- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

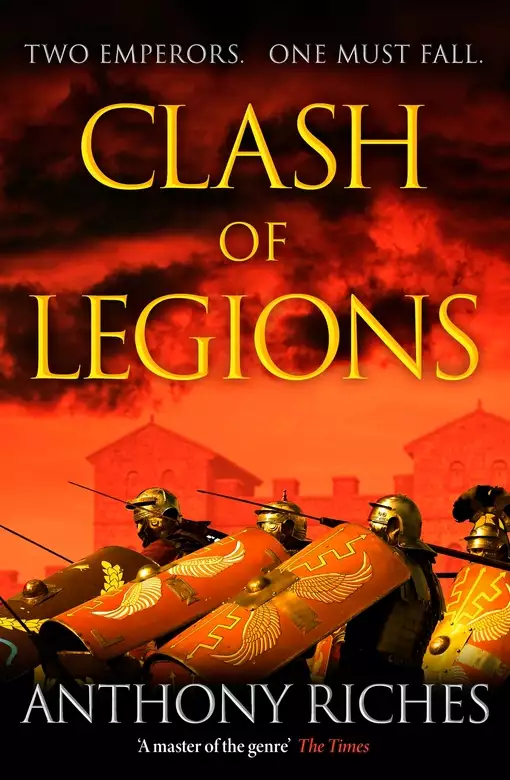

Synopsis

Two emperors - one must fall

Marcus Aquila and his patron Rutlius Scaurus have fought a superior enemy force to a standstill in Thracia, gaining the favour of the gods but paying a grievous cost in their family's blood.

Battle-weary and mourning their losses, they are tasked with rooting out a spy ring operating in the lands into which their imperial master Severus's armies are advancing.

Hunting down informers operating under the skilled and ruthless command of their sworn enemy Sartorius, spymaster to the usurper Niger, will not be easy. But the potential to turn his intelligence network, and thereby deceive and distract the enemy, might land a war-winning blow on the army of the east.

The quest to find and subvert their foes' informers will place the two friends at great risk, with torture and death the price of any mistake. While success will put them in the front rank of a bitter battle against battle hardened legions, hungry for revenge, in a bloody struggle to determine the fate of Asia's loyalty.

And Scaurus is a man with a powerful threat still hanging over him, a curse imploring the gods to fell him at the very moment of his greatest victory.

'A master of the genre' The Times

Release date: February 15, 2024

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Clash of Legions

Anthony Riches

Calchedon, Bithynia, September AD 193

‘Gentlemen!’

The assembled officers of four imperial legions turned to face the entrance to the hall in which they had been called to gather, simultaneously coming to attention and waiting for the emperor’s chief lictor to announce the arrival of their master. A heavily built former legion first spear, he and another eleven of his fellow officials accompanied the great man with great pomp and no little physicality at all times in public, carrying ceremonial axes wrapped in bundles of fasces – rods traditionally indicative of the emperor’s power – as the symbol of their duty to maintain public order in the imperial presence, and prevent any risk to the safety of the empire’s ruler. The man in question snapped to attention, a reflex from his legion days, barking a warning at the gathered officer in a tone of voice he might have hitherto used to bellow orders across parade grounds and battlefields.

‘Imperator Caesar Gaius Pescennius Niger Justus Augustus! Rome’s chosen man, and the one true ruler of the empire!’

Niger swept into the room through the doorway from an antechamber in which he had been waiting for his consilium to gather, the generals who had already gathered about his throne standing to attention as he took his seat. He had claimed imperium, for the eastern half of the empire at least, upon hearing news of the previous emperor Pertinax’s brutal assassination by the praetorians in violation of their oath to protect him, and their subsequent shockingly brazen auctioning off of the throne’s imperial power to a disappointingly inept highest bidder, Didius Julianus. The new and short-lived emperor, a hapless incompetent, had in turn been easy meat for Septimius Severus, the military strongman whose power base on the rivers Danubius and Rhenus had gifted him with sixteen legions at just the right time to take advantage of the resulting power vacuum.

