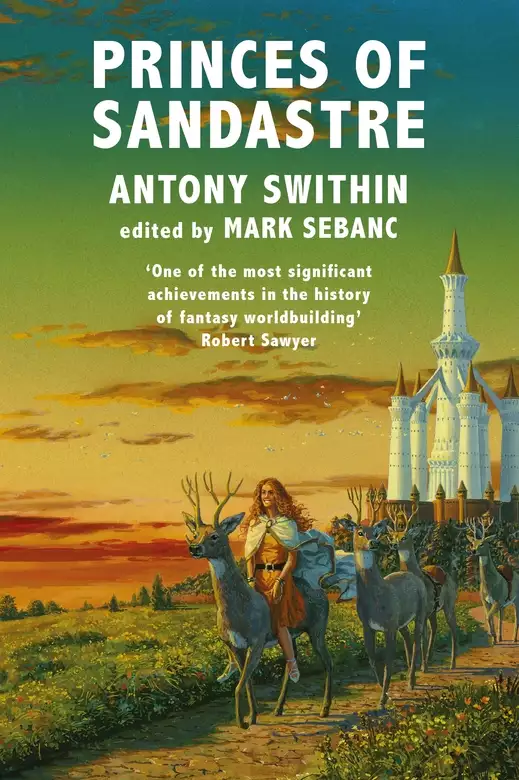

Princes of Sandastre

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

BOOK ONE OF THE PERILOUS QUEST FOR LYONESSE In the year of Our Lord 1403, as England smoulders with suppressed rebellion, young Simon Branthwaite sets sail across the Atlantic in search of the lost realm of Lyonesse. His quest will take him to Rockall, a land wreathed in legend; a land of weird beasts and wondrous happenings, of great beauties and terrible dangers. And there begin adventures stranger than the wildest of Simon's imaginings; adventures that will change the course of his life and reshape that land for ever... Princes of Sandastre is the first in Anthony Swithin's fantastical Lyonesse sequence, edited by Mark Sebanc. Find out more at https://theperilousquest.com/

Release date: June 25, 2020

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 386

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Princes of Sandastre

Antony Swithin

‘Are you ignoring me?’ It was a text message from Alexa. She was a medical illustrator, and I had been seeing her for the last half year or so.

‘No, just busy and all tied up with work. Will be in touch.’ I messaged her back, and then switched on the television.

‘And now to our CNN correspondent Dan Steele, who joins us from Castlebay, on the island of Barra in the Outer Hebrides.’

‘Search and salvage operations continue in the deep ocean waters of the North Atlantic, as ships and divers look for the wreckage of the Princess Diana. The Princess Diana disappeared mysteriously without a trace last week near the tiny island of Rockall.’

The mention of Rockall roused me from my early morning stupor. My attention drifted to the television screen, as I cradled my rather large cup of espresso, eyes now trained on the CNN correspondent.

‘So far searchers have nothing to show for their efforts except for an oaken chest filled with strange artefacts that has been dredged up from the sea floor. These artefacts have stumped the experts. Here is Professor Jonathan Morrison, expert in marine archaeology at the Smithsonian in Washington.’

‘These seem to be medallions or currency of some kind, most probably several hundred years old, but inscribed with letters that do not match any known alphabet and etched with the figures of animals that seem prehistorical, animals thought to be long extinct.’

I moved nearer the television screen, now filled with a close-up of one of the medallions. Its inscriptions and etchings danced out of the screen.

Immediately I fumbled for my phone. A voice prompted me on the other end of the line.

‘Welcome to British Airways.’

My eyes remained glued to the images playing out on the television screen.

‘I’d like to book a flight to Washington,’ I said.

Later that afternoon, the second time within a month, I was catching a flight to Dulles International. This time, unlike the last, along with my laptop bag, I brought the duffel bag with my grandfather’s manuscripts on board the plane as part of my carry-on luggage, clutching it close to me and keeping a watchful eye over it. A hefty man with distinctly unfriendly features, his hair close-cropped, plopped himself down in the seat next to me. I looked at him dubiously, glad that I had a window seat, which made things only slightly less tight and uncomfortable than they otherwise might have been.

