- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

AD 1215: The year of Magna Carta—and Robin Hood's greatest battle.

The yoke of tyranny King John is scheming to reclaim his ancestral lands in Europe, raising the money for new armies by bleeding dry peasants and nobles alike, not least the Earl of Locksley—the former outlaw Robin Hood—and his loyal man Sir Alan Dale.

As rebellion brews across the country and Robin Hood and his men are dragged into the war against the French in Flanders, a plan is hatched that will bring the former outlaws and their families to the brink of catastrophe—a plan to kill the King.

The roar of revolution England explodes into bloody civil war and Alan and Robin must decide who to trust—and who to slaughter. And while Magna Carta might be the answer their prayers for peace, first they will have to force the King to submit to the will of his people....

Release date: June 18, 2015

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

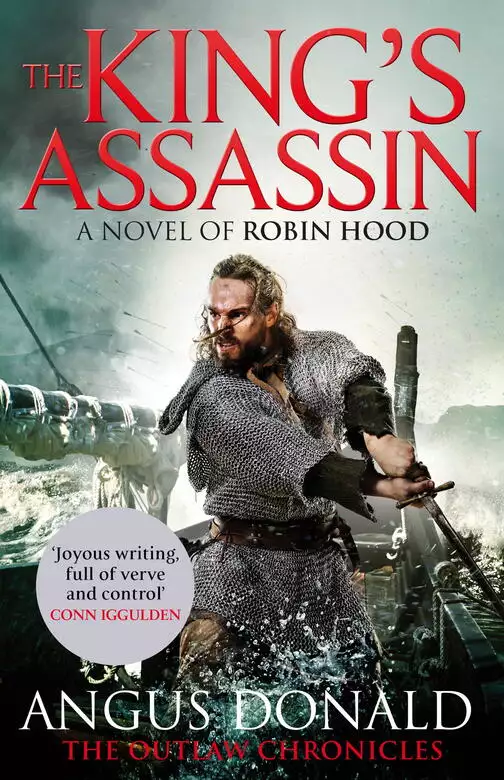

The King's Assassin

Angus Donald

And neither were we alone. On either side of the vessel as far as the eye could see were hundreds of ships like ours: long, low, lean, single-masted vessels crammed with fighting men, weapons, shields, food and stores, as well as bigger craft – galleys and busses, cogs and even a river sailing barge or two making the perilous crossing to the low lands across the German Sea from England. There were nearly five hundred vessels in all, I had been told, and some seven hundred knights, as well as many hundreds more men-at-arms, archers, crossbowmen, servants and squires – even a few women, hardy young trulls and big matrons with forearms like farriers, who followed a host wherever it went and provided the services that fighting men always require: cooked food, clean clothes and a willing body to warm the blankets.

We were a sea-borne army. An armada. And we were going into battle.

I was in fear. I must admit it: indeed, I was terrified. This was not my first time going into the storm of battle, nor yet my twentieth, but the fear had come down on me that bright morning like a vile fog, like an invisible plague drawn inside me with my breath that was now eating away at my guts, gnawing away the strength of my bones. I was convinced that I would be butchered in the coming conflict. I could clearly see the sword cut that would smash through my guard, cut through helm and arming cap and crush my skull; I could feel the prick of the spear as it thrust into my chest, bursting apart ribs, crushing my organs. I could taste the searing pain, the gush of blood, the weakness and wrongness of it all, and the cold, slow, slide into black.

I shook my head, trying to banish these visions of bloody disaster. I was a brave man, I told myself: be brave. But I had never had it as bad as this, never, not in all my long years of soldiering. I had fought many times, I’d won and lost, I’d been wounded and captured, I’d been tortured and condemned to certain death: but I had never felt as plain, ordinary, brown-your-braies frightened as I did that bright May morning off the coast of Flanders as we approached the estuary of the Zwin river and the port of Damme in the year of Our Lord twelve hundred and thirteen.

It must be my age, I thought. For I was no callow lad, I was a seasoned man-at-arms of eight and thirty summers, wise in war and versed in the ways of men – a knight, indeed, with a manor to my name, a dozen fine scars and the beginnings of a belly – not some green sprig going into his first skirmish. I had called upon St Michael, my personal protecting angel, in half a hundred fights, and he had almost always warded me with his long white wings. But where was he this sunny morning? Where was my holy guardian that day as the wind swept us remorselessly across the flat blue sea towards our enemies, the mighty legions of Philip Augustus, the King of France? My spine ached, my belly felt cold and sickly, my left hand trembled, and I had to make a fist to mask the shameful physical manifestation of my cowardice.

