- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

AD 69: The Rhine frontier has exploded into bloody rebellion, and four centurions who once fought in the same army find themselves on opposite sides of a vicious insurrection. The rebel leader Kivilaz and his Batavi rebels have humbled the Romans in a battle they should have won. The legions must now defend their northern stronghold, the Old Camp, from the enraged tribes of Germany, knowing that they cannot be relieved until the civil war raging to the south has been resolved. Can they defend the undermanned fortress against thousands of barbarian warriors intoxicated by a charismatic priestess's vision of victory?

Release date: March 9, 2017

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 360

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

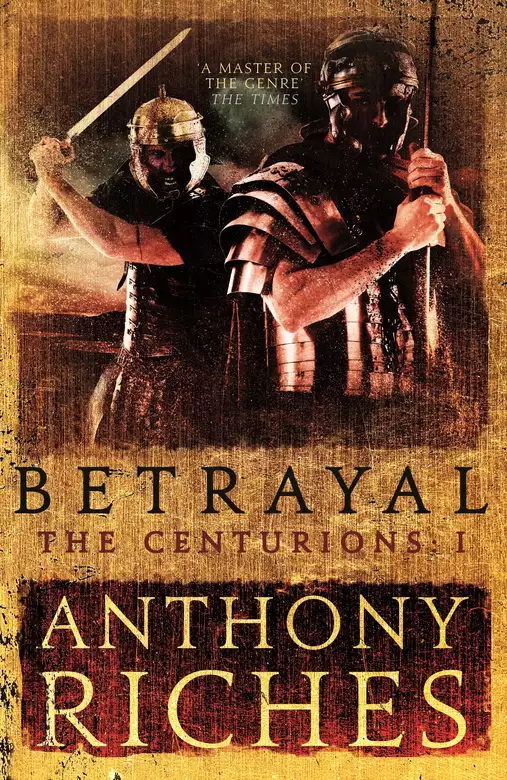

Betrayal: The Centurions I

Anthony Riches

From Nero’s perspective, however, the damage was already done. Verginius Rufus’s legionaries attempted to name their general as emperor, and, while he wisely refused to accept, Galba remained a focus of discontent in the senate. Nero committed suicide in early June, in the mistaken belief that he had been declared a public enemy by the senate. Galba, promptly declared emperor by a relieved aristocracy, began his march from Hispania to Rome to take the throne. It seemed that a relatively peaceful transfer of power had been achieved, and a disastrous civil war averted. The new emperor, a man old enough to have met Augustus as a child, was widely expected to provide some linkage with an age of strength and stability and thereby to re-establish the Pax Romana, name a suitable heir and either cede the throne or simply die at a suitable time. A new era apparently beckoned, promising the restoration of a state based on the virtues of Roman dignity and service to the empire, with an end to the excesses of the past century. But it was not to be …

‘It comes down to this then. All that hard marching from Germania Superior to the coast, coaxing the men to risk Neptune’s wrath despite their terror of the open sea, all the marching and manoeuvring since we landed …’ The speaker paused, staring down across the mist-shrouded valley, its contours delicately shaded by the faint purple light in the eastern sky behind him. ‘It all boils down to this. A river, and an army of vicious savages determined not to let us get across it.’

Gnaeus Hosidius Geta looked down from the hill’s summit at the legions waiting in the positions they had taken up along the river before dark the previous evening, almost invisible in the pre-dawn murk, then raised his gaze to stare across the river that snaked across the flood plain at the foot of the slope, and the dark mass of tribesmen on the far side, clustered around the pinprick points of light that were their smoking camp fires. Although still remarkably young for a legionary legatus at twenty-three, he was already a veteran of a successful military campaign in Africa the previous year, and had lobbied hard to join the long-awaited mission to conquer the island of Britannia despite already having done enough to earn the highest position on the cursus honorum for a man of senatorial rank, that of consul. The sole arbiter of every meaningful decision that would be made with regard to the conduct and disposition of Legio Fourteenth Gemina’s five and a half thousand men and their supporting Batavian auxiliaries, as long as he operated within the plan that had been agreed the previous evening in the general’s command tent, he clearly expected his men to see combat before the sun set on the field of battle laid out before them.