As the plane lifted off the tarmac, I leaned back against my headrest, and my mind drifted fondly to memories of my grandfather. Born in Sheffield, he had come of age in World War II and become a seaman in the British navy. In the middle of the war, his ship was sunk by a German U-Boat in the north Atlantic. Somehow he survived and beyond all plausible explanation was found several months later drifting in a dory in those cold grey waters, clad in homespun, clutching a sealskin pouch full of papers and manuscripts.

It was the strangest and most unlikely of scenarios. The upshot was that a full half year of his life was unaccounted for. To his rescuers he explained that, when his ship had gone down, he managed to escape its sinking on one of the lifeboats, only to find himself washed up on the shores of a strange, vast land. He referred to it as Rockall, giving it the same name as that of a small speck of an islet in the north Atlantic. While he gave a detailed account of his adventures in that land, nobody believed him, even after he had returned home to England. Much as he attempted to explain the reality of what he had experienced, everybody was inclined to the opinion rather that the shock and distress of war had affected his mind. That included his wife, my grandmother. Over time he became more and more obsessed with proving he was not delusional, trying to persuade all who would listen that his experiences had been real and had occurred in an actual place, that the manuscripts he had brought with him from Rockall were not just his own mad scribblings.

Whatever it was that had happened to him changed him irrevocably. His marriage foundered, and he and my grandma separated and divorced when my dad, their only child, was in his late teens. By that time, grandpa, now an academic historian, moved to the United States to take a teaching appointment at Georgetown University, where he finished his professional career. His son, my own father, died tragically in a car accident as a relatively young man. After that, grandpa showered all his love and affection on me and my sister, visiting us often in London from America. On these occasions, he would also spend long days digging through dusty archives and manuscripts at places like the British Museum and the Royal Geographical Society, looking, as I understand it, for material related to this strange land of Rockall. I smiled to myself at the thought. I was the second person with the surname of Swithin to have approached those august institutions on this eccentric theme.

I think by that stage grandpa had grown so used to the disbelief and incredulity about his wartime experience that he was reluctant to speak about it. Still, there was at least one occasion when he opened up to me, but with an evident hesitation, as if not sure how I might react. He spoke with passion about his sojourn in Rockall and the manuscripts he had uncovered there, claiming they dated back to the Middle Ages and were related to the maternal side of his family, the Branthwaites. Then, as if realizing he had been indiscreet somehow, he spoke about the subject no more.

The plane reached cruising altitude, and I dozed off, only to be awoken with a start by the roughness and buffeting of turbulence. I glanced at my surly-looking neighbour, who regarded me askance, and then at my watch. I had slept for a good hour. I thought it better to stay awake now until I reached Washington, in order to keep my sleep cycle as little disturbed as possible and minimize jet-lag. Carefully, I reached down, opened my duffel bag, and pulled out a small leatherbound volume – my grandfather’s extraordinary handwritten account of the experience that had forever marked him as a feckless eccentric despite all the sturdy, dependable qualities he had brought to his life as an academic and as a grandparent. For a second time, I opened the slender tome. Just a couple of weeks ago, I had read it for the first time in a hotel room in Washington, but in a state of bemused distraction, the evening after my grandpa’s will was probated. Now my perspective had changed radically and I began to read it with new eyes.

I pen this account while my recollection of events remains relatively fresh, before the years take their inevitable toll of mind and memory. For all that, I expect, few eyes will read it and still fewer believe the events I recount here.

