The Lords of the Stoney Mountains

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

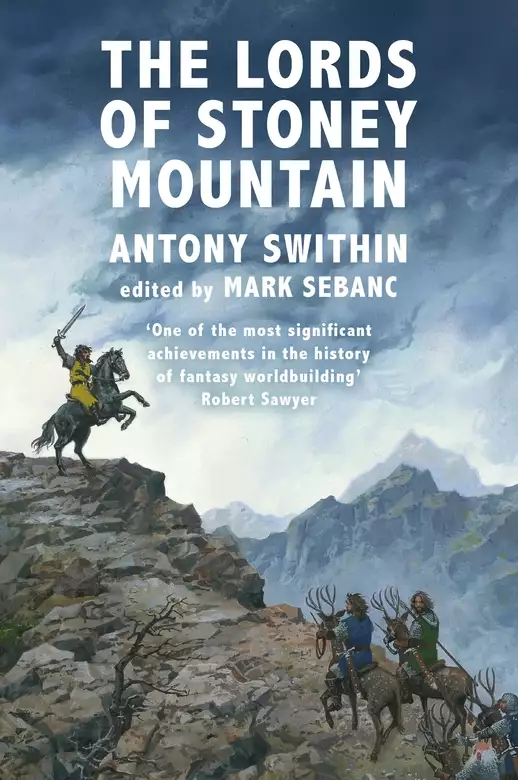

BOOK TWO OF THE PERILOUS QUEST FOR LYONESSE It is time for Simon Branthwaite to leave Sandarro, the city where he has lingered since reaching the fabled island of Roackall. Bidding a farewell to his new-found love, Princess Ilven, he sets out with Prince Avran to continue his quest for the lost realm of Lyonesse, heading toward the Stoney Mountains where many an adventure awaits them... The Lords of the Stoney Mountain is the second in Anthony Swithin's fantastical Lyonesse sequence, edited by Mark Sebanc. Find out more at https://theperilousquest.com/

Release date: June 25, 2020

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 402

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lords of the Stoney Mountains

Antony Swithin

During the fight, Rascal had wisely kept clear of me and hidden himself, but now he leapt onto my shoulder, crooning rapturously. Avran gave us a crooked smile.

‘It was well that the mist lifted, Simon. My opponent was a better swordsman than me. Your friend Dermot Fitzstephen himself, I presume?’

I had known this from the moment Dermot shouted his order to the sevdru. ‘Yes, it was, but Lednar, I’m grieved to tell you that he struck down your beast as he rode away. I hope she’s not badly injured.’

‘She’s dead,’ Lednar said quietly. ‘She was a friend of many years and I shall miss her.’

As Lednar had not looked down into the quarry, I realized immediately that it was true that a rider did indeed know immediately when his sevdru was slain. He sighed, then continued: ‘Yet we must give thanks to God that, against all odds in terms of both numbers and weapons, the three of us are not merely alive but unhurt. We owe much to Simon’s markmanship, I suspect, since only two riders reached these walls. How many did you account for, friend?’

‘Well, I brought down three,’ I said, ‘but one was not injured, for he was able to ride away.’

‘And you finished another, Lednar, while the best I could manage was to kill that unfortunate animal.’ Avran gestured at the dead sevdru. ‘I hated having to do it, but Dermot would have ridden me down otherwise. Well, let’s go out and meet our friends.’

The approaching riders, about ten or so of them, were understandably unsure of their reception, and each rode towards us sword in hand. However, as soon as they saw us, there was a chorus of joy and a swift sheathing of weapons. Their leader was burlier than Lednar, but otherwise so much like him that I recognized at once Esenar Estantesec. Seven of the others were Estantesecs as well, and there were two Derresdems in the party. I remember all their names, but there is no need to recount them.

Within minutes we were sitting on fallen blocks of stone, enjoying the sunshine and sharing a repast of dried meat, bread, and fruit. It was almost a full day since I had eaten. I was voraciously hungry, but even more welcome to me was the wine that was shared so generously all around. Nor were our sevdryen neglected. One of the Estantesecs went away to cut and bring fodder for Yerezinth and Zembelen, while another fetched them water from the spring.