‘Indeed …’

His companion nodded, not taking his eyes off the vast army gathered on the river’s far side, the fighting strength of at least half a dozen British tribes gathered in numbers that threatened a difficult day for both Geta’s Fourteenth Legion and his own Second Augustan, unless the plan in whose formulation they had both played a leading role worked as intended. When he replied the words were uncharacteristically quiet for a usually bluff man, betraying his nervousness of the coming day.

‘Indeed. It all comes down to this. On the far side of the river there are a hundred and fifty thousand blue-faced barbarians, while on this side we have less than a third of their strength. More experienced, better armed, better disciplined and with a plan to make the best of those advantages … but what plan ever lived long beyond the moment when the first spear was thrown?’

Geta grinned at him wolfishly in the half-light.

‘Nervous, Flavius Vespasianus? You, the steadiest of all of us?’

The older man shook his head.

‘Just the musings of a man who knows his entire career turns on this day, colleague. All you’re thinking about is how soon you can get your blade wet, and how much glory you can earn in a single day’s fighting, whereas all I can see before me is the myriad ways in which I can throw this one last chance to prove myself into that river, and end up with the same feeling I had the day Caligula shoved a handful of horse shit into my toga for not keeping the streets clean. Or just end up dead. And dead might well be preferable, given Rome’s attitude to defeat. The prospect wouldn’t bother me quite so much if it didn’t also imply letting down the close friend who worked so hard to get me this position.’

The younger man laughed softly at his frown, waving a hand at the mass of Britons crowded into the land behind the river’s opposite bank.

‘Look at them, colleague. Every warrior in this desolate wasteland of a country, gathered from hundreds of miles around to oppose our march on their settlements. Some of those men haven’t seen their own lands for months, but still they’ve held firm in their opposition to our advance. Their priests have told them the stories of how we treated the tribes we defeated in Gaul, how we deal with any people that resists us. They know that if they had chosen to join us of their own free will we would have spared them the horrors that follow any battle where Rome triumphs, the slaughter, the enslavements and the despoilment of their womanhood. They know that their resistance means that everything they hold dear will be torn down when they lose, and yet still they choose to fight. Gods below, Titus, they seethe with the urge to fight us! Indeed, they might already have overrun us, if we hadn’t advanced with such care to prevent any chance of an ambush. Their chieftains know just how bloody a straight fight would be for their people, were they to turn their warriors loose to rail at our shields while we cut them to ribbons, and so they lurk behind a river they believe we cannot cross in the teeth of their spears, offering us a battle they expect not to have to fight. Look at them. Does that really look like an army readying itself for battle?’

Both men stared across the river at the British camp, a stark contrast to the ordered precision with which the four legions and their auxiliary cohorts facing them waited in their agreed start positions, close to the river. Geta pointed at the dark mass of their enemy, his voice rich with scorn.

‘They call us cowards, for not fighting man to man in their style, and yet they hide behind a narrow ditch full of water because they imagine themselves protected from our iron. Today, my friend, is the day that they will learn just how it was that we came to conquer most of the world.’

He turned to Vespasianus with a hard smile.

‘My father tried to stop me from joining this expedition. He asked me if Africa wasn’t enough victory for me, if the capture of the chief of the Mauri hadn’t already brought an adequate fresh measure of glory to our name. I just pointed to the death masks of our family’s forefathers, staring down at us from the walls and daring me to give any less for my people than they did. Given the chance, I will show this ragged collection of hunters and farmers how a Roman gentleman conducts himself when the stink of blood and death is in the air.’

He nodded at the older man.

‘And you, Flavius Vespasianus, I know that you will do the same. You may not come from an old established family, but there is iron in your blood nevertheless. You and your brother both serve the emperor with the same dedication as men with ten times your family’s history.’

‘Thank you, Hosidius Geta. That’s high praise from a man of your exalted station.’

The young aristocrat turned to find another officer standing behind them, and he dipped his head in salute at the newcomer’s rank.