It was 1942. Fresh from reading history at Oxford, I was a 22 year old conscript in the British navy, a rating on HMS Firedrake, a destroyer with its home base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. On a grim December day, in swelling grey seas, not two weeks before Christmas, we were on convoy escort in north Atlantic waters, when we were torpedoed by a German U-Boat and gutted below the waterline. In the chaos that followed, with a growing list making the starboard side inaccessible, I scrambled to find my heavy weather gear and ran to the port side lifeboat station, where I and two other seamen managed to clamber down the life line to the last of the lowered boats, just as waves began to sweep the deck. Once in the boat, we struggled to pull away from the Firedrake. It was morning, and a mist hung heavy over the rolling seas, making it hard to see. Muffled sounds of confusion and alarm drifted to us over the water, and we took to the oars of our lifeboat in an effort to join the other boats. After a furious bout of rowing on our part, which left us breathing heavily and sweating, we realized to our dismay that we had drifted out of all earshot. We were in a daze of disorientation. Now the chill north Atlantic air and the cold spume of the sea began to bite into us. My two companions especially felt the cold, as they had not gotten the chance to gather up their winter gear. The morning fog had grown thicker, and we had no idea where our comrades and the rest of the convoy group were. We discussed what we should do next and decided that the best thing for us would be to conserve whatever energies we had remaining and let ourselves be found. We huddled together for warmth, shivering as the lifeboat rose and fell on the ocean swells, well aware that death was a very real and imminent possibility. How long we bobbed on those bitterly cold waters I don’t know. The last thing I remember is looking up into the sky and seeing a vast shimmering curtain of many-coloured lights – flaming bursts of red and yellowish green that dispelled the dank, foggy vapour. At least, I thought to myself with bitter irony, we’d have a splendid display of the aurora borealis as our funeral cortege. After that, I lost consciousness.

The next thing I knew, I was awakening from what seemed like a deep slumber in a place bathed with a clear and radiant light. My first thought was that I had crossed death’s grim threshold to whatever lay beyond the grave. I struggled to rise.

‘Stay at rest, stranger. It’s fortunate we found you, else it’s likely you’d be dead now from loss of vital heat.’ It was a soft woman’s voice. She spoke strangely quaint English with an accent I could not place. I looked up from the bed on which I lay. Hovering over me was a plump, middle-aged woman with a broad, friendly face, dressed in a cream-coloured smock with a matching wimple that seemed almost like a uniform of some kind. I looked around me and realized then I was in a large circular room with a high ceiling. Its rounded walls were inset with broad glass windows, which admitted a lavish profusion of sunlight.

‘And my comrades?’

‘Alas, it was too late for them.’

I remained silent, stunned by the bitterness of their fate.

‘But where am I?’ I asked at length.

‘Sandarro.’

‘In Britain?’ I tried to remember if there was a town by that name in the Outer Hebrides or even the Orkney Islands. Had we drifted that far in the lifeboat?

‘No, in Sandastre.’

‘Our guest must be famished.’ A male voice interrupted us, and a man emerged from a staircase that rose up through a round opening in the middle of the chamber. ‘Kertu, if you would be so kind as to fetch a tray of food, I’ll attend to him now.’ The speaker was a tall middle-aged man with salt and pepper mutton chop whiskers, dressed in droll fashion like a gentleman in an old Victorian daguerrotype.

‘Ilmarin Servessil at your service.’ He bowed gravely and extended his free hand, the other carrying a bowler hat. I met his eyes with detached bemusement, while scanning his elegant frame, wondering for a moment if he might not be part of a costume drama, elaborately staged for my benefit for reasons that quite eluded me.

‘Antony Swithin. Pleasure to meet you.’ I sat up on the cot and took his proffered hand, while the woman named Kertu slipped down the staircase.

‘No doubt you’re wondering where you are.’

‘Well, yes, I am,’ I said somewhat tentatively, trying to place his accent, regarding him and his elaborate attire now more carefully. Under his grey frock coat, he wore a claret-coloured vest over a high collar shirt set off by a puff tie of black silk fixed by a pearl tie tack, while his brushed cotton trousers tapered down to lace up black leather boots.

‘It’s as Kertu told you. You’re in Sandarro, which is the capital of Sandastre.’

‘But, with all due respect, Mr. Servessil, you speak in riddles. I’ve never heard of these places.’

‘No, you would not have.’ He smiled now. ‘Nor is it likely you would have heard of our world.’

‘Your world?’

‘Yes, our world.’

‘I still don’t follow you.’

‘You, my friend, have stepped into a new world, one that is like yours in many ways, but at the same time very different.’

‘But how? Surely, you’re jesting.’ I shook my head and pinched my arm to test my own physical reality, shaken by the vast implications of what the man was telling me, fearing now that I must be caught up in a grotesque dream so vivid and immediate in its texture that it was impossible to distinguish from real life. Or else, it crossed my mind, this was the sequel to death, one that brought with it an entry into another dimension.

‘No, you’re not dreaming, nor are you dead,’ he said, as if divining my thoughts.

‘But how?’ I repeated.

