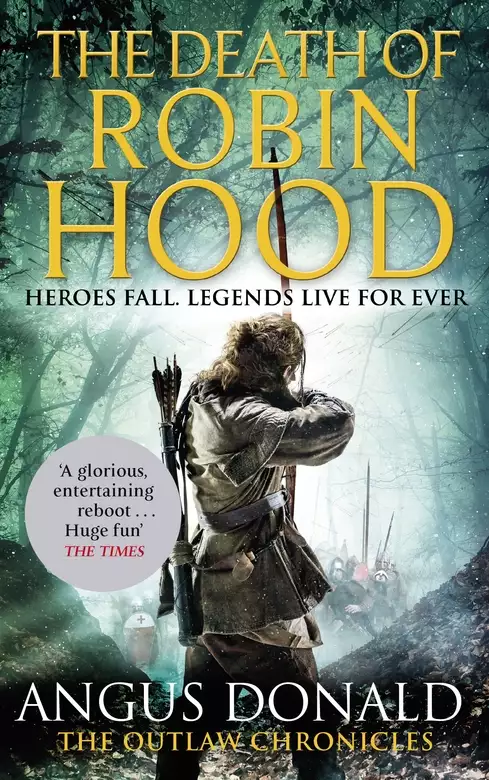

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

"I charge you, Sir Alan Dale, with administering my death. At the end of the game, I would rather die by your hand than any other."

England rebels

War rages across the land. In the wake of Magna Carta, King John's treachery is revealed and the barons rise against him once more. Fighting with them is the Earl of Locksley - the former outlaw Robin Hood - and his right-hand man Sir Alan Dale.

France invades

When the French enter the fray, with the cruel White Count leading the charge, Robin and Alan must decide where their loyalties lie: with those who would destroy the king and seize his realm or with the beloved land of their birth.

A hero lives for ever

Fate is inexorable and Death waits for us all. Or does it? Can Robin Hood pull off his greatest ever trick and cheat the Grim Reaper one last time just as England needs him most?

The climactic episode of The Outlaw Chronicles is the most explosive yet - but who will survive and who will fall when the final reckoning comes?

Release date: August 4, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Death of Robin Hood

Angus Donald

It was a forbidding fortress, one of the mightiest in England, built to guard this crossing of the river on the road from Dover to London, the most direct route an invading enemy would take to attack the largest and richest city in England. Yet the castle’s dominating stone, its implacable solidity, was of great comfort to me. Battle was surely coming – a day or two, a week at most, and it would be upon us in all its blood and agony and fury, and then, when the arrows began to soar, the steel to scrape and men to scream in pain, I knew I would be more than grateful for the castle’s twelve-foot-thick walls that climbed a hundred feet into the air.

The east wind was freshening, wafting a light mizzle from the cold waters of the estuary a couple of miles behind my back, and I pulled the damp green cloak tighter around my shoulders. My stomach gurgled unhappily – it must surely be almost time for supper and my relief – and I rubbed my reddened hands together and stamped my numb feet. By night’s fall I should be snug in the guardhouse on the southern side of the bridge – there would be hot mutton broth and fresh bread and butter, a cup of warm spiced wine and the company of old friends. But where the hell was Sir Thomas Blood? The sun was already squatting on the western horizon.

I looked hopefully to my left towards the stout two-storey wooden box arching over the planks of the bridge on the southern bank. Was I imagining it or could I already smell the broth? A pair of thick-set men in green cloaks, long yew bows in their hands, were propped against the rail staring silently over the water, vacant as cows at a gate. I looked right, past the piles of boulders, each roughly the size of a human head, collected below the rail in little cairns of three or four rocks every ten feet, and saw a young, slim, fair-haired swordsman, similarly green-cloaked, fifty paces away at the northern end of the bridge. He leaned over the rail and lowered his head, and I saw a gobbet of spittle shoot from his mouth and disappear below. Perhaps inevitably, echoing up from underneath, came the faint roar of a complaint, its maker at first unseen from my vantage point. A slim rowing boat emerged, heading upstream, with a red-faced bald fellow mopping his pate and shaking his fist at the handsome young devil laughing above him.