‘Greetings, Flavius Sabinus. Has the legatus augusti sent you to make sure your brother and I do our duty once battle is joined?’

Sabinus, a legatus on the general’s command staff rather than a legion commander, shook his head in evident amusement.

‘Far from it. The general has every confidence in both of your abilities to enact the plan we discussed. In truth he was far keener for me to remain at his side in order to be ready for the transmission of the order to exploit your legions’ success. I persuaded him that an engagement of the sort of ferocity we’re likely to see today often places an intolerable strain on our command structure, and suggested that I should accompany your forces forward to the riverbank in case either of you should by some mischance be incapacitated. After all, it only takes one well-aimed arrow to spoil a man’s day in an instant.’

The legion commanders shared a swift glance, then Geta’s face creased in a slow smile.

‘I don’t know about your brother, Flavius Sabinus, but I have no intention of being any man’s pin cushion! The warrior who comes for my life will need to look into my eyes as he makes the attempt!’

Both brothers smiled at the younger man with genuine fondness before Flavius Vespasianus turned back to the battlefield below them.

‘My brother Sabinus has come to play the vulture, and swoop down on the feast of our success, should one of us be unlucky enough to fall in the coming battle.’

His older sibling shook his head in mock disgust.

‘Your brother Sabinus has, in point of fact, come to see Hosidius Geta’s German auxiliaries show us all just why it is that the legatus of the Fourteenth Legion is forever singing their praises. So Geta, tell me, what is it that you have in mind for your armoured savages that had you argue for them to be placed in the front line today?’

Geta nodded, looking out across the river with the hard eyes of a man who understood only too well the damage that could be done to his command were it wielded by a man without an appreciation of its strengths and weaknesses.

‘A timely question. And in answering it, allow me the liberty of asking one of my own. Tell me, Flavius Sabinus, what’s the greatest threat the Britons present to us today?’

The senior officer answered without hesitation.

‘Their chariots, that’s their greatest strength. The Britons might be one hundred and fifty thousand strong, but they’re farmers and woodsmen for the most part, some brave, some not, but very few of them as well trained or conditioned as our men. Their greatest fighting capability is concentrated in each king’s companion warriors, the bravest and the best men chosen to accompany their chieftain into battle. They number just a few hundred men, but they’ve been trained to fight from childhood; they’re well-armed and superbly motivated by their priests, and they fear dishonour in the eyes of their gods far more than death itself. Combine those men with the two hundred chariots our scouts have reported and the enemy commander has the means to deliver a pair of their best warriors with each one, as fast as a galloping horse, to any point on the battlefield where they can have the optimum impact.’

Geta nodded solemnly.

‘Exactly. Several hundred picked men descending on one point of the battlefield as fast as a charging cavalryman, delivered to the place where they can do the most damage almost as soon as that weakness becomes apparent. If a legion falters in crossing the river under the rain of their arrows, then those warriors will pounce on us like wild animals as we try to get ashore. Who knows how many men they might kill under such a circumstance, perhaps cut down an aquilifer, or even a legatus? They could blunt or even break an attempt to get across before we could put enough men on the far bank to hold it. But if we destroy those chariots …’

He waited in silence while the brothers considered his words.

‘But their chariot park is protected by the mass of their army. How can we hope to …?’

Vespasianus fell silent at the look on his colleague’s face, and after a moment Geta pointed down at the Roman forces marshalling on the river’s eastern bank in the dawn murk.

‘Your Second Legion will be crossing that river soon enough, Flavius Vespasianus, under whatever missile attack the Britons can muster, pushing across to form a bridgehead for my Fourteenth to exploit. But if we don’t do something to prevent it, then just as your leading ranks step out of the water, they’re very likely to find themselves face-to-face with a cohort strength attack from the best swordsmen they’ve ever faced, almost certainly before they’ve had the time to reform any coherent line. Unless, of course, we can destroy those men’s ability to cross the ground quickly enough to be there when your men reach the far bank. An objective in which we are assisted by the fact that they’ve tethered the horses a sufficient distance from the main force to prevent any harm coming to them in the night, given the number of hungry tribesmen there must be over there.’

