- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

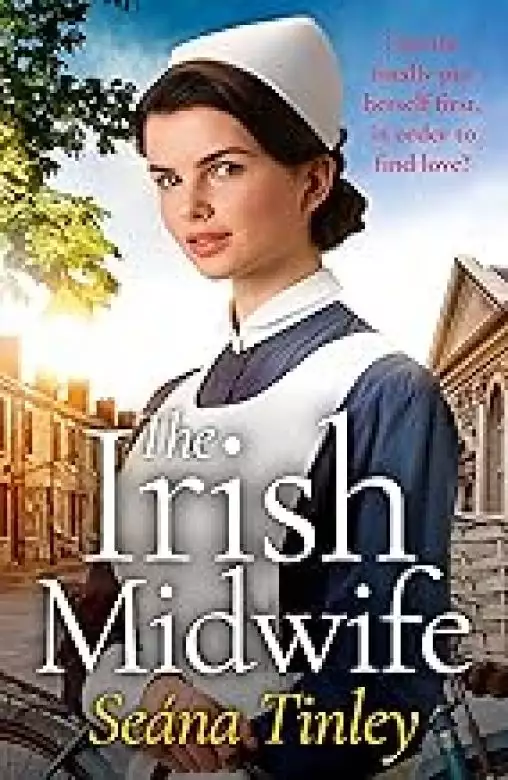

Synopsis

Peggy Cassidy is a milly, working in the Belfast linen mills alongside her family to just about get by. But Peggy has another job - a secret one. She also works alongside her beloved Aunt Bridget as a handywoman - an illegal midwife, tending to the women of her community in their time of need. When her Aunt Bridget is arrested while they are supporting a local woman giving birth, it sets off a chain of events that will change Peggy's life forever.

Leaving Belfast and her family for the first time, Peggy instead heads to Dublin, where she will train as a proper midwife. There, Peggy can't quite believe the luxuries of her new life - plenty of food, a fine uniform, new friends, and maybe even the chance to fall in love...

But Peggy must keep the truth about her family - and especially, her own past as a handywoman - secret at all times. And when the realities of her life in Belfast - the realities of who she really is - are revealed, will she lose everything she has worked towards?

And will she choose to protect her family, rather than let herself fall in love?

Release date: September 11, 2025

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Irish Midwife

Seána Tinley

Belfast, Thursday, 31 January 1935

The day Peggy Cassidy’s life changed forever began with the birth of a baby. At the ripe old age of sixteen – nearly seventeen – she had seen almost a hundred babies born, and every single birth had been unique.

‘The baby’s coming!’

There was fear in Mrs Murray’s voice – fear that could be a problem. Thankfully, Peggy could see the baby’s head descending in a perfectly normal way.

‘Yes, it is,’ she said soothingly. ‘It’s all right, Mrs Murray. You’re doing a great job, so you are.’

Thankfully, this seemed to settle Mrs Murray. Occasionally, first-time mothers would get themselves in a panic, which could make the birth slow down. Behind her, she could hear Aunty Bridget getting ready for the baby. Mrs Murray had provided clean, soft towels, a wee vest, and some terry nappies, and it was clear they would be needed very, very soon. The most important thing she and Aunty Bridget could do now was to help Mrs Murray stay calm and focused.

Taking a thin piece of wool from her pocket, Peggy tied back her long, dark hair in readiness for the birth. The last thing she wanted was for her own unruly curls to get in the way.

‘Now, another pain is coming in a minute, and you’ll feel yourself pushing again, Mrs Murray. Are you comfortable the way you are, or do you want to get onto your knees?’

‘Can I?’ Mrs Murray looked red-faced and tired, but the labour had only been going on since late yesterday, so Peggy knew she would still have good reserves of strength. First babies could be slow to come. A quick glance towards the window told her it was now almost morning, weak light penetrating the thin curtain. The January nights had seemed endless, reluctantly giving way to allow a few minutes of extra daylight each day.

