- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

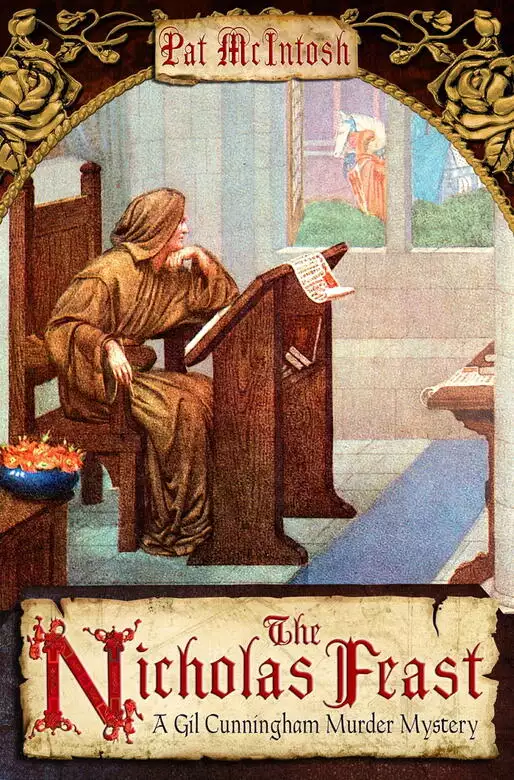

Synopsis

Glasgow 1492. Gil Cunningham remarked later that if he had known he would find a corpse in the university coalhouse, he would never have gone to the Arts Faculty feast. In this mysterious adventure Gil Cunningham returns to his old university for the Nicholas Feast, where he and his colleagues are entertained by a play presented by some of the students. One of the actors, William Irvine, is later found murdered and Gil assisted by Alys, begins to disentangle a complex web of espionage and blackmail involving William's tutors and fellow students. Matters are further complicated by the arrival of Gil's formidable mother who is determined to inspect his betrothed. Little do Alys and Gil realise that it will be she who provides the final, vital key to unmask the murderer and lay his motives clear.

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 276

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Nicholas Feast

Pat McIntosh

‘But then,’ said Alys his betrothed, considering this seriously, ‘you would never have met Socrates.’

The day began well enough. In the bright sunshine after early rain Gil, his academic robes in a bundle under his arm, had strolled down the High Street past the University,

where several people in gowns and furred hoods were already exchanging formal bows with a lanky red-haired student before the great wooden door. Further down the street, in the rambling stone-built

house called the White Castle, he found Alys and her father the French master mason, just breaking their fast with the rest of their household after hearing the first Mass at Greyfriars.

‘Gil!’ said Alys in delight, and sprang up to kiss him in greeting.

‘Bonjour, Gilbert,’ said Maistre Pierre cheerfully, his teeth white in his neat black beard. He rose broadshouldered and imposing from his great chair and waved at an empty

stool. ‘Have you eaten? What do you this early on a Sunday morning?’

‘The Nicholas Feast,’ Gil reminded him. He smiled at Alys, still standing slender and elegant beside him in the brown linen dress that matched her eyes. Like most unmarried girls in

Scotland she went bare-headed, and her honey-coloured hair fell over her shoulders. He savoured the sight for a moment, thinking again how fortunate he was, that this clever, competent, beautiful

girl was to be his wife, then tipped her face up with a gentle finger and kissed the high narrow bridge of her nose. ‘I hoped Alys would help me robe,’ he continued. ‘The

procession will start from the college, and if I must walk there alone in these ridiculous garments I had rather do it from here, four doors away, than from Rottenrow. At least when we ride up to

St Thomas’s I’ll be in company with the whole of the Arts Faculty.’

‘They are not ridiculous garments!’ Alys said indignantly. ‘They are the insignia of your learning! Come and sit down, Gil.’

‘Why is it called the Nicholas Feast?’ asked Maistre Pierre, ladling more porridge into his wooden porringer. ‘St Nicholas’ day is in December. This is May.’

‘The Feast of the Translation of St Nicholas was last Tuesday,’ Gil said. He bowed to Alys’s aged, aristocratic nurse, and nodded to the rest of the household, who were

ignoring the French talk at the head of the table. Setting the bundle of his robes on the floor he sat down and accepted a bannock from the platter Alys passed him. ‘When he was translated to

Bari, I suppose, though where from I don’t recall. And this is the first Sunday after. The man who founded our feast left exact directions. We’re to ride in procession to hear Mass at

eight of the clock in St Thomas Martyr’s, out beyond the Stablegreen Port, and come back down through the town with green branches, and then we have a meeting, and then we have the

feast.’

