- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

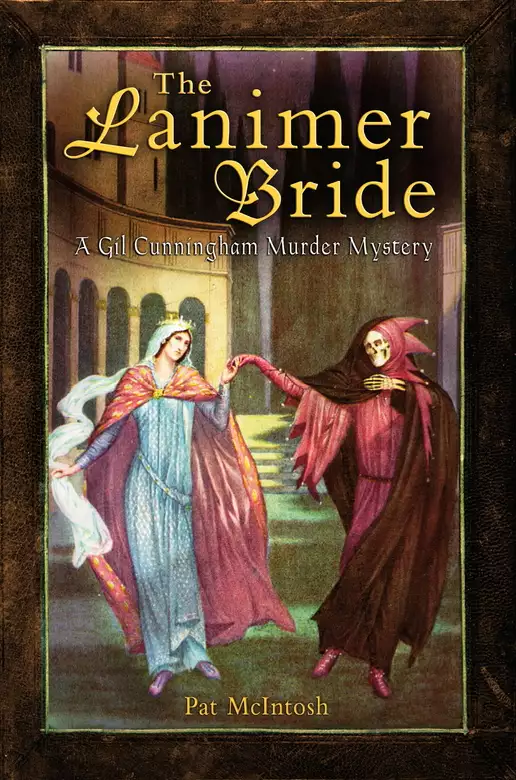

How could the heavily-pregnant bride of the lanimer-man vanish into thin air? Young Mistress Audrey Madur is missing and her husband, responsible for maintaining boundaries and overseeing land use in the burgh of Lanark, is strangely reluctant to search for her. Gil Cunningham, answering the frantic appeal of Audrey's mother, finds himself searching the burgh and the lands round about, questioning family and neighbours. He and Alys uncover disagreements, feuds, adultery and murder, and encounter once again the flamboyant French lady Olympe Archibecque, who is not at all what she seems. And then another lady goes missing . . . Praise for Pat Macintosh: 'Will do for Glasgow in the fifteenth century what Ellis Peters and her Brother Cadfael did for Shrewsbury in the twelfth' Mystery Reader's Journal.

Release date: July 7, 2016

Publisher: Constable

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lanimer Bride

Pat McIntosh

The weather was unusually warm for a Scottish summer, and the airs of Glasgow had been close and muggy for days. Alys, discovering a week since that measles was abroad in the burgh, had packed up most of the household, including Gil’s small ward John McIan, and removed to the fresher air of Carluke. It had taken Gil a few days to deal with the outstanding work on his desk, and he had only just been able to follow her, leaving his young assistant to mind the legal practice and Alys’s aged companion to mind the house.

‘It’s much healthier up here,’ Alys observed, gazing up into the quince tree, the sunlight edging the high bridge of her nose. ‘The air is cleaner, and there are breezes. Look, there will be a good crop this year. Your mother has promised me some quince leather.’

‘True,’ said Gil to her first statement. ‘And there have been deaths in the lower town. Your father is very concerned for Ealasaidh and the boy. You were wise to leave Glasgow. Is John behaving?’

She turned to look at him, brown eyes dancing.

‘Do you think he can behave? He went after the cockerel’s tail feathers yesterday, such a squawking and shrieking in the henyard you never heard. Alan wished me to beat him, but your mother only laughed. I think Alan fears John will lead his boy into trouble.’

‘Very likely,’ said Gil, grinning. ‘I remember raiding the henyard for feathers too. They make rare plumes for a helmet.’

‘Maister Gil!’ a voice called under the trees. ‘Mistress?’

‘We’re here, Alan,’ Gil answered, and turned to stroll towards the orchard gate. ‘What’s he done now?’

Lady Cunningham’s steward appeared, hot and flustered in his gown of office, shaking his head.

‘It’s no the wee boy, maister, it’s Mistress Somerville from Kettlands, over by Lanark, wanting a word.’

‘Somerville,’ Gil repeated as he reached the man. ‘Come under the shade and catch your breath, it’s ower hot to be hurrying. Is that Yolande Somerville? James Madur’s widow? What’s she after?’