With Aunty Bridget’s help, she supported Mrs Murray to flip onto her knees and grip the wooden headboard of her sturdy bed. And not a moment too soon, for she was pushing again – loud, guttural groans coming from her throat. Peggy and Aunty Bridget’s eyes met – the same eyes, for Peggy had inherited the Doyle blue eyes from her ma. A sense of connection, of shared purpose, flowed through her. This was important work, and she and Aunty Bridget were doing it together. Soon all the hours of patient waiting would be done.

Together Peggy and her aunt arranged towels on the bed between the woman’s knees, ready to receive the baby. Sensibly, Mrs Murray had covered her mattress with a rubber sheet before making it up with cool cotton bed linen. The bed was normally pushed up against the wall of the small bedroom, but with Mrs Murray’s agreement Peggy and Aunty Bridget had pulled it out when they arrived yesterday, to allow them to get around both sides of it.

There was a discreet knocking on the door, which Peggy ignored. Once Mrs Murray’s contraction had eased though, she left Aunty Bridget murmuring soothing words to Mrs Murray and went over to open it a crack.

As expected, it was Mr Murray, his face pale and his brow furrowed. ‘How is she? I can hear her from downstairs.’

‘She’s fine. It won’t be long now. Can we have some more hot water?’

‘Yes, of course.’ He disappeared speedily, and Peggy suppressed a smile. Some of the men would go to the pub during the evening, but once they were back in the house they often needed to be given jobs to do. Besides, she and Aunty Bridget were sticklers for hygiene, and washed their hands with soap and a nail brush on a regular basis while attending a birth, so the hot water was genuinely needed. Mr Murray had been taken for pints by the menfolk yesterday evening, but had spent the night downstairs with his wife’s mother and sisters, as well as his own ma. Peggy had heard the reassuring hum of conversation from downstairs through the night, and knew Mrs Murray would have been comforted by it, too. Sometimes a woman would want her own mammy in the room, which was fine, but more often than not she was content just to have the handywomen.

Having a baby, Aunty Bridget always said, was the most natural thing in the world, but that didn’t mean it should be ignored or taken for granted. A new member of the Murray family was about to come into the world, and the significance for the whole family could not be overstated.

And I am to be part of it! Peggy thought. It never grew old – the feeling of privilege that, in her role as trainee handywoman, she got to be part of special moments for so many women. The numbers she had supported were nothing, of course, not in comparison to Aunty Bridget’s experience. For more than forty years Bridget Devine had served the women of West Belfast and as a result, she was held in high esteem throughout the community. All the handywomen were.

Not that there were that many of them. Peggy knew of only four in the west – Aunty Bridget and her great friend Mrs Clarke, as well as Mrs Kennedy and Mrs Quinn. That was why Aunty Bridget was training Peggy, for they knew there would always be a need for five or six handywomen for their sprawling community based around Belfast’s Falls Road. Apparently there had been more handywomen needed at one time, but more recently wealthier women were choosing to pay doctors’ fees and have their babies in hospitals and maternity homes. Not so the working women of West. While emergency care was free, they wouldn’t have the money to pay for a doctor every time they had a baby.

Not that doctors were needed, anyway. Not for straightforward births, which most births were. That was women’s business. The business of the women and the handywomen.

Mrs Murray began groaning again, and Peggy nodded in satisfaction. The pains were coming one after another, which would hopefully prevent the baby’s head from slipping back up the birth canal.

About ten minutes later the head was out. Peggy watched as it moved – a full quarter turn to align with its shoulders. It was fascinating how that happened, every time. Gently, Aunty Bridget checked the cord, and Peggy saw her frown.

‘Try not to push for a minute, Mrs Murray,’ she said, and Peggy saw that the cord was wrapped tightly around the baby’s neck. She held her breath as Aunty Bridget worked at it, trying to resist the instinct to be worried. Babies don’t breathe the way we do, she reminded herself. Before birth they got their oxygen directly from the blood in the cord, so the only problem would be if the cord was nipped so much it wasn’t able to pulse into the baby. Peering closely, she saw that the cord was a healthy colour, plump and purple.

