- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

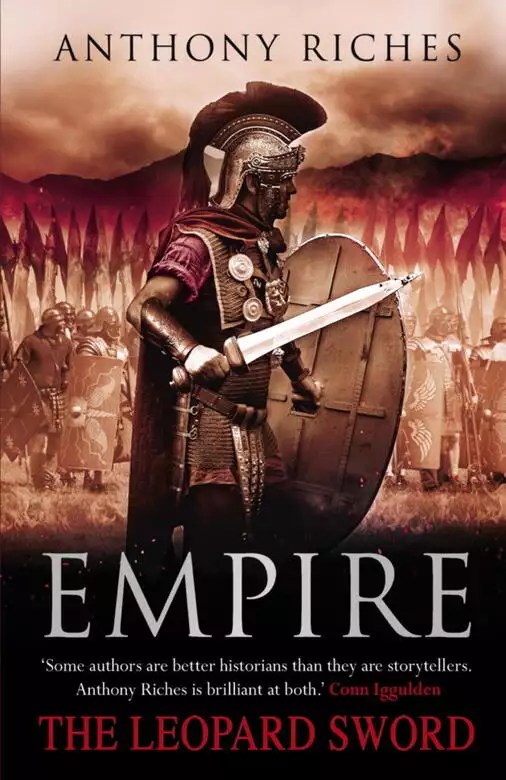

Synopsis

Britannia has been subdued - and an epic new chapter in Marcus Valerius Aquila's life begins.

The murderous Roman agents who nearly captured Marcus have been defeated by his friends. But in order to protect those very friends from the wrath of the emperor, he must leave the province which has been giving him shelter. As Marcus Tribulus Corvus, centurion of the second Tungrian auxiliary cohort, he leads his men from Hadrian's Wall to the Tungrians' original home in Germania Inferior.

There he finds a very different world from the turbulent British frontier - but one with its own dangers. Tungrorum, the centre of a once-prosperous farming province, a city already brought low by the ravages of the eastern plague that has swept through the empire, is now threatened by an outbreak of brutally violent robbery. A bandit chieftain called Obduro, his identity always hidden behind an iron cavalry helmet, is robbing and killing with impunity.

His sword - sharper, stronger and more deadly than any known to the Roman army - is the lethal symbol of his unstoppable power. And now he has moved beyond mere theft and threatens to destabilize the whole northern frontier of the empire . . .

Release date: April 26, 2012

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Leopard Sword, The: Empire IV

Anthony Riches

Apart from that I have to offer all the usual but heartfelt thanks. To Helen for encouragement and occasional strong direction (and tolerating the last touches being put to the script in the south of France); to the kids for putting up with it all; and when the pressure notched up a bit the dogs for providing the alternative perspective of lives bounded by the need to get walked and fed. My agent Robin was his usual urbane self, and Carolyn the editor sat on her hands pretending to be calm while I struggled over the line.

On the subject of Hodder & Stoughton it’s worth mentioning that my publisher remains a delight to work with, so thanks to Francine, Nick, Laure, Jaime, James, Ben and everyone else whose name I’m too scatterbrained to have remembered. Clare Parkinson did an amazing job on the copyedit and rescued me from several embarrassing errors, taking all that gore and unpleasantness in her stride. Well done. John Prigent also read the original manuscript, and made more than one telling comment, as ever!

Lastly, and as ever, thanks to everyone else that’s helped me this time round but not been mentioned. To use that old cliché it’s not you, it’s me. Those people that work alongside me will tell you how poor my memory can be, so if I’ve forgotten you then here’s a blanket apology. Where the history is right it’s because I’ve had some great help, and where it’s not it’s all my own work.

Thank you.

The Raven was the lowest grade, and would have served as doorman of the temple. St Augustine tells us that at the ritual feast he wore a raven head-mask and wings, and in the Santa Prisca murals he also wears a dark red tunic. His symbols were a caduceus and a cup, and he was under the protection of Mercury.

The Bridegroom was the second grade. He was the initiate vowed to the cult. A damaged Ostian fresco shows a bridegroom wearing a short yellow tunic with red bands and carrying a red cloth in his hands. The Santa Prisca Bridegroom, also damaged, wears a yellow veil and carries a lamp in his veiled hands. The grade was under the protection of the goddess Venus and its symbols were a lamp and a veil.

