- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

At the May Day dancing at Glasgow Cross, Gil Cunningham sees not only the woman who is going to be murdered, but her murderer as well. Gil is a recently qualified lawyer whose family still expect him to enter the priesthood. When he finds the body of a young woman in the new building at Glasgow Cathedral he is asked to investigate, and identifies the corpse as the runaway wife of cruel, unpleasant nobleman John Semphill. With the help of Maistre Pierre, the French master-mason, Gil must ask questions and seek a murderer in the heart of the city.

Release date: September 1, 2011

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 278

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

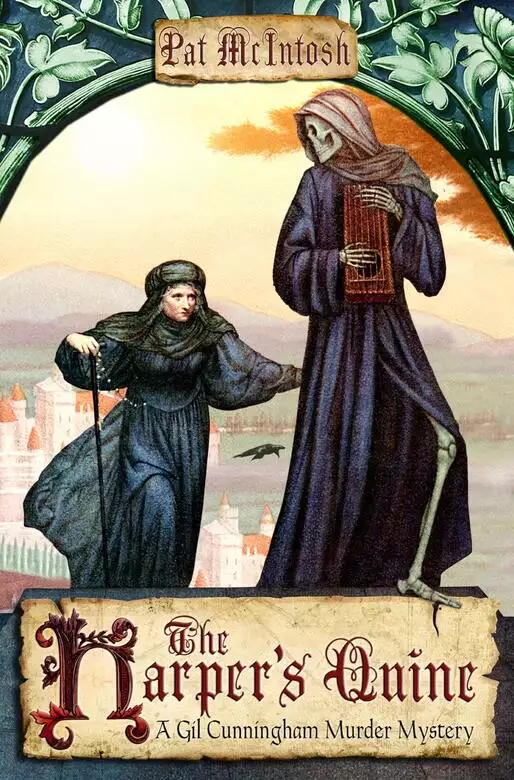

The Harper's Quine

Pat McIntosh

Glasgow, 1492

At the May Day dancing at Glasgow Cross, Gilbert Cunningham saw not only the woman who was going to be murdered, but her murderer as well.

Strictly speaking, he should not have been there. Instead he should have been with his colleagues in the cathedral library, formulating a petition for annulment on grounds which were quite

possibly spurious, but shortly after noon he had abandoned that, tidied his books into a neat stack in his carrel, with Hay on Marriage on the top, and walked out. A few heads turned as he

went, but nobody spoke.

Descending the wheel stair, past the silent chambers of the diocesan court, he stepped out into the warm day enjoying the feeling of playing truant and closed the heavy door without stopping to

read the notices nailed to it. The kirkyard was busy with people playing May-games, running, catching, shrieking with laughter. Gil went out, past the wall of the Archbishop’s castle, and

jumped the Girth Burn ignoring the stepping stones. From here, already, he could hear the thud, thud of the big drum, like the muffled beat for a hanging.

There was plenty of movement in the steep curving High Street too. Weary couples, some still smelling of smoke from the bonfires, were returning home in the sunshine with their wilting branches.

Others, an honest day’s work at least attempted, were hurrying from the little thatched cottages to join the fun. Hens and dogs ran among the feet of the revellers, and a tethered pig outside

one door had a wide empty space round it.

Further down, where the slope eased and the houses were bigger, a group of students were playing football under the windows of the shabby University building, shouting at each other in mixed

Latin and Scots. Gil nodded to the solemn Dominican who was guarding the pile of red and blue gowns, and skirted the game carefully with the other passers-by. Beyond the noise of the players and

onlookers he could hear the drum again, together with the patter of the tabor and a confused sound of loud instruments which came to a halt as he drew near to the Tolbooth.

At the Mercat Cross there was clapping and laughter. The dancers were still in the centre of the crossing, surrounded by a great crowd. More people lined the timber galleries of the houses,

shouting encouragement, and several ale-wives who had brought barrels of ale down on handcarts were doing a brisk trade.

The burgh minstrels on the Tolbooth steps, resplendent in their blue coats under an arch of hawthorn branches, had added a man with a pipe and tabor and a bagpiper to the usual three shawms and

a bombard. As Gil reached the mouth of the High Street they struck up a cheerful noise just recognizable as ‘The Battle of Harlaw’.