I looked to my left at the nearest snake boat, some thirty yards northwards, and took a little comfort in the sight of a huge red-faced man with fat blond plaits on either cheek standing by the mast, one massive arm curled around it. He looked invincible. He wore a knee-length mail hauberk that seemed a little too tight across his vast chest, leather boots and gauntlets reinforced with strips of iron, a long dagger hung horizontally at his waist and a gleaming double-headed axe rested on one brawny shoulder. He saw me looking and cupped a hand to his mouth.

‘We’ll soon be amongst them, Alan, don’t you worry,’ shouted Little John, his words reaching me easily from the neighbouring ship over the howl of wind and sea. ‘It’s going to be a rare brawl,’ he bellowed. ‘Nice and bloody, you mark my words!’

I wrenched up a suitably carefree grin, as befits a man of war, and waved cheerily at him – but my guts were churning and I had to look away from his honest red face. How did John do it, in battle after battle, how did he find such joy in death? He had taken appalling wounds in his time; he had felt the Devil’s stinking breath on the back of his neck. How could he still see this bloody business as a jolly game?

In that brief moment, I hated my old and trusted friend. I wanted to see him humbled; laid as low as I by fear and weakness. Immediately, I chided myself for that ignoble thought. John was John, and in the mêlée I knew he would take a sword blow meant for me – just as I would for him. If only I could master my fear. I glanced behind me and my eye alighted on a youth who was going into his first battle. It must be ten times worse for him, I thought, as he knew not what to expect. But, if he was as afeared as me, he was doing a far better job than I was in concealing it.

He was a handsome lad of eighteen or so, with light-brown hair and a long, lean face. He was dressed in an expensive hauberk of the finest mail and a domed helmet with golden crosses incised into the steel. His weapons, too, long-sword and dagger, were of the finest quality. And his shield bore the fierce depiction of a snarling wolf in gold on an azure field. But it was his face that made me pause every time I looked into it. But for his eyes, which were a rich dark blue, he was the spitting image of his father Robert Odo, Earl of Locksley, the man who was my own lord and master and who had persuaded me to undertake this very voyage into battle.

Miles Odo looked entirely unconcerned about facing mortal combat for the first time. True, he had been trained by some of the best swordsmen and masters-at-arms in Europe, former Knights Templar for the most part, since he was old enough to lift a sword tip off the ground. But, as far as I knew, he had never faced an opponent who was genuinely seeking to kill or maim him; nor had he ever faced a storm of arrows and crossbow bolts that plucked away the lives of the comrades all around you at the whim of Chance. A half-smile adorned his smooth young face, his brow was unwrinkled, though a dimple crinkled his cheek when he saw me watching him; he looked like a carefree young blade on a pleasure cruise – in pursuit of wine and women, not pain and slaughter – and by that placid cast of face I knew that he was as petrified as I was, or perhaps even more so. For he wore exactly the same expression his father had always donned when things were at their worst.

Robin’s nonchalant words to me at the quayside at Dover, before we parted and he made his way to his own ship, echoed in my ears: ‘Keep an eye on Miles, will you, Alan. Marie-Anne would be most upset if anything were to go amiss…’

It might have sounded as if Robin was unconcerned about the safety of his second son. But I knew him better than that. He had been commending Miles into my care, asking without asking that I watch over him like a mother hen in the coming storm of steel. And I would, fear or no fear. For the debts of honour I owed to Robin, and the love I bore for him, were bigger than all the terrors of the world. We had fought together on more than a dozen battlefields from the Holy Land to the fields outside his home castle of Kirkton in Yorkshire. He had saved my hide so many times I could not count them. I would look out for his younger son as if he were my own.

Miles’s elder brother Hugh, who was Robin’s heir to the Locksley lands, was in the lead ship, a proud high-ended cog, with his father and William Longsword, the Earl of Salisbury, the leader of this seaborne expedition.

Hugh was a very different man to Miles. Where Miles was tall, fair and willowy, Hugh was shorter, dark and strongly built. While Miles was whimsical, dreamy and prone to laziness, though a dazzling fighter with sword or dagger; Hugh was studious and level-headed, a talented horseman and a dogged if unimaginative swordsman. Although they were separated in age by four years, they were very close, devoted to each other, and to insult or injure one was to bring down the wrath of the other.