Severus had been dressed in the ritual purple cloak by his soldiers almost immediately upon their receiving the news of Pertinax’s death, and had, naturally with the required modest reluctance, declared his willingness to take on the burden of imperium only at their continued insistence. With that formality out of the way, what had followed had been a swift march on Rome with all the military strength that could be spared from frontier duties, the murder of Julianus in his palace by the new emperor’s men and the straightforward strong-arming of the senate into ratifying his place on the throne under the watching eyes of his legions, whom he had marched into the city in defiance of all convention. It has been at much the same time that Niger had taken his own momentous step to claim the empire, having received the same momentous news of an imperial assassination and auction of the throne, and declared himself emperor in Antioch, the Syrian capital of everything Rome’s boots bestrode east of Byzantium.

All of which made Niger, at least for the time being, the de facto master of half of the Roman empire. Emperor of everything east of the Pontus, the sea that separated Europa from Asia, and with six legions at his back, he was a worthy contender for the throne in Rome. But even such a powerful army paled by comparison with the force possessed by his opponent. Severus had seized command of every legionary and auxiliary soldier from the lengths of both the major rivers that ran across Europa, thereby claiming everything else in the empire other than the isolated and strategically unimportant island province of Britannia, which was held by a third contender for the throne, Clodius Albinus. Which meant that Niger, as all men present knew, almost certainly lacked the military power to extend his rule to the remainder of the lands possessed by Rome, unless he was willing to gamble on the great bloodshed of a successful war fought against the odds or was blessed by greater luck than had been the case in the preceding months.

‘He looks dreadful.’

Asellius Aemilianus nodded at his neighbour’s whispered comment as he watched the master of their world take his seat on the throne that was waiting for him. Recently the former governor of Syria, Aemilianus had been the proconsul of Asia until the death of Commodus, the increasingly unhinged emperor who had ruled for thirteen years until the reputedly dubious bath-house incident that had seen the ill-starred Pertinax ascend to and briefly hold power at the beginning of the year. Aemilianus and the emperor had recently returned from the province of Thracia, where the first battle of the campaign against Severus’s army had, rumours had it, ended inauspiciously. The shadows under Niger’s eyes spoke clearly as to the pressure that he was under, in the wake of what was being described, in whispered conversations around his court, as having been much worse than the mild setback that his closest allies were attempting to call it. Aemilianus, having actually been present on the battlefield at a critical moment which had rocked Niger’s army back on its heels with its sheer and unarguably symbolic power, privately considered it to have been little better than a full-fledged disaster. He replied to the man next to him, keeping his voice equally low to avoid being overheard being in any way disloyal to their master.

‘We fought a battle at Rhaedestus, on the coast of Thracia. And certain people close to the throne’ – he tipped his head to indicate the former frumentarius Sartorius, who was standing behind the seat in question – ‘told us that it could only result in the swift and efficient destruction of a single enemy legion sent to the province by sea as Severus’s strategic gamble. He promised Niger an easy victory to blood the troops, and to get the wheels of our campaign turning. Instead of which we were forced into a bloody and attritional fight under the less-than-ideal circumstances of being forced to attack a determined and forewarned enemy.’

He shot Niger a glance, and seeing that the emperor was still composing himself and arranging his garments, ventured a little more information.

‘It ended not with the inevitable collapse of a single, outnumbered enemy legion, as had been the promise, but by an apparent intervention by the gods in support of Severus. It was beyond shocking, colleague, a blow to the gut from which he is still to recover.’

Even two weeks after the battle, Aemilianus still shuddered inwardly at the memory of the moment that had rocked both his master and his legions to the core. Added to which, Niger, as Aemilianus knew all too well, had learned of unhappy personal news, tidings of the worst possible kind with regard to his family, from the officers of the legion that had opposed them. The information that his children were held prisoner by Severus had been imparted to him in a battlefield negotiation, and only moments before the divine intervention that had forced him to allow the enemy general to leave with his men’s honour intact and their weapons unforfeited, where the minimum he had hoped for was to send them away in defeat and having sworn to take no further part in the war.

The emperor gestured to his chief strategist, the former grain officer he had promoted for the man’s known guile and cunning as demonstrated in his role as a member of the feared imperial frumentarii, and whose plan had led them to the brink of victory only for that triumph to turn to ashes in the blink of an eagle’s eye.

‘Very well, Sartorius, you say you have a plan for the next stage of this war. Let’s hope it ends more successfully than the last one did.’