Aunty Bridget’s clever hands, spotted with age and wisdom, were working deftly to release the cord, and a moment later Peggy saw her slip it over the baby’s head. Peggy watched closely, as she’d only seen it done a couple of times, but as before, there was no issue. The cord was still a good colour, its natural springiness ensuring the blood had kept flowing to the baby.

It struck her then that she knew things – that she was genuinely learning from Aunty Bridget. Well, and why wouldn’t she? She’d been helping with births – and with laying out the dead – since leaving school at fourteen.

Nearly three years of it, being sent for after working her shifts in the mill, on her days off, or on Sundays when the mill was closed. She hated being a milly – as the Belfast mill-girls were called – and couldn’t wait to work as a handywoman full-time. She even got paid a bit already, if there was enough money. Sometimes the women paid Aunty Bridget in favours or food, because they couldn’t afford her modest fee. It didn’t matter, for Bridget Devine would help anyway, and everyone in West Belfast knew it.

‘Now then, Mrs Murray, it’s time. With the next push, your baby might be here.’

Mrs Murray nodded, then the urge to push took her over again. A moment later the baby was out, landing squarely on the towels. Its colour was good, the cord was beating healthily, and within seconds it began to cry.

‘Move this leg . . . now turn . . . that’s it.’ Aunty Bridget directed Mrs Murray to turn around safely, then helped her pick up her baby. ‘A wee boy. Maith thú. Well done!’ Aunty Bridget still spoke Irish occasionally, particularly when emotional.

‘Oh, oh, my baby! I can’t believe it!’ Mrs Murray was holding him close, rubbing his wee head and back. ‘Look at that head of hair! Look at his wee hands!’

‘And a good size too, Mrs Murray. I’d guess he’s a seven-pounder.’ Aunty Bridget was covering his wee back with towels – it wasn’t good for newborn babies to get cold. Peggy congratulated the new mother then added coal to the fire. Mrs Murray’s house was identical to her own, and the fireplace in the upstairs front bedroom of these houses rarely got used. Now that the baby was born, the room needed to be a lot warmer.

Knowing that Mr Murray was probably on the landing, she opened the door again, a little. There he was, along with his mother, Mrs Murray’s mother, and three of her sisters. ‘All well,’ she said. ‘A boy. We just need a wee while longer. And bring us that bucket, please.’ She sent a meaningful look to the women crowding the narrow landing.

‘Ah, that’s great. Right, everybody! Downstairs. Time to put the kettle on.’ Mrs Murray senior was taking everybody in hand. Still smiling, Peggy closed the door and went back to the new mother, who was already undoing the buttons at the top of her nightdress.

‘My ma told me to feed the baby straight away, so she did.’

‘And she was right!’ Aunty Bridget agreed. ‘But let him do it himself. Here, let me fix these pillows.’ She arranged the pillows so that Mrs Murray was still sitting, but slightly laid back. ‘There. Now you can be comfortable, love.’

Peggy was keeping an eye on Mrs Murray’s bleeding. A steady trickle, nothing major. And only the tiniest tear, thankfully. Leaving Mrs Murray to coo at her baby, she and her aunt tidied the room. One of the women brought the bucket – and in the nick of time, for Mrs Murray was groaning again, as the afterbirth announced its imminent arrival.

Peggy took the baby, checking that the cord had finished its work. Sure enough, it was now white and limp – a strong contrast to the purple pulsating of twenty minutes ago. Tying it off in two places with strong wool, she cut between them with scissors cleaned in the freshly boiled water, then took the baby to the foot of the bed to dress him in nappy, wool pants, and vest. The afterbirth was now out, so the baby went directly back to his mammy, wrapped in a wee knitted blanket, while Aunty Bridget inspected the afterbirth before carefully placing it in the bucket.

‘That’s us now,’ she declared with an air of satisfaction, the familiar words delivered in an accent that was pure Belfast. At’s us nai.

And it was. Another baby safely born. Another contented mother holding her wee one close.

Another good day.

2

‘Are you ready to show him off?’