Over the meal, Avran recounted our adventures, paying me tributes so excessively generous that more than once he caused my face to redden with embarrassment. There was much discussion about the identity of the grey riders, but no new suggestions were forthcoming. Afterward, we made a close examination of the bodies and accoutrements of the three who had been slain, in the hope that this might furnish useful information. It did not. The three men were personally unknown to the Sandastrians and not sufficiently distinctive in colouring or build to be of any obvious origin. They carried no papers and, apart from the rising-sun emblem stamped into their boot-tops and repeated on belt-buckles and cloak-clasps, they bore no identifying marks. Our examination of the two dead sevdreyen and their gear was no more informative, but it did furnish me with unexpected good fortune. The beast slain by my arrowshot from the wall chanced to be bearing the bundle containing my belt and weapons. Moreover, my bowstave had survived the sevdru’s fall unbroken. It was with particular relief that I took up my belt, with its array of sheathed knives, for these were virtually irreplaceable. Though one knife, of course, was lost, I managed to have twelve again, including the little Italian knife my tutor had given me originally. It was a pleasure as well to have my own sword and quiver of arrows back. My pack, however, with the good brown pelicon I had bought in Bristol, was never found.

While our investigations were in progress, the two Derresdems had ridden away, to follow and make contact with the party pursuing the grey riders. The rest of us decided to stay where we were for that night. In the bright sunshine, the old temple on its hilltop was a pleasant enough place. When evening came, there was cheerful talk and singing around a bright fire. If the temple held any ghosts, they did not trouble our sleep.

The next morning was one of sunshine and dew-sparkle, making the hills continue to seem a friendly place. It was only in mist that they took on an alien and hostile aspect. As we breakfasted, two messengers arrived from the pursuing party, bringing a captured sevdru and news.

The animal, it seemed, was one of the two whose riders I had killed, the other having been taken over by the grey rider whose sevdru had been slain. I had thought that the Estantesec party would have caught up speedily with the fleeing grey riders, but of course they also had been riding through the night. Pursuers and pursued were thus evenly matched, and the gap between them had not closed.

Just before nightfall yesterday, the grey riders had divided their ranks, two heading southeastward and two to the northeast. The Estantesec party had likewise divided, the two messengers being sent back at that point. The messengers had met the Derresdems and directed them onwards. Then they had rested for a few hours before coming to the ruins.

Their arrival, therefore, left us still uncertain as to the fate of the grey riders, but it did furnish us with a mount for Lednar. The captured sevdru was a male, as grey in hue as the riders’ cloaks. Lednar tried him and pronounced him satisfactory, but he was clearly not much enthused by his new acquisition. However, he managed well enough when, in mid-morning, we rode away. The two messengers, with two other Estantesecs, were left resting by the ruins. Later they would ride east to rejoin their colleagues.

It was a relaxed and merry ride that day. After sixteen hours of recuperation, Yerezinth was full of energy again and touchingly affectionate. With Rascal crooning and content on the pack-saddle behind me and Avran chattering happily to his cousins close or distant, I felt wholly free of the tensions that had gripped me during three frightening days. Once again, I could notice the birds, the flowers, and the little lizards among the rocks, could enjoy the sunshine and feel the pleasure of travelling through new country. I had no particular desire to talk, but I found myself humming as cheerfully as Rascal.

There was no reason now to go to Trantevar and we did not even glimpse that town. Around midday, however, we turned north and began the leisurely descent into the valley of the Dalirond. I saw many trees below us, appearing so big that I presumed they must be already close. However, though they stood ever taller before us, we seemed to take a surprising time in reaching them … Then I realized that these must be the huge trees spoken of by Avran. I recalled that he had said they grew a hundred ells high – a full three hundred and seventy-five feet. Hard to believe.

Yet, as they towered ever higher before us and loomed above us, I admitted to myself that Avran had not exaggerated. Truly these trees were giants, their very trunks as large in circumference as a church tower – and so much taller. Their bark was thick and of a creamy-brown colour, full of little holes, like the crust that forms on solidifying honey. (Later I found that it was strangely soft and yet resilient. You could hit it hard without injury to your fist and without leaving any marks). The lowest branches were high overhead and, since the great trees did not crowd one another, there was not only space, but even sunlight between them. We rode through a dappled pattern of light and shade, with plants and smaller trees crowding the sunnier spaces.