‘Aye, that’s the lady.’ Alan Forrest fanned himself with his straw hat, but drew gratefully into the shade. ‘Mistress.’ He bent the knee briefly to Alys. ‘She wedded her youngest lassie a year back, a plain quiet lass, no a great dower seeing her daddy’s gone, so Mistress Somerville took the lanimer man from Lanark for her.’

‘What, Brosie Vary? That’s no such a bad bargain,’ Gil said in surprise. ‘I’d ha thought he could do better than that in the burgh. He was a couple of years ahead of me at the college in Glasgow,’ he added to Alys. ‘He’ll be past thirty by now, and well established.’

‘Well, no,’ Alan said awkwardly, carefully not looking at Alys again. ‘He’s a younger son, after a’, and buried three wives a’ready, two in childbed, one fell sick while she was carrying. They’re a bit wary o him in Lanark now, or so I hear. Any road,’ he said, returning to the point, ‘his wife, Mistress Somerville’s lassie’s missing and she wants a word wi you.’

‘Missing?’ Alys repeated in astonishment. ‘What, has she run away?’

‘Mistress Somerville says no,’ said Alan.

‘What does Vary say?’ Gil asked, opening the orchard gate for Alys to pass through. ‘Is he here? What’s it all about, anyway?’

‘Maister Vary’s no present,’ said Alan in neutral tones. He turned to close and bolt the gate, and added with no more expression, ‘Best if Mistress Somerville lets you have the tale hersel. She’s wi the mistress the now.’

Gil looked at Alys, raising his eyebrows. Presumably his mother was taking this seriously, if she had sent Alan to fetch him in.

Egidia Muirhead, Lady Cunningham, was seated in the hall of her tower-house, very upright on the oak settle by the cavernous empty fireplace, her stout maidservant Nan watchful by the wall. The chatelaine of Belstane was wearing an elderly but still respectable wrapped gown of fine dark red wool, suitable for the warm weather, with her second-best girdle about her waist, the one shod with silver and garnets, and an old-fashioned flowerpot headdress from which wisps of iron-grey hair escaped under her fine linen veil. The gown was clasped on the breast with the jewelled badge of her service in the late Queen’s household. Gil recognised that his mother had had warning of this guest and dressed to make a statement. She could command respect wearing muddy boots and one of her dead husband’s old gowns; like this she was magnificent.

Opposite her was a rather different lady. Short and plump, she was clad in fashionable black silk brocade, with extravagant cuffs on her tight sleeves. A braid-trimmed French hood and black velvet veil were clamped down over a snowy cap; a finely pleated barbe probably concealed more than one extra chin, and a thick layer of dust powdered all above her waist. She was accompanied by a scrawny maid and a groom in velvet livery.

As Gil and Alys entered the hall she was almost bouncing up and down on her padded backstool, saying in agitated tones, ‘But where can she be? Vary’s no concerned, but I ken my lass, madam, I ken what she’d be like to do, and where would she go in her state anyway?’ She gestured down her own ample front, describing a swollen belly. By the empty hearth Socrates the wolfhound, sleeping off the twenty-mile journey of the morning, did not stir at Gil’s footstep.

‘When’s the groaning-ale to be brewed for?’ Lady Egidia asked delicately. ‘Has she long to go?’

‘Four weeks, no more, that’s why I’m—’ Mistress Somerville shook her head so that the barbe swept to and fro across her bosom. ‘She wouldny— and any road, what, where would, who would—’

‘Gil,’ said Lady Egidia in some relief, catching sight of her son. ‘And Alys. Mistress Somerville, have you met my good-daughter?’

In the little flurry of presentation, bowing and curtsying, one of the servants entered with a tray. Alys sat down beside her mother-in-law, and while Gil poured well-water with fruit vinegar and handed the platter of little cakes, she said, ‘What has happened, madam? It sounds very serious.’

‘Oh, aye, it’s serious, lassie.’ Mistress Somerville dabbed at her eyes with her free hand, then took two cakes as the platter passed her again. ‘My lassie’s vanished away, and no knowing what’s come to her, and her man’s no like to seek her.’

Gil looked round at this, and met Alys’s puzzled glance. He nodded agreement; something did not make sense.

‘Tell us from the beginning,’ he suggested. ‘What’s your daughter’s name, for a start?’