The baby had had his first feed and all was well. Mrs Murray, beaming, agreed and Peggy left the room, closing the door behind her. This was such a lovely part of her role, inviting the new father and the grannies in to see the wee one.

A minute later Mr Murray was bounding up the stairs, followed in a much more dignified manner by both grannies, who were even now sharing an indulgent look and rolling their eyes. Peggy grinned, relief and exhilaration coursing through her. Tragedies did still happen during childbirth – no one knew why sometimes – though they were rare. Still, it was always comforting to get to this point, with baby safely out and mammy and baby doing well.

As the women passed her on the landing, Mrs Murray’s mother told Peggy to go to the kitchen, where some fresh toast and a cuppa tae were awaiting her. She needed no second bidding, and a few moments later Aunty Bridget joined her. They had eaten nothing since yesterday teatime, and the toast was all the nicer for it. Mrs Murray’s ma had taken tea and toast upstairs for the new mother, who would be even more ravenous.

They sat chatting idly, warmth coursing through Peggy at the knowledge that all was well. How many times had they done this – sitting in a kitchen after a birth? Night or day, the routine was the same – tea, toast, and a sense of satisfaction.

‘You done well, Peggy,’ said Aunty Bridget, popping the last morsel of toast into her mouth. ‘You’ll make a fine handywoman, so you will.’

The warmth flooding through Peggy at her aunt’s compliment made her smile.

‘Ach sure, I’m only learning.’

‘Another six months or so and you’ll be ready to go to births on your own.’

Peggy’s eyes widened. ‘Really?’

‘Aye. You’re a good girl, Peggy. And a great learner.’

Peggy blushed and stammered. Around here, people didn’t usually say nice things so openly.

‘Don’t you be getting all mortified now, Peggy.’ Aunty Bridget’s tone was firm. ‘You’re like a daughter to me, and that’s a fact.’

It was true, but Aunty Bridget had never said it out loud before. Her husband had died before Peggy was born – a hero of the Easter Rising – and Aunty Bridget had never remarried. Her nieces and nephews all adored her, but Peggy had often wondered if Aunty Bridget had a soft spot for her. After all, she had been the one selected to train as a handywoman alongside her aunt. The deal had been done between Ma and Aunty Bridget, and Peggy had been delighted when they had told her of it.

‘I know,’ she said softly. ‘I’m lucky enough to have two mammies – although that does mean double the telling-off sometimes!’

Bridget laughed, throwing her head back and guffawing the way she did sometimes. Affection coursed through Peggy at the sight. Aunty Bridget’s hair was grey now, her face increasingly wrinkled. But she was one of the most alive people Peggy knew. It was probably because she had managed to avoid a lifetime in the mills. Mill-hands died young – mostly of accidents or lung diseases. The handywoman’s other job was sitting with the dying, and Peggy could recall nights trying to comfort frightened people struggling to get a breath. It was not a good way to die.

Thank God Bridget was unlikely ever to suffer that way, but Peggy worried about the rest of them – Da, who worked long hours in the mill, and Peggy’s brothers and sisters along with him. Ma had escaped because she needed to be a mother instead, and Granda was too old to work now, but Gerard, Antoinette and Sheila all worked full-time as mill-hands. The wee ones – Joe and Aiveen – were too young yet, but their time would come, too. Every penny of wages was needed to cover food and rent. Peggy was lucky the family had taken the hit of her staying a half-timer so she could train as a handywoman.

‘Aye, well sometimes you need a good telling-off, my girl – though to be fair it’s only a now-and-again thing. I recall my own ma – your Granny Doyle – was a fierce woman. I used to dread her shouting at me!’

‘Aye, I remember she was a strong woman.’

‘We all are, Peggy – all us Doyle women.’ Aunty Bridget leaned forward, her blue eyes pinning Peggy’s. ‘You might be called Cassidy but you’re a true Doyle, and never you forget it!’

‘I—’

Abruptly, there was a pounding at the front door. Peggy and Aunty Bridget looked at each other, both rising and making for the living room. Peggy’s inner sense of satisfaction was giving way to fear. Who would make that racket in a house where everyone knew there was a woman having a baby? God, was somebody not well? She bit her lip.