The third grade was the Soldier of Mithras, and we know a little of his initiation. The initiate had to kneel, naked and blindfolded, and was offered a crown on the point of a sword. He was crowned, but was immediately ordered to remove the object and place it on his shoulder, saying that Mithras was his divine crown. By this act he became a Soldier of Mithras and in memory of his vow he could never again receive coronation. His symbols were a quiver of arrows and a kit-bag, and he was under the protection of Mars.

These three grades comprised the lower orders of the cult.

The Lion was the first of the senior grades. Initiates are described as growling like Lions, and the Konjic relief shows one wearing a leonine head-dress. The Lion had his hands washed and his tongue anointed with honey and after this (in Mithraic ritual at least) he could not touch water, for he had entered the grade which symbolised the element of fire. The grade was under the protection of Jupiter and at least one of its duties was to attend the sacred altar-flame. Its symbols were a thunderbolt, a fire-shovel and a sistrum, or Egyptian metal rattle much used in the Mystery cults.

The fifth grade was that of the Persian, who was also purified with honey. The symbols of the grade were ears of corn and a sickle, and it was under the protection of the Moon.

The second highest grade was that of Runner of the Sun. The initiates of this grade imitated the Sun at the ritual banquet, sitting next to Mithras himself (the Father). The patron god of the grade was the Sun.

The highest grade of all was that of Father (Pater). He was Mithras’ earthly counterpart and responsible for the teaching, discipline and ordering of the congregation which he led. His symbols were a Persian cap, a patera or libation dish, a sickle-like sword and his staff of office. He was under the protection of Saturn.

If you want to know more about Mithraism I would recommend Mithras and his Temples on the Wall by Charles Daniels, one of the books I consulted in the process of researching Mithraism, and perhaps the most accessible.

By the late second century, the point at which the Empire series begins, the Imperial Roman Army had long since evolved into a stable organization with a stable modus operandi. Thirty or so legions (there’s still some debate about the 9th Legion’s fate), each with an official strength of 5,500 legionaries, formed the army’s 165,000-man heavy infantry backbone, while 360 or so auxiliary cohorts (each of them the equivalent of a 600-man infantry battalion) provided another 217,000 soldiers for the empire’s defence.

Positioned mainly in the empire’s border provinces, these forces performed two main tasks. Whilst ostensibly providing a strong means of defence against external attack, their role was just as much about maintaining Roman rule in the most challenging of the empire’s subject territories. It was no coincidence that the troublesome provinces of Britain and Dacia were deemed to require 60 and 44 auxiliary cohorts respectively, almost a quarter of the total available. It should be noted, however, that whilst their overall strategic task was the same, the terms under the two halves of the army served were quite different.

The legions, the primary Roman military unit for conducting warfare at the operational or theatre level, had been in existence since early in the Republic, hundreds of years before. They were composed mainly of close-order heavy infantry, well-drilled and highly motivated, recruited on a professional basis and, critically to an understanding of their place in Roman society, manned by soldiers who were Roman citizens. The jobless poor were thus provided with a route to both citizenship and a valuable trade, since service with the legions was as much about construction – fortresses, roads, and even major defensive works such as Hadrian’s Wall – as destruction. Vitally for the maintenance of the empire’s borders, this attractiveness of service made a large standing field army a possibility, and allowed for both the control and defence of the conquered territories.

By this point in the Britannia’s history three legions were positioned to control the restive peoples both beyond and behind the province’s borders. These were the 2nd, based in South Wales, the 20th, watching North Wales, and the 6th, positioned to the east of the Pennine range and ready to respond to any trouble on the northern frontier. Each of these legions was commanded by a legatus, an experienced man of senatorial rank deemed worthy of the responsibility and appointed by the emperor. The command structure beneath the legatus was a delicate balance, combining the requirement for training and advancing Rome’s young aristocrats for their future roles with the necessity for the legion to be led into battle by experienced and hardened officers.