I swung my legs over the bench so that I was facing back down the ship and face to face with Miles.

‘Here, lad,’ I said proffering the hilt of Fidelity. ‘See if your young fingers can fix this loose bit of silver wire. Can you tuck it under there, under that loop…’

Miles bent his head over the weapon for a few moments, his nimble fingers tucking and tugging. The ship’s captain altered course slightly, the sail cracked like a breaking branch, a rogue wave slapped the ship’s side and a salty packet of water leapt up and dashed itself against the shield on my back and over my neck, sending freezing trickles down my back under my iron mail. I tried not to shiver.

‘It is a truly wonderful sword, Sir Alan,’ said the lad, handing it back to me, the loose end of wire neatly out of sight. He was right: a blue sapphire set into a ring of silver made the pommel, the long silver wire-wrapped grip allowed it to be wielded with one hand or two, the cross-guard was thick squared steel ending in two sharp points, which I used as a weapon almost as much as the yard-long shining steel blade.

‘It’s certainly an old one,’ I said. ‘I killed an evil man for it before you were born. But it has served me well over the years. Very well.’

There was a silence between us, as we both admired the play of light on the naked steel. Then the young man cleared his throat a little unnaturally.

‘Sir Alan,’ he said, ‘is it true what Father says about you, that you have killed many, many men?’

I squinted at him in the bright sunlight, shrugged and said nothing.

He had the grace to colour at this gaucherie.

‘I mean no disrespect, Sir Alan,’ he said. ‘Nor do I mean to pry into your affairs. I merely wanted to ask … I just wondered what it feels like, you know, to kill a man. To take everything he has – and will ever have.’

I thought for a moment. Facing battle, he deserved to hear the truth.

‘It is hard,’ I said truthfully. ‘It is very hard the first time.’ My mind went back to a woodland glade in England more than two dozen years earlier, and a dead knight on the ground by my feet, a boy not much older than I was then, with his neck broken by my blade. ‘It feels wrong,’ I said. ‘Like the worst sin imaginable. But it does get easier each time you do it. Much easier. Then it becomes no more than something that you have to do, a task, a labour, something that must be accomplished.’

He looked me straight in the eyes, his deep-blue eyes in his father’s face.

I said: ‘There will be killing aplenty today, lad, and we will do our part. But I want to ask a favour of you, a boon, if you will. When we go in, I want you as my shield-man. Will you do that for me? Sir Thomas Blood will be on my right, as usual,’ I nodded over to the far side of the boat where a short, dark-eyed warrior in full mail was putting a final edge on his sword with a whetstone. ‘But I want you on my left. In the thick of battle, I want to know I’ve got a good man on my shield-side. Will you do that for me? Stick by me; guard my flank?’

Miles nodded and gave me a beautiful, beaming smile. ‘I am deeply honoured, Sir Alan. You can rely on me. To the death!’

I nodded and swung my legs back over the bench to face forward again. I wondered how soon he would realise that the ‘favour’ I had asked of him – that he stay close by me on my left-hand side – was in fact no more than a ruse to ensure that he was under the protection of my shield in the coming fight.

And I wondered what he would say when he did find out.

No matter. There was grim work ahead and no time for niceties. And I would not be able to look Robin in the eye – or Marie-Anne – if their son was killed under my protection. I’d see him safely through this blood-bath or die trying.

The land had jumped a little closer and I stood up from the bench and looked out under a hand. There were sandbars visible, patches of lighter blue amid the turquoise, and I felt the snake boat shift direction slightly as the captain, a dour man called Harold, guided our vessels between two of the larger ones. But I could also make out the spindly masts of ships ahead by the smear of coast. Many, many ships spread right across the wide mouth of the estuary, with more concentrated at the centre where the river debouched brown from the muddy flatlands. As we came closer, I could make out the masts and rigging of hundreds, no, maybe more than a thousand ships, seemingly stacked against each other. In the late afternoon sun they looked like a great tangled forest in winter, the trunks and limbs bare of their leaves. My God, I thought, this is the whole enemy invasion fleet. Right here. All of it. King Philip’s whole force is spread out before us, riding at anchor, or drawn up and beached on the sandy shore as carelessly as if they were in the port of Harfleur.