In the glades, hasedain were grazing, under the watchful eyes of herdboys whose merry whistles and cheerful greetings enlivened our passage. Twice I saw fallen trunks that had been turned into hasedain-sheds, and several times we passed hasedu-drawn carts made from hollowed-out half-trunks. In the bigger glades there were padin much like those on the flanks of Sandarro hill. However, each was built wholly from wood, each decorated by careful carpentry into elaborate geometric or natural patterns, and each painted in cheerful colours, green, scarlet, yellow, brown, or azure blue. They were the brightest and most cheerful houses that I had ever seen.

‘I like these padin,’ I observed to Avran. ‘Yours must be a happy people, to live in such habitations and to maintain them so well. Yet, if you were attacked, what would happen? Do you have any fortresses, any strong-points, in Estantegard?’

Avran laughed. ‘Why, our strong-points are all around you.’

‘The padin?’

‘No, not them. I mean the trees. Those are our defensive towers, our refuges from aggressors. There are ladders up them, tunnels in them, platforms high in their branches, lookout points at their tops. And you need to understand as well that an invader could not even use fire against us. The bark, the very wood of these trees is proof against flames. Only the lesser vegetation would burn. Our trees, our residences even, would be safe enough. It’s been many years since any enemy entered the forests of Estantevard and, believe me, they gained much in the way of pain but little profit.’

‘Why don’t you abandon your castles, then, and grow trees like this everywhere? If you did, presumably all of Sandastre would be impregnable.’

He laughed again. ‘I very much doubt that. The ingenuity of evil and ambitious men is boundless. Yet it wouldn’t work anyway. These trees, the great pevenekar, will grow only in the lands around Lake Vanadha. We’ve tried planting their seeds elsewhere. They sprout, but they never flourish. You’ll discover that their seeds are tiny and even the cones are no bigger than the end of your thumb. Odd, to think something so mighty can grow from something so very small.’

I fell to remembering my early days in Sandarro. ‘It was these forests, then, that your artists were remembering when they decorated the fifth level of your father’s castle?’

‘Yes, of course, and that’s why we Estantesecs chose to have our own rooms there. When we’re so far from our own lands, those corridors make us feel at home. Yet not all the peoples of my vard live in these forests. Some live in the hill country north of Lake Vanadha – and not even in Sandastre, but in Denniffey and Pravan. They’re venturesome people – they need to be, in those troubled lands. And they, Simon, will be very useful to us when we venture on northward.’

For some time we had been riding along a road through the big trees – but it was not a straight, cobbled track like the old Roman roads that still traversed the moors near my home, nor yet one made of cut and fitted stones like those in Sandarro and its environs. Instead, this road was made of logs hewn from lesser trees, set at the level of the surrounding forest humus and laid transversely to the line of the road itself – if one might call it a ‘line,’ for the road meandered intricately around and between the massive boles of the peveneks. If the trees were to become strong-points, a road like this would bemuse and bring many hazards to any invader. Certainly it was not designed for folk in a hurry.

Eventually the road began to swing toward the north, not in a single turn, but in a series of curves. I noticed that it was beginning to rise above the surrounding land – or, rather, that the road was maintaining its level and the land falling away. We passed through a belt of lesser trees, then into open meadowlands with many grazing hasedain, the road rising ever higher above these fields. Soon we were ascending a steep ramp leading to a broad bridge. As we traversed it, the waters of the Dalirond sparkled beneath us in the sunshine. A little scarlet, spear-billed bird, much like a kingfisher, flew upstream with the speed of an arrow.

‘Why is this bridge built so high?’ I asked. ‘Why, we must be five full ells above the water!’

It was Lednar who answered. ‘On a sunny day like this, yes, it must seem strange indeed. But picture to yourself that you are here instead on a day of storms, with pevenekar being brought down into the Dalirond by lightning or by the undermining of river banks. Such great logs, floating downstream, would sweep away any bridge of lower span – as, indeed, our ancestors found, at much cost in effort.’

‘And you must understand, Simon, that this bridge is made from the trunks of just two pevenekar,’ contributed the rumbling voice of Esenar. ‘My grandfather described to me how it was done. They built two sloping mounds of earth from either side of the Dalirond, when the river was at summer ebb. Then the trunks were tugged and heaved up till they met in mid-river and could be bound together. It took much effort, but the bridge has lasted eighty years and more already. See, we’re approaching midpoint now. That’s the line where the trunks are joined.’