Directly beneath the legatus were a half dozen or so military tribunes, one of them a young man of the senatorial class called the broad stripe tribune after the broad senatorial stripe on his tunic. This relatively inexperienced man – it would have been his first official position – acted as the legion’s second-in-command, despite being a relatively tender age when compared with the men around him. The remainder of the military tribunes were narrow stripes, men of the equestrian class who usually already had some command experience under their belts from leading an auxiliary cohort. Intriguingly, since the more experienced narrow-stripe tribunes effectively reported to the broad stripe, such a reversal of the usual military conventions around fitness for command must have made for some interesting man-management situations. The legion’s third in command was the camp prefect, an older and more experienced soldier, usually a former centurion deemed worthy of one last role in the legion’s service before retirement, usually for one year. He would by necessity have been a steady hand, operating as the voice of experience in advising the legion’s senior officers as to the realities of warfare and the management of the legion’s soldiers.

Reporting into this command structure were ten cohorts of soldiers, each one composed of a number of eighty-man centuries. Each century was a collection of ten tent parties – eight men who literally shared a tent when out in the field. Nine of the cohorts had six centuries, and an establishment strength of 480 men, whilst the prestigious first cohort, commanded by the legion’s senior centurion, was composed of five double-strength centuries and therefore fielded 800 soldiers when fully manned. This organization provided the legion with its cutting edge: 5,000 or so well-trained heavy infantrymen operating in regiment and company sized units, and led by battle-hardened officers, the legion’s centurions, men whose position was usually achieved by dint of their demonstrated leadership skills.

The rank of centurion was pretty much the peak of achievement for an ambitious soldier, commanding an eighty-man century and paid ten times as much as the men each officer commanded. Whilst the majority of centurions were promoted from the ranks, some were appointed from above as a result of patronage, or as a result of having completed their service in the Praetorian Guard, which had a shorter period of service than the legions. That these externally imposed centurions would have undergone their very own ‘sink or swim’ moment in dealing with their new colleagues is an unavoidable conclusion, for the role was one that by necessity led from the front, and as a result suffered disproportionate casualties. This makes it highly likely that any such appointee felt unlikely to make the grade in action would have received very short shrift from his brother officers.

A small but necessarily effective team reported to the centurion. The optio, literally ‘best’ or chosen man, was his second-in-command, and stood behind the century in action with a long brass-knobbed stick, literally pushing the soldiers into the fight should the need arise. This seems to have been a remarkably efficient way of managing a large body of men, given the centurion’s place alongside rather than behind his soldiers, and the optio would have been a cool head, paid twice the usual soldier’s wage and a candidate for promotion to centurion if he performed well. The century’s third-in-command was the tesserarius or watch officer, ostensibly charged with ensuring that sentries were posted and that everyone know the watch word for the day, but also likely to have been responsible for the profusion of tasks such as checking the soldiers’ weapons and equipment, ensuring the maintenance of discipline and so on, that have occupied the lives of junior non-commissioned officers throughout history in delivering a combat-effective unit to their officer. The last member of the centurion’s team was the century’s signifier, the standard-bearer, who both provided a rallying point for the soldiers and helped the centurion by transmitting marching orders to them through movements of his standard. Interestingly, he also functioned as the century’s banker, dealing with the soldiers’ financial affairs. While a soldier caught in the horror of battle might have thought twice about defending his unit’s standard, he might well also have felt a stronger attachment to the man who managed his money for him!

At the shop-floor level were the eight soldiers of the tent party who shared a leather tent and messed together, their tent and cooking gear carried on a mule when the legion was on the march. Each tent party would inevitably have established its own pecking order based upon the time-honoured factors of strength, aggression, intelligence – and the rough humour required to survive in such a harsh world. The men that came to dominate their tent parties would have been the century’s unofficial backbone, candidates for promotion to watch officer. They would also have been vital to their tent mates’ cohesion under battlefield conditions, when the relatively thin leadership team could not always exert sufficient presence to inspire the individual soldier to stand and fight amid the horrific chaos of combat.

The other element of the legion was a small 120-man detachment of cavalry, used for scouting and the carrying of messages between units. The regular army depended on auxiliary cavalry wings, drawn from those parts of the empire where horsemanship was a way of life, for their mounted combat arm. Which leads us to consider the other side of the army’s two-tier system.

