- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

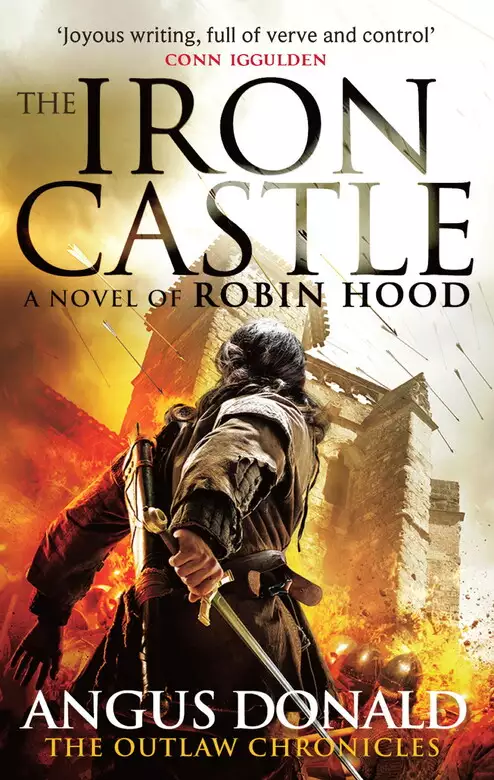

AD 1203: ROBIN HOOD MUST TURN THE TIDE OF WAR

Normandy Ablaze

AD 1203: England and France are locked in a brutal struggle for power. The fate of the embattled duchy of Normandy is in the hands of the weak and untrustworthy King John. Facing disaster, he calls for help from a former outlaw - Robin Hood.

The Earl of Locksley

As King Philip II's army rips through the Norman defences, Robin - the Earl of Locksley - leads a savage mercenary force into battle under the English banner, supported by his loyal lieutenant Sir Alan Dale. But defeat is only one castle away.

The Iron Castle

The most powerful fortress in Christendom, only Château Gaillard can resist the French advance. Robin and Alan must defend this last bastion against overwhelming force - for if the Iron Castle falls, Normandy will fall with it.

Release date: July 3, 2014

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Iron Castle

Angus Donald

My own time in this world is, I fear, drawing to a close. I have lived nearly three score years and ten – far longer than most men – and I have seen much of battle and hard living, both of which exact a heavy tax from a man’s soul. My whole body hurts in these end days of my life: my legs swell red and ache, my fingers tremble and throb, old bones broken years ago complain when I try to sleep, in whatever position; my back twinges when I move swiftly and when I do not move for long stretches of time, my breath is short and foul, and my kidneys give sharp expressions of protest every day just before dawn, even though I piss five times or more during the night. I am old, that is all, and nothing can be done for it – my physician seems to have no inkling of what exactly ails me and mumbles about my humours being out of balance and the unfortunate alignment of the stars, the damned ignorant quacksalver, before taking a pint of blood from me, and a purse of silver, too, for his trouble.

I am hampered in my efforts to set down this tale, not only by my failing health, but by the presence of my grandson and namesake, Alan, here at the manor of Westbury, in the fair county of Nottinghamshire. The lad is now eighteen years of age – a fully grown man and a trained knight, skilful with sword and lance. But he has lost his place with the Earl of Locksley at Kirkton Castle. He trained there as a squire for five years or more and last year the Earl did him the honour of knighting my grandson himself – he did this, I believe, not for any prowess that young Alan showed at arms, but as a mark of respect for the long friendship I had with his father, Robert Odo, who was my lord before him and who is now, sadly, in his grave. The young Earl has a great respect for tradition, and as I loyally served his father, it seemed he wished for my grandson to serve him as a knight. But something has happened, I know not what, and young Alan has returned to Westbury in disgrace. He refuses to tell me what is amiss and I must summon up the vigour in these old bones to ride up to Kirkton, in south Yorkshire, and find out for myself what has caused this grave rift between our two families.

Meanwhile, young Alan has decided to fill his life with noise and merriment. He has invited a pack of young, well-born louts to stay at Westbury – he calls them his comrades-in-arms, though neither he nor they have ever fought in real battle – and they spend their time hunting deer, hares, wild boar (anything that moves swiftly), all over my lands, and then returning to Westbury, filthy with mud, their horses blown, and with a thirst that would rival a Saracen’s camel train. Since they arrived, a week hence, they have been working hard to drink my wine cellars dry night after night. I have already had to place a fresh order for another two dozen barrels with my Bordeaux merchants, the second one this year, and it is not yet October. I will need to order again before Christmas, I make no doubt.