‘He left money for the feast, too, I hope?’ said Maistre Pierre.

Gil nodded, spreading honey on his bannock.

‘There is some, but we are all expected to pay up as well. Eighteen pence it has cost me.’ The mason pulled a face. ‘It would be double that if I had a benefice.’

‘I had hoped,’ said Alys with diffidence, ‘we could write to your mother today. Her letter needs an answer, you must agree.’

‘Oh, aye, I agree,’ Gil said ruefully. ‘But not today. I am committed to the feast. Perhaps tomorrow.’

When grace had been said, the dishes had been carried out and the great board lifted from its trestles, Alys’s nurse Catherine rose stiffly and said to the mason, ‘I leave your

daughter in your charge, maistre.’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Maistre Pierre. ‘And the baby is with Nancy. Go and see to the boy, if you will, madame.’

She curtsied with arthritic elegance, said, ‘Bonjour, maistre le notaire,’ to Gil as she passed him, and stumped out of the hall among the hurrying maidservants. Alys unfolded

Gil’s robes.

‘Your mother’s letter,’ she said again, shaking out the cassock. ‘Is it – is that really what she thinks?’

‘She’ll come round to it,’ Gil said. ‘Remember, my uncle is in favour.’

‘But if your nearest kin can’t agree about your marriage –’

‘Perhaps when my uncle can spare me, I should go out to Carluke,’ he suggested.

‘Yes!’ She smiled up at him. ‘If you can discuss it with her, I’m sure you will coax her round.’

‘Tell her how Alys will be dowered,’ said Alys’s father robustly. ‘That will persuade her.’

‘It’s possible,’ said Gil, concealing his doubts. He pulled off his short gown and began to unlace his doublet. ‘Meantime I need help with these ridiculous

garments.’

‘They are not ridiculous!’ she said again. ‘Which way round does this go?’

Maistre Pierre watched in mounting astonishment as Gil was arrayed in the black cassock and cope (‘At least this one has two slits for my hands. Some only have one.’), the furred

shoulder-cape, the blue fur-lined hood, proper to a Master of Arts of the University of Glasgow.

‘All of these garments are wool,’ he observed. ‘You will be warm. And what is that scarf thing? At least that is silk, though it is furred as well.’

‘Oh, father,’ said Alys. ‘You remember the men of law wearing those in Paris, surely? It goes on his shoulder. It’s a pity it’s red when your hood is blue,’

she added. ‘Does it need a pin, perhaps?’

‘This is the first time I have worn it all complete,’ said Gil, craning over his shoulder at the hood. ‘I must look like a Yule papingo,’ he added in Scots.

‘A parrot?’ said Maistre Pierre, grinning.

‘No, no, it looks magnificent,’ Alys declared.

‘At least I won’t be alone. The entire procession will be in formal dress.’

‘And you are to ride in those long skirts?’ continued the mason, as Alys shook the moth-herbs out of the white rabbit-skin lining and stood on tiptoe to pin the red chaperon

on to the layer of fur already on Gil’s shoulder. ‘Where is your horse?’

‘My uncle sent down to the college earlier with half a dozen beasts loaned from the Chanonry I’ll have the use of one of those.’ Gil settled his felt hat on his head, then took

Alys’s hands in his and kissed them. ‘I must go. Tomorrow we’ll write to my mother, sweetheart,’ he promised her.

‘Which reminds me indirectly,’ said Maistre Pierre. He got to his feet. ‘I see you to the street. Our neighbour is expected in town.’

‘What, Hugh Montgomery?’ Gil turned to stare. ‘What brings him to Glasgow? The King’s at Stirling, by what my uncle says, and the rest of the Court with him.’

‘Catherine thought it might be to do with the college,’ said Alys.

‘How does Catherine learn these things?’ Gil wondered. ‘She speaks no Scots.’

‘Your pardon, maisters, mistress,’ said an anxious voice from the kitchen stairway.

They all three turned. In the door at the head of the stairs stood a stout, comely woman dressed in respectable homespun. As they looked she bobbed a nervous curtsy and came forward.

‘Your pardon for interrupting,’ she said again, ‘but they’re saying in the kitchen you’re for the college the day, maister? Is that right?’

‘This is Mistress Irvine, Gil,’ said Alys. ‘A kinswoman of Kittock’s –’

‘Aye,’ agreed Mistress Irvine, nodding and beaming. ‘My good-sister’s good-sister, that’s who Kittock is, and a good friend to me and all.’