The auxiliary cohorts, unlike the legions alongside which they fought, were not Roman citizens, although the completion of a twenty-five year term of service did grant both the soldier and his children citizenship. The original auxiliary cohorts had often served in their homelands, as a means of controlling the threat of large numbers of freshly-conquered barbarian warriors, but this changed after the events of the first century AD. The Batavian revolt in particular – when the 5,000-strong Batavian cohorts rebelled and destroyed two Roman legions after suffering intolerable provocation during a recruiting campaign gone wrong – was the spur for the Flavian policy for these cohorts to be posted away from their home provinces. The last thing any Roman general wanted was to find his legions facing an army equipped and trained to fight in the same way. This is why the reader will find the auxiliary cohorts described in the Empire series, true to the historical record, representing a variety of other parts of the empire, including Tungria, which is now part of modern-day Belgium.

Auxiliary infantry was equipped and organized in so close a manner to the legions that the casual observer would have been hard put to spot the differences. Often their armour would be mail, rather than plate, sometimes weapons would have minor differences, but in most respects an auxiliary cohort would be the same proposition to an enemy as a legion cohort. Indeed there are hints from history that the auxiliaries may have presented a greater challenge on the battlefield. At the battle of Mons Graupius in Scotland, Tacitus records that four cohorts of Batavians and two of Tungrians were sent in ahead of the legions and managed to defeat the enemy without requiring any significant assistance. Auxiliary cohorts were also often used on the flanks of the battle line, where reliable and well drilled troops are essential to handle attempts to outflank the army. And while the legions contained soldiers who were as much tradesmen as fighting men, the auxiliary cohorts were primarily focused on their fighting skills. By the end of the second century there were significantly more auxiliary troops serving the empire than were available from the legions, and it is clear that Hadrian’s Wall would have been invalid as a concept without the mass of infantry and mixed infantry/cavalry cohorts that were stationed along its length.

As for horsemen, the importance of the empire’s 75,000 or so auxiliary cavalrymen, capable of much faster deployment and manoeuvre than the infantry, and essential for successful scouting, fast communications and the denial of reconnaissance information to the enemy cannot be overstated. Rome simply did not produce anything like the strength in mounted troops needed to avoid being at a serious disadvantage against those nations which by their nature were cavalry-rich. As a result, as each such nation was conquered their mounted forces were swiftly incorporated into the army until, by the early first century BC, the decision was made to disband what native Roman cavalry as there was altogether, in favour of the auxiliary cavalry wings.

Named for their usual place on the battlefield, on the flanks or ‘wings’ of the line of battle, the cavalry cohorts were commanded by men of the equestrian class with prior experience as legion military tribunes, and were organized around the basic 32-man turma, or squadron. Each squadron was commanded by a decurion, a position analogous with that of the infantry centurion. This officer was assisted by a pair of junior officers: the duplicarius or double-pay, equivalent to the role of optio, and the sesquipilarius or pay-and-a-half, equal in stature to the infantry watch officer. As befitted the cavalry’s more important military role, each of these ranks was paid about 40 per cent more than the infantry equivalent.

Taken together, the legions and their auxiliary support presented a standing army of over 400,000 men by the time of the events described in the Empire series. Whilst this was sufficient to both hold down and defend the empire’s 6.5 million square kilometres for a long period of history, the strains of defending a 5,000-kilometre-long frontier, beset on all sides by hostile tribes, were also beginning to manifest themselves. The prompt move to raise three new legions undertaken by the new emperor Septimius Severus in 197 AD, in readiness for over a decade spent shoring up the empire’s crumbling borders, provides clear evidence that there were never enough legions and cohorts for such a monumental task. This is the backdrop for the Empire series, which will run from 182 AD well into the early third century, following both the empire’s and Marcus Valerius Aquila’s travails throughout this fascinatingly brutal period of history.

‘Fucking rain! Rain yesterday, rain today and rain tomorrow most likely. This bloody damp gets everywhere. My armour will be rusting again by morning.’

‘You’ll just have to get your brush out again, or that crested bastard will be up your arse like a rat up a rain pipe.’