Beyond the bridge and the meadowlands, the road forked into three. Accompanied by the two cousins, we took the west fork and were quickly back among the great trees again, but the other Estantesecs bade us farewell here, four going north and two east to seek homes nearby. Nor were we far from the ending of our own journey. Twenty minutes of steady jogging followed, with the big trees ever fewer and farther apart, until we found ourselves again among lesser trees. Mostly these were the slim-leaved estelens that the Estantesecs chose long ago as emblem for their vard, in modest preference to the giant peveneks. Already the estelens were in yellow bud, promising the golden glory of their spring flowering. Many sevdreyen browsed in contentment among them. Ever ready to respond to the call of their masters or mistresses as they were, they required no herd-boys to keep them from straying.

We were riding slowly upward now. Ahead was a flat-topped hillock with a group of padin set upon it – five of them – arranged in stellate pattern around a central, large structure that seemed to be a sort of hall. The arrangement was reminiscent of the plan of Sandarro Castle, but here were no stone defence-works. Instead, these wooden houses were bright with paint, sky-blue, red and gold, as cheerful as booths at a fair and about as menacing.

Avran drew his sword, tossed it high in the air, caught it by the hilt and flourished it. ‘Home at last – truly home, after so many years. Here my family lived for centuries before they became princes in Sandarro and here we’ll return when we shed the burden of ruling. Welcome to Talestant, Simon!’

As we ascended the last rise, I saw beyond the padin a steep grassy descent, a curve of brown sand, and the blue waters of a great lake – Lake Vanadha.

It happened to be the case that, though Ilven had taken me on visits to shops and inns in Sandarro, I had neither stayed in nor even entered any typical padarn – that is, one used as residence by a family. I can’t call it a house, for a padarn is more than that. Rather, it’s like a group of small connected houses, set not in a row as are so many English cottages, but in a circle around a central open space. At opposite sides are two gateways, closed at need by massive doors. Normally the outer wall is high and windowless. At the top of that wall is a steep, outwardly-sloping rampart and within this is a circular walkway extending all the way round the padarn, on which defenders may patrol at times of need. Within the walkway, a roof slopes gently inward, with regularly spaced grooves that convey rainwater down into a gutter. The rainwater then drains down into two large, covered tanks, one for humans and one for beasts, furnishing an ample supply of drinking-water for times of siege. Altogether, the padarn has a defensive design. Even the garden at centre, stocked as it is with vegetable beds, fruit-trees, and fodder-bushes for sevdreyen, is a part of that design.

The padin of the region about Lake Vanadha accord in general with that pattern, but the differences are significant. The circular walkway is bounded upon its outer side only by a fence, not by a solid rampart. Moreover, it has seats at intervals, so that its inhabitants may be at ease while enjoying the view. There are windows in the outer wall, with many little panes of thin, polished horn to admit the light and yet keep out cold winter winds. The gardens contain more flowers than feed-plants, and the padin never have gates. Of course, they are inhabited only when the land is at peace. At times of war, as Avran had told me, the Estantesecs and their neighbours take refuge in the great trees. All in all, while the padin of Sandarro are pleasant enough, those of Estantegard have a joyful lightheartedness of design that quite charmed me.

Whether in Sandarro or on the shores of Lake Vanadha, each padarn is divided into a number of units, set about the central garden like the spokes of a cartwheel. Each unit, or aspadarn, is comparable with an English town-dweller’s house of two storeys. The ground floor has a kitchen and retiring room at back beside the outer wall and a living room on the garden side, while the second floor has three or more bedrooms and is connected to the kitchen by a steep staircase or ladder. However, in sunny weather, life is largely lived in the garden, where there are tables and seats.

Most often a padarn belongs to a single large family, grandparents living in two of the aspadin, their children and grandchildren in the others. Sometimes one padarn may be shared by two or more smaller families or by a group of unmarried men or women.

In an English castle, only the nobility have private quarters and even they must spend much of their lives in the hall. A padarn, in contrast, gives a choice of communal or private activities to all that live in it.

The padarn belonging to Avran’s own family was one of the two on the lakeside. Since out of necessity the prince’s family had to reside in Sandarro, it was used only during periodic summer visits and taken care of by the families in the neighbouring padin. In midwinter, the time of our visit, it had long been closed up; nor did we intend to stay in Talestant long enough to justify its being opened for us.

Instead, we resided with Lednar and Esenar Estantesec in a padarn on the forest side of Talestant. We were welcomed by their grandparents (great-uncles and aunts of Avran and Ilven), all four of them healthy and hearty, by Esenar’s wife and six lively children, and by two other brothers and their families. Since Lednar the hunter was unmarried, it was in his aspadarn that we slept, though all our meals were taken in other aspadin.