‘A strange choice for the May dancing,’ he remarked to the man next to him, a stout burgess in a good cloth gown with his wife on his arm. ‘Oh, it’s yourself,

Serjeant,’ he added, recognizing the burgh’s chief lawkeeper. ‘Good day to you, Mistress Anderson.’

Mistress Anderson, more widely known as Mally Bowen the burgh layer-out, bobbed him a neat curtsy, the long ends of her linen kerchief swinging, and smiled.

‘The piper only has the two tunes,’ explained Serjeant Anderson, ‘that and “The Gowans are Gay”, and they’ve just played the other.’

‘I see,’ said Gil, looking over the heads at the top dancers advancing to salute their partners, while more couples pushed and dragged one another into position further down the

dance. By the time all were in place the top few were already linking arms and whirling round with wild war-cries. A far cry from Aristotle’s ideal, he thought.

‘It’s a cheery sound, yon,’ said Gil’s neighbour in his stately way. Gil nodded, still watching the dancers. Most were in holiday clothes, some in fantastic costume from

the pageant, or with bright bunches of ribbon or scraps of satin attached to their sleeves. Many of the girls, their hair loose down their backs, were garlanded with green leaves and flowers, and

their married sisters had added ribbons to their linen headdresses. Students from the College, sons of burgesses in woollen, prentice lads in homespun, swung and stamped to the raucous music.

Watching a pair of students in their narrow belted gowns, crossing hands with two girls who must be sisters, Gil tried to reckon when he had last danced at the Cross himself. It must be eight

years, he decided, because when he first returned to Scotland his grief and shock had kept him away, and last year he had been hard at work for his uncle on some case or other. He found his foot

tapping.

‘See her,’ said the serjeant, indicating a bouncing, black-browed girl just arming with a lad in brown doublet and striped hose. ‘Back of her gown’s all green. Would ye

take a wager she’s doing penance for last night’s work next Candlemas, eh, Maister Cunningham?’

‘Oh, John!’ said his wife reproachfully.

‘She’ll not be the only one, if so,’ Gil observed, grinning. ‘There’s a few green gowns here this morning.’

‘And I’ll wager, this time o’ year, Maister Cunningham, you wish you were no a priest,’ added the serjeant, winking slyly up at Gil.

‘Now, John!’

‘I’m not a priest,’ said Gil. Not yet, said something at the back of his mind, as he felt the familiar sinking chill in his stomach. When the man looked sceptically at his

black jerkin and hose, he added reluctantly, ‘I’m a man of law.’

‘Oh, so I’ve heard said. You’ll excuse me, maister,’ said Serjeant Anderson. ‘I’ll leave ye, afore ye charge me for the time of day. Come on, hen.’

‘I’m at leisure today,’ Gil said, but the serjeant had drawn his wife away. Gil shrugged, and turned his attention back to the dancing. The couple he had been watching had

completed their turn of the dance and were laughing together, the boy reaching a large rough hand to tug at the girl’s garland of flowers. She squealed, and ducked away, and just then the

tune reached an identifiable end and the musicians paused for breath. The man banging the big drum kept on going until the tenor shawm kicked him. He stopped, blinking, and the dancers milled to a

halt.

Gil took advantage of the general movement to climb a few steps up the nearest fore-stair, where several people were already perched out of reach of the elbows and feet of the mob.

‘More!’ shouted someone. ‘Anither tune!’

The band made its reluctance clear. A short argument developed, until someone else shouted, ‘The harper – fetch the harper!’

‘Aye, the harper!’ agreed several voices at once. The cry was taken up, and the band filed down the steps, carrying its instruments, and headed purposefully for the nearest

ale-wife’s trestle.

‘This will be good,’ said someone beside Gil. He looked round, and found the next step occupied by a tall, slender girl with a direct brown gaze above a narrow hatchet of a nose.

‘The harper,’ she added. ‘Have you heard him? He has two women that sing.’

‘No, I haven’t,’ he admitted, gazing appreciatively.

‘They sang Greysteil at the Provost’s house at Yule.’

‘What, the whole of it? All four thousand lines?’

She nodded. ‘It took all afternoon. It was Candlemas before the tune went out of my head.’

‘I have never heard it complete. There can’t be many singers could perform it like that.’

‘They took turns,’ she explained, ‘so neither voice got tired, and I suppose neither needed to learn the whole thing. One of them had her baby with her, so she had to stop to

nurse it.’