‘– and Davie’s aunt,’ continued Alys. ‘She has come from Paisley to see him.’

‘How is the boy today?’ Gil asked, with sympathy.

‘He’s still sleeping the maist o’ the time,’ said Mistress Irvine, looking troubled. ‘And he minds nothing even when he’s awake. I think it was you that found

him, maister? Blessings on ye for that, sir, and his mother’s and all.’

‘He improves slowly,’ said the mason.

‘It’s only two weeks, father,’ said Alys. ‘It takes longer than that for a broken skull to mend. Mistress Irvine was very distressed to see her nephew in such a state,

Gil, the more so as her foster-son at the college is strong and healthy.’

‘The contrast must be painful,’ Gil commented wryly. The mason’s injured mortar-laddie was a reminder of an episode which he would have wished to forget, had it not resulted in

his betrothal to Alys. ‘Has the other boy visited Davie? The company would be good for him.’

‘Och, no. William’s ower busy at his studies,’ explained Mistress Irvine, and bobbed another curtsy. ‘I wonder if I might trouble ye, sir? It’s just to leave this

paper for him with the man at the yett. It’s for William Irvine.’ She produced a folded and sealed package.

‘That’s no trouble.’ Gil put his hand out. A line of verse popped into his head: Little Sir William, are you within? Which of the ballads was that?

‘Only he said he’d be busy today, he can’t come to see me, and I don’t like to go back, the porter was as awkward yesterday about sending to fetch him to the yett, and if

they’re all taigled with this feast I’d only be in the way. It’s a shame I never took it with me when I went out to Vespers.’

So the guardian of the college’s great wooden door must be the same fellow Gil remembered from his own time. ‘It’s no trouble,’ he said again.

She put the little package into his hand and curtsied again. ‘Blessings on ye, sir. Oh, here, you’ve lost your wee scarf.’ She stooped to lift the swatch of silk and fur.

‘You’ll not need that round your neck the day, maister, it’ll be warm enough when it’s no raining. And I’ll away back down to the kitchen, mistress, and see to that

remedy I promised Nancy for the bairn. We’ll see if we can’t get him taking more than milk with honey and usquebae, won’t we no?’

‘We will be aye grateful if you do, mistress,’ said Alys. ‘I believe he has eaten only by accident since his mother died.’ She watched Mistress Irvine puffing her way

down the kitchen stair, then turned to fasten the scarf back on Gil’s shoulder. ‘There, I have used two pins this time. Take care,’ she said earnestly. ‘Of the Montgomerys,

I mean.’

‘Yes indeed.’ The mason made for the door. ‘Maybe you do not go about alone for a while. Bah! It is raining again.’

‘The Montgomerys have killed no Cunninghams for at least six months,’ Gil said. ‘That I know of,’ he added.

He hugged Alys, and bent to kiss her. For a long moment she returned his embrace, with the eager innocence which he found so enchanting; then she drew away, suddenly shy, and he dropped another

quick kiss on the bridge of her nose, and followed Maistre Pierre down the fore-stair and across the courtyard in the rain.

Pacing up the High Street with the dignity imposed by the heavy garments, Gil glanced at the tall stone house belonging to Hugh, Lord Montgomery and wondered again what that turbulent baron

wanted in Glasgow. Montgomery had no Lanarkshire holdings and no need to keep on the good side of the Archbishop, unlike Gil’s own kindred, and the holdings and privileges in Ayrshire which

were the cause of Montgomery’s bloody dispute with the Cunninghams were all administered from Irvine. Perhaps, Gil speculated, Alys’s governess was right and the family wished to make

its mark on the college in some way.

The High Street was now completely blocked outside the college gateway by the mounts waiting for the procession. John Shaw the Steward was welcoming another arrival. Gil avoided the heels of a

restless mule and picked his way to the door. Here he was met by the same student he had seen earlier, a gangling youth with a faded gown and a fashionable haircut, who bowed deeply, flourishing

his hat so that raindrops flew from it.

‘Salve, Magister. The college greets you. May I know your name?’

‘Maister Gilbert Cunningham,’ said Gil, ‘determined in ’84.’

The student straightened abruptly, clapping the hat back on his head.

‘Gang within, maister, if ye will,’ he said, cutting across Gil’s greeting to the college. ‘The Faculty’s in the Fore Hall.’ He waved a long arm towards the

great wooden yett and the vaulted passage beyond it, and turned away.