‘Open up! Police!’ The voice was loud, demanding, and utterly terrifying.

What in God’s name did the police want?

3

The pounding on the door was continuing, louder than before.

‘Jesus, Mary and Joseph!’ Aunty Bridget made the sign of the cross then stepped forward – just as Mr Murray’s ma reached the bottom of the stairs and opened the front door.

Immediately the house was invaded. Two burly men, both wearing the insignia of the dreaded Royal Ulster Constabulary. One headed straight upstairs, while the other came into the living room. Peggy’s heart was thumping like a hammer in her chest, and her palms were suddenly sweaty with fear. What do they want?

The RUC constable was tall and broad, with a red face and a cross expression. He looked at them all, his eyes narrowed. ‘Mrs Bridget Devine?’

Cold fear pooled in Peggy’s stomach. She clutched her aunt’s arm, feeling the tension in her.

Aunty Bridget straightened. ‘I am Mrs Devine. Why?’

‘We have reason to believe that you are practising midwifery without a licence. There have been complaints.’

Peggy gasped. Aunty Bridget was highly respected in the community. Who on earth would complain about her? She moved forward, leaning against Aunty Bridget from behind. I am here.

Bridget straightened. ‘Complaints from whom?’

‘Not one but two doctors.’ He consulted his notebook. ‘Dr Fenton and Dr Sheridan. They say you’re putting lives at risk.’

At this, Peggy felt her sag slightly. Aunty Bridget saved lives! Never would she do anything risky with the women who trusted her.

‘Dr Fenton,’ Aunty Bridget mused, shaking her head. ‘But I’m surprised about Dr Sheridan. I thought he was better than this.’ She turned to Peggy, her face pale but her voice remarkably steady.

‘Peggy,’ she murmured, ‘tell your ma not to fight this.’ She looked her in the eye. ‘Will you do that for me?’

‘But—’ Peggy could barely contain her outrage, her terror on Aunty Bridget’s behalf. The community could have a crowd outside the police station in no time if needed. There would certainly be anger enough.

How dared the police challenge Bridget Devine née Doyle – a woman who was well known and well respected, and who had never broken a law in her life! Or at least, had never broken a sensible law.

‘Will you do that for me?’ Aunty Bridget’s look was intent, and Peggy nodded.

‘And who is this?’ The policeman was now looking at her, his expression disdainful. ‘Another so-called handywoman?’

‘She’s nobody. My sister’s girl.’

‘You wouldn’t be training her up, now would you?’

Peggy could feel the blood draining from her face, but Aunty Bridget was well fit for them. She laughed – actually laughed, saying, ‘Sure she’s only a chile.’

Just then, his colleague reappeared. ‘New baby and mother upstairs. Our information from the pub was correct. She swears she had it alone, but’ – he jerked his head towards Bridget – ‘you got her?’

‘I have indeed. Right, come with us, please.’ He stepped back, indicating that Aunty Bridget should pass him. Helplessly Peggy watched, noticing in that moment that Aunty Bridget was walking confidently, head held high. The sight of her grey hair secured in its usual neat bun seemed incongruous, somehow. Were the RUC really lifting her aunt? A woman who had recently turned sixty? And for what? For helping other women? Rage blazed through her. How feckin’ dare they!

Outside a crowd was gathering, as it always did when the RUC came into their tight-knit community.

‘On yiz go, yiz bastards!’ shouted one elderly man, and a chorus of jeers echoed out.

‘Leave the Murrays alone!’ shouted a woman. ‘They’re good people!’

Peggy could almost feel the moment when the crowd realised what was going on. A wave of gasps and shocked exclamations rippled through the crowd, with people exclaiming:

‘It’s Mrs Devine!’

‘No!’

‘Oh my God!’

‘Leave her alone!’

‘What the hell are you doing with Mrs Devine?’

Stony-faced, the police ignored them, putting Aunty Bridget into the back of the police car, then climbing in the front.