These were cheerful, energetic, and industrious people, whom I came to like very much. Yet, in my English fashion, I considered it strange and wonderful that members of the ruling family of Sandastre should be content to live so far from that land’s capital city and so simply. When Avran told me that both great-uncles had formerly held high positions in Sandarro and that Esenar had been a quincentenar in the Sandastrian army, my sense of wonder only increased.

I was delighted to find Rokh browsing cheerfully among the estelen trees close by. He had been brought back there by cart, I learned. His broken leg had been examined and redressed by Esenar’s wife, a skilled animal doctor, and promised to heal wholly within a few weeks.

Yet, fond though I was of Rokh, I could not await the healing of his forelimb. My quest was too urgent for that. Moreover, I had Yerezinth now. Remembering my indebtedness to Lednar, I offered Rokh to the hunter. This was a transfer of ownership that delighted our friend, since the grey rider’s sevdru had proved uncongenial to him – and it was accepted readily enough by Rokh.

We stayed in Talestant for six days – six relaxing days, spent talking or singing in the garden, sauntering among the great trees (though I was given no chance to explore their ‘fortifications’), lazing on the quiet shore of Lake Vanadha, or swimming in its waters. I took the opportunity to write a long letter to Ilven, shaping my letters carefully in order to demonstrate to her how well I had profited from her tuition. Though I told her something of our doings, much of that letter inevitably became an expression of love and of longing. As it was, it made it all the more painful to think that our journey had yet barely begun. Much though I liked Talestant, I was eager to be leaving.

Avran, in contrast, was disposed to linger. He was happy to be back in the lands of his vard, of course, but, no less than myself, he was eager as well for news. We were both of us anxious to know if Dermot Fitzstephen and his three associates had been captured. If so, we were hoping Dermot could be persuaded to forsake his loyalties and name his employers. Already Avran had transmitted all the information he had gained about the grey riders to his father the Prince by way of the system of royal messengers whose swift passage binds together the bundle of vardlands that is Sandastre. It was possible that the riddle of the riders might be solved for us from Sandarro.

It was on the fourth day that we received an answer to the question of Dermot Fitzstephen’s fate and on the sixth day that messages came from Sandarro. For both pursuing parties, the trail of the grey riders had proved a long one. While we were resting in the ruined temple, the Sandastrians had continued that pursuit until the fall of night prevented any further reading of tracks. The grey riders must have rested as well and, though they were up and away earlier, their tracks were soon rediscovered. And so the hunt had resumed. It was to continue throughout much of the day on which we rode to Talestant.

By the afternoon, the gap between the pursuers and the two grey riders who had headed south-eastward was closing fast. In a gully somewhere above the lands of Indravard, they turned at bay and spurned an invitation to surrender. Instead, there had been an exchange of darts from sasayin during the course of which two of the Estantesecs were injured and one of the riders killed. Again there was a call to surrender, but the surviving grey rider ignored it. Desperately he charged his pursuers. When his sevdru was cut from under him, he fell on his own sword rather than be taken. Neither of the dead men was Dermot Fitzstephen.

It was Dermot and a companion, then, who had turned northeastward, riding so desperately fast that they were not even sighted by the other pursuing party till late afternoon on the second day. By then they were in a region of crags and broken rocks, where tracking was difficult and a passage not easy even for sevdreyen. The gap between pursuers and pursued had not closed before darkness again fell.

Next morning, the Sandastrians discovered the tracks of the grey riders’ sevdreyen only after much trouble. They followed and eventually caught up with those animals, only to discover that both were now riderless. Somewhere among the rocks, Dermot and his companion had slipped away. Though the Sandastrians alerted the surrounding vardai – Derresdavard, Kevessvard, Indravard, even Predaravard on the shore of Arcturus Bay – no trace was found of those two.

Nor did the message from Sandarro furnish any new information. It turned out that Prince Vindicon and his councillors knew nothing either of the grey riders or of any new plot against the realm of Sandastre. They were quite as puzzled as we were and even more uneasy.

The messages to Avran, then, brought him no comfort. On the other hand, a message sent to me by Ilven was an occasion for me of great contentment. Though I remember exactly what she wrote, I will not divulge her words, for they were written for my eyes alone.