‘Don’t do that, Miles,’ I bellowed. ‘It’s churlish, it’s unseemly … it’s plain disgusting, for God’s sake.’

The young man turned to look at me. His long, lean face seemed lit from within, like the All Souls’ candle inside a hollowed-out turnip, illuminated by a mischievous almost child-like delight.

‘I’m bored half to death, old man,’ he shouted back. ‘Bored as a boy-loving eunuch in an all-girl brothel. Surely our watch must be over by now. Besides, that baldy fellow sells bad fish. He’s a cheat. Father says so. That basket of carp he sold us yesterday was mostly mud, skin and bones.’

His father, of course, was my lord, the Earl of Locksley, my old friend Robin, who on this chill October day was, no doubt, sitting in the warmth of the guardhouse toasting his boots by a brazier. But, even if Miles’s father had not been my lord, I would have been loath to scold the youngster – despite him daring to call me an old man. Not only because I liked his irreverent high spirits, which cheered the hearts of our whole company, but also because he was a fine fighting man in his own right, a quicksilver fiend with a blade and utterly fearless in the storm of battle.

Apart from the angry fisherman, now pulling away at a pace, leaving a string of ripe insults in his wake, the river upstream was as placid as a pond. A few ancient craft lay hauled up on the slick banks and two old salts sat on boxes, their heads bent together, knitting their nets slowly, rhythmically, from time to time pausing to pass a leather bottle between them. I turned around, full into the cold breeze, the drizzle spitting directly in my face, and looked towards the curve of the river where it disappeared into the low pasturelands. Nothing but slow brown water and low grey fields, and a few scattered sheep casting monstrous shadows, as the sun nestled down behind me. Not an enemy in sight. Not a sniff of danger either. I could have been safe and snug at home in my manor of Westbury in Nottinghamshire rather than doing sentry duty on a mist-sprayed bridge in the flatlands of east Kent.

I heard a discreet cough. ‘Sir Alan,’ said a deep voice behind me and I turned to behold a short, powerfully built, dark-haired knight in full mail, helmet under one arm, smiling up at me.

‘About time, Thomas,’ I said. ‘About bloody time. All quiet. Nothing to report. This godforsaken bridge is all yours.’

As I stepped into the guardhouse, I saw my lord seated at the long table in the centre of the room, spooning the last drops from an earthenware bowl. A battered, soot-blackened steaming cauldron had been placed in the middle of the board, next to a basket of bread, a jug of wine and a stack of crockery.

‘Report?’ said Robin.

‘There is nobody out there,’ I replied, reaching for a bowl. ‘If John really is coming here, he is taking his own sweet time about it.’

‘Oh, the King is coming all right,’ said Robin cheerfully. ‘He has to. His new men, his Flemings, will surely cross the Channel and land at Dover, and we bar the route to London. He must take Rochester, if he wishes to take London from the Army of God. And he must take London if he wishes to win this war.’

The so-called Army of God, under the command of the less-than-saintly Robert, Lord Fitzwalter, did indeed hold London. Robin and I had stormed the walls for him just over three months ago and as a result we had captured the capital and been able to force the King to set his seal on a great charter at Runnymede, a document that was supposed to guarantee the rights of free Englishmen for ever. But, despite solemnly swearing to abide by the charter, calling for peace in the land and renewing the oaths of loyalty with his barons, the King had renounced the agreement a mere handful of weeks afterwards. The Pope in Rome, at the King’s behest, had damned the charter, too, as shameful and illegal and had excommunicated all the rebel barons.

