- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

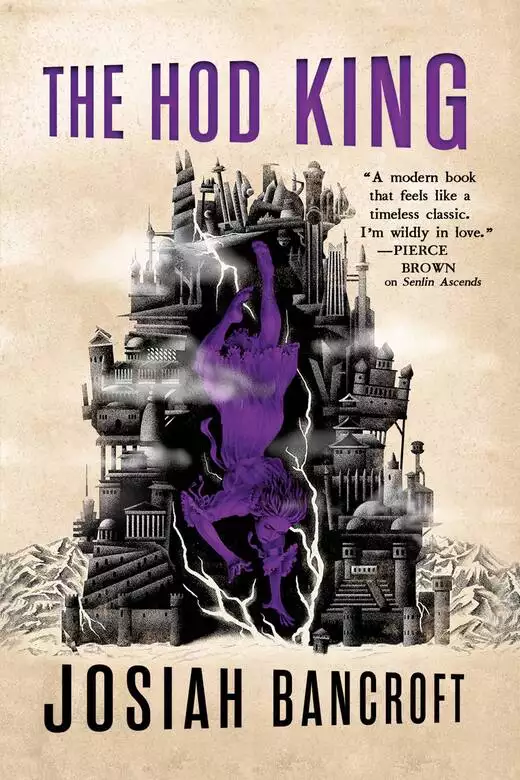

Synopsis

Thomas Senlin and his crew of outcasts have been separated, and now they must face the dangers of the labyrinthine tower on their own in this third audiobook in the word-of-mouth phenomenon fantasy series.

Fearing an uprising, the Sphinx sends Senlin to investigate a plot that has taken hold in the ringdom of Pelphia. Alone in the city, Senlin infiltrates a bloody arena where hods battle for the public's entertainment. But his investigation is quickly derailed by a gruesome crime and an unexpected reunion.

Posing as a noble lady and her handmaid, Voleta and Iren attempt to reach Marya, who is isolated by her fame. While navigating the court, Voleta attracts the unwanted attention of a powerful prince whose pursuit of her threatens their plan.

Edith, now captain of the Sphinx's fierce flagship, joins forces with a fellow wakeman to investigate the disappearance of a beloved friend. She must decide who to trust as her desperate search brings her nearer to the Black Trail where the hods climb in darkness and whisper of the Hod King. As Senlin and his crew become further dragged in to the conspiracies of the Tower, everything falls to one question: Who is The Hod King?

Release date: January 22, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Hod King

Josiah Bancroft

—Oren Robinson of the Daily Reverie

The sun clacked along an iron track among the gaslight stars high above the white city of Pelphia. The domed ceiling was a perfect shade of sky blue, except where the paint had flaked away, leaving behind jagged clouds of naked mortar. Gas flames ringed the smiling face of the mechanical sun, which left a trail of soot in its slow circuit over the city. In the evening, the sun set inside a ballroom, built to evoke a great nimbus cloud, called Horizon Hall. In addition to acting as the sun’s stable, Horizon Hall was the site of frequent and often wild galas. It wasn’t uncommon for the sun to rise late, delayed by gears that were clogged with confetti, vomit, and undergarments. And every so often, when repairs to the sun were particularly slow, Pelphia would experience an eclipse that might last two or three days. In more sophisticated ringdoms, such a span of unanticipated darkness could easily have triggered riots, if not a revolution, but in Pelphia, these protracted periods of dark were hardly remarked upon because no one wished to be the yawning party pooper who said, “It seems to have gotten terribly late, hasn’t it? Perhaps we should call it a night?”

The ringdom’s king behaved more like a court jester than a regent, and was beloved for it, much in the same way a permissive father is adored by his unruly brats. The ringdom attracted the occasional tourists from the far-flung coasts and hills of Ur, but Pelphia’s only reliable industry was the production of fabric and its transformation into high fashion. The upper ringdoms of the Tower were loath to admit that they took any cues from such an ancient and ironically juvenile ringdom, but for all their irritating histrionics, Pelphians had a knack for buttons, thread, and taffeta. It was for this reason the fifth ringdom was sometimes called the Closet.