‘What about the audience?’ said Gil.

The brown eyes danced. ‘We could come and go,’ she pointed out. ‘I noticed the Provost found duties elsewhere in his house.’

‘And his lady?’ said Gil, half at random, fascinated by her manner. She was dressed like a merchant’s daughter, in well-cut brown linen faced with velvet, and she was clearly

under twenty, but she spoke to him as directly as she looked, with none of the archness or giggling he had encountered in other girls of her class. Moreover, she was tall enough to look nearly

level at him from the next step up. What was that poem some King of Scots wrote in captivity? The fairest or the freschest yong flower That ever I saw, me thocht, before that hour. It seemed

to fit.

‘Lady Stewart had to stay,’ she acknowledged. ‘I thought she was wearying by the end of the afternoon.’

She spoke good Scots with a slight accent which Gil was still trying to place when there was a disturbance beyond the Tolbooth, and the crowd parted to make way for three extraordinary figures.

First to emerge was a sweet-faced woman in a fashionably cut dull red gown and a newfangled French hood, who carried a harper’s chair. After her came another woman, tall and gaunt, her black

hair curling over her shoulders, pacing like a queen across the paved market-place in the loose checked dress of a Highlander. In one arm she clasped a harp, and on the other she led a man nearly

as tall as Gil. He wore a rich gown of blue cloth, in which he must have been uncomfortably warm, a gold chain, and a black velvet hat with a sapphire in it. Over chest and shoulders flowed long

white hair and a magnificent beard. At the sight a child on its father’s shoulders wailed, ‘Set me down, Da, it’s God the Faither! He’ll see me!’

The harper was guided up the Tolbooth steps, seated himself with great dignity, accepted harp and tuning-key, and as if there was not a great crowd of people watching, launched into a formal

tuning prelude.

‘How the sound carries,’ Gil said.

‘Wire strings,’ said the girl. ‘I’m surprised you haven’t heard him before. Did he not play when the King stayed with the Bishop last winter? Archbishop,’ she

corrected herself.

‘My uncle mentioned a harper,’ Gil recalled.

‘I thought you would have attended him,’ she said. ‘The Official of Glasgow is important, no? He is the senior judge of the diocese? His nephew should be present to give him

consequence.’

‘You know me?’ said Gil in French, suddenly placing her accent.

‘My nurse – Catherine – knows everyone,’ she answered enigmatically. ‘Hush and listen.’

The Highland woman on the Tolbooth steps was arguing with some of the crowd, apparently about what they were to sing. The other was watching the harper, who, face turned unseeing towards the

Waulkergait, continued to raise ripples of sound from the shining strings. Suddenly he silenced the instrument with the flat of his hand, and with a brief word to the women began to play the

introduction to a May ballad. They took up the tune without hesitation, the two voices echoing and answering like birds.

Gil, listening raptly, thought how strong was the rapport between the three musicians, in particular the link between the blind man and the woman in the red dress. When the song ended he turned

to his companion.

‘My faith, I’ve heard worse in Paris,’ he said over the crowd’s applause.

‘You know Paris? Were you there at the University?’ she said, turning to look at him with interest. ‘What were you studying? When did you leave?’

‘I studied in the Faculty of Laws,’ he answered precisely, ‘but I had to come home a couple of years since – at the end of ’89.’

‘Of course,’ she said with ready understanding, ‘the Cunninghams backed the old King in ’88. Were all the lands forfeit since the battle? Are you left quite

penniless?’

‘Not quite,’ he said stiffly, rather startled by the breadth of her knowledge. She gave him a quick apologetic smile.

‘Catherine gossips. What are they playing now? Aren’t they good? It is clear they are accustomed to play together.’

The Highlander woman had coaxed the taborer’s drum from him, and was tapping out a rhythm. The other woman had begun to sing, nonsense syllables with a pronounced beat, her eyes sparkling

as she clapped in time. Some of the crowd were taking up the clapping, and the space before the Tolbooth was clearing again.

‘Will you dance?’ Gil offered, to show that he had not taken offence. The apologetic smile flashed again.

‘No, I thank you. Catherine will have a fit when she finds me as it is. Oh, there is Davie-boy.’ She nodded at the two youngsters Gil had been watching earlier. ‘I see he has

been at the May-games. He is one of my father’s men,’ she explained.