We had struggled and suffered and bled for that square piece of smoothed calf skin, and wrangled day and night over the terse Latin words it contained. Yet despite Robin’s insistence that by forcing the King’s hand we had struck a blow for liberty that would be remembered for generations to come, I sometimes wondered what all the strife and bloodshed had achieved. If it had, in fact, achieved anything at all. King John, that cowardly, murderous snake, had simply ignored the great charter and spent thousands of pounds in tax silver recruiting fresh mercenary troops from Flanders and northern France. War had broken out again almost immediately between the rebel barons and the King’s new continental hirelings.

Nevertheless, our position was not hopeless. Since the sealing of the charter, many English barons who had previously been fearful of resisting the King had rallied to our cause – the Pope’s mass excommunications notwithstanding. Indeed, the constable of this very castle, Reginald de Cornhill, once a staunch King’s man, had opened its gates to Lord Fitzwalter and his men not two days before and declared himself a lover of liberty, before departing with unashamed haste and all his men for his lands in Surrey.

Yet we rebels held London, and Exeter in the south-west, and a scatter of small castles in the north – and now we held Rochester too. And, while Fitzwalter prepared the defences of this mighty fortress with his grizzled captain William d’Aubigny, Robin’s detachment of twenty archers and a dozen men-at-arms had been given the task of holding the bridge. For the King was surely coming up from Dover. And I knew it just as well as Robin.

The door of the guardhouse crashed open, impelled by an impetuous boot. ‘Do I smell yesterday’s mutton broth?’ said Miles, striding inside and unfastening the golden clasp to drop his wet green cloak on the dirty rushes of the floor. ‘Isn’t there anything a bit more substantial to eat? I could make short work of a bloody beefsteak or a dripping roast chicken – God’s bones, that would suit.’

‘It’s broth or nothing,’ said his father, with an edge in his voice. ‘You know as well as I that we are on short commons, all of us, till the supply train comes through from London. We must tighten our belts till then. And do try not to whine quite so much, son.’

‘Not whining. Just making polite dinner conversation.’ Miles plonked himself down on the bench next to me, helped himself to a clay bowl and filled it to the brim. ‘Mmmm. Mutton broth. Nice and watery. And plenty of gristle, too, I see.’

I could actually hear Robin grinding teeth. But my lord held his peace.

‘What news from the castle?’ I said, after a long uncomfortable pause.

‘D’Aubigny has it nicely in hand, I believe,’ said my lord. ‘He says the fortifications are sound, the walls in good repair throughout, and he has enough men and arms to hold it for months against a determined assault – providing of course that sufficient food stores can be brought in.’

William d’Aubigny was a bear of a man, immensely strong and quick, and with a reputation for ferocity in battle. He was lord of Belvoir Castle, a fortress in Leicestershire about fifteen miles east of Nottingham. As a not-too-distant neighbour of ours, he was well known to Robin and to me.

‘Fitzwalter is planning to leave us, though,’ Robin said.

‘What?’ I said, swallowing a mouthful of hot soup too quickly. ‘Why?’

‘He says he’s needed in London. A grand council of the barons has been called. They’re to discuss recruiting aid from overseas and Fitzwalter says he must attend or who knows what foolishness will occur.’

‘So our gallant commander is deserting us on the eve of battle?’ said Miles. ‘Scuttling back to London. Hardly inspiring behaviour in a leader.’

Robin ignored his son and concentrated on wiping clean his bowl with a crust but I felt called on to defend Lord Fitzwalter’s honour. My relationship with the captain-general of the Army of God had not always been cordial but since the war began I had grown to like the man.

‘He is our leader and it makes sense that he should attend this important council with all the other senior barons,’ I said.

‘Were you not invited to attend this vaunted gathering then, Father?’ said Miles. ‘How strange! Perhaps they feel that playing watchman on this ancient bridge is more your mark.’

I could have punched the lad off the bench for that insult. Indeed, I felt my right fist clench and rise from the board. But Robin beat me to it.