A little startled by this incivility, Gil made his way into the passage, pausing at the porter’s door. As he had surmised, the occupant of the rancid, cluttered little room was the same

man he remembered from his own days at the college, a surly individual with a bald head and a flabby paunch.

‘Good morning, Jaikie,’ he said politely. ‘I see you’re still in charge here.’

‘Oh, it’s you, Gil Cunningham,’ said Jaikie, looking him up and down. ‘I thought ye’d be here earlier, but maybe since ye’re to be married, ye’re done

with early rising.’ He produced an unpleasantly suggestive leer. ‘And I hear there’s a bairn already?’

‘There is,’ agreed Gil, ever more politely. ‘A motherless bairn being fostered by the household.’

‘Aye, right. And what do you want?’ demanded Jaikie. ‘I’ve enough to see to, dealing with this feast, without idle conversation round my door.’

‘I have a package here for William Irvine.’

The man’s expression flickered.

‘Ye have, have ye? Let’s see. From Billy Dog, is it?’

Gil handed over the folded paper. Jaikie turned it in his hands, flicked at the seal with a dirty thumbnail, and grunted.

‘It’s no from Billy Dog. Well, ye can deliver it yirsel. That’s William Irvine out there at the yett, capering like a May hobby, welcoming the maisters.’

‘The boy with the red hair?’

‘Aye, the same.’ Jaikie cast a glance out of his window at the crowd in the street. ‘Ye’ll need to be quick. They’ll mount up soon.’

Gil went back out to the doorway and waited while the rain stopped, the sun came out, and the red-haired boy greeted another pair of graduates with flowery compliments about the college’s

sons. One of them produced a stock phrase in reply, about the fountain of wisdom; the other grunted, ‘Aye, thanks,’ and pushed past Gil into the tunnel.

‘William,’ said Gil. The boy turned, and recognizing Gil raised his hat briefly and attempted to look down his nose at him. Tall though he was, Gil topped him by several inches, so

he was unsuccessful in this, but he assumed an expression of vague contempt.

‘I have a package for you from Mistress Irvine, William,’ said Gil politely, holding it out. Little Sir William, are you within? he thought again.

‘From –? Oh,’ said William, taking it. He turned the little bundle over, reading the clumsy writing on the cover. ‘Thank you,’ he added, as if the words tasted

unpleasant, and then, almost warily, ‘Did she say anything about it?’

‘Not a thing,’ said Gil. ‘You’ll need to open it to find out.’

‘Well, it’s what one usually does with a letter,’ said William, with casual impertinence. Gil raised one eyebrow, and the boy looked down and turned away. ‘Thank you,

maister,’ he said again, ostentatiously studying the writing on the package.

Gil made his way through the tunnel into the Outer Close where he paused, savouring the scene. The place had scarcely changed in the eight years since he had left; the thatch was sagging, the

shutters were crooked, even the weeds between the flagstones seemed the same. Now, where had that ill-schooled boy said? Yes, in the Fore Hall.

One or two Faculty members were about in the court, but judging by the noise most were above in the hall. As Gil turned towards the foot of the stair, William hurried across the court, in too

much haste even to lift his hat to a passing Doctor of Laws. He appeared to be making for a tower doorway in the south range, but before he reached it a man in the robes of a Dominican friar

emerged from the tunnel which led to the Inner Close. William, catching sight of him, checked and turned to intercept him.

‘Father Bernard,’ he said clearly. ‘I have something here that will interest you.’

As Gil reached the top of the stair he settled on a word for William’s expression: gleeful.

In the outermost hall of the college building a roar of polite Latin conversation rose from the assembled Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow, thirty or forty men in woollen copes like

Gil’s or the silk gowns of the Masters of foreign universities circulating in an aroma of cedar-wood and moth-herbs. Gil paused in the doorway to look over the crowded heads and decided

against making his way to his proper station, among the other non-regent Masters, the graduates of the University who did not hold teaching positions. If he waited here, he could slip into his

place as the procession left.

He could recognize many of the company. Yonder was John Doby, small, gentle and balding. He was the Principal Regent in Arts, in charge of teaching and all matters of the curriculum, and had

taught Gil Aristotle thoroughly and exactly. Beside him, tall and silvertonsured, Patrick Elphinstone the Dean, whom Gil remembered as a conscientious and alarming teacher. There was David Gray the

Scribe, a poor teacher and an ineffectual man, with the red furred hood of a man of law rolled down on his shoulders and straggling grey hair showing round his felt cap.