But while the rest of the Tower only recognized the customary four seasons of fashion, the obsessed natives of Pelphia somehow managed to squeeze fifteen or sixteen seasons into a single year. The dressmakers, cobblers, haberdashers, and tailors were in constant competition, hoping to spark the next craze even as they indulged the present one. Wars were waged from the shopwindows of the most famous clothiers, until one neckline or hem or hue rose above the rest, and a new fad overwhelmed the last. Then the population would change color as quickly and uniformly as a forest in fall.

But the natives’ obsession with appearances did not extend to their streets. Pelphians were terrible litterers. The white cobbles of Pelphia were often obscured by trash. Playhouse programs, handkerchiefs, dance cards, love notes, the feeble heels of ambitious shoes, and a thousand tokens of unwanted affection overwhelmed the gutters. Early each morning, while half the city groaned through hangovers and dawning regrets, hundreds of hods emerged from alley shacks with brooms, brushes, and pots of whitewash to paint over the graffiti and lamp soot. The army of indentured cleaners blanched the ringdom from port to piazza, where the spine of the Tower rose from the city’s center like a pole in a circus tent.

Pelphia’s three most ancient institutions stood in the shadow of the ringdom’s spine: the Circuit of Court, a sprawling, winding hedge of silk and wire; the Vivant Music Hall, a cathedral that seemed as frail as a bleached reef; and the Colosseum. Once, the Colosseum had been a university, and its fat columns and carved gables still bore the evidence of that former use. Scenes of laureled philosophers and robed poets still decorated its high lintels, though the bottom halves of those women and men had been chiseled away. The remaining legless figures looked like bathers wading into deep water. The colonnade entrance, once as wide as a town square, had been shrunk by the addition of iron bars and a cage door that was never unguarded.

Inside the Colosseum, a cheering crowd watched two half-naked men fight like dogs.

The battling hods shoved each other about the red clay ring. Their iron collars clanged together as they grappled and strained. In the surrounding bleachers, where students had once sat absorbing the day’s lecture, men now shook their betting slips and shouted themselves crimson.

A lavish balcony haloed the common bleachers. Its railing, sparsely attended a moment before, now grew crowded with noblemen attracted by the uproar. They peered down at the brawl, sipping leaf-green liqueur from crystal glasses and smoking black cigarillos that stank like wet bedclothes. Magpies and doves swooped about the great dome overhead, driven from their nests by the mounting noise.

Trembling from the effort, the old hod lifted the youth over his head and held him on his shoulders like the yoke of an ox. He turned in a slow circle, showing every seat his defeated rival, who had not ten minutes before strutted out of the tunnel, thumping his chest. The mob bayed. The old hod drove the youth to the ground, where he bounced once and settled in a prostrate sprawl.

Every spectator in the arena—save one—made thunder with his hands. The victorious hod paraded with his arms up, his expression as inscrutable as an executioner’s hood.

A team of groomers emerged from the tunnels that ran under the stands. Some raked the clay; others dragged the moaning youth underground. The victor was gathered last, his iron collar hooked to a pair of poles, by which he was escorted from the floor amid a shower of losing betting slips.

In the arena’s lower tier, the man who refused to clap scanned the balcony railing, studying the faces of the noblemen in military and dining jackets. They did not pay him the compliment of acknowledgment.

As a wanted man, Thomas Senlin found the snub amusing. But the same realities that had frustrated his own search for Marya now befuddled the ringdom’s search for him. The Tower overwrote the obsessions and longings of men and women with an indifference so intense it almost seemed purposeful. One did not have to hide long nor change much to disappear inside the churning mass. Thomas Senlin had slipped again into the camouflage of the crowd. It didn’t hurt his anonymity that the published bounty for the pirate Tom Mudd included a sketch of a much fiercer-looking man, with an anvil chin, cannonball cheeks, and a gaze like a crucible full of slag. Perhaps Commissioner Pound had been too embarrassed to describe the man who’d robbed and eluded him honestly as a thin man with kindly eyes and a nose like a rudder.