The dancers had barely begun, stepping round and back in a ring to the sound of harp, tabor and voice, when there was shouting beyond the Tolbooth, and two men in helmets and quilted jacks rode

round the flank of the Laigh Kirk.

‘Way there! Gang way there!’

The onlookers gave way reluctantly, with a lot of argument. More horsemen followed, well-dressed men on handsome horses, and several grooms. Satin and jewels gleamed. The cavalcade, unable to

proceed, trampled about in the mouth of the Thenawgait, with more confused shouting.

‘Who is it?’ wondered Gil’s companion, standing on tiptoe to see better.

‘You mean Catherine did not expect them?’ he asked drily. ‘That one on the roan horse is some kind of kin of mine by marriage, more’s the pity – John Sempill of

Muirend. He must have sorted out his little difficulty about Paisley Cross. That must be his cousin Philip behind him. Who the others might be I am uncertain, though they look like Campbells, and

so do the gallowglasses. Oh, for shame!’

The men-at-arms had broken through the circle of onlookers into the dancing-space, and were now urging their beasts forward. The dancers scattered, shouting and shaking fists, but the rest of

the party surged through the gap and clattered across the paving-stones to turn past the Tolbooth and up the High Street.

Immediately behind the men-at-arms rode Sempill of Muirend on his roan horse, sandy-haired in black velvet and gold satin, a bunch of hawthorn pinned in his hat with an emerald brooch, scowling

furiously at the musicians. After him, the pleasant-faced Philip Sempill seemed for a moment as if he would have turned aside to apologize, but the man next him caught his bridle and they rode on,

followed by the rest of the party: a little sallow man with a lute-case slung across his back, several grooms, one with a middle-aged woman behind him, and in their midst another groom leading a

white pony with a lady perched sideways on its saddle. Small and dainty, she wore green satin trimmed with velvet, and golden hair rippled down her back beneath the fall of her French hood. Jewels

glittered on her hands and bosom, and she smiled at the people as she rode past.

‘Da!’ said the same piercing little voice in the crowd. ‘Is that the Queen of Elfland?’

The lady turned to blow a kiss to the child. Her gaze met Gil’s, and her expression sharpened; she smiled blindingly and blew him a kiss as well. Puzzled and embarrassed, he glanced away,

and found himself looking at the harper, whose expressionless stare was aimed at the head of the procession where it was engaged in another argument about getting into the High Street. Beside him,

the tall woman in the checked gown was glaring malevolently in the same direction, but the other one had turned her head and was facing resolutely towards the Tolbooth. What has Sempill done to

them? he wondered, and glancing at the cavalcade was in time to see Philip Sempill looking back at the little group on the steps as if he would have liked to stay and listen to the singing.

‘Who is she?’ asked Gil’s companion. ‘Do you know her?’

‘I never saw her before.’

‘She seemed to know you. Whoever she is,’ said the girl briskly, ‘she’s badly overdressed. This is Glasgow, not Edinburgh or Stirling.’

‘What difference does that make?’ Gil asked, but she gave him a pitying glance and did not reply. The procession clattered and jingled away up the High Street, followed by resentful

comments and blessings on a bonny face in roughly equal quantities. The dance re-formed.

‘What is a gallowglass?’ said the girl suddenly. Gil looked round at her. ‘It is a word I have not encountered. Is it Scots?’

‘I think it may be Ersche,’ Gil explained. ‘It means a hired sword.’

‘A mercenary?’

‘Nearly that. Your Scots is very good.’

‘Thank you. And now if you will let me past,’ she added with a glance at the sun, ‘I will see if I can find Catherine. She was to have come back for me.’

‘May I not convoy you?’ suggested Gil, aware of a powerful wish to continue the conversation. ‘You shouldn’t be out unattended, today of all days.’

‘I can walk a few steps up the High Street without coming to grief. Thank you,’ she said, and the smile flickered again. She slipped past him and down the steps before he could argue

further, and disappeared into the crowd.

The harper was playing again, and the tall Highlander woman was beating the tabor. The other woman was singing, but her head was bent and all the sparkle had gone out of her. The fat wife who

was now standing next to Gil nudged him painfully in the ribs.