Sabinus’s eyes narrowed and he stared down at the deploying legions and their auxiliary cohorts with fresh insight.

‘You’ve ordered the Batavians to attack before the Second moves forward, haven’t you?’

‘Once there’s just enough light for them to see what they’re doing, yes. You are indeed about to find out just what my armoured savages are capable of.’

‘Centurions! On me!’

With his cohorts in place as directed, drawn up in their distinctly non-standard formation in the gap between the left flank of the Ninth Legion and the right flank of the Second Augusta, Prefect Gaius Julius Draco waited. His officers converged on his position behind the first row of three centuries, each one drawn up in their usual unorthodox battle formation of three ranks of eight horsemen and sixteen soldiers, with two infantrymen standing on either side of each beast. In the normal run of things he would now have been standing out in front of his men, looking for any signs of fear or weakness, and dealing with any such manifestation in his usual robust manner, but in the pre-dawn murk he had instead positioned himself in the cover of his eight-cohort-strong command, calling his officers together where they could be safe from the risk of a sharp-eyed tribesman spotting the obvious signs of something out of the ordinary. They gathered close about him, their faces fixed in the tense expressions of men who knew that they would shortly be across the river and spilling the blood of the empire’s enemies.

‘The Romans would usually be delivering speeches at this point, boasting of their superiority to those barbarians over there …’ His officers grinned back at him, knowing from long experience what was coming. ‘Yes, the same old Draco, eh? You all know what comes next, since it’s the same thing I say before every battle. About how we don’t waste any time telling each other how superior we are to those barbarians over there, because if you strip off all this iron the Romans give us to fight in, we are those barbarians over there.’ He paused, playing a hard stare across their ranks. ‘Only more dangerous. Much more dangerous. We are the Batavi!’

He allowed a long silence to play out, just as he always did, giving time for his words to sink in and letting the growing legend of their ferocity take muscular possession of each and every one of them as it always did. Knowing that his challenge to them would take the weapon that had been wrought by their Romanisation, their appetite for war made yet more deadly by the addition of the empire’s lavish iron armour and weapons, and would rough-sharpen it back to the ragged edge that was what had attracted Rome to the Batavi and their client tribes in the first place.

‘So why do I say the same thing once again, eh?’

‘Because this will be just like every other battle we’ve fought for Rome? A bloody-handed slaughter?’

The speaker was a young man known as Gaius Julius Civilis to the Romans, but named Kivilaz within the tribe, tall, muscular and impatient in both his words and bearing, forever on the verge of fighting, or so it seemed to Draco, who viewed him with the critical eye of a man who knew he might well be looking at his successor as the tribe’s military leader. Loved by his men for his pugnacity and constant urge to compete, Kivilaz was regarded with amused tolerance by the tribe’s older officers and with wary deference by the more junior men among his peer group, who knew only too well that their apparent equality within the tribe’s military tribute to Rome was a polite fiction. Kivilaz was a tribal prince, a man whose line would have been kings with the power of demi-gods a century before, but whose members now occupied more finely nuanced positions within the tribe. Under Roman rule the men of the last king’s line were respected for their blood, and granted membership of the emperor’s extended familia, and while they possessed no more official power than any other man present, now that the tribe’s lands were governed by a magistrate appointed by vote, their effective control of that magistrate’s appointment made them almost as good as kings. Draco cocked a wry eyebrow at the younger man, echoing the smiles of his other officers.

‘I say the same thing once again, Centurion, simply because it is true. It’s time for your chance to cut off your hair, if you’ve killed for the tribe when we’ve been across that river and back.’

He waited for the good-natured laughs at the younger man’s expense to die away, one of Kivilaz’s closer friends nudging him with a grin and reaching out to tug his plaited mane, grown long and dyed red in the tribe’s traditional mark of a man yet to spill an enemy’s blood for his people.

‘So the Romans have, as usual, managed to stir up the nest until every single wasp has come out to fight. See them?’

Draco turned to gesture to the mass of tribal warriors camped on the opposite bank, their positions mainly defined by the glowing sparks of their camp fires.