Their wild antics, their drunken bellowing, their endless inane laughter keep me awake at night, even though their revels take place in the guest hall fifty yards from my quarters; and, poorly rested when I rise at dawn, my irritation grows with each passing day and my rising bile prevents me from concentrating satisfactorily on my labours on this parchment with quill and ink. I should admonish him, I know, but I love him – he is my only living issue, his father, my only son Robert having died of a bloody flux more than ten years ago – and I too was young once and enjoyed a cup of wine or two with friends, and a little mirth. So I believe I can endure a measure of youthful rowdiness for a little while longer.

And for now, at this hour, Westbury is mercifully quiet, praise God. It is not long after dawn, a pleasingly chilly, misty morning, and young Alan and his friends are sleeping off their surfeit of wine. I must seize this opportunity and begin to scratch out my tale, the tale of the great battle, perhaps the greatest battle of them all, a long and truly terrible siege, that I took part in forty-odd years ago in Normandy; and the part played by my lord, my friend, the former outlaw, the thief, the liar, the ruthless mercenary, Robert Odo, the man the people knew as Robin Hood.

The great hall of Nottingham Castle was warm and dry and, for once, adequately illuminated against the shadows of the raw spring evening. A large rectangular building in the centre of the middle bailey of the most powerful castle in central England, the hall had been the scene of many uneasy moments for me over the years. I had been insulted, mocked and humiliated here as a youngster; I had fought for my life several times in its shadow. This beating heart of the castle had once been a place that I feared and avoided. But on this day, on the ides of March, in the year of Our Lord twelve hundred and one, I was a privileged guest within its embrace. It was bright as noon within, with the cheerful yellow light of scores of fat beeswax candles held fast on spikes in a dozen iron ‘trees’ – six along each long wall – and a leaping blaze of applewood logs in the centre of the open space. Had it not been for the presence of fifty English and Norman knights standing awkwardly in murmuring clumps and dressed in all the finery they could muster, it might have been a cosy, domestic scene.

Clearly the newly appointed Sheriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests, Sir Hugh Bardolf, the constable of the castle, wished his most honoured guest to be at ease, and wisely so: for this guest was none other than the King himself – John, only living son of old King Henry, and lord of England, Ireland, Normandy, Maine, Anjou, Poitou and Aquitaine.

I must admit I despised the fellow, King or no. To my mind, John was a cowardly, cruel, duplicitous fool. He had tried to destroy me on several occasions and I had survived only by the grace of God Almighty and the help of my friends. I had no doubt that if he ever brought himself to recall some of our past encounters, and he thought there would be no repercussions, he would seek to have me dispatched forthwith. I felt the same about him. Indeed, I would have happily danced barefoot all night on his freshly filled grave. But I continued my existence on this earth, as a minor knight of the shires with only one small manor to his name, because I was just too insignificant for the King to notice. I was, indeed, beneath his royal contempt. I also had a powerful protector in the form of my lord, Robert Odo, erstwhile Earl of Locksley, a man who, at this very moment, was kneeling humbly before the seated King, his arms outstretched, palms pressed flat together as if in prayer. My lord, I knew for certain, hated King John quite as much as I did. And yet here he was on his knees in humble submission before him.

Robin was bareheaded and unarmed, as is the custom for these ceremonies, dressed only in a simple grass-green, ankle-length woollen robe. His light-brown hair was washed and neatly cut and combed, his face freshly shaven. He looked solemn, meek and pious, almost holy – if I had not known him so well, I’m not sure I’d have believed that this clean and spruce and humble fellow was once the famous thief and murderer Robin Hood. I was still having difficulty encompassing in my mind what I knew was about to happen. My lord, once good King Richard’s most trusted vassal, and more recently the scourge of wealthy travellers in Sherwood, was about to swear homage to the Lionheart’s cowardly younger brother. Incredibly, before my eyes, Robin was about to make a solemn vow that he would always be King John’s man.

I was shaken to my boot soles when Robin told me, a month earlier, of his decision to give up his outlaw life in Sherwood and make his peace with the King.

‘I’m tired of all this, Alan,’ Robin said, over a cup of wine in the hall of my own small manor of Westbury, half a day’s ride north of Nottingham. His clothes were little better than greasy rags. His hair was shaggy, hanging past his shoulders and I could see burrs, twigs and clots of dirt in it. A fuzz of brown beard hid the lower part of his lean, handsome face – but his eyes blazed silver in their intensity as he told me his plans.