The man in question bowed deeply before replying in his usual level tone.

‘As you say, Imperator . . .’

To the watching officers it seemed as if a shadow had fallen across Sartorius’s face, if only momentarily, and Aemilianus recognised the look that momentarily clouded his colleague’s expression, largely because it was founded on a set of emotions that he too was prey to in the wake of the disastrous battle. Emotions to which he suspected the emperor was equally susceptible, after such a blow to his cause. Put simply, he could see all too clearly that the former grain officer regarded what had effectively been a defeat at Rhaedestus as being much less a military setback, and far more about the gods’ apparent lack of favour for his master. Although, like Aemilianus himself, he was far too wise to say anything so likely to see him dragged away and either imprisoned as a traitor or more likely executed.

‘Gentlemen, your attention to the map, if you will.’

Sartorius took a pointer, and indicated the central point of the map of Asia and Thracia that he had had painted on the consilium chamber’s wall.

‘This, gentleman, is the strategically vital city of Byzantium, across the strait from here. It controls the Bosporus, the narrows that are the easiest place to cross the Pontus, which makes it the most likely point for an enemy army to make an entry to Asia via our province of Bithynia.’

And, Aemilianus thought, it is currently besieged by Severus’s legions from Moesia. A siege which Niger’s legions had no means of lifting given the withdrawal of the army from Thracia, to avoid the risk of their being pinned against the coast and destroyed by the superior strength of Severus’s fast-approaching army.

Sartorius continued.

‘Yes, we have chosen to withdraw across the narrows in order to deny the enemy the temporary advantage of their greater numbers, but the garrison of the city is well supplied, and its walls are thick, and deeply founded. Byzantium can and will hold in the face of an enemy siege for months, perhaps years. And while the pretender Severus is preoccupied with taking it, we will have the opportunity to regain the initiative and strike at him where he least expects it.’

Aemilianus frowned at what he suspected the former frumentarius might be about to propose.

‘You propose for us to recross the Pontus and fight in Thracia again, Sartorius?’

‘Not immediately, Legatus Augustus.’

The strategist’s tone in answering the question was respectful, Sartorius recognising the general’s strong influence over the emperor and knowing that, with his own children held hostage by Severus alongside those of Niger, the highly influential senator was a man whose world was crumbling around him, and who had little more to lose. All of which would make him a dangerous enemy in the imperial court’s scheming environment, at least in the short term. He continued in the same measured tone.

‘We plan instead to the use the time we have to regather our strength, to recruit from the local population in order to bring the legions to their full strength, and generally ready ourselves to retake the offensive. Which we will achieve either by crossing to the Thracian side of the sea – when the time is right – or simply by baiting a trap and awaiting the moment when our enemy blunders into it.’

Aemilianus nodded, recognising that, despite the failure of his previous plan, the former grain officer was right.

‘I concur. We need to see just how the usurper Severus plans to crack the nut that Byzantium represents, and rebuild our strength so that we can attack at the moment of his maximum vulnerability. But tell me, Sartorius, how exactly is it that you will know when the enemy is ready to either strike or be struck, and where they will plan to land the blow?’

The master spy pointed at the map behind him, drawing their attention to the Propontis, the sea that separated the eastern and western halves of the empire to the south-east of the Bosporus’s narrow channel.

‘Before we pushed forward into Thracia, I spent time carefully preparing a network of men who are loyal only to our master, former soldiers for the most part and with one of my former colleagues to lead them. I intended them to be the backbone of an intelligence operation, to discover our enemy’s intentions for the next steps in this war, should we find ourselves temporarily excluded from Thracia and facing the enemy across the Propontis. They are trustworthy men, dedicated to—’

‘You prepared for us to fail in Thracia?’

Sartorius turned an unreadable expression on the legion commander who had asked the question.

‘I acknowledged the potential for us to end up needing to prevent an enemy from crossing the Propontis successfully, Legatus. A potential need which I discussed with the emperor, who deemed such preparation to be prudent.’

Niger nodded, waving a dismissive hand at the senatorial officer.

‘Continue, Sartorius. I am grateful that at least one of my senior officers has exercised some forethought.’

The former frumentarius kept his face carefully composed, avoiding eye contact with the red-faced legion commander.