The two sentries shared a grimace of mutual disgust at the thought of the incessant work required to keep their mail free of the pitting that would bring the disapproval of their centurion down on them. The night’s cold mist was swirling around the small fort’s watchtower, individual droplets dancing on the breeze that was moaning softly across the countryside around their outpost. The blazing torch that lit their section of the fortlet’s wall was wreathed in a ball of misty radiance that enveloped them with an eerie glow, and made it almost impossible to see further than a few paces. Shielding their eyes from the light as best they could, they watched their assigned arcs of open ground, with occasional glances into the fort below them to make sure that nobody, neither bandit nor centurion, was attempting to creep up on them.

‘I don’t mind the polishing so much as having to listen to that miserable old bastard’s constant stream of bullshit about how much harder it was in “the old days”: “When the Chauci came at us from the sea, well, that was real fighting, my lads, not that you children would recognise a fight unless you had a length of cold, sharp iron buried in your . . .”’

He fell silent, something in the darkness beneath the walls catching his attention.

‘What is it?’

He stared down into the gloom for a long moment, blinking his tired eyes before looking away and then back at the place where he could have sworn the darkness had taken momentary form.

‘Nothing. I thought I saw something move, but it was probably just a trick of the mist.’ Shaking his head, he planted his spear’s butt spike on the watchtower’s wooden planks and yawned widely. ‘I hate this time of year; the fog has a man jumping at shadows all the fucking time.’

His mate nodded, leaning out over the wall and staring down into the mist.

‘I know, sometimes you can imagine—’

His voice choked off, and after a moment’s apparent indecision he slumped forward over the parapet and vanished from view. While the other sentry goggled in amazement a hand gripped the edge of the wooden wall, hauling a black-clad figure over its lip and onto the torchlit platform; the intruder’s other hand was gripping a short spear whose blade was running with the dead sentry’s blood. The attacker’s boots shone in the light, the flickering illumination glinting off the heavy metal spikes that had carried him up the wall’s sheer wooden face. The sentry stepped forward, dimly aware of shouting from another corner of the fortlet, and raised his spear to stab at the attacker even as the other man flicked his hand as if in dismissal, sending a slender shank of cold iron to bury itself in his throat. Coughing blood, he staggered backwards and stepped out into thin air, plummeting to the hard earth ten feet below.

Lying half asleep in his small and draughty barrack, the detachment’s centurion heard the unmistakable sounds of fighting as he dozed on his bed, and he was on his feet with his sword drawn from the scabbard hanging from the room’s single wooden chair before he was fully awake. Thanking the providence that had seen him lie down without removing his boots, he pulled on his helmet and stepped out through the door with a bellowed command for his men to stand to, feeling woefully under-equipped without the reassuring weight of his armour. A shadowy figure came at him out of the darkness to his right, the attacker’s spear shining in the light of the torch fixed to the wall behind the centurion, and with a speed born of two decades of practice he swayed to allow the weapon’s thrust to hiss past him before stepping in quickly to ram the gladius deep into his anonymous assailant’s chest. Shrugging the dying man off the blade to lie gurgling out what was left of his life on the damp grass, he advanced towards the fortlet’s gate, pausing to pick up a shield left lying alongside the broken body of one of the wall sentries. A throwing knife protruded from a bloody hole in the dead man’s throat, and the centurion scowled at the ease with which his men’s defences seemed to have been compromised.

As the centurion advanced cautiously down the wall’s length, in hopes of making out the detail of what was happening around the fort’s entrance, his heart sank. The gate was already open, and a flood of attackers was pouring through it with their swords drawn. Sheltering in the palisade’s deeper shadow he watched as they overran the few men who still stood in defence of the fort, battering them brutally aside in a brief one-sided combat. Having already made the decision to slip away and report the disaster to his tribune in Tungrorum, the centurion shook his head, turning away from the sight of his command’s destruction just in time to spot a dark-clad figure coming at him out of the darkness with a short spear held ready to strike. Smashing the weapon aside with the shield, he punched hard at the reeling assailant’s face with his sword hand, catapulting the other man back against the wall. The intruder’s head hit the unyielding wood with a dull thud and he slumped slackly to the ground, his eyes glassy from the blow’s force. Kneeling to dimple the fallen attacker’s throat with the point of his gladius, the centurion hissed a question into the stunned face, the one question that had been on the lips of every soldier in the province for months.

‘Obduro? Who is Obduro?’

The dazed man simply looked up in mute refusal to reply.

‘Tell me his fucking name or I’ll stop your wind!’ Desperation lent the words a lethal menace that left the victim in little doubt as to the sincerity of this threat.