Our lead ship, a big cog with a high castle-like fighting platform at each end, and which flew the lions of England from the mast, was signalling to the fleet. I though I could make out Robin on the deck of the vessel with his back to me, conversing with a knight in glittering mail. Robin’s long green cloak fluttered behind him in the north-westerly breeze. He was pointing upwards to where coloured pennants, tiny at a distance, were being hauled up the mast. A hundred yards behind the lead ship, I followed the line of his pointing finger, and could easily make out the message the flags revealed. We knew our orders, we’d been thoroughly drilled in the flag codes and, as they fluttered cheerfully in the salt-tanged air, their daunting instructions were startlingly clear.

I turned back to the body of the snake boat and addressed the score of men-at-arms sitting eagerly on the benches – men in mail and leather, bowmen, spearmen, swordsmen, helmeted and helmless – and said: ‘It seems, lads, that we are not going to waste any time. No scouting, no hesitation, no parley. We go straight into the attack this afternoon. We are going in to take, burn or sink any French ships that we can. Lace up, men, and draw steel. Battle is upon us. May God Almighty go with us!’

I fumbled for my gauntlets, which were tucked into my belt, and in doing so I looked down at my naked left hand. The shaking had completely stopped.

My hand was as steady as a stone.

As I pulled on my stiff gauntlets, reinforced with fat strips of iron sewn into pouches in the thick leather, and flexed my fingers vigorously to try to loosen them, I remembered the last time I had worn them, not much more than a month ago, and wished I had taken the time to dry and oil them properly before they’d been put away.

I had trotted up to the gates of my estate of Westbury in the dusk of a Sunday in mid-April, having ridden hard from Portsmouth the morning before. I was greeted at the wide-flung gates of the manor compound by Baldwin my steward and, to my delight, by Robert my son, a tall, shy, and strikingly handsome boy of eleven. I had pulled off the heavy war-gloves, tossed them to Baldwin with a warm smile as he gathered the reins of my horse, and scooped the surprised boy up in a vast bear hug.

After a long absence, I was home.

The subsequent evening had been one of merriment. Robert, once he had overcome his diffidence, had been keen to tell me everything that had happened to him since I had left for the south of France some years before and to show me his new treasures: a hunting dog called Vixen, an over-excited lurcher puppy in truth, woefully lacking in discipline; a new hunting knife that one of the few Westbury men-at-arms had made for him; a rock that glittered like gold; a phoenix’s feather, or so he claimed; and a genuine unicorn’s horn, which on closer inspection I recognised as once belonging to a mountain goat – despite Robert’s fanciful insistence that he had seen the legendary beast with his own eyes and hunted it to death with Vixen.

I partook of a delightful supper with my son and heir, served by Alice, Baldwin’s younger sister, a plain, competent unmarried woman of thirty or so years who ran the manor household with her brother with a silent competence and grace. We ate a thin venison stew and bean pottage and a sallet of wild leaves – a rather meagre feast for a returning lord, I remember thinking – and for an hour or so afterwards he and I had made not-very-tuneful but perfectly joyful music together – he on the shawm, a flute-like instrument that he had learnt to play, after a fashion, in my absence, and I on my old vielle. Then Baldwin, on the pretence of bringing me a cup of hot, spiced wine, interrupted our play and tugged me away. He insisted on speaking to me about the manor accounts. It was late for such a task and I had only been home for a few hours, so I was more than a little puzzled by his insistence. I could tell that something was amiss and so I packed Robert off to bed and he went, reluctantly, after extracting a promise from me to go riding with him in the morn.

As Baldwin and I burned a cheap tallow candle and pored over the rolls, the gauntlets lay on a window sill in the hall where my steward had left them and that, I recall clearly, was the last I saw of them before packing for the voyage across the sea.

For the news that Baldwin had for me drove everything else from my head.

I had been away from Westbury, from England, for some years, involved in that bloody carbuncle on the honour of Christendom, the hounding to death of the Cathars of Toulouse and the pillaging and destruction of their lands, but even in the far south of France I had been dimly aware of events in England during this period.