‘Thank you, Imperator. As I say, my informers are trustworthy men whom I have known for years, dedicated to the emperor and well rewarded for their service, and whose families are the surety of their loyalty. And now that my preparations prove to have been a wide precaution, they will enable us to place spies inside the enemy camp, military men who—’

The same legatus, irritated by his earlier put down, bridled at the spymaster’s words.

‘You have made informers of soldiers? Reduced men from a noble calling to be no better than the basest of gutter-dwelling liars?’

Sartorius raised a tired eyebrow.

‘I make informers of whoever I find is willing, colleague. And these centurions, when called to a new and challenging duty, were eager to serve their emperor in any way that they could.’ He waited for any response, but the senior officer, faced with an unrepentant Sartorius and a clearly irritated emperor behind him, nodded with a show of acceptance, and the spymaster continued. ‘They are now being sent across the narrow sea, and once they are in position they will watch and wait, feeding critical information back to us by a means that the enemy will never be able to detect, much less prevent. What information, you might ask? The answer is that it will be impossible for Severus to move his legions into Asia at the obvious point, across the Bosporus, because Byzantium dominates the narrows where such a ferry operation might be easy, making any such attempted crossing by his legions vulnerable to a sally from the city. Instead, he will have to gather a naval force to cross elsewhere, and approach the task in a more careful and calculated manner. This will give us all the time we will need to be ready and waiting, should his men attempt to come ashore on the coast of Asia before the time is right for us to retake the offensive.’

Aemilianus nodded his understanding, shooting a glance at the emperor to find him still looking sullen and preoccupied. As well he might, the general mused, were he still pondering the fateful moment in which the actions of an innocent bird of prey had taken the realities of a finely poised battle and turned them upside down. He turned to the throne, speaking respectfully but with sufficient firmness for his counsel to be both unmistakable and heard with the appropriate respect.

‘I believe that our colleague Sartorius has the right of it, Imperator. We must indeed rebuild the strength of our army, even at the risk of ceding the initiative to the usurper Severus and allowing him the next move. He has to cross the Pontus, and if he attempts to do so we will be waiting for his ships, forewarned by our spies on the other side of the sea. We will attack them even as they attempt to come ashore, sink their vessels and slaughter their men in the surf as they struggle to fight their way onto dry land! And with the usurper’s claws pulled out, we will be able to go back on the offensive in Thracia, and rid the empire of the dangers of his false imperium for good!’

Niger stirred on his throne, raising his gaze to meet his most senior general’s eyes and speaking in a near whisper that bespoke the horror of what he had learned from the enemy officers on the battlefield at Rhaedestus, when they had paused the fighting to negotiate the terms of an expected surrender that had never come to pass.

‘He has our children, colleague. He has my children!’

Aemilianus nodded soberly, walking closer to the emperor in order to whisper in his ear.

‘Indeed, he does, Imperator. And if that sad truth is enough to kick the legs out from under your reign, then I am bound to suggest that you would be as well to admit it to yourself, and to the rest of us, so that we might at least attempt to make our peace with Severus, rather than further antagonise him with continued resistance.’ He stared levelly back into the other man’s outrage, as the emperor swivelled his head to glare at him, speaking again before Niger’s rage could boil over. ‘And if that makes you want to have me executed, you have only to give the command and I will fall on my sword, here and now. If we lose this war then there can be no doubt that Severus will have me killed, if only to punish my disrespect in initially indicating that I might side with him before I eventually took my current position at your side. Either way I am a dead man, either at that time or here and now, but were I to take my own life he might just decide to spare my children, deeming them as being of no threat to him, since he will not have had to order my execution.’

Niger thought for a moment before making any response, visibly swallowing his anger as the reality of his general’s predicament sank in. At length he spoke, pitching his voice to be heard by all in the room.

‘My trusted and esteemed adviser Asellius Aemilianus makes an excellent point, gentlemen. We are committed to the path on which we have started out, no matter what obstacles we encounter or personal sacrifices we have to make. And so we must strive to our utmost in order to overcome this latest setback, and we will fight on in the knowledge that we can only be on the right side of events when the histories are written.’

He stood, putting a hand on the hilt of his sword for martial effect.