So it was that, seven mornings after we had reached Talestant, Avran was persuaded to journey forth again with me. We had decided we would be wise to continue to wear soldiers’ garb, inasmuch as wandering mercenaries are common enough in the lands to which we were going. Both Zembelen and Yerezinth were joyful at being on the road once more, but Rascal, squatting atop my new pack-saddle, was sulking. I was not sure if this was out of resentment at having to leave those luscious estelen groves or on account of a growing awareness on his part that, before long, he and I must go our separate ways. (For that matter, this realization did not provoke any joy in me either.) Soon the steady jogging sent him to sleep, and, when he awoke, he was cheerful enough.

After discussions with Avran’s cousins, we had decided to ride northward into Denniffey rather than northeastward through Pravan and Volendar. Since the lands of the Estantesecs extend further into Denniffey than into Pravan, our decision was an obvious one. It made sense for us to want to remain as long as possible among people who were apt to be our friends. Elsewhere in those realms, there were indeed few places that inspired any trust.

However, there were other reasons as well. Pravan’s ruler, styled an earl, had taken to himself the powers of a petty king of the worst sort. He lived in tarnished state among servile courtiers and plundered whenever and wherever he might. The Estantesecs, with their powerful southern connections, tended to be left alone, but beyond their lands there was no safety for travellers. Volendar was equally unsafe. It was a tiny realm beyond Pravan on the edge of the plains, with a Temeculan ruling family uneasily governing a handful of Montariotan subjects who, having given up nomadic life, were perpetually under threat from their wandering kinsmen. It was most definitely not the place from which to begin a crossing of the plains and, with Antomalata and Sapandella at war close by, we would have been quite unwise to choose the northeastern route.

Denniffey was a naradat, a republic somewhat on the ancient Athenian model about which my tutor had taught me. In theory at least, the narat, its ruler, was elected on the death or resignation of his predecessor by free vote of all adult citizens. The idea was attractive, and I was disappointed to learn that practice fell far short of precept.

For almost two centuries, each successive narat had been a member of the powerful Abaletsen family. Since no other candidates had dared to stand in opposition, naturally there had been no need for elections. Yet the long rule of the Abaletsens had not been benign. Long ago Denniffey had been a rich and densely populated land, powerful enough even to rival Sandastre. However, years of almost incessant warring with adjacent realms to east, west, and south and repeated attacks from the north by Montariotan marauders had pushed Denniffey into a long decline.

Presently, however, Denniffey was at peace. Although, with neighbouring Darrinnett in fiery revolt against the Fachnese, that peace looked fragile, we trusted we might traverse Denniffey without incident and find ourselves beyond its frontiers before any new conflict flared up.

The sunshine continued through the next three days. After a few hours of riding through pasturelands beside Lake Vanadha, with brown sands at our left, where shore-birds probed for food and peeped plaintively, we crossed another high-arched bridge to enter the realm of Denniffey. This frontier was not guarded, inasmuch as both banks lay within the lands of Estantegard. Onward we rode, north up the narrow valley of the swift-flowing Demdelet, under the intermittent shade of giant pevenekar. On that night and the one following, we slept in padin as colourful as those of Talestant. The evenings were passed in song and celebration. While Avran’s rank was being discreetly ignored, he was after all an Estantesec and honoured at least as a visiting relative.

On the third morning, however, the character of the landscape began to change. The Demdelet, narrower and more turbulent now, was still at our right, but the huge pevenekar were succeeded by lesser trees, and even those became ever fewer and smaller. There were sevdreyen browsing among these trees, but always under the eye of a heavily armed guard, watchful, not for beasts of prey, but for marauding men. The padarn we slept in that night was built of stone and set high on a crag.

Our host was Senraidar Estantesec, a man of Temeculan descent in part, as his first name indicated. (Senraidar had been a name borne by many of the Earls of Stavrasard, one of whom became the first King of Temecula). He was tall, lean and wiry, with a nervous watchfulness evoked by years on the uneasy edge of the lands that fell under the sway of the Estantesecs. His wife was prematurely grey, and his children struck me as too steady and sedate for their years. However, his two sons played happily with Rascal, while his daughter seemed especially enthralled by the little vasian.

We watched the children’s games and talked in an easy, relaxed spirit till they were taken away to bed. After that, we began questioning our host about his land, for there was much we needed urgently to know.

‘Yes, indeed, there were once many people living hereabouts,’ Senraidar said, in response to an enquiry from Avran. ‘This would be a good land y

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...