The crowd funneled from the bleachers to the lobby, a great vaulted room that didn’t so much echo as boom with voices and commotion. A rowdy queue formed at the concessionary, where cloudy beer was being poured and splashed upon the floor. Another line grew about the betting cages, where guards in severe black-and-gold uniforms watched the room for men who were overly drunk or overly distraught. Finding any such show of excess, the guards offered a first warning by rifle butt and a second warning by bayonet.

Caught for the moment in the human vortex, Senlin engaged in some idle eavesdropping. Most of what he heard just concerned the last fight or the next, but one conversation distinguished itself from the rest.

“I heard they’re recalling Commissioner Pound,” a man in a plum-colored vest said.

“It wasn’t in the Reverie this morning,” his companion complained.

“It will be tomorrow, I’d wager. Commissioner Pound: outwitted by a pirate named Mudd!”

“How quick the wind turns!”

Senlin resisted the urge to pull up his collar.

Wedging through, he splashed across a growing lagoon of beer and made his way to the balcony entrance.

A pair of sharp-eyed guards stood at the base of the balcony stairs. They shared a common uniform, which included a gold sash, a saber, a pistol, and, apparently, a mustache. Senlin tried not to look at the swords that hung on their hips as he smiled and said, “Hello!”

One of the guards shifted his forward gaze just long enough to size Senlin up. And seeing nothing deserving further conversation, he looked away.

Senlin reached into his coat pocket, a movement that inspired both men to show him several inches of their swords. With the slow care of a surgeon navigating a wound, Senlin drew out his billfold. He extracted a stiff white card and a five-mina banknote, an amount that once upon a time would’ve been enough to feed his crew for six months. “Perhaps you could give my calling card to the club manager.” The nearest guard, whose mustache had been waxed into two perfect loops, took the money and card. “With my warmest regards,” Senlin said with a wink.

The guard ripped the card and the banknote, turned them, and tore again. He dropped the scraps at Senlin’s feet. Even as Senlin looked down at his destroyed offering, the guard gripped one sleeve of his coat and ripped it half from his shoulder. He repeated the treatment on the other sleeve.

Before he could speak, Senlin was brusquely elbowed aside by the arrival of several men in suits that were as black and sleek as hot tar. The guards saluted, and one said, “Good afternoon, Sir Wilhelm.” Ignoring them, the nobleman continued a cheerful conversation with his companions, all of whom seemed oblivious to the man in a torn gray coat.

This was not Senlin’s first glimpse of the handsome duke, but it was the closest he’d come to the man who’d made off with Marya. Senlin pictured himself stealing the guard’s sidearm. Pictured the shot striking the duke, pictured him crying out in surprise, clutching the mortal wound as he fell at Senlin’s feet in a lifeless knot. Doubtlessly, he would be dead a moment after the duke, leaving Marya twice-widowed and half-rescued. And that assumed she wished to be saved. It was a question only she could answer, and he could not ask.

Senlin had the Sphinx to thank for this absurd state of affairs.

Three days prior, the Sphinx had wasted no time introducing Senlin to his role as contracted spy.

Mere hours after the Sphinx had unveiled Edith’s astonishing new command, the State of Art, he led Senlin down the rose-colored canyon of his home, through one of a hundred indistinguishable doors, and into a queer and cramped dressing room.

Sizing charts hung upon the walls. A seamstress’s dummy stood in one corner, wire ribs rusting through cotton skin. Much of the room was dominated by an immense wardrobe. It quivered and rumbled like a boiling pot. Brass tumblers and dials consumed one of the wardrobe’s doors. Byron, the Sphinx’s stag-headed footman, attended these controls, making minute adjustments and muttering to himself. The Sphinx loomed in one corner, his black robes long and tapering. He looked like a leech with a mirror in its mouth.