‘It was wonderful when I was a youngster,’ he said. ‘I was truly happy – living free of all constraints, doing whatever I wished, whenever I wished to do it. The danger was a tonic to my soul. I danced each day on the edge of a sword blade – and adored every moment. But, now … now, I miss my wife and my children. I think about Marie-Anne and Hugh and Miles far away in France. I want to see their faces and hold them. I want to watch Hugh and Miles grow tall. I want to live at Kirkton – all of us together. I want the quiet life, Alan, the dull life of the good man; I want to husband the Locksley lands, see the sheep sheared in spring and the crops brought in in summer; I want to bring justice and peace to the people who live there, and sleep safe in a warm bed at night. I don’t want to be constantly in fear that I will wake looking up at the killing end of a spear-shaft, surrounded by the Sheriff’s men. I don’t want to end my days on a gibbet, rough hemp around my neck, slowly choking out my last breaths in front of a jeering crowd. I want…’ He huffed out a breath, lifted his chin and straightened his shoulders. ‘I want, I want, I want – by God, I sound like a whining brat. My apologies, Alan. I must be getting old.’

That was exactly my interpretation, too. Robin, by my calculation, had now seen thirty-six summers – a goodly age, and one at which a man has one eye fondly on his wild, adventurous youth and the other on the loom of his dotage. I understood my lord’s impulse. I was ten years younger than Robin, but I too felt the lure of domesticity and secretly hoped that my years of battle, bloodshed, constant fear and mortal danger were behind me.

‘William is going to fix it,’ Robin said. ‘My brother is well with King John, it appears. He has spoken to Bardolf, who seems a decent man – for a damned sheriff – and although I must pay an enormous bribe and bring myself to kneel and do homage to King John, I will eventually be allowed to take up my lands and titles again in Yorkshire, and Marie-Anne and the boys can finally come home.’

‘Eventually?’

‘Yes, eventually. John, for all his many faults, is not a total imbecile. He wants me to serve him faithfully in France for three years – he has even drawn up a charter to this effect – and then I will be allowed to retire to the Locksley lands. He’s also giving me the lands in Normandy that Richard promised – do you remember? – as a sweetener. It’s a good arrangement for both of us. Three more years of fighting, then home with Marie-Anne and the boys. Don’t look at me like that, Alan; while John might not be, let us say, the most palatable fellow, he is still our rightful King.’

I breathed in a mouthful of wine, coughed, spluttered and mopped my brick-red face with a linen napkin.

‘Not the most palatable fellow? Our rightful King? Are you quite well?’

Robin looked annoyed. ‘Don’t climb up on your high horse, Alan. What am I supposed to do? Spend the rest of my days living alone like a hunted beast in the wild? Staying outside the law because John behaves like a petty tyrant from time to time? He’s the anointed King of England, sovereign over us all, he’s entitled to be a little high-handed. And I can change him. I can. If I’m at his side, I can curb his excesses, guide him, help him be a better man, a better King…’

I said exactly nothing. I cautiously took another sip of my wine.

Robin frowned. ‘Damn you, Alan, I am doing this whether you approve of my actions or not. The King wants me to raise a mercenary force in Normandy, nothing too unwieldy, two hundred men-at-arms or so, some archers and cavalry, too. The money is very good, and…’ Robin cleared his throat and smiled slyly. ‘Well, I wondered whether you would care to climb down from that lofty horse and agree to serve for pay on a hired mount on the continent. Good wages for a knight: John is paying six shillings a day; there would be the usual spoils, too. It might be fun…’

This was a most generous offer from Robin. I held the manor of Westbury from him, as the Earl of Locksley, and I was, in truth, obliged by custom to serve him as a knight for forty days a year, if he called upon me to do so. But Robin had never asked me to fulfil this obligation and, although I had served him in many a campaign and fought many a bloody battle under his banner, it was always out of love and loyalty rather than duty.

‘By your leave, sir, I will remain here at Westbury,’ I said formally. ‘The manor is in poor condition and urgently needs my attention, as does baby Robert. But, more than that, I believe my fighting days are behind me at last. I’ve had enough of pain and bloodshed, enough of foul food and festering wounds, of good men dying for bad reasons. I would be a lord of the land from now on.’

‘As you wish, my friend,’ said Robin. ‘I will not force you. If you change your mind, there will always be a place for you in any force that I command. Just don’t go around speaking ill of our noble king. Apart from being most offensive to those of us who would be his loyal vassals, it’s treasonous. John is very alive to threats of treason. Royalty should be shown the proper respect.’ Robin grinned at me to show he was jesting, and I could do nothing but smile back.