‘Audrey.’ Mistress Somerville took a draught of her beaker, grimaced at the acid taste, and began again. ‘Audrey Madur. My youngest. It’s no a common name, Audrey,’ she admitted. ‘It’s my grandam’s name, that was an Englishwoman from Ely or Norwich or somewhere o the sort. My lassie’s wedded on Maister Ambrose Vary, that’s notary and liner in Lanark, and her first bairn’s due in a month or so. She rid out to see me ten days since, wi her groom, young Adam, that’s been her groom since she was twelve, and she stayed a few days, but she would ride back in for the Lanimer Fair, for that it was the first anniversary o their marriage the day after it and they were to hear Mass thegither in St Nicholas’ kirk.’

‘Lanimer?’ said Alys. ‘What saint is that?’

‘Not a saint. It means a land boundary,’ said Gil. ‘They hold the fair at the same time as they ride the bounds of the burgh. It’s a great celebration, wi races and drinking and dancing. It aye falls around Pentecost. It must ha been last week, mistress?’

Mistress Somerville nodded, and dabbed at her eyes again.

‘Last Thursday,’ she confirmed, ‘that was June tenth. So she set off on that very day, to ride back to Lanark, thinking the fair wouldny be over when she got there. I waved her off, her on the wee jennet Vary bought her and Adam on the powny, and I thought no more o’t.’

‘She was riding?’ Alys said.

‘Aye, on a proper lady’s saddle, wi her feet on a foot-board and a good stout safeguard to keep the dust fro her skirts. I know what’s due to my lassie.’

Since both his mother and his wife habitually rode astride, Gil refrained from catching anyone’s eye. Instead he said, ‘And when did you learn she was missing? I take it she never reached Lanark?’

Mistress Somerville nodded again, biting her lip.

‘’Twas only yestreen. I rode in to visit wi Mistress Limpie Archibeck, that’s a French lady residing in Lanark the now, and called in at Vary’s house on my way home, seeing I was close, and I thought to see her. And the look on Vary’s face when I fetched up at his door asking for her!’

‘What did he say?’ Alys asked.

‘Oh, he denied she was there, and the servants said likewise, and then he said, Did she no stay on wi you? And I said, No, she would come in to the fair. And he said, I bade her stay till after it, I didny wish her at the fair in her state. I took it she’d minded me for once, he says.’

‘Was that all he said?’ Gil prompted, when she paused again. One part of his mind was grappling with Mistress Archibeck’s name (Archibecque? Archévecque? But what could Limpie be?) while another was trying to recall Ambrose Vary from ten years since. The image conjured up by the name was of an awkward young man with few social skills and an astounding grasp of Euclid. Attempts to get him to expound the art of mathematics to his fellows had been unsuccessful, since he had stammered and stuttered, forgotten people’s names, reacted badly to misbehaviour, and generally failed as a teacher, but it seemed to Gil that the ability would serve him well in determining boundaries and building lines.

‘Hah!’ said Mistress Somerville bitterly, and paused to take a draught of her beaker. ‘No another word did he have for me, that’s her mammy and beside mysel wi anxiety. Went into his closet wi his instruments o surveying and shut the door. When I bade them open it till I asked him what he’d do, he was just standing by his desk polishing some brass thing and never looked round.’

Gil looked at Alys, and found her round-eyed with amazement. He was considering his own possible reaction in a like situation, and found himself wondering if Vary thought his young wife had left him.

‘Do they get on well enough?’ he asked. ‘Are they fond? It wasny a love-match, I take it, he’s a deal older than she is.’

‘No, no a love-match,’ said Mistress Somerville, bridling slightly, ‘but they get on well enow for all that. She’s an obedient lassie, I raised her to be a good wife, and to ken how to manage a house to please a husband. What are you asking that for?’

A woman is a worthy wight, she serveth a man both day and night, Gil thought, and did not glance at Alys. How did it go on? And yet she hath but care and wo, that was it. Perhaps some women were content with that fate; he was sure Alys would not be.

‘No chance,’ said Lady Egidia, breaking a long silence, ‘that the groom’s run off wi her? Adam, did you say his name was? If he’s served her a long time, maybe he’s a notion to her.’