‘The sentry on the roof has been complaining of the cold this past hour,’ said Robin serenely. ‘When you have finished that nourishing bowl of broth, Miles, get yourself up there and take his place. I’ll be sure to send someone up to relieve you at midnight’ – Robin pretended to think – ‘or perhaps at dawn. We’ll have to see. I’d like all the serious fighting men to get a good night’s rest.’

‘But, Father, I had plans to visit the town tonight. There is this girl I want to see and as I’m not on duty—’

‘Well, you are on duty now,’ said Robin. ‘Off you go.’

‘But it’s not fair …’

‘Don’t whine, lad,’ I said, perhaps a touch smugly. ‘Obey your lord’s command.’

Miles opened his mouth to argue but before he could speak the door swung towards us and we all three looked up in surprise at the dark entrance, now wholly filled by Sir Thomas Blood’s short form, broad shoulders and steel-helmeted head.

‘Boats, my lord,’ said Sir Thomas. ‘Boats on the river. Scores of them.’

From the roof of the guardhouse, we had our first glimpse of the enemy, of the feared Flemish legions of King John. At least fifty rowing boats, downstream, three hundred yards away. Each boat was showing a single pinprick of yellow light, a lantern or open fire-pot, enabling us to see them against the blackness of the water in the failing light, and every vessel was pulling hard for the centre of the bridge.

‘Miles, get back to the castle now. Alert Lord Fitzwalter – tell him … tell him that the bridge is under attack by several hundred of the King’s men and that we will hold as long as we can. But it cannot be for long. Tell him to come with all speed.’

‘But I want to fight. If you send me away, I’ll miss everything—’

‘For once, Miles, just do as you are bloody well told!’ My lord did not raise his voice above a murmur but there was a whip-crack in his tone that sent his younger son scurrying for the wooden stair.

‘Now, Alan, let’s see about discouraging these Flemish fellows, shall we?’

I humbly pray that whomsoever wishes to read these parchments in the years to come shall indeed be able to do so, for in parts my falling tears have caused the black ink to run and the words to mingle together on the page. I am not a lachrymose man, I believe, but this tale is filled with so much sorrow that it would make the angels weep – yet also laugh, perhaps, and maybe even rejoice in the courage, strength and resourcefulness of mortal men. The words contained herein are not my own, they have flown to me straight from the mouth of Brother Alan, one of our most venerable monks here at Newstead Priory, and it has been my task to copy them down as faithfully as I am able.

Brother Alan is too frail now to write himself. Indeed, he is very close to death and spends nearly all his days in his cell, wrapped in blankets and furs, despite the first warm breath of spring in the air. And yet his mind is still clear and his memory sharp. Some might argue that this task is beneath my dignity – I am after all the Prior of Newstead, in the county of Nottinghamshire, and lord of a community of a dozen monks and a score of lay workers and servants – but Christ taught humility and Brother Alan was the man who taught me my letters when I first came to this House of God nearly ten years ago. I have never forgotten his kindness and now that I have been elevated above my fellows, I shall endeavour to make some repayment of that debt.

Christ also taught us to hate the lie – and I must not pretend that I undertake this task solely from piety and gratitude. Brother Alan’s past as a knight, as one of the most renowned fighting men of his day, and the stories he tells of battle and bloodshed, of comradeship in combat, give me a thrill of pleasure that is not entirely godly. Yet I believe I am doing God’s work in recording his story, for it sheds light upon the last years of the reign of King John and the accession of our beloved Henry of Winchester, his son and, by the grace of God in this blessed year twelve hundred and forty-six, our sovereign lord and King – long may he reign over us.

This work also aims to reveal the stark truth about the crimes and contributions of another great man, one who was Brother Alan’s friend and comrade for many years, about whom much has been said and sung, and most of that false, up and down the land. To expose these lies and calumnies – that is God’s work, indeed; as it is to reveal the true nature of this strange man, the rebel baron who fought for an evil King, the former outlaw who used the law to bring justice to the land, the unrepentant murderer and thief, the loving father and loyal husband, the friend of the poor and champion of the oppressed. It is the Lord’s will, I do earnestly believe, that the whole truth shall be known at last about the man called Robin Hood.