I tried my hardest to show the proper respect to royalty, and to Robin, to the extent of donning my best clothes and attending this royal ceremony of homage at the great hall in Nottingham Castle that cold March evening. Yet in the peacock swirl of the nobility of all England, I felt very much like a drab nobody. I was not nobly born myself and had very little wealth in either lands or silver – my father Henry Dale had been a monk, then a musician, then a peasant farmer before his early death – and I earned my knighthood on the battlefield with King Richard. On that day in the great hall, I was conscious of the fact that my only good cloak had recently been torn on a nail, then mended by one of my elderly female servants. The stitches were crude and lumpy; they showed up like a stain, proclaiming: look, this gutter-born oaf cannot afford a new garment even for a royal occasion.

The mending of my cloak made me long once again for my sweet wife Goody, who had been killed in a terrible accident the year before. My lovely girl would have repaired it, quietly, efficiently and no one would have been the wiser. But it was not only for her needlework that I missed her. I had known her since we were both children; we had, in a way, grown up together, and I had loved her with all my heart – her loss was sometimes overwhelming. I still wept from time to time, alone in bed, when I suffered the lash of her memory.

‘I never thought I’d see the day Robert of Locksley would bend the knee to King John,’ said a deep voice at my shoulder, shaking me from my sad reverie. I turned to see a tall, gaunt form, with grizzled grey-white hair, muscular shoulders and big scarred hands. He was dressed richly, in silk and satin and velvet, as befitted one of England’s richest men, and yet on William the Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, the outfit looked absurd, like a broad-shouldered, hairy soldier got up in a woman’s dress for a fair-day lark. I felt that he’d have been much more comfortable in well-worn iron mail from top knot to toe, a garb I had seen him don on countless occasions on campaign.

‘Why is he doing it, d’ye know, Sir Alan? You know him best of all. What’s cunning old Robin Locksley up to this time, eh?’

‘He says he’s tired of sleeping in the woods. He’s getting old, he says. He wants to retire to his lands in Yorkshire and live in peace.’

‘Hmmf,’ said the Marshal. ‘He’s barely a stripling. He’s not even forty. I hope he hasn’t gone soft. We need him; we’ll need all our good men in Normandy before long, you mark my words, Alan.’

Just then we were joined by two men. One was a neighbour of Robin’s, a stiff-necked baron called Roger de Lacy, who held Pontefract Castle for the King, and of whom I had always been slightly in awe. He was short, square, with fierce dark eyes, and his manner was habitually brusque, bordering on rude. De Lacy had a reputation as a fearsome fighter, a man with contempt for any weakness in others and himself, but he was said to be as true as Damascus steel once he had given his oath.

‘Pembroke,’ he said, with a curt nod at the Marshal. Then: ‘Dale – didn’t bother to dress up for the occasion, I see.’

I wrenched up a smile but made no reply.

The other man was a tall, smiling, open-faced stranger, clearly a knight by his garb and manner, but with a gentleness and humour shining from his eyes that seemed oddly unwarlike. He was accompanied by a girl. Not just a girl, in fact, but a vision of such beauty that I had difficulty paying full attention to the stranger’s name and rank, when the Marshal introduced him.

‘I beg your pardon,’ I stammered. ‘What name did you say?’

She was about eighteen or nineteen, I judged, with skin so pure and white it seemed like the palest duck-egg blue, glossy sable hair under a snow-white headdress, a heart-shaped face, wide mouth, small nose and happy blue-grey eyes.

‘Are you deaf, Alan – what ails you?’ said the Marshal. ‘Here is Sir Joscelyn Giffard, lord of Avranches in Normandy, and his daughter the lady Matilda.’

‘Everyone calls me Tilda,’ said the girl, in a low, smoky voice, and when she smiled I felt a delicious rush of blood through my veins. She reminded me of Goody – her colouring was entirely different, Goody had been peach-pink and golden whereas this lady was swan white and midnight dark, but there was a calm joy in her perfect face that put me in mind of my beloved. I tore my gaze from her and, my head reeling like a drunkard’s, I bowed to Sir Joscelyn and bid him a stammering welcome to Nottinghamshire.

A blast of trumpet saved me from having to make conversation with these men. A young and spritely bishop entered the hall bearing a tiny golden casket on a plump purple cushion. Many of the more pious assembled knights fell to their knees as the bishop and his burden passed – for that bright little box housed a sacred relic, a toe-bone from the body of the blessed forerunner of Our Lord Jesus Christ, John the Baptist himself – but I remained standing when the holy man went by, as did William the Marshal. I had had some experience of so-called relics in recent years and, as a consequence, I was no longer so swift to afford them all deep reverence.