The procession was forming up. Gil stood aside from the door, and the Dean and the Principal passed him in their high-collared black silk gowns and long-tailed black hoods, each with the red

chaperon of a Cologne doctor trailing from his left shoulder. As they reached the doorway the light changed, and the May sunshine gave way to another vicious May shower.

‘Confound it!’ said Dean Elphinstone, stopping abruptly. ‘The hoods will be ruined! Principal, why did you insist on the silk hoods? Fur at least would dry out.’

‘It’s summer, Dean.’ Maister Doby peered past his taller colleague. ‘A wee bittie rain’ll not hurt you.’

Gil looked over their heads at the large drops bouncing off the paving stones of the Outer Close and remarked, ‘Now if only we were allowed to wear plaids with our gowns . . .’

Both men turned to look at him. Behind him the cry of ‘It’s raining!’ had run round the hall, in Scots and Latin, and some jostling began as people dragged silk-lined hoods and

rich gowns over their heads in the crowd.

‘Ah, Gilbert,’ said the Principal, switching to the scholarly tongue. ‘It is good to see you. Do you remember David Cunningham’s nephew, Dean, who was one of our better

determinants in – let me see – ’84, wasn’t it? And then –’

‘Paris, sir,’ Gil supplied. ‘Law. Licentiate in Canon Law.’

‘Oh, aye. And now trained as a notary with your uncle, I believe?’ Gil nodded, and bent a knee briefly in response to the Dean’s inclined biretta. Someone complained as his

elbow met a ribcage, and he threw a word of apology over his shoulder. The Dean was speaking to him.

‘Are you the man about to be married?’

‘I am,’ agreed Gil, bracing himself for the usual congratulatory remarks. At least this is an educated man, he thought. Not like Jaikie.

‘Hmf. It seems a pity to waste your education,’ the Dean pronounced. ‘Why marry her? Why not take a mistress, if you must, and pursue the church career?’

Gil swallowed his astonishment.

‘My uncle thought otherwise,’ he said, taking refuge in politeness again.

‘Hmf,’ repeated the Dean, and surveyed him with an ice-blue stare. ‘You have never undertaken the required course of lectures, Gilbert?’

‘What, since I left here? No, sir. The opportunity has not presented itself.’

‘Would you come to see me about that? We cannot get regents from outwith the college, and if you were to carry out your duty in delivering such a course it would benefit both the bachelors

and yourself, since the bachelors could add another book to their list, and by it your degree would be completed and you would be properly entitled to the master’s bonnet you are

wearing.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Gil, torn between annoyance, embarrassment and admiration. Patrick Elphinstone nodded, and turned to look out at the weather.

‘Aha! I think it’s easing a bit. Amid, scholastici,’ he said, pitching his voice without difficulty to reach all ears above the buzz of conversation. ‘We can set

out now. Full academic dress, I remind you. The rain is no excuse. Shall we go, Principal?’

Bowing politely to one another, the two men stepped into the drizzle to descend the stair to the courtyard.

‘All right for him,’ muttered a voice behind Gil as the Masters of Arts followed on. ‘The number of benefices he’s got, he can afford a new gown every week if he

wants.’

‘He’ll hear you,’ said Gil, turning to look into the black-browed, long-jawed face at his shoulder. ‘Is that you, Nick? I thought I knew the voice.’

‘Aye, Gil.’ Nicholas Kennedy, Master of Arts, grinned briefly at him. They slipped into place behind the last of the graduates, and Maister Kennedy continued, ‘You’re not

too grand to speak to me, then, having been to Paris and all that?’

‘I would be,’ Gil responded, ‘but you heard the Dean. I’m not entitled to this bonnet, and I take it you are.’

‘Christ aid, yes.’ His friend grimaced, his shaggy brows twitching. ‘Course of twenty lectures to the junior bachelors on Peter of Spain. This makes the fourth year I’ve

delivered it. What an experience. I tell you, Gil,’ he said, making for the horses ahead of his place in the order of precedence, ‘the man who invented the regenting system was probably

a torturer in his spare time.’ He hitched gown and cassock round his waist and swung himself into the wet saddle. ‘Did one of the songmen tell me you’re betrothed? Is that what

the Dean was on about? I thought you were for the priesthood and the Law, like the Dean said.’

‘That’s right,’ said Gil, standing in his stirrups so that he could bundle the skirt of his own cassock to protect his hose. ‘It’s all changed. Married life awaits

me. My uncle and Peter Mason are working out the terms, and we hope to sign the contract this week or next.’