I fear, my dear Prior, that I have begun my tale in the wrong place. My mind is not what it was, I am old and I become easily confused these days, and my tales of blood and glory stray from their proper paths. I crave your indulgence for I must tell you of what occurred some weeks before the battle at Rochester Castle, else it will make no sense to you or to anyone who might read of my deeds and those of my comrades in the years to come.

As you well know, my dear Anthony, I have spent many hours in the past few days studying the Bible, and I find much comfort there. Robin would have scoffed at my new-found piety in the face of death but it is not salvation I seek – that I leave in the hands of a merciful God – but wisdom. There is much to be found in the holy book. I am reading Ecclesiastes and that wise old man wrote, if I have managed to untangle the Latin correctly, that there is a time for everything, a season for every activity under Heaven; there is a time to be born and a time to die; a time to plant and a time to uproot; a time to kill and a time to heal …

I was healing that August of the year of Our Lord twelve hundred and fifteen, a little slowly but surely, from a painful wound to the waist I had taken in a short, bloody fight on the walls of London that June. England, too, it seemed, was slowly healing after the struggle between the rebellious barons and the King. After Runnymede, I had dared to hope that all would be well in the kingdom for the rest of my life. That peace would reign in the land and folk would be left to sow and reap, to live, love and raise children.

A vain hope, it must now appear, but honestly held.

It was also the time to uproot, or at least to cut the barley, rye, oats and wheat that had grown tall and bright in the fields around and about my manor of Westbury in Nottinghamshire. That summer was a blazing, golden joy, long days of sunshine with only the occasional growling of a distant thunderstorm to remind us that the Heavenly Kingdom was not, in truth, at hand. All the menfolk of Westbury – my tenants from the village, the manor servants and the few freemen, old soldiers for the most part – were in their strips of field, backs bent and sickles in hand, as they lopped the nodding heads of grain from the stalks before the women following gathered them in bundles and stacked them to dry. All the local children came behind their parents, collecting the kernels of grain that spilled from the flashing blades and tucking them safely in their pouches before the wheeling flocks of birds could settle and gorge. The little ones made a game of their labours as often as not, chasing each other and shrieking with mirth. It would be a bountiful harvest, all were agreed, and if the weather continued to favour us there would be no fear of hunger or hardship till the following spring at least.

I confess I was not labouring in the fields with the other men. I was nursing my wound by drowsing in the strong afternoon sunshine, slumped on a comfortable bench outside my hall in the courtyard of Westbury, a jug of ale at my elbow, my belly full of venison stew and a blissful contentment suffusing my frame, when I heard the trumpet sound. I jerked upright fully awake – for while England might appear to be at peace, I still kept a pair of sentries day and night on the roof of the squat stone tower in the courtyard, which was the manor’s highest point and its last refuge in war, and their duty it was to warn of the approach of strangers.

Standing, straightening my clothing, brushing at a patch of drool on my tunic and vaguely looking around for my sword – it was hanging on the wall in my bedchamber, I remembered – I heard the sentry call down to me from the tower.

‘A woman, sir, all alone. No horse, nor baggage. Looks like a beggarly type wanting a free meal.’

My elderly steward Baldwin, who with his unmarried sister Alice ran the daily business of the manor, was by my shoulder. He lifted an eyebrow. ‘Sir Alan?’ he said.

‘Let her in, Baldwin,’ I said, still filled with a glowing benevolence for the world. ‘If she needs a meal, give her a good one and whatever scraps of meat and bread we can spare for her journeying and then send her on her way.’

‘As you say, sir.’

‘I’m going to my solar to take a little n— That is to say, I shall retire to my chamber for a while to study my scrolls.’