Oh, poor Aunty Bridget!

As the motor car moved off some of the young lads ran after it, hurling insults until it turned the corner and was gone. Peggy, tears rolling down her cheeks, could only stand there, entirely helpless.

4

‘So where did they take you?’

Peggy watched silently as her ma questioned Aunty Bridget about her ordeal. It was midnight and Aunty Bridget had finally reappeared in her tiny house, one street down from Peggy’s home. It was the house Bridget and Peggy’s mammy had grown up in. After the Rising, when the news had come of her husband’s death, Aunty Bridget – widowed and childless – had moved back into her home house with her ageing mother. With never a complaint about the hand that fate had dealt her, she had looked after her elderly mother until Granny Doyle’s death. And now this. It was so unfair!

Following hugs, and the kettle going back on, Aunty Bridget was now sitting in her own armchair by her own fire, answering Ma’s questions.

‘The main police station – the one where the Andersonstown Road meets the Glen Road, you know?’

‘And you walked home? In the dark? At midnight?’

‘And sure why wouldn’t I? I know all these streets and everybody that lives in them!’ Aunty Bridget chuckled. ‘It takes more than intimidation from a few eejits to properly scare me – though I have to admit it was a shock when they landed into Mrs Murray’s house. Is she all right?’ Her gaze swung to Peggy, who nodded. ‘And the baby? Good. Absolutely disgraceful carry-on, invading the home of a woman giving birth.’

Ma shrugged. ‘It’s the RUC. What else do you expect from a pig but a grunt?’

‘Ah, now,’ said Aunty Bridget. ‘Don’t you be giving pigs a bad name, Mary!’ They laughed then – laughter that held a great deal of relief. Despite her light-hearted words, Peggy could see strain in the lines of Aunty Bridget’s face. It was as if she had aged twenty years since this morning.

‘Did they formally arrest you, Bridget?’

‘Aye, but it’s nothing to worry about, Mary.’

‘Nothing to worry about? You could be put in prison!’

Bridget shrugged. ‘It’s not as simple as that.’

Ma’s brow was furrowed. ‘I don’t follow you.’

‘They brought in a law to say only midwives and doctors can attend births. They’ve made it a crime all right, but the punishment for handywomen who get caught is a fine, not prison. The whole “you’re under arrest” play-acting was only to intimidate me.’

‘How much of a fine?’

Aunty Bridget grimaced. ‘Ten pounds.’

Ma blessed herself. ‘How are you supposed to find that sort of money? It’s a fortune!’

Aunty Bridget’s eyes danced with mischief. ‘I have a good wee bit put by, but damn sures they’re not getting it!’

Mammy looked puzzled. ‘Then what—’

‘They can put me in prison as a debtor, I suppose . . . but they’re still not getting my savings.’

‘Now, Bridget—’

‘Don’t you now, Bridget me, Mary! I would remind you that I am the eldest, and you the youngest. And you might be Mrs Cassidy now, but in this house you’ll always be Mary Doyle, the baby of the family!’ She pursed her lips. ‘I haven’t been working for forty-five years just so the RUC and a couple of big doctors with notions about themselves can steal it from me!’

‘Yeah, who were the doctors who reported you? Do you know them?’

‘I do.’ Aunty Bridget nodded briskly – as though they weren’t discussing the fact she had been detained in a police cell all day. ‘Fenton is a big-shot in the Royal. Thinks he is somebody. Doesn’t surprise me in the least that he did this.’ She paused. ‘Dr Sheridan though . . .’ Her face twisted and Peggy suddenly realised that Aunty Bridget looked hurt. ‘He’s a general practitioner in South Belfast. I never had much to do with him, for he has very few patients here in West. But he always struck me as a good man. Fair, you know?’ Her eyes became unfocused. ‘Just shows you, you never really know anybody, do you?’

‘Ah, this is a disaster.’ Ma’s hand was on her forehead. ‘We’ll talk about it in the morning. Peggy, you’ll stay here tonight.’