Regaining his senses, the fallen intruder cautiously shook his head, his eyes fixed on a point behind the vengeful centurion. He spoke quietly, his voice almost lost in the din of the one-sided fight: ‘More than my life’s worth.’

‘Fair enough.’

Nodding slowly, his face hardening with the realisation that they were not alone, the centurion stood, and as he turned to face the men behind him he casually pushed the sword’s point through the helpless man’s throat, putting a booted foot on his victim’s heaving chest to hold the man’s body down while he withdrew the blade with a vicious twist. Half a dozen of the fort’s attackers were standing in a loose half circle around him, all but one with spears levelled at him. Their black clothing, clearly intended to provide them with concealment in the moonless night, gave no clue as to who they might be, although more than one face seemed distantly familiar. The sixth man was armed only with a sword at his waist, but the centurion took an involuntary step back at the sight of the Roman cavalry helmet that completely hid his features. Its thick iron faceplate was tinned and highly polished, the mirror-like surface broken only by a pair of black eye holes and a slit between the thin, cruel iron lips. It reflected a distorted version of the centurion as he raised his shield to fight.

‘You wanted Obduro? Then here I am. And that was an unnecessary death, Centurion, given the fact that your men are already scattered and beaten; and he was a good man, one of my best. You know I can make you pay heavily in lingering torment for that brief moment of revenge, and yet you still chose to pay that price for a fleeting moment of satisfaction. How amusing . . .’ The words were muffled to the point of being made barely audible by the helmet’s faceplate, and the voice was distorted enough to be unrecognisable, despite the rumours as to the wearer’s identity that were the stuff of soldiers’ gossip across the entire province. ‘Tonight we are taking prisoners, Centurion, recruiting men to join us in the deep forest. You could still live, if you’ll drop the sword and shield and bend your knee to me and promise faithful service. Or you could die here, alone and uncelebrated, no matter how brave your death might be.’

The centurion shook his head, hefting the sword ready to fight.

‘Send your men at me, then, and let’s see how many I can put down before they stop me.’ He spat on the cooling corpse at his feet in an attempt to goad the masked man to a rash move. ‘I’ll cost you more than your boyfriend here before you kill me.’

The masked man shook his head in return, then drew a long sword from the scabbard at his waist in response. The blade’s surface seemed to ripple in the torchlight, its intricate pattern of dark and light bands giving it an unearthly quality.

‘I do believe you’re right, Centurion, and I’ll not waste good men when there’s no need. I’ll take you down myself.’

He bent to pick up a discarded shield before stepping forward to face the centurion, lifting the patterned sword to show his opponent the weapon’s point. They faced each other for a moment in silence before the soldier shrugged and took the offensive, stamping forward and hammering his sword into the masked man’s shield. Once, twice, the gladius rose and fell, and for a brief moment the centurion believed that he was gaining the upper hand as the other man stepped back from each blow, using his shield to absorb its force. Raising his sword again he stepped in closer, swinging the blade with all his strength. Halting his retreat, the masked man met the descending gladius with his own weapon. The two blades met with a rending screech, and in a brief shower of sparks the patterned sword sliced cleanly through the iron gladius’s blade and dropped two-thirds of its length to the ground in a flickering tumble. The centurion stared wide-eyed at the emasculated stump of blade attached to his ruined weapon’s hilt. Allowing no time for the shocked soldier to get his wits back, the masked man attacked with a pitiless ferocity. He hacked horizontally at his enemy with the seemingly irresistible sword, carving cleanly through the centurion’s shield. The layered wood and linen fell apart like a rotten barrel lid, leaving the soldier clutching the lopsided section of board in one hand and his sword’s useless remnant in the other. He threw the sword’s hilt at his opponent, clenching his fists in frustration as it bounced off the polished faceplate with a metallic clang, then hurled what was left of the shield after it, only to watch as the other man sliced the flying remains cleanly in two with a diagonal cut. Taking another step forward, the masked man dropped his shield and raised the patterned blade in a two-handed grip.

‘And now, Centurion, you can pay that price I mentioned.’

Looking at his reflection in the helmet’s polished facemask the centurion saw defeat in his own face and, enraged by the very possibili

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...