I left the glare of the sunshine and pushed past Baldwin into the gloom of the hall. I gave no more thought to the beggar woman, for as I entered my solar at the far end and lay down on the big, comfortable bed, I fell into a deep and delightful sleep.

I awoke in the pinkish twilight of the long summer evening, refreshed and still brimming with contentment, and lay for a while listening to the sounds of the servants clattering plates in the hall, no doubt preparing the evening meal. I could hear the voice of my fifteen-year-old son Robert but I could not quite make out his words over the noise of the hall servants. He seemed animated, though, unusually cheerful, and I wondered who he was talking to. And then I heard her voice.

I sat up abruptly and an icy chill puckered the skin of my forearms. I was out the door of the solar in an instant – and there she was. Seated at the big hall table a few feet from Robert, elbows on the board, deep in conversation.

‘Get away from her!’ I bawled, running towards my son and the beggar woman. They both started to their feet, shocked.

‘Robert, get away from that woman right now.’

‘Why, Father, we were—’

‘Get away. Come and stand behind me.’

My heart was racing, I could feel my face and neck hot with surging blood. I curled a protective arm around Robert. ‘Did she feed you anything? Robert – did she give you anything to eat or drink?’

‘Father, you are behaving in a very—’

‘Answer me. Did she give you anything to eat or touch your skin?’

‘Father …’ My son looked into my face and saw that I was in deadly earnest. ‘She gave me nothing. She did not touch me. We were waiting for you to wake before we ate. She will take supper with us tonight.’

‘She will not,’ I said. My right hand was groping wildly across my waist for my sword hilt but, of course, the blade was still hanging on the wall in the bedchamber. I looked at the woman, now smiling crookedly at me from the other side of the table.

‘Sir Alan,’ said Matilda Giffard in her wood-smoke-deepened voice, ‘what a joy it is to set eyes on you again.’

‘I cannot say the same,’ I said coldly.

I looked at her. Matilda Giffard, Tilda, as she was to me … a woman I had once – no, twice – thought I was in love with but who had proved herself as treacherous and cunning as a starving rat.

She had once been a great beauty – a woman to stop a man’s heart – but on this day, although her looks had not entirely deserted her, she cut a poor figure: she was thin as a twig and dressed in a raggedy black nun’s robe, greyed by the dust of the road. Her once swan-white face was decidedly grubby, she had the remains of a black eye, now faded to streaks of brown and yellow, and the lines on her brow beneath her midnight black hair and around her grey-blue eyes were cut deeper than I remembered.

‘My dear, you have nothing to fear from me, I swear it,’ said Tilda, smiling. Her familiar voice sent ripples running down my spine.

She stepped away from the table and came towards me. With difficulty, I managed not to take a step backwards, and pulled Robert tighter to my side.

‘I do not fear you,’ I said, lying once more.

‘That is as it should be. I know that we had harsh words when we last met. And you cannot know how much I regret them—’

‘I do not fear you,’ I cut her off, ‘I merely ask that you leave my hall, my home and my lands immediately.’

‘I have wronged you; Robert, too. I freely admit it. But I come humbly to seek your forgiveness for my actions. I know you are a kind man—’

‘You shall not have it. You schemed to kill us. You used your wiles and my own loving foolishness to snare me. You betrayed me to my enemies. At every turn you have sought my destruction. Whatever it is that you say you require, you shall not have from my hand. I shall have no more dealings with you. Now, I must ask you to leave. This instant. Or I shall fetch my men and have you thrown from the ramparts.’

To my utter astonishment, Tilda fell to her knees in front of me. She clasped her hands before her in supplication and I swear that a succession of oily tears began to course down her dirty white cheeks.

‘Sir Alan, I beg you. It was so hard for me to come here. Forgive me. Dear God, I ask you in all humility. Show me mercy. Forgive me and grant me sanctuary. I have nowhere else to turn. In the name of the love you once professed, forgive me. I beg you.’