Baldwin filled in the close details: King John’s sheriffs had been rapacious in their quest for silver for their royal master, and none less so than Philip Marc, the current High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests, who had dominion over a huge swathe of central England. Marc was a mercenary, a low-born Frenchman from Touraine who had risen in King John’s service over the past ten years through his utter loyalty to the King and his savagery in dealing with the King’s enemies. And among that number were included those landowners who the King claimed owed him money. I knew Marc slightly from my days in Normandy, and liked him even less. The number of the King’s ‘enemies’ had, I gathered, risen greatly in the years I had been away. After the loss of Normandy some nine years before, John had made increasing demands on any man of even moderate wealth. Tax after tax, relief after relief, as these demands for silver were known. And these extortions – there is no better word for it – were backed up by the full force of the local officers of the law. Indeed, no fewer than six times had the King declared ‘scutage’, an arbitrary levy on men of knightly rank and above, in the time that I had been away, and not a week before my return a full conroi of the sheriff of Nottinghamshire’s mounted men had come to Westbury in mail and helm, swords drawn, and had demanded a payment of fifty marks from Baldwin.

Fifty marks! In a good year, the revenues of Westbury in total might have amounted to fifteen. Under good King Richard – and he was no sluggard at milking the country for money for his wars – I had paid two or at most three marks each year. Fifty marks was a veritable fortune.

My poor steward, with only a handful of men-at-arms to protect the manor, was outnumbered and overawed. When the knight in command, some fat-faced deputy sheriff, backed by a dark-skinned mountain of a sergeant – a demon, if Baldwin was to be believed – had threatened to burn the place to the ground if some payment in silver were not made immediately, Baldwin had believed it was his duty to protect the manor as best he could and had surrendered all the coin that Westbury possessed to the King’s enforcers: a matter of twenty-six marks, more than three hundred silver pennies, a couple of small barrels full. The sheriff’s men had taken the silver and ridden away – but they swore that they would be back for the balance in due course.

‘I am so sorry, Sir Alan,’ he said. ‘But I did not know what to do. With you away … It was not their first visit, nor yet their second or third. And each time they take something and their demands increase. I did not know what else to do, sir.’

I soothed him with the best words I could find, but my head was reeling. I had sent that silver to Westbury, as and when I could, and I had received occasional reports from the manor about Robert’s progress and a tally of the rents and so forth. But nothing for many months. I had believed that all was well, that I might return to Westbury to find the place moderately well stocked with produce and with a goodly store of cash to tide us over lean times. I’d been wrong.

Baldwin showed me on the big parchment rolls that in the past year the sheriff’s taxmen had requisitioned from me six milk cows; a dozen black pigs; a pair of oxen; two riding horses; eighteen bushels of wheat; twelve bushels of barley; three of rye; five big round yellow cheeses, and, of course, twenty-six marks of sterling silver. As the rolls proclaimed, Westbury was near destitute. Almost its entire portable wealth was now in the sheriff’s hands – and still, Baldwin told me, he was demanding more.

I had heard, even down in the war-torn County of Toulouse, that the King was squeezing the country like a ripe plum in his greedy fist, and I had even expected that, as a knight, I might have to pay a small amount to the crown for my lands. But I had not foreseen this pillaging of my goods and chattels.

Baldwin tried to give me comfort. ‘Sir, you are not alone. Most of the knights in the north – even the great barons – have suffered in the same way. I dare say all over the country there are good men doing as we are and looking with dismay at their rolls and wondering how they shall maintain their dignity over the coming year.’

It was not much comfort, to be honest. Westbury was penniless, I was near enough a beggar for all my title and lands, and the sheriff wanted more.

Baldwin looked as if he would weep at any moment, so I hid my growing anger.

‘Calm yourself, Baldwin,’ I said. ‘If the sheriff’s men return we will defy them. Tomorrow or the next day, Sir Thomas Blood will be arriving with two dozen good fighting men and the carts and baggage. Once they are installed at Westbury, we will shut the gates in their faces and dare them to attack. My men have fought halfway across Europe; they will not be cowed by a few Nottingham Castle braggarts. I’ll warrant that if needs must we can hold this place against them till Judgement Day.’

The look of relief on Baldwin’s face warmed my soul.

‘They have only preyed on us because all the fighting men were away,’ I said, slapping the old fellow on his thin shoulder. ‘They thought we were weak. Maybe we were. We are not now. I’m here to stay and I swear that they shall not have another penny, not a slice of bread from me, not a cup of stale ale. Rest easy, old friend.’

‘But in the meantime, sir, how shall we eat…’

‘Sir Thomas is bringing stores with him – rough-and-ready travelling fare, twice-baked bread, hard cheese and some wine. It will serve for now, and Thomas has silver, too. Enough to replace the farm beasts, at the very least. We shall not starve, Baldwin, never you fear. And I will ride to Kirkton tomorrow to consult with my lord of Locksley. He will know what to do.’