‘Nothing of the kind!’ said the other lady in rising indignation. ‘He’s a good lad, aye been a faithful servant, and besides, his leman’s saving up to their marriage. I gied her a couple of groats mysel just the other day. No, there’s some ill befallen the both o them, though what it might be I darena think, and I need you to seek for her, maister, seeing her man’s doing nothing about it.’

‘Have you sent out a search?’ Gil asked. ‘Could she have gone to any of her sisters?’

‘Oh, aye, as soon’s I reached home yestreen I sent out all the men, beating under bushes all across the muir, hunting the river banks, till it was too dark to see, and then had them out again the day morn, and one to ride to her sisters, and her brother up at Harelaw, no to mention sending to Sir John here at the kirk in Carluke, asking his prayers for us to St Malessock, as well as my own. We’ve found nothing, maister, never a trace, nor her kin’s never seen her.’

‘It’s four days,’ said Gil, ‘and it’s been dry. There’d be little to find by way of tracks, even if you ken what road they took from your house to Lanark.’

‘Never a trace,’ she reiterated. ‘Will you help me, maister? Your mammy here’s tellt me a few tales, how you’ve tracked folk down, the collier fellow, that lassie at Glasgow Cross last year and the like.’ The barbe swept across the wide black brocade bosom again as Mistress Somerville turned a pleading gaze on Gil. ‘Will you find my lassie?’

Gil raised one eyebrow at his mother, who stared back at him without comment. He was aware of Alys rising, excusing herself, slipping from the chamber, while he turned Mistress Somerville’s account over in his mind. There were several possible explanations for young Mistress Madur’s disappearance, none of them particularly good. Accident, mishap, a panicky young woman running away from something (but what?), abduction.

‘Was there anyone else had a notion to her, afore she wedded Vary?’ he asked. ‘Any that might have stolen her away? Any she might have turned to if she was alarmed or frightened?’

‘What, heavy wi another man’s bairn? Surely no!’ Mistress Somerville paused to consider, but shook her head again. ‘Her and my brother’s youngest had a liking for one another when they were younger, and made plans the way young ones do, but Somerville had other intentions for Jockie. He’s away at the College at St Andrews now, studying to be a priest. There’s been none other I can think on.’

‘Any other friends she might ha gone to?’

‘Oh, she’s friends round about,’ conceded Mistress Somerville, ‘but why would she want to do that? She was happy enough at going back to her own house, talking about the sewing she’s doing for the bairn, telling me of the cradle Vary’s ordered. I was right pleased,’ she divulged, ‘to hear he’s no looking for her to accept any of the other cradles he’s had in the house. I’d no want to see my grandchild in a dead bairn’s cradle, knowing its mammy had dee’d and all.’

‘No, indeed,’ said Lady Egidia. ‘That’s kind in him. I think he’s a good provider, mistress. It’s a good match.’

‘Mind you,’ said Mistress Somerville, ‘I hardly like to say it, but your good-brother had a notion to her at one time, maister.’

‘My good-brother?’ Gil repeated, startled, aware of his mother’s chin going up. ‘Which one? D’you mean Michael Douglas? Tib’s husband?’

‘Aye, Lady Tib’s husband. His faither Sir James had approached me, but I thought the lad ower flighty for my lassie.’

‘Oh, he’s no proved flighty as Lady Isobel’s husband,’ said Lady Egidia tartly, emphasising the name. ‘He’s steady and reliable, he and my daughter are doing well thegither, and his faither’s well pleased wi his management of the coalheugh.’ She turned her penetrating gaze on Gil. ‘I think you must lend your aid, Gil. Mistress Somerville is right anxious about her lassie. Barely a year wedded, still a bride indeed, since the bairn’s yet to be born, and gone missing like this, it would drive any mother to distraction. What a blessing you hadny got your boots off, you can ride out again as soon as our guest’s ready to leave. And Mistress Mason with you,’ she added as Alys came into the chamber from the stair, clad in her wide-skirted riding-dress. ‘Nan, will you call Alan, please, and have him send out to the stables?’

Mistress Somerville rode, like her daughter, on a lady’s saddle, perched sideways with her feet on a foot-board. She also wore a canvas safeguard to protect her skirts from the dust of the roads, and inserting her into this vast bag, fastening it about her waist, and hoisting the resulting sarpler on to the saddle took the best part of half an hour, thanks to her contrary instructions, complaints and objections.