The bishop stopped beside the kneeling form of Robin and the seated form of the King and stood between them. There was a second trumpet blast – ordering silence in the hall – and John spoke, his voice rusty, harsh, almost a frog’s croak.

‘Good. Right. Everybody quiet. Let’s begin.’ The King glanced down at his right hand where I could see he held a scrap of parchment. He cleared his throat.

‘Are you willing, Robert Odo, son of William, Lord of Edwinstowe, to become my man?’ The King squinted down at his hand. ‘Do you choose to do so with a pure heart in the sight of God and in the absence of all deceit, falsehood and malice?’

‘I am willing,’ said Robin clearly.

King John tucked the parchment under his thigh and placed his two hands over my lord’s, and holding Robin almost captive for a moment, he looked at him and said, ‘Then from this moment forth you are my sworn man.’

And he released his grip.

The bishop spoke then: ‘This homage that has been made in the sight of God and Man, and in the presence of this holy relic, can never be unmade. Thanks be to God.’ Then he said, ‘Are you now willing to swear fealty to your sovereign lord for the lands and titles of the Earl of Locksley?’

‘I am willing,’ said Robin, and he placed his right hand softly on the little golden box on its rich, velvet cushion. ‘I swear, by my faith in Our Lord Jesus Christ, that I will from this moment forward be faithful to my lord and sovereign King John and that I will never cause him harm and will observe my homage to him against all enemies of my lord in good faith and without deceit.’

Robin lifted his hand and, knowing what I did about my lord’s larcenous nature, I half-expected the little golden box to have disappeared into his palm, but it was still there, gleaming on that purple cushion.

To his credit, John also seemed to play his part in a true and honest manner. He raised Robin to his feet and they exchanged the ritual kiss of peace. The trumpets flared again. John said loudly, ‘Fare you well, my true and trusty Earl of Locksley!’ Then he handed Robin a roll of thick parchment, very softly patted him on the cheek and whispered something into my lord’s ear. Robin bowed low in one graceful, fluid movement and backed away from his new master.

Amid much slapping of his back and many a shouted word of encouragement, Robin made his way through the crowds of knights and nobles and, still clutching the roll of parchment, he came over to our group, to Sir Joscelyn, his daughter Matilda, Roger de Lacy, William the Marshal and myself.

I congratulated my friend, as did the Marshal, and Robin smiled ruefully, humbly and said little. De Lacy said, ‘That’s an end to all your damned Sherwood nonsense, Locksley. You are the King’s man now and you’d best not forget it.’ Robin smiled and inclined his head in agreement. Then Sir Joscelyn gripped him by the right hand and pumped it firmly.

‘The King is fortunate indeed to have a good man such as you as his vassal,’ he said, beaming at Robin. Tilda, I noticed, kissed my lord softly on his cheek and asked after Marie-Anne and his children. Robin answered her briefly but with great kindness and courtesy. I asked Tilda if she knew Marie-Anne well – a silly question, given that she had just asked after her health, but for some reason I wanted her to give me her attention. She said that she did and that they had been together in Queen Eleanor’s court in Poitiers for some time the year before. I asked a few questions about the court, again just for the pleasure of hearing her speak and having her lovely eyes fixed on mine, and then she surprised me.

‘Your name is well spoken of there, Sir Alan,’ she said. ‘Some of the Queen’s ladies are avid for music and your name has been mentioned as one of our finest trouvères – perhaps you will play something for me one day. Or better yet, perhaps you will even write one of your famous cansos about me! Something terribly scandalous – I hope.’ She poked the tip of her pink tongue out of the corner of her mouth an instant after she said this, to show that she was not completely in earnest. It was the most enchanting thing I’d seen for an age. And I found myself shocked and aroused at the same time. A canso was a song, usually about love, about adulterous love, between a knight and a lady. By God, by all the saints, the minx was actually flirting with me – and Goody not yet a full year in her grave.

I blushed beetroot red and mumbled something about being delighted, if time and my duties permitted, then I turned to William the Marshal and asked him in a gruff voice for news of the war on the continent. With one part of my mind, I wondered what it would be like to touch Tilda’s pitch-black hair, to run my fingers through it. Would it be coarse? What would it smell like? I had to wrench my mind back to what the Marshal was saying.

