the pier. Another P-boat was unloading wounded ahead of us, so the chief throttled back and waited. Soon there were two more boats behind us, and more coming out from under the smoke cloud covering the harbor. When we finally nudged our way to the landing, a gray-faced nurse met us and did a quick, visual triage. She noticed me as I was holding up a sailor whose back was probably broken.

“You injured, Ensign?” she called down to the boat, staring at the blood all over my khaki uniform.

I shook my head. I’d tried to answer her but my mouth was too dry.

“Okay,” she said. “You can help me. Everybody’s going to the triage station, right over there. The docs decide who’s going to the hospital, and who isn’t. Any more able-bodied in this boat?”

Four sets of bloody hands rose.

“Organize it, Ensign,” she told me and strode back to the main triage station.

I did. As soon as all the passengers had been lifted by hospitalmen to the pier and onto stretchers, the chief backed the P-boat away from the landing and headed back out into the harbor. I saw to it that the stretcher cases were attended to, and that the dead were moved away from the survivors. I could hear sirens going all over the shipyard. There were many fires blazing on this side of the harbor as well. The first thing every wounded man wanted was water, which was in short supply in the noisy chaos around me. I, myself, was desperately thirsty. Then one of the base fire trucks showed up, covered in soot and with bullet holes in the cab doors. Three firemen got out and rigged a 2.5-inch hose down to the triage station. One of the firemen cracked open the nozzle, allowing all the triage medical personnel to wash their hands and faces for the first time. The cries for water from the dozens of stretcher cases became louder.

I noticed a trash skip nearby that had a case of empty Coke bottles in it. I gathered up six of them, got in line for the nozzle, rinsed them out, and then filled all six. I went back to the ever-growing triage line and began offering sips of water to as many of the wounded as possible. I’d gone through five of the six bottles when a nurse yelled at me to knock it off, pointing out that the water could kill patients with abdominal wounds. There was an audible groan from the crowd of wounded, but I did as I was told. Ensigns did not argue with Navy nurses.

I drank the last bottle myself and then sat down on one of the bollards lining the big Ten-Ten dry dock. Across the shattered harbor there were huge oil fires and even bigger clouds of intensely black smoke flickering with boiling red flames. The tops of some of the stricken battleships would be visible for a few moments before being enveloped again, swallowed up by their own funeral pyres. I looked for the Oklahoma but was unable to make her out, only then remembering she’d capsized. There was now an even longer line of boats waiting at the landing. The air along the waterfront stank of burnt oil and blood.

I decided to get out of there. I’d survived. I’d helped, as best I could, and I’d been yelled at anyway. Now it was time to find my seabag and the Big E.

Copyright © 2019 by P. T. Deutermann

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...