Watching the process, Gil said quietly in French to Alys, ‘What do you make of this? It’s a strange tale.’

‘I think the girl has not left her husband of her own will,’ said Alys promptly, ‘though he fears she has.’ Gil made an agreeing sound, and she went on, ‘Your mother dislikes this woman, but she has directed you to help her. She also thinks the girl has met with a mischance, I would say.’

He glanced at his mother, standing tall and cool by the mounting-block, holding the reins of Mistress Somerville’s solid bay mule. The animal nudged her as he looked, and she obediently began caressing its soft chin, still watching the maid and two grooms assisting Mistress Somerville. Another groom hovered carefully beside her, and her own man Henry stood at a distance, ready to bring forward the Belstane horses. Next to him one of the two men Gil had brought out from Glasgow, the ubiquitous Euan Campbell, gazed round him at the bustle.

‘James Madur, the girl’s father, was injured at Sauchieburn,’ Gil said. ‘On the Prince’s side. So he got a gift of land, a customs post, other favours, and his wife was much made up by it all and boasted about it. He died a year or two after from the wound, but my mother never forgave her.’

‘I can imagine,’ said Alys. She tucked her hand into his arm. ‘How tactless, to boast in front of someone who had lost a husband and two sons on the late King’s side. Is it worth speaking to her men, to get a clearer idea of where they have searched?’

‘I was thinking that myself,’ said Gil. He succeeded, finally, in catching the eye of Mistress Somerville’s third groom, and summoned him with a jerk of his head. The man, accepting Lady Egidia’s ability to hold the mule, came over to them, ducking his head in a brief bow. He was a broad-shouldered fellow in a leather doublet, dyed the same serviceable blue as the indoor man’s velvet livery; brown hair in a neat clip showed under his woollen bonnet, and his eyes were intelligent.

‘Maister?’ he said.

‘This is a strange thing about Mistress Audrey,’ Gil said. The man simply nodded, concern in his face. ‘Have you been out with the search? Where have you covered? Was there any sign at all?’

‘No sign that I seen, none at all,’ agreed the man. ‘The roads are no that busy, but there’s enough traffic, you couldny make out what was five days old and what was seven under the dust. Her jennet’s got wee dainty feet, I thought once or twice I’d a glimp o its marks, but I lost them again.’

‘Were those on the road she’d ha taken?’

‘Oh, aye. Nothing unexpeckit.’

‘What was her groom riding?’

‘One of madam your mother’s breeding,’ the groom said, grinning awkwardly. ‘A wee sturdy bay gelding wi a sock and a star, out that bay wi the four socks she’s got.’

‘Bluebell.’ Gil nodded. ‘I’ll ken that one if I see him. Bluebell aye throws true like hersel. Did you speak to any on the road?’

‘Aye, we asked all we met had they seen them, and at the houses at the roadside and all. One fellow close to home had met wi them, about where I seen the jennet’s marks, but we’ve no more sightings this far, save for an idiot that’s talking o a lady and a battle.’

‘A battle?’ Alys repeated.

‘Aye,’ said the groom sourly. ‘Twelve big men, he says, hitting one another wi swords, and a lady cheering them on. Wasted an hour getting him to show me where it was. Turns out he canny count past three, and makes up these tales a’ the time.’

‘Was there any sign where he said the battle had been?’ Gil asked.

‘None that I could make out.’

‘Haw, Billy!’ shouted one of the grooms by the mounting-block.

‘I’ll need to go, maister,’ said Billy uneasily.

‘Aye, you will,’ Gil said. ‘I’ll get another word wi you later.’

‘A bad business this, maister,’ said Euan Campbell chattily in his ear as Billy made his way across the yard. ‘What d’you think will be coming to the lady? Is she lying dead on the moorland, maybe, or is she hidden away somewhere?’

‘That’s for us to find out,’ said Gil, his tone repressive. ‘Away and get yourself on a horse if you’re coming with us.’

Mistress Somerville was now enthroned on her saddle, her feet on the foot-board and the safeguard rising in stiff folds about her knees. Billy mounted and took her leading-rein, her maidservant was put up behind another of the grooms, and the Belstane horses were brought forward, snorting at the strange beasts, for Gil and Alys to mount. Henry and one of his minions fell in behind them, Euan joined them, Lady Egidia delivered a suitable blessing for travellers, and the cavalcade set off at a brisk walk, a speed at which Gil reckoned it would take them well over an hour to reach Kettlands.