I was utterly at a loss. I had seen Tilda merry, fearful, sad and scornful, even spitting bile-bitter hatred at me. But I’d never seen her like this. So … broken. So stripped of dignity. Pleading for my forgiveness on her knees. My heart twisted in pity.

‘Go back to Kirklees. Go back home to the Priory, woman, and do not trouble us again. You shall have food. An armed escort, if you want it. But you will not stay here.’

‘I cannot,’ she said. Tilda was sobbing without restraint. She buried her face in her hands and her words came out jerkily, muffled and odd sounding.

‘Expelled. The mother Prioress. Anna. She and I, we … She threw me out. I have nowhere to go. I have no place. I am lost.’

A weeping woman on her knees is a hard thing for a man to witness, particularly if she was once his lover. But I knew Tilda of old and, while her grief did seem genuine, I could not bring myself to trust her once again. I hardened my heart and called for help.

‘Baldwin,’ I said to my steward, who was hovering by the table with his mouth open in shock. ‘Fetch the lady a satchel of food, a flask of wine and a warm cloak, and escort her from the manor. If she will not go, get Hal and some of the men-at-arms to help you. Robert and I will be in my solar. Report to me when she is gone.’

I turned my back on the sobbing woman on her knees in the hall and, half-pushing Robert to force him along, I stalked back to my chamber.

Inside, with the door closed and my weight leaning securely against it, I felt my heart pounding as if I had run a mile in full armour.

‘I do think that was rather harsh, Father,’ said Robert.

I had thought I was rid of Tilda once and for all but life is never that simple. Baldwin reported that he had provided her with food and drink and a cloak and escorted her – she was meek as a lamb, he said – out of the main gate. He had stayed to watch her set out on the road towards Nottingham but after only a few hundred yards she had veered off the track headed towards the river and had collapsed down under a willow tree on the bank, a huddle of misery, still within a half-mile of my gates.

‘Do you wish me to send the men-at-arms to roust her?’ Baldwin asked.

‘No,’ I said. It was dark by then and to send a troop of mounted men to move along one tearful middle-aged woman seemed excessively cruel. ‘Let her sleep the night there in peace. Doubtless she will be gone in the morning.’

She wasn’t, of course.

The next morning, from the roof of my tower, I could clearly see her, a black shape under the willow tree, still as a stone. It crossed my mind to order out the men-at-arms then, and have them move her on with their spear butts, but I had not the heart for it. I contented myself with issuing stern orders to all the servants that Matilda Giffard must not be allowed to set so much as a toe within my walls again.

We were very busy over the next few days with the harvest and, while I cannot pretend that Tilda disappeared from my mind completely – she hovered constantly on the fringes of my thoughts like an unpaid debt – I did manage to banish her from my daily processes. I ignored her, in truth. She stayed by the willow tree day after day, moving very seldom, at least in daylight, troubling nobody as far as I could tell and slowly, almost imperceptibly, becoming absorbed into the landscape of Westbury.

Four days after the tearful scene in the hall, Robin arrived.

My lord came apparelled for war and with two score mounted men-at-arms at his back. He was in high spirits, oddly, for the news he bore was almost all bad. Over a cup of wine in my hall, he informed me that the King had reneged on the promises given at Runnymede and that we were summoned once more to war by Lord Fitzwalter and the Army of God. I confess my heart sank at the news.

‘We knew it couldn’t last, Alan,’ said my lord. ‘When has King John ever kept a promise, let alone one extracted at the point of a sword?’

He made a good argument: John was one of the most duplicitous men I have ever had the misfortune to encounter, indeed the bitter hatred felt for him by the barons of England had much to do with his untrustworthiness, but my dreams of a peaceful existence had been scattered to the winds by Robin’s arrival.

‘I need you, Sir Alan,’ he said. ‘I need your sword once mor

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...