I rode north with young Robert the next morning. It was a fine fair spring day, sunny but brisk, with a blue sky garlanded with wisps of cloud. Robert was in a fine tearing mood, galloping ahead of me on the dry road, causing his horse to rear, then circling back to urge me to greater speed. He was proud of his riding skills, as well he might be, for they were excellent for a lad his age. But we took our time, walking the horses often to rest them and discoursing happily in the saddle about my adventures in the south and Robert’s fancies and dreams. It was approaching dusk as we rode up the steep track from the Locksley Valley to the castle of Kirkton high above.

We rode past the church of St Nicholas and I nodded courteously at the ancient priest, half-dozing on a bench in the evening sunshine on the south side of the house of God, which overlooked the valley. The old man lifted a hand in blessing but did not move, and Robert and I made our way quietly past him through to the little graveyard and up the gentle slope to the castle’s wooden walls. We were admitted without fanfare by the porters, who seemed uninterested in the two dusty arrivals. Once inside the gates, I saw that we had arrived in the middle of a celebration.

Almost the whole population of the castle, and a goodly number of the folk from the village that sprawled beneath its walls, had assembled in the courtyard – several hundred people in a rough circle around the edges with a large space in the centre. It seemed that they had been there some time, perhaps all day, for stalls had been set up offering sweetmeats, cakes and ale around the inside of the castle walls, and the crowd displayed a jolly holiday mood. On the walls of the keep, a squat tower at the rear of the courtyard, a dozen bright flags flew proudly from the battlements, and a gaggle of nobility in silks and furs stood on the parapet watching the space below.

Two men in full mail stood in the centre of that space, both armed with sword and shield. Their faces were partially obscured by their helms, which were plain steel domes, with cheek guards and nasals. One was short and stocky, the other tall and thin: by the springiness of their steps as they circled each other warily I could tell that both were young and extremely fit.

I stepped down from my horse and quickly lashed the reins to a post, and then Robert and I pushed our way to the front of the crowd to watch the bout.

The taller one attacked first, and by God he was fast. He took two steps, feinted a lunge at his opponent’s head, and whipped the sword down to strike at his foeman’s forward thigh. The stockier fellow made a slow high lateral block, to counter the feint, realised his mistake and just got his shield down in time to stop the blade cutting deep into his thigh. He was given no time to recover, for the tall fellow was already striking again, a diagonal cut at the head followed up by a thrusting pommel strike that rang off the side of the stocky man’s helmet like a church bell. It was a move I had never seen before; utterly original and devastatingly effective.

The shorter man staggered comically away from the blow, which must have partially stunned him; and the slender fellow let out a peal of boyish laughter.

It was then that I realised that the two men sparring in the courtyard were Robin’s sons: Miles and Hugh. I glanced at my own boy, standing beside me; his eyes were shining with excitement, his two fists clenched white as bone as if he too might shortly be called upon to defend himself.

The crowd were cheering, calling out advice: some of it helpful, some absurd, some of it quite obscene. Robin was standing with both hands on the parapet of the keep, flanked by two men I did not recognise, and looking down impassively as his two boys battered away at each other. Hugh had recovered himself by then, which was just as well, for young Miles was subjecting him to a blizzard of strikes, each as fast as a darting kingfisher, a dazzling display of his sword-skill. Metal flashed in the spring sunlight, white chips of wood flew from Hugh’s shield, and the sword clanged once more against his brother’s helmet as it skimmed its pointed dome. But Hugh did not go down. He hunched himself under the onslaught, and his blocks and parries were exactly precise, a classic defence – standard, tried-and-tested moves and would have filled any master-at-arms’s heart with joy. Miles struck fast and hard, often in the most unexpected combinations, but Hugh’s bulwark was solid; every time Miles’s sword licked out, there was Hugh’s battered shield ready to take the blow, or his blade to make the block.

And I could see that Miles was tiring.

For any man, no matter how strong and fit, tires after only a short while in the fury of combat. No one can fight at full pitch for long; and wiser, older warriors know that if they can survive the initial onslaught, their enemy will be weakened, and they will surely have their chance. Hugh was no grey-beard, he was in his twenty-fifth year, but he had the patience and wisdom of a man twice his age.

Miles’s sword strikes were still coming fast as a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...