‘You could get a word wi Mistress Somerville’s woman,’ he suggested quietly to Alys. She nodded, and began to thread her way through the procession while he turned his attention to the third Kettlands man.

This man could add little to the tale Billy had told. He had seen no trace at all of Mistress Madur’s jennet or her groom’s beast, and reckoned the girl had run off with some chance-met stranger, a pedlar or the like.

‘Stands to reason,’ he said, with a wary glance at his mistress. ‘Maister Vary’s a dry stick o a fellow, and buried three wives a’ready. No lassie’s going to stay wi a fellow like yon.’

‘You think?’ said Gil.

The present house of Kettlands, on the top of a rounded rise in the land, was quite modern, and boasted a stone ground floor with two further storeys of wood perched on top, and a tumble of outhouses within the barmekin wall. As soon as they were seen approaching several servants ran out into the road, peering anxiously under their hands; from their demeanour there was clearly no further word of Mistress Madur.

Gil, having spent the most part of the journey listening to Mistress Somerville’s alternate lamentations and accounts of her daughter’s excellence, refused her invitation to step in for a mouthful of ale.

‘I’d as soon get a look at the land and get back to Belstane while the light lasts,’ he said. ‘Show me what road they took from here, and then I think you should try to rest.’

The maidservant, just being swung down from her pillion seat, threw him a sharp glance, but Mistress Somerville took the words at face value.

‘I’ll no rest till my lassie’s returned to me, maister, but it’s kind o you to think it. They went out that way.’ She pointed south-eastward, rather than due south. The fields fell away from the barmekin wall, rolling down to a line of trees a mile or so away which Gil knew marked the valley of the Mouse Water.

‘So they went by the mill-bridge,’ he said, ‘rather than down to the crossing at Cartland Crags.’

‘Oh, a course,’ said Mistress Somerville, startled. ‘We aye use that road into Lanark, it’s closer by far.’

‘And what time was it when they left?’

‘About this time, a couple of hours afore supper.’

‘So maybe four or five hours after noon.’

‘Aye, about that.’ She rubbed tears from her eyes again. ‘She’d ha been in Lanark for her supper, so I thought. Oh, maister, find her for me. Even if her man’s no troubled about it, find her for me!’

‘The maidservant’s name is Christian,’ said Alys. ‘She says Audrey was just as usual when she was here, talking of her sewing, asking about family names to give the bairn and who might stand godparent and the like. She seemed very happy, apart from the backache.’

‘That bears out what Mistress Somerville says.’ Gil was peering down at the roadside, inspecting the drifted dust and cracked earth.

‘You see what I mean, maister,’ said Billy, twisting in the saddle to look back at them. ‘There’s no telling whether it’s marks from yesterday or marks from ten days since, aside from the jennet’s prents I showed you.’

‘So they’d ha rid along here,’ said Henry, ‘and past yon ferm-toun, Brockbank is it, Billy? And down to the Mouse past the mill. Naeb’dy at Brockbank saw them pass, then?’

‘Just this daftie I was telling you o,’ said Billy. ‘Wi his tale o a battle.’

‘Where was the battle?’ Alys asked, a moment before Gil could do so.

‘Yonder,’ Billy nodded, ‘down the banks o the Mouse. Gied me a lang tale o’t, but there was naught to be seen. Him and his twelve men!’

He spat into the dust. Gil straightened up, gazing about him.

‘They’ll be able to start the haying soon,’ he observed. ‘They might get two cuts if the weather keeps up. So there was nobody about, the same as now?’

‘A couple o folk said they was out weeding the bere and oats,’ Billy said, ‘but they never looked up. I suppose if they’d their backs to the road, maybe at the foot o the field,’ he waved at the infield where it sloped away from the track, ‘they’d never ha heard them.’

‘That’s an amazing thing,’ said Euan, ‘that anyone might pass along the road and never be noticed, let alone be spoken to.’

Ignoring this, Gil nudged his horse forward.

‘We’ll get a look at this battl. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...