Peggy nodded, even as Aunty Bridget protested that she didn’t need a babysitter and Ma overruled her with all the authority of a mother of six.

‘She’s staying, and that’s final.’ She turned to Peggy. ‘You’ll miss work tomorrow – our Antoinette can tell them you’re sick. She can pick up your wages too.’

‘But that’ll mean less money this week. Will we manage?’

Ma looked after all the money in the family, everybody including Daddy dutifully handing over their wages every Friday.

Ma shrugged. ‘We manage when you’re at a birth or a wake. We’ll manage this week.’ Her tone was firm. ‘Now, go and fill a hot-water bottle for your aunty Bridget, for it’s freezin’ tonight.’

Peggy complied, and she was upstairs putting the rubber bottle into Aunty Bridget’s bed when she heard a shriek from below. ‘Peggy! Come quick!’

Hurrying down the stairs, her heart pounding at the fear in Ma’s voice, she dashed into the wee living room. Aunty Bridget was slumped in her chair, one side of her face sagging, and Ma kneeling beside her.

‘It’s all right, Bridget,’ she was saying softly. She turned to Peggy. ‘Go and get Dr Gaffney, quick!’

Peggy didn’t need to be told twice. Grabbing her coat, she ran out the door, heading down to the bottom of Rockdale Street and turning right, passing her own street, Rockville, then Rockmore Road and Rockmount Street. The ‘Rock streets’ as they were known, for obvious reasons. Those who lived here had a tight-knit sense of community.

Peggy knew exactly which house to go to – the big house on the Falls Road beside the chapel. In her three years helping Aunty Bridget, she had been sent for the doctor a few times – for a woman who had a fever, a woman who bled, a woman whose baby wouldn’t come. Dr Gaffney had come, and each time he had arranged for an ambulance, and praised Aunty Bridget for doing the right thing. Emergency care was free, unlike hiring a doctor or midwife. The women and babies had been fine afterwards, thank God. Dr Gaffney, she knew, would never have dreamed of complaining about a handywoman.

As she ran, under her breath she was muttering a decade of the rosary. First, an Our Father, then ten Hail Marys . . . And all the while she was wishing, praying, begging for a miracle.

Aunty Bridget’s house in Rockdale Street was identical to the Cassidy family home one street over. Living room to the front, kitchen to the back, with an outhouse in the backyard. There was running water for the kitchen sink as well as electric lights and even two power sockets. Upstairs were two bedrooms, usually stuffed full of people. At home Granda Joe (who was Da’s da) and Peggy’s brothers Gerard and wee Joe shared the back bedroom, while Peggy shared the front bedroom with her sisters Antoinette, Sheila, and wee Aiveen. Ma and Da slept downstairs on a big mattress that got hauled upstairs every morning. Still, Antoinette and Gerard were both courting and saving to get married, so in a few years the house would be a bit emptier, with two of the six children up and away.

Because Aunty Bridget lived by herself in Granny and Granda Doyle’s old house, that meant there was usually at least one of the Cassidys or their cousins staying over in her back bedroom. Her two-up two-down seemed enormous for just one person. Tonight it would be Peggy’s turn to stay over – especially with poor Aunty Bridget not being well.

Dr Gaffney had come, confirmed it was a stroke, had shaken his head sadly, and left again. Da had been sent for, to carry his sister-in-law up to her bed, where Ma and Peggy had made her comfortable. By morning she was opening her eyes, and even talking – her speech slurred and hard to make out at times. She kept having nosebleeds and was complaining of a bad headache. Dr Gaffney had said Aunty Bridget’s blood pressure was very high and had warned she might have a second stroke. Peggy had only a vague idea what blood pressure was, but Dr Gaffney’s demeanour told her everything she needed to know. He was deeply concerned.

Peggy, used to sitting through the night with women in labour, had made Ma go to the back bedroom to sleep a few hours ago, and had then taken a turn at sleeping herself, but when it got to half-five in the morning Ma came back, letting Peggy go to help Antoinette with Ma’s jobs at home.

Da was already up when she got home, the mat. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...