‘There is an elusive portal between our world and yours. In Sandastrian we have come to call this portal the “aseklinnot”, a word that means “little arrow slit” – a little window, so to speak. Your side of the portal is to be found in the vastness of your Atlantic Ocean near an islet you call Rockall. The name is a point of similarity between our world and yours. Rockall is also the name of our own rather large and expansive island continent.’

He paused for a moment.

‘I’ve sometimes wondered if the very likeness of names forges a connection between our world and yours. There’s much to be said about the power of words and naming. But that’s idle speculation and neither here nor there.’ He dismissed his own musing with a casual wave of the hand.

‘And that’s where I am now, on your island continent of Rockall?’

‘Indeed you are, my friend. May I call you Antony?’

‘Yes, by all means. And you?’

‘You may call me Ilmarin,’ he replied. ‘Let me explain further.’ Now he pulled a high stool to the edge of my bed and sat himself down, clutching his bowler hat. ‘It’s an exceedingly strange little window, this aseklinnot.’

‘No doubt it is,’ I said dryly. By now I was fully awake and aware and beginning to realize that I was famished – a sure sign that I had not shuffled off this mortal coil. My ravenous hunger was now becoming a distraction from the conversation, thoroughly absorbing though it was.

‘Ah, Kertu is here with your meal.’

I was a puzzled. Kertu had come back up the staircase in the centre of the room, but empty-handed, although I could detect the fragrance of warm food. She approached us and, when she reached my cot, turned her attention to the section of wall immediately behind me. I craned my neck around and noted that there was a panel set into the wall. Sliding it open, she wheeled out a dolly from what turned out to be a recessed dumbwaiter. The dolly bore a large tray laden with food, and it was placed by my bed. By now, the very smell was making my mouth water. As I swung my legs around on the cot and seated myself before my meal, I realized I was wearing a long, flowing gown much like a hospital smock. That did not stop me from tucking into a piping hot spread that included baked potatoes and a braised white meat that tasted like chicken, alongside a pleasant, tangy green vegetable unknown to me, all soaked in a delicious gravy. Never had a meal tasted better and more savoury.

‘For centuries, this window, this aseklinnot, as it is called in Sandastrian, has been thought to open up and close arbitrarily, without rhyme or reason, beyond prediction. In recent years, however, there are some basic patterns we have managed to observe. Over the long course of time, this mysterious strait that connects our worlds has at times been broad, only to close altogether at other times or become exceedingly small. Hundreds of years ago, during your so-called Middle Ages, the portal opened wider, wider than it has ever been, before or since. During this time, there was a fair degree of commerce between your world and ours, especially with the isles of Britain. And there was a good deal of settlement too. Which is why some of the nations that make up Rockall remain English-speaking and why English is one of the official languages of our Confederation. Still, I dare say you would be hard pressed after this long lapse of centuries to follow the style of speech of our English speakers here in Rockall.’

‘But what about your command of English?’I asked, as I bit into a warm slice of freshly buttered bread piled high on a plate beside my main course. ‘You speak in an older and more formal way, the way we spoke in the last century probably, during the reign of our Queen Victoria. All the same, I have no problem understanding you.’

‘It’s no accident, Antony, that it’s I who am here discussing matters with you. I go by the title of Writer to the Signet of the Ruling Council of Rockall. Mine is an ancestral, hereditary position and has been in my family for centuries. It began as the position of Scribe to the Ruling Council of Sandastre, but grew broader in its scope, when Rockall became a federation of states. It became our task as Writers to the Signet and the task of those in our employ to greet and investigate all “uldsovenei,” which in Sandastrian means quite literally “strangers from without” – strangers, that is to say, like you, who have crossed over from your world into ours. At times, it’s been a single individual like yourself who has journeyed through the gap. At other times, several individuals or whole ships have made the passage. To a point this has served us well.’

‘To a point?’ I asked.

Ilmaren held up his hand as if to stay my questions.

‘For one thing, such incursions, rare though they have been, have allowed us to make the necessary adjustments to our English diction – those of us, at least, charged with the task of dealing with the strangers who come to us from without, most of them from the English-speaking lands in your world. It has been our practice to update our skills as English speakers either by conversing at length with these stranded wayfarers or studying carefully the books they have chanced to bring. A good many of your books have made their way to us over the ages. The great writers of your language are not unknown to me.’