‘There are enough men there to meet any attempt to cross this river and throw it back into the water broken and defeated, leaving the riverbank thick with the corpses of Rome’s legionaries, if the battle goes the way they expect. Except that isn’t going to happen. Because these Britons have no idea who it is they face. They expect no more than that which they have seen from the Romans until now: ordered ranks, tactical caution and a slow, disciplined approach once the sun is high enough to light up the battlefield. They do not, my brothers, expect the Batavi at their throats like a pack of wild dogs in the half-darkness, while most of them are still thinking of their women and stroking their pricks. In time this land will tremble at the mention of our name, but for now we are nothing to them and they do not fear us. They do not guard against us, because they do not know what we are capable of doing to them, and by the time they know that danger it will be too late.’

He looked around them.

‘We attack now, as soon as you’ve had time to ready your men. Tell them that we will cross the river in silence. No shouting, no calling of insults to the enemy, no singing of the paean. They are not to suspect our presence on their side of the water until we’re in among them. Once the first man has an enemy’s blood on his face they can make all the noise they like, but until then I’ll have the back off any man who disobeys this command. And remind them that we’re going across the river to do just one thing, but do it so well that from this day the Britons will shiver whenever they hear our name. It might be distasteful to men like us, but since it has to be done we’ll do it the way we always do, quickly and violently. Like warriors. And now, a prayer before we attack.’

He beckoned to the man waiting behind him, a senior centurion who was upstanding and erect in his bearing as he stepped forward to address them, carrying himself with the confidence of a warrior who understood both his place in the tribe and his supreme ability to deliver against his responsibilities. In the place of the usual centurion’s crest across his helmet, a black wolf’s head was tied across the iron bowl’s surface, the skin of its lips pulled back in a perpetual snarl that exposed the long yellow teeth, the mark of the tribe’s priests who fought alongside the cohort’s warriors with equal ferocity in battle and tended to their spiritual needs in addition to their military roles.

‘As your priest, my task is much the same as that of our brother Draco. Nothing that either of us can tell you now will make you better warriors, or more efficient in your harvest of our unsuspecting enemy. Draco’s role at this time is to assure you that you are the finest fighters in the empire, straining at your ropes to be released on these unsuspecting children …’ He waved a hand across the darkened river. ‘Whereas mine is to remind you that Our Lord Hercules is watching us at all times, but above all at this time, eager for our zealous sacrifice to his name. So when you kill, my brothers, kill with his name on your lips, and if today is your day to die for the tribe’s honour, then die in a blaze of glory, shouting his praise as you take as many of them with you as can be reaped by a single man. And if you are to die, then make your death a sacrifice to him, and send enough of the enemy before you to earn your welcome into his company.’

Draco nodded.

‘Wise words, which are being shared with your centuries by each of your priests even now. But remember, nobody here is to go looking for their glorious death. What I need most is live centurions for a difficult summer of fighting, not more lines in the song of the fallen, so any man I see risking his life unnecessarily will have me to deal with after the battle, if he survives.’

He waved a dismissive hand, sending them back to their centuries.

‘Enough. Go and tell your men that it is time to be Batavi once again.’

‘They’re on the move.’

Vespasianus stared down into the gloom, barely able to make out the men of the Batavian cohorts as they advanced out of the long line of legion and auxiliary forces that had formed a wall of iron along the length of the Medui’s twisting course across the battlefield. Staring across the river, he strained his ears for any cries of alarm from the men who must surely be watching the river, but the only sound that he could hear was the bellowing of centurions and their optios along the legions’ line as they chivvied their men into battle order.

‘How is it that they’re not seen?’

Geta smiled, his teeth a bright line in the near darkness.

‘Simple. The Britons do not expect an attack, and therefore they do not look for one. The fires that have kept them warm and on which they plan to cook their breakfast serve only to destroy their ability to see in the darkness. And now, colleague, watch the impossible.’

The Germans’ first cohort had reached the river’s eastern bank, and without any apparent pause had advanced into the water with their determination unhindered by the fact that it was reportedly too deep for a man’s feet to touch the bottom at that point, especially with low tide still an hour away. Vespasianus shook his head in amazement.