‘And that’s you set up for life. Congratulations, man. You always did have all the luck,’ said his friend enviously. ‘God, what I’d give to get out of this place,

chaplain to some quiet old lady somewhere, never see another student in my life.’ He stared round, and nodded at a knot of students in their belted gowns of red or blue or grey. ‘That

lot, for instance. They’ll sing Mass for us like angels, Bernard Stewart’ll make sure of that, but they’re a bunch of fiends, I tell you. If we get through the entertainment

without someone deliberately fouling things I’ll buy the candles for St Thomas’s for the year. Oh, God, there’s William.’

‘The entertainment,’ repeated Gil. ‘I’d forgotten the entertainment. Don’t tell me you’re in charge, Nick?’

‘Very well, I won’t,’ said Nick, ‘but I am. For my sins.’

‘What are you giving us?’

‘Oh, it’s a play, as prescribed. I won’t tell you any more,’ said Nick rather sourly. ‘I don’t want to raise your expectations. What does your minnie say

about your marriage? I mind she had other plans for you.’

‘She’ll come round to it,’ said Gil, uncomfortably reminded of Alys’s remark about his mother’s letter.

With much shuffling and jostling, and delays caused by people struggling back into gown and hood and retrieving felt caps dislodged in the process, the Faculty got itself on horseback and

arranged in order. The University Beadle, peering back along the line, nodded, raised his hat to the Dean, and gave the signal to move off as the sun came out again.

Clattering up the High Street, Gil hitched at the layers of worsted he had wadded to sit on, and looked around at the other Faculty members present. At the head of the procession the Beadle was

attended by a handful of senior students, presumably all those who could muster a horse and gown for the occasion. Demure behind them, decked in the Faculty’s collection of blue academic

hoods, rode a favoured five of the non-regent Masters, followed closely by those other Masters of Arts who, like Gil, were living in the burgh and had been unable to avoid the requirement to

attend, and Maister Kennedy, quite out of his proper position. The Faculty’s Man of Law and Scribe, side by side in their red legal robes, were succeeded by someone Gil did not know, who must

be the Second Regent, and beside him baby-faced old Thomas Forsyth, his tonsure hidden by a round felt hat with a stalk like an apple’s. Behind them rode the Dean and the Principal, with four

college servants in blue velvet, and bringing up the rear, wearing the expression of a man who knows disasters are happening in his absence, was John Shaw the Faculty Steward on a fat pony. Some

way behind him rattled a donkey-cart laden with the green branches which would be handed out at St Thomas Martyr’s.

‘Why do we have the Beadle with us?’ Gil asked Nick Kennedy. ‘He’s a University servant and this is an Arts Faculty affair.’

‘Ah, but John Doby is Rector this year,’ Nick pointed out, ‘and John Gray as Beadle is the Rector’s servant. So we invited him along to make the procession look good, and

quite incidentally to lend us the tapestries and cushions he keeps for graduations. Half our costumes for the play are out of his store,’ he added.

The procession clopped and jingled up through the town. Dogs barked, and several small boys ran alongside shouting rude remarks, until Dean Elphinstone himself identified one by name and

promised to call on his father.

‘That man is an asset to the college,’ Gil observed to Nick Kennedy.

‘Oh, he is. You should see him in Faculty meeting. He has all those old men following him like an ox-team, and Tommy Forsyth and John Goldsmith agreeing with one another. He’s some

kind of cousin of William Elphinstone in Aberdeen, and you can see the resemblance.’

‘And who is that riding beside Maister Forsyth?’

Nick twisted round in time to see the man in question put out a hand to Maister Forsyth’s bridle as the horses lurched up the steep portion of the High Street called the Bell o’ the

Brae.

‘That’s Patey Coventry the Second Regent. He’s from Perthshire somewhere. A madman. He’s all right.’

‘Mad? How so?’

‘He’s Master of Arts from some obscure foreign place, he’s already collected a Bachelor of Decreets from St Andrews, and now he’s working on a Bachelor of Sacred Theology

here as well as delivering a full set of lectures and disputations. Says he just likes learning.’ Nick hauled on his reins as his horse attempted to go down the vennel that led to its stable.

‘Get on, you stupid brute, we’ve a way to go yet!’

Past the Girth Cross, past the almshouses of St Nicholas’ Hospital, past the Archbishop’s castle, the procession continued. Residents of the upper town, cathedral . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...