‘That’s a bonny lass to meet on a May morning,’ she said, winking. ‘What did you let her go for? She’s a good age for you, son, priest or no.’

‘Thank you for the advice,’ he said politely, at which she laughed riotously, nudged him again, and began to tell him about a May morning in her own youth. Since she had lost most of

her teeth and paused to explain every name she mentioned Gil did not attempt to follow her, but nodded at intervals and watched the dance, his pleasant mood fading.

That was twice this morning he had been taken for a priest. It must be the sober clothes, he thought, and glanced down. Worn boots, mended black hose, black jerkin, plain linen shirt, short gown

of black wool faced with black linen. Maybe he should wear something brighter – some of the Vicars Choral were gaudy enough. It occurred to him for the first time that the girl had not

addressed him as a priest, either by word or manner.

He became aware of a disturbance in the crowd. Leaning out over the handrail he could see one man in a tall felt hat, one in a blue bonnet, both the worse for drink and arguing over a girl.

There was a certain amount of pulling and pushing, and the girl exclaimed something in the alarmed tones which had caught his attention. This time he knew the voice.

The stair was crowded. He vaulted over the handrail, startled a young couple by landing in front of them, and pushed through the people, using his height and his elbows ruthlessly. The man in

the hat was dressed like a merchant’s son, in a red velvet doublet and a short gown with a furred collar caked in something sticky. The other appeared to be a journeyman in a dusty jerkin,

out at the elbows. As Gil reached them, both men laid hold of his acquaintance from the stairway, one to each arm, pulling her in opposite directions, the merchant lad reaching suggestively for his

short sword with his other hand.

This could be dealt with without violence. Gil slid swiftly round behind the little group, and said clearly, ‘Gentlemen, this is common assault. I suggest you desist.’

Both stared at him. The girl twisted to look at him over her shoulder, brown eyes frightened.

‘Let go,’ he repeated. ‘Or the lady will see you in court. She has several witnesses.’ He looked round, and although most of the onlookers suddenly found the dance much

more interesting, one or two stalwarts nodded.

‘Oh, if I’d known she kept a lawyer,’ said the man in the hat, and let go. The other man kept his large red hand on the girl’s arm, but stopped pulling her.

‘It’s all right, Thomas,’ she said breathlessly. ‘This gentleman will see me home.’

‘You certain?’ said Thomas indistinctly. ‘Does he ken where ’tis?’ She nodded, and he let go of her wrist and stepped back, looking baffled. ‘You take her

straight home,’ he said waveringly to Gil. ‘Straight home, d’you hear me?’

‘Straight home,’ Gil assured him. ‘You go and join the dancing.’ If you can stay upright, he thought.

Thomas turned away, frowning, at which the man in the hat also flounced off into the crowd. The girl closed her eyes and drew a rather shaky breath, and Gil caught hold of her elbow.

‘This time I will convoy you,’ he said firmly.

She took another breath, opened her eyes and turned to him. He met her gaze, and found himself looking into peat-brown depths the colour of the rivers he had swum in as a boy. For an infinite

moment they stared at one another; then someone jostled Gil and he blinked. Recovering his manners, he let go of her elbow and offered his arm to lead her.

She nodded, achieved a small curtsy, and set a trembling hand on his wrist. He led her out of the crowd and up the High Street, followed by a flurry of predictable remarks. He was acutely aware

of the hand, pale and well-shaped below its brown velvet cuff, and of her profile, dominated by that remarkable nose and turned slightly away from him. The top of her head came just above his

shoulder. Suppressing a desire to put his arm round her as further support, or perhaps comfort, he began a light commentary on the music which they had heard, requiring no answer.

‘Thomas was trying to help,’ she said suddenly. ‘He saw Robert Walkinshaw accost me and came to see him off.’

‘Is he another of your father’s men?’ Gil asked. ‘He’s obviously concerned for you.’

‘Yes,’ she said after a moment, and came to a halt. Although she still trembled she was not leaning on his wrist at all. He looked down at her. ‘And this is my father’s

house. I thank you, Maister Cunningham.’

She dropped another quick curtsy, and slipped in at the pend below a swinging sign. At the far end of the tunnel-like entry she turned, a dark figure against the sunlit court, raised one hand in

salute, then stepped out of sight. Gil, troubled, watched for a moment, but she did not reappear. He stepped backwards, colliding with a pair of beribboned apprentices heading homeward.