Ilmaren nodded to me and beamed a smile of self-congratulation.

‘For example, “There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”’

‘Shakespeare’s Hamlet,’ I mumbled in acknowledgement, my mouth full of food.

‘Very appropriate, given the threshold you have crossed, don’t you think?’

‘Highly appropriate,’ I conceded.

‘So the portal between worlds changed after the Middle Ages?’

‘Yes, indeed, over the hundreds of years that followed, in a startling reversal, the aseklinnot remained mostly closed or, when not closed, narrowed almost to the point of being non-existent. Only the occasional ship or shipwrecked seaman, like yourself, would pass through it into our waters, most often making landfall here in Sandarro, which is the capital of Sandastre and also the confederacy of states that comprise Rockall.’

‘Confederacy of states?’ I asked, as I poured myself another glass from the pitcher of hearty, malt-edged ale included with the meal.

‘Yes, we’re a federation. If you’re feeling able, Kertu has laid out clothes for you behind the screen there. They should fit you.’ He pointed to a partitioned space at the edge of the circular chamber.

‘Well and able,’ I said, feeling much of my energy and vigour had returned. I stood up from the cot, testing my legs, then made my way to the screen, on the other side of which I found a homespun shirt and black serge trousers, together with underclothes and socks and a pair of plain leather shoes. Meanwhile, Ilmaren continued with his explanation.

‘Once we were but a ragged collection of squabbling kingdoms and principalities sprawled through our vast land. Some two centuries ago, a union was forged by the energy and intelligence of one the greatest men in our history. You’ll find a monument to him up at the castle when I show it to you. He came from a distinguished Sandarrovian family and was in a direct line of descent in fact from an English wayfarer who had made his way to Sandastre in flight from one of your wars in the Middle Ages.’

‘What was his name?’ I asked, as I pulled on the trousers, which turned out to be a perfect fit.

‘You mean the founder of our union?’

I nodded.

‘His name was Lancelot Vasianavar. He was descended from an Englishman named Simon Br … Bran … Branthwaite. Forgive me. There are English words and names whose pronunciation poses a challenge to me yet.’

‘You mean his ancestor’s surname was Branthwaite?’ I perked up my ears.

‘Yes, why?’

‘My mother was a Branthwaite.’

‘Perhaps there’s a family connection. One never knows,’ said Ilmaren, rising from his stool, as I emerged from behind the screen. ‘I see that the clothes fit quite nicely. Come, have a look at our city of Sandarro spread out below us … and above us too.’

Joining Ilmarin at the window, I caught my breath at the panoramic view that unfolded before my eyes, bright in the crisp light of the raw winter sun – ridges that rose with spreading fan-like symmetry from a wide expanse of open ground that was clad in patches of snow and fronted the glistening waters of a broad harbour edged about with low towers and fortifications. On these ridges and in the hollows between stood row upon row of circular structures, their unevenly canted roofs dusted white with hoarfrost that caught the cool brilliance of the sun’s rays.

‘We’re looking south towards the Bay of Velunen over the old city of Sandarro. There’s more snow and ice than is typical. It’s been a harsher winter than usual. In any case, today’s city has long outgrown the confines of this hill, as lofty and extensive as it is. There are many more padin to be found north of our capital to the lee of these heights.’

‘Padin?’

‘Those round buildings that you see. From time immemorial, the houses we dwell in have been mostly round, and we call them padin. You are in a padarn now, as you can tell.’

‘Padarn?’

‘Padarn is our term for a single one of these padin. This padarn is one we use as an infirmary for outlanders such as yourself. Now if we make our way towards this window, you’ll be able to see something of the Castle of Sandarro. Please note, however, that it’s not a castle in quite the same way as you Englishmen conceive of castles.’

I stepped behind Ilmaren to the far end of the rounded chamber and, standing at the window, craned my neck upwards, peering into the sky above me, where a coronet of slender white towers loomed, surrounding a single elegant white spire that tapered so far into the heavens that I was hard pressed to mark it against the vast open spaces beyond.

‘More like an eagle’s eyrie,’ I said, letting out my breath. ‘From which I need to find my way home,’ I added after a pause. The soaring height of the lance-thin spire had filled me suddenly with the poignant realization of how far I was from my native surroundings, even the forced familiarity of my shipboard existence on the Firedrake.