‘They’re swimming? In armour? Gods below, I heard the stories but I wasn’t sure I could believe them.’

‘Until now?’ Geta grinned at the brothers. ‘Believe. But that’s only half of what they can do.’

Swimming alongside the leading horse, the mount of the decurion who commanded his first century’s squadron of twenty-six horsemen, Draco looked back at the dimly illuminated scene on the riverbank behind them, nodding to himself at the speed with which each succeeding wave of men was quickly and silently entering the water. Two fully armed and armoured soldiers were swimming alongside every horse, each man using one hand to grip onto its saddle and the other to hold his spear and shield underneath him for the slight buoyancy they afforded, kicking with his legs to swim alongside the beast while the rider used its bridle to keep himself afloat. Both men and horses swam in silence, the only noise the beasts’ heavy breathing as they worked to swim with the weight of three armed men to support, filling him with the same fierce pride he felt every time the tribe practised the manoeuvre, or employed it to cross an unfordable river and turn an enemy’s flank with their deadly, unexpected presence. The far bank loomed out of the murk, and the horse beside him lurched as its hoofs touched the bottom, dragging him forward as its feet gripped the river mud. Feeling his boots sinking into the soft surface he pumped his legs furiously to keep pace with the beast, its rider now wading alongside his mount’s head as it forged forward, restraining its eagerness to be out of the water.

Releasing his hold on the saddle, he waved a hand forward at his chosen man.

‘Two hundred paces up the slope and hold,’ Draco whispered. ‘Form ranks for the advance and then wait for me. Quietly.’

Both the chosen man and decurion nodded, vanishing into the gloom while Draco turned back to the river, as his body recovered from the exertions of swimming under the dead weight of so much iron and sodden wool. He waited as the rest of the first three centuries followed the leading horses, their spacing so close that all of the seventy-odd beasts were past him in barely twenty panting breaths. The cohort’s remaining three centuries were hard on their heels, Kivilaz nodding his respect as he passed Draco at the head of his men with a look of determination that made his face almost comically grim, the cohort’s rear rank passing him with the front rank men of the second cohort close up behind them. Their senior centurion waded ashore, water pouring from his soaked clothing, saluting as he panted for breath, and Draco returned the gesture as he turned away, having passed responsibility for the river’s bank to the man whose soldiers were now surging ashore. Hurrying back up the slope, he found the front rank of his own cohort formed and ready to move, a compact mass of muscle, bone and iron with the Batavi soldiers standing alongside their horses, any uncertainty they might once have felt at the beasts’ looming physical presence long since trained out of them, just as the animals were equally well used to the presence of armoured men on either flank.

‘Any sign of life out there?’

His chosen man’s response was no louder than a whisper.

‘It’s all quiet. Want some scouts out while we form up?’

‘Yes. But quietly.’

He turned back to the river and walked down the slope past the waiting cohorts, heartened to see that his command’s incessant stream of men and beasts was almost invisible despite the slowly lightening shade of grey in the sky above them. Hurrying up the slope, they packed in close behind the leading cohorts, men squeezing water from their tunics and upending scabbards to empty them of any remaining water as they readied themselves to fight, rubbing their limbs to massage some heat back into them. The closest of them looked at Draco questioningly, eager to be on the move. Draco shook his head, his words loud enough to reach only a few of his men.

‘Not yet. But soon enough.’

A waterlogged figure squelched up to him, and Draco saluted as he recognised the tribune who had been given permission by his legatus to accompany them across the river in order to provide the army’s commanders with an account of the raid.

‘Tribune Lupercus.’

The Roman took a handful of his tunic, squeezing out the water, and looked about him.

‘Well now, Prefect Draco, are we ready to attack? The fact that you’ve allowed me across the river must mean you’ve got your entire command between my delicate body and the Britons.’

Draco grinned back at him, having warmed to the young Roman in the days since Legatus Geta had appointed him to accompany the powerful cohorts fielded by the Batavi and their allies. While the Roman was only attached to the tribe as an observer, with no formal command responsibility given that t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...