‘Whose house is that?’ he asked them.

‘The White Castle?’ said one of them, glancing at the sign. ‘That’s where the French mason lives, is it no, Ecky?’

Ecky, after some thought, agreed with this.

‘Aye,’ pursued his friend, who seemed to be the more wide awake, ‘for I’ve taken a pie there once it came out the oven. There’s an auld French wife there

that’s the devil to cross,’ he confided to Gil. ‘Aye, it’s the French mason’s house.’

They continued on their way. Gil, glancing at the sun, decided that he should do likewise. Maggie Baxter had mentioned something good for dinner.

Canon David Cunningham, Prebendary of Cadzow, Official of Glasgow, senior judge of the Consistory Court of the archdiocese, was in the first-floor hall of his handsome stone

house in Rottenrow. He was seated near the window, tall and lean like Gil in his narrow belted gown of black wool, with a sheaf of papers and two protocol books on a stool beside him. In deference

to the warmth of the day, he had removed his hat, untied the strings of his black felt coif, and hung his furred brocade over-gown on the high carved back of his chair. Gil, bowing as he entered

from the stair, discovered that his head was bare in the same moment as his uncle said,

‘Where is your hat, Gilbert? And when did you last comb your hair?’

‘I had a hat when I went out,’ he said, wondering at the ease with which the old man made him feel six years old. ‘It must have fallen off. Perhaps when I louped the

handrail.’

‘Louped the handrail,’ his uncle repeated without expression.

‘There was a lass being molested.’ Gil decided against asking when dinner was, and instead nodded at his uncle’s papers. ‘Can I help with this, sir?’

‘You are six-and-twenty,’ said his uncle. ‘You are graduate of two universities. You are soon to be priested, and from Michaelmas next, Christ and His Saints preserve us, you

will be entitled to call yourself a notary. I think you should strive for a little dignity, Gilbert. Yes, you can help me. I am to hear a matter tomorrow – Sempill of Muirend is selling land

to his cousin, and we need the original disposition from his father. It should be in one of these.’ He waved a long thin hand at the two protocol books.

‘That would be why I saw him riding into the town just now. What was the transaction, sir?’ Gil asked, lifting one of the volumes on to the bench. His uncle pinched the bridge of his

long nose and stared out of the window.

‘Andrew Sempill of Cathcart to John Sempill of Muirend and Elizabeth Stewart his wife, land in the burgh of Glasgow, being on the north side of Rottenrow near the Great Cross,’ he

recited. ‘Just across the way yonder,’ he added, gesturing. ‘I wonder if he’s taken his wife back?’

‘His wife?’ said Gil, turning pages. ‘You know my mother’s sister Margaret was married on Sempill of Cathcart? Till he beat her and she died of it.’

‘Your mother’s sister Margaret never stopped talking in my hearing longer than it took to draw breath,’ said his uncle. ‘Your sister Tibby is her image.’

‘So my mother has often said,’ agreed Gil.

‘There is no proof that Andrew Sempill gave his wife the blow that killed her. She was his second wife, and there were no bairns. John Sempill of Muirend would be his son by the first

wife. She was a Walkinshaw, which would be how they came by the land across the way. I think she died of her second bairn.’

‘And what about John Sempill’s wife?’ Gil persisted.

‘You must not give yourself to gossip, Gilbert,’ reproved his uncle. ‘Sempill of Muirend married a Bute girl. While you were in France, that would be. She and her sister were

co-heirs to Stewart of Ettrick, if I remember. She left Sempill.’

‘There was a lady with him when he rode in just now.’ Gil turned another page, and marked a place with his finger. ‘Dainty creature with long gold hair. Child in the crowd

thought she was the Queen of Elfland.’

‘That does not sound like his wife.’

‘It’s not his wife.’ Maggie Baxter, stout and red-faced, appeared in the doorway from the kitchen stair. ‘Will ye dine now, maister? Only the May-bannock’s like to

spoil if it stands.’

‘Very well.’ The Official gathered up his papers. ‘Is it not his wife, Maggie?’

‘The whole of Glasgow kens it’s not his wife,’ said Maggie, dragging one of the trestles into the centre of the hall, ‘seeing she’s taken up with the harper that

stays in the Fishergait.’

‘What, t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...