The Lusignans were stirring up rebellion in Poitou and Aquitaine, the Marshal said – and the other men huddled in to listen, too – but it was nothing serious, a little looting and livestock theft, no more; and King Philip had his envious eyes on Normandy, as usual, although in this seasoned warrior’s opinion the treaty signed recently at Le Goulet, a solemn compact between the kings of England and France, ought to restrain him for some months to come.

‘There is not all that much going on just at the moment,’ sighed the Marshal. ‘Even Duke Arthur of Brittany has dropped his claim to the Angevin lands. Philip made him do so – in the name of peace between England and France.’

‘There seems to be a terrible danger of a long-lasting peace breaking out,’ said Robin, to much knightly guffawing. I stole a glance at Tilda, and from under her long dark lashes she caught my eye and smiled shyly. I blushed again, looked away, and resolved to restrict my thoughts to proper masculine affairs.

‘There can be no real peace until Philip is defeated,’ said de Lacy, thrusting out his chin. ‘While he can still field a force of two thousand knights, and twice as many men-at-arms, Normandy will not be safe. And God help the man who doesn’t understand that. Philip must be crushed. Utterly destroyed.’

Sir Joscelyn coughed. ‘It might well be possible to have peace, if the King were to agree to hand over a small part of Normandy to the French. The Vexin, perhaps, some of the eastern castles…’

‘Nonsense!’ De Lacy’s interruption was an axe blade cutting through Giffard’s words. ‘The King must hold his patrimony, every part of it. It was given to him by God, and it is his sacred duty to guard it for his heirs and successors. Every castle, every town, every yard of land. If he shows the slightest weakness, he will lose the whole damn lot in double quick time.’

I kept my eyes on Robin’s face as the talk of war and peace, of alliances and shifting loyalties rolled over me. There was something a little strange about my lord’s demeanour this evening. On the surface he seemed perfectly happy, now reconciled with his King, no longer an outlaw, and once again restored to the title of Earl of Locksley – even if he had three years of service yet before he could fully come into his lands. He should have been contented, joyous even; this was his day and, indeed, he appeared happy. He was witty, irreverent; he seemed serenely in command of his life. Yet I knew in my heart he was furious. I had known him half my lifetime then, and I could tell, if nobody else in that bellowing throng could, that he was boiling with a suppressed and very violent rage.

After perhaps an hour, Robin took me by the elbow. ‘Let us take some air,’ he said. We disengaged ourselves from the gathering and walked out of the hall into the middle bailey. Robin looked up at the night sky, scattered with uncaring stars and lit by a low silver moon.

I waited in silence for him to speak.

‘He did not set his seal on this,’ said Robin finally, lifting the rolled parchment that he was holding. ‘My rights, my obligations, the extent of my lands – it’s all here in an elegant clerkly hand in beautiful Latin. But it means nothing without his seal. It’s just a scrap of animal skin with no force in law.’

‘I’m sure he’ll set his seal on it when your three years are up,’ I said.

‘Are you? I wish I were.’

I said nothing.

‘I do not see what else I could have done,’ Robin said. There was an oddly plaintive tone to his voice that I did not much like. ‘Surely Marie-Anne and the boys must have a home?’

There was no ready answer to this, so I remained mute.

‘Are you sure you will not come with me to Normandy?’ he said after some little time had passed.

‘I cannot,’ I said. ‘Truly, I cannot. Westbury is greatly impoverished; I have sorely neglected it of late. And little Robert has been motherless since Goody died. I must raise him and the fortunes of Westbury together. I am sorry, my lord.’

‘A shame. I could have done with a good man at my side, one of my own people,’ said Robin. ‘Someone I can actually trust,’ he added with a sideways smile.

‘What did the King whisper after you had made the oath?’ I asked, not expecting that he would tell me.

He didn’t, for a long time.

‘It was nothing,’ he said, finally. ‘Nothing at all important.’

‘What did he say?’

Robin looked at me, and I could see the silver sheen of his strange grey eyes in the darkness: ‘He said four words, Alan. Only four – but I think I will be hearing them in my head for the rest of my life.’

‘What did he say?’

‘He said, “There’s a good boy.”’

The harvest was bad that summer in Nottinghamshire. Towards the end of August, when the wheat was just beginning to turn gold in the fields, angry violet clouds massed like demon armies, came charging forward and dumped an ocean over Westbury. The harvest died in the fields, trampled flat by a deluge that would have sunk the Ark. For two solid weeks the pouring Heavens battered the standing corn. I

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...