‘That, my dear Antony, may pose a problem.’

‘What are you saying? I have to get home to England. I have a wife and infant son. Surely there is a way back? Back through that same gap by which I entered?’

‘There is, but it may not come at a time of your choosing or design. Nor soon.’

‘How do you mean, “not soon”?’

Ilmaren began walking back towards the other end of the padarn and raised his arm in gesture, pointing to the harbour and the Bay of Velunen.

‘Wayfarers from your world used to come to us from all quarters in that vast expanse of open sea to the south of Rockall. The aseklinnot was wide, easy to find and enter. There was considerable commerce between England and indeed Europe and our world.’

‘During the Middle Ages, you mean?’

‘Yes, then unaccountably the portal narrowed to the smallest of openings, an opening usually encountered by pure chance in the great reaches of the ocean – and that from your world for the most part, although I cannot be sure. It may be that some of our Mentonese traders have strayed into your realm. Every now and again a ship from your world would enter our waters, blown through this smallest of gaps by force of storm or chance. Usually these were small fishing vessels, but sometimes a man-of-war. As you can imagine, this made at times for a violent clash, but one that we easily handled by force of numbers. Still, it was disquieting whenever it happened, stirring not inconsiderable fears on our part of a larger, more significant invasion. At the same time, these turned out to be occasions for us to learn from the mechanical advances that you had made in your world and that have tended to outstrip ours by far. The most significant of these in recent times occurred some fifty years ago, when the SS Naronic, an oceangoing steam-powered ship, limped into our waters, causing us to retool our foundries and adopt coal-fired steam as a source of power. From the point of view of technics, it was a big step forward for us.’

‘And brought your fashion in clothes solidly into the 19th century,’ I said in an attempt at droll humour. ‘What about the crew of the Naronic?’

‘Most of them stayed here in Rockall and helped us adapt to the innovations they brought. You see, it was just not possible or practical to search for the aseklinnot in all that vast area of open sea, in order to make it possible for them to return home. It was like trying to find a needle in a haystack, as your English saying goes. A few, however, pined for family and friends and the life they had left behind and they would scour the ocean in their small sailing craft in their quest for this elusive port of return.’

‘What happened to them?’

‘Some disappeared, never to be heard from again. Perhaps they were able to make the journey back. Who knows? Others lived out the rest of their days in Rockall, resigning themselves, however reluctantly, to their fate. It has ever been thus with outlanders like you. By and large, there has been no return.’

‘No return?’ I felt the cold grip of fear gnawing at my gut.

‘Until now, I hasten to add, and in this regard you are indeed the fortunate beneficiary of time and circumstance. To this day, we have no idea exactly how or why this portal between our worlds is laid open, but we know more than we did. You see, in the years following the arrival of the Naronic, we were given pause to consider what might happen, if there were further commerce between your world and ours. Other strangers from without made their way to our shores and not by sea alone, as had always been the case, but rather through the air by ships that fly like birds, what you call aeroplanes. Only one or two, mind you, here and there. And besides, as is typical, there were other stranded wayfarers as well, who talked of startling new developments in your world, of great wars and weapons fearsome beyond all reckoning. We came to realize that it was only a matter of time before our world came under the perilous sway of yours.’

‘Before our technical and scientific discoveries corrupted your world, you mean?’

‘Yes, but not only that. The Ruling Council grew fearful that it might only be a matter of time before invading armies found their way through the aseklinnot. And thus, over recent years, we made a closer study of all the ocean passages south of Rockall, investigating quickly anytime a stranger appeared from without. Slowly we observed that these appearances seemed almost invariably to occur at certain times of the year. I and others pored over the historical accounts, and we were able to confirm a pattern that took its rise sometime after the close of the Middle Ages, when for some reason the thin veil that had existed between our world and yours became a heavy curtain. We were finding that most occurrences of crossover between worlds were clustered around the times of winter and summer solstice and seemed to be happening in one particular stretch of ocean.’

‘As happened with me. Near winter solstice, I mean.’

‘Yes, as indeed happened with you. Once we became aware of the pattern, we sent out ships to keep watch over that particular sea lane at these times, but with a careful awareness of the potential dangers of

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...