‘I command you all to go about the task of bringing our army to the maximum possible strength. Recruit, resupply and train our legions, and make our men ready to stand toe to toe with Severus’s army when they attempt to sully the shores of Asia with their boots. And you, Sartorius . . .’

The master spy turned to his emperor with an expectant expression.

‘Imperator?’

‘You failed to bring me victory at Rhaedestus largely as the result of the acts of one man.’

‘That man being Gaius Rutilius Scaurus, Imperator?’

Niger grimaced at the memory of the hard-faced tribune’s imperturbability when they had met on the battlefield, on blood-soaked ground stamped into ruin by the boots of the combatants and surrounded by the dead and dying men of both sides. His face hardened at the memory of Scaurus’s absolute refusal to grant him the prize of his legion’s surrender, an outcome that had seemed so inevitable at the start of the battle, and thereby buying time for the random act of a passing eagle to shatter Niger’s legions’ morale simply by dint of its random but heart-stopping choice of perch.

‘Yes. Scaurus. Lucius Fabius Cilo would never have trained that legion of his to anything like the perfection of the men we faced, or positioned them as well or even inspired them to fight in so bestial a manner and for so long, without that young bastard’s assistance. I curse the day that I met him in Dacia all those years ago. So, among your other preparations to disrupt our enemy’s preparations to invade our provinces, you are to make sure that you find and capture Scaurus, and the equestrian Aquila who fights at his side. I want them both to be dealt with once and forever, and in as protracted and painful manner as possible. Let them learn just how unwise it is for any man to stand in the way of an emperor!’

1

Marching camp of the army of Septimius Severus, Roman province of Thracia, September AD 193

‘Fourth Legion, halt!’

The first cohort in the column of marching men came to a slightly untidy stop, the rapping of the hobnails that remained on their badly worn boots dying away with a jumbled staccato rattle, rather than the precise massed stamp of what in a time of peace would have been hundreds of right feet. But then to be fair to the legion, Marcus Valerius Aquila mused, shooting his friend Dubnus, the Fourth’s first spear a sympathetic glance, there were a good deal fewer than the usual five thousand men marching behind their eagle. Even more of a mitigation for such a poor showing of the expected military discipline was the fact that a good third of those who had survived the battle they had fought a fortnight before were still carrying wounds and injuries, disabilities that were likely to see them discharged from the service before their twenty-five years were fully served.

The Briton Dubnus, a heavily built bear of a centurion only recently promoted to legion first spear, after the death of the man under whom he had served for fifteen years, looked equally unlikely to seek out any miscreants to blame for his men’s evident lack of polish. He turned and looked down the legion’s sadly reduced line, as each successive cohort stopped marching in a similar display of exhaustion, a look of sadness crossing his face at the sight of so many men holding their tent-mates upright. Raising his voice to a parade ground roar he shouted a command at his brother officers standing at the head of each cohort.

‘Stand at ease! If you need to fall out, do so with some decorum! Let’s show these barrack room flowers what a legion that’s seen off three times its strength is worth!’

The big man turned back to face the centurion of the guard who had walked out of the massive camp’s eastern gate while he had been speaking, tilting his head back to look down his nose at the man in a way that Marcus knew often presaged trouble for the stare’s unwitting recipient.

‘You’re the Fourth Legion, right?’

Marcus stepped forward, his fellow tribune Vibius Varus at his shoulder, the two men’s rank evident in their bronze armour and gilded helmets, and pointedly waited for the centurion to salute him before replying.

‘Yes, we are, Centurion. The Lucky Flavian Fourth, returned from battle victorious and in need of some rest and recuperation. Did you receive our message advising of our arrival, and advising that tents and food would be needed, and the necessary medical aid for five hundred wounded men be ready?’

The other man nodded, with the look of a man trying to work out how to best show obsequious respect to a superior he was about to disappoint.

‘Yes Tribune, your camp is ready and waiting.’

‘Very well, you may lead us to it. And while you’re doing that, you can also send a runner to the medics and remind them about the message we sent ahead of us, and that we have at least five hundred men who will require their attentions.’

‘Yes Tribune.’

The Fourth’s legionaries straggled into the camp’s sea of leather tents under the hard eyes of the men already encamped on either side of the Via Praetoria. The men watching them progress past their well-ordered sections of the marching camp were legionaries who had marched east from Rome and were yet to see battle, whereas the battered troops limping past them had been transported by sea to play the part of a regrettable but strategically necessary sacrifice. Marcus tapped the centurion on the arm, gesturing to the weary, hungry and wounded men straggling past them.

‘Let me tell you, Centurion, how it is that my legion came to be in what I’m sure you’ve already decided is a “shit state”. We were selected to disrupt the enemy army’s preparations for war, by the device of our arriving unexpectedly in their rear by sea, with orders to attack them out of the blue and cause as much disruption as we could. Our legion was loaded onto a praetorian fleet in Misenum, near Vesuvius, and shipped all the way here as fast as an arrow from a bow by comparison with your leisurely march, then dropped off on a beach with orders no more detailed than to go and find the enemy. It was a plan that was always likely to end up with us fighting a desperate battle against overwhelming odds, and in fact it brought three of the enemy’s legions down on us like wasps onto spilt honey. Three legions to our one, Centurion.’

The officer had the good grace to look embarrassed, but Marcus was already continuing.

‘It was a strategic masterstroke by the emperor, of course, to disrupt their preparations so rudely, but you can probably guess the predictably heavy price that we paid to delay Niger’s plans. We were only ever expected to suffer a bloody defeat, you see, a loss from which an honourable return, without our being forced to swear an oath to take no further part in the war, was probably considered an impossibility – albeit one we would be punished for, of course. But we didn’t lose, and we weren’t humiliated. We made Niger’s legions swallow that humiliation instead. These men staggering into your well-organised camp, wounded and hungry, they were the victors, the heroes of a battle they had no right to win. And now, when we expect to receive some respect in return, I’m not really getting the feeling that there’s any on offer.’

The centurion, clearly embarrassed, remained silent, and Marcus and Dubnus exchanged glances as they were led further through the temporary fortress. The Briton’s look of puzzlement hardened as they approached the western gate and marched back out into open ground, where a line of carts loaded with leather tents awaited them.

‘Here? We’re expected to camp here?’

The officer of the watch had the good grace to look embarrassed at Marcus’s question.

‘Yes Tribune.’

‘Men who took on three legions and emerged victorious are expected to camp outside the walls? As distant from the camp hospital, the supply tents and the river as it is possible to be, and yet in most need of all three? Is this some kind of joke?’

‘I was ordered to—’

‘It’s all right, Centurion, we understand perfectly well what’s happening here.’

The hapless officer came to attention again as two more officers approached from further down the column, realising from the finely tooled bronze armour and white linen cloak worn by the older of them that he was in the presence of the Fourth Legion’s commander.

‘Legatus sir, as I was telling your officers, the order for you to be placed here—’

Legatus Cilo raised a hand to silence him, sharing a look of dark amusement with the equally splendidly equipped younger man beside him before answering.

‘We were half-expecting something of the sort, Centurion, and it really isn’t important. You could go and enquire of the hospital when the medics will be making an appearance though? And intimate to the chief medicus that if I lose any of the men who have lived until now from the lack of care, then he will have made a powerful and dangerous enemy of a man who is likely to be commanding a good deal more imperial favour than you people might be expecting. Dismissed.’

‘Sir! We will do what is ordered, and at every command we will be ready!’

The officer gratefully hurried away from their ire just as another, older officer came out of the camp gate and made his way over to them, saluting Cilo in a perfunctory manner and looking about him with a cold stare that told the newcomers exactly who it was that had made the decision to place their tents in such an ignominious position.

‘Are you gentlemen the officers of the Fourth Legion?’

Cilo looked him up and down for a moment before responding, gesturing to his officers.

‘Yes, we are. I am Lucius Fabius Cilo, and these are my tribunes, Rutilius Scaurus, Vibius Varus and Valerius Aquila. And you, I presume, are the camp prefect.’

‘Indeed I am, serving under Legatus Augustus Laetus, and I bid you welcome to my camp, gentlemen. We—’

Scaurus, having shot a glance at Cilo and received a nod of encouragement, overrode the official with the ease of long-practised social superiority.

‘Are we to presume that your appearance here so soon after our arrival is solely intended to allow you t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...