Senlin hardly glanced at the Sphinx or his curious wardrobe, which seemed part closet and part engine. His sense of wonder had been depleted by his time in the Bottomless Library, where he had been forcibly nursed off the Crumb with the assistance of nightmares, booby traps, and a feline librarian. He hadn’t yet had time to fully absorb the mysterious vault the Sphinx had shown him, the so-called “Bridge,” which the Brick Layer had built to hold an untold something and sealed for reasons also unspoken. And that was to say nothing of the loss of Senlin’s former command, nor his ill-advised visit to Edith’s room and the kiss they’d shared with the sort of starved passion one expects of the young. It all left him feeling out of sorts.

And then Byron told him to strip to his underclothes.

He reluctantly did, and Byron assaulted him—throat, shoulder, waist, and inseam—with a tailor’s tape he pulled from his pocket. Every new measurement sent Byron back to the wardrobe to turn one tumbler or another.

Senlin was so distracted by the process that he was slow to absorb the Sphinx’s announcement that he would not be traveling with his old crewmates aboard the State of Art and would instead go on ahead to Pelphia, early and alone.

Senlin’s voice rose with his alarm: “But why? We’re all going to the same place, aren’t we? What possible reason could you have for dividing us?”

“Will you stop fidgeting!” Byron said, cinching his tape about Senlin’s chest.

“You mean breathing? Am I being fitted for a casket?”

“Not yet!” Byron said.

“Stop it, both of you.” The Sphinx’s voice buzzed and crackled over the humming of the wardrobe. “Senlin, please reassure me that you’re not an absolute fool. Tell me, why would it be a mistake for all of you to march, arm in arm, into Pelphia together?”

Ignoring Byron’s probing as best he could, Senlin said, “I suppose it might make us easier to recognize. We are a rather … memorable troop.”

“Ah! It’s good to see the Crumb didn’t cook your brains entirely.”

The stag bleated in frustration. “You’d think your ears were on your hips, the way you twist about!”

Senlin was too distracted to return Byron’s quip. “So I’m to go alone?”

“Don’t be so dramatic, Tom! We’ll exchange messages every day,” the Sphinx said, and when Senlin asked how such a thing would be done, the Sphinx described his mechanical moths, which were predecessors to the clockwork butterflies Senlin had already seen. “The moths are more rudimentary; they record sound but not sight. But for the purpose of correspondence, they’re more than sufficient. Byron will intercept your missives from the State of Art, pass on any pertinent information to the crew, then send them on to me. You’ll only be alone in body. In spirit, we’ll be as close as moth and flame.”

“Splendid,” Senlin murmured.

“Now, I know you will be tempted to look for your wife, especially once the inevitable lonesomeness sets in. But listen to me: You will make no effort to contact your wife when you—”

“If!” Senlin gripped the carpet with his bare toes. “If she is there.” He had been poisoned by hope once already and was determined not to let it happen again.

“Byron, do you have the paper I gave you?” the Sphinx asked.

The stag threw the tape measure over his shoulder with a snort and began to rummage through his leather satchel. After a moment, he produced a folded newspaper and handed it to Senlin before retreating to the panel of the wheezing wardrobe.

Senlin read the headline aloud in a dwindling voice: “‘Duke Wilhelm Horace Pell to Wed the Mermaid, Marya of Isaugh.’” He looked to the date at the top. The paper was almost seven months old. He wished to read on, but his arms failed him, taken by a sudden weakness. The paper fell like a stage curtain.

It was a fact now, and yet his mind was slow to accept it. The feeling reminded him of that nauseating confusion he had felt when, as a boy, he had been told that his grandfather had died in the night. He believed it was true at once because his mother had told him, and she would never lie about such a thing. But that evening, when he was shown his grandfather’s body, washed, and dressed, and laid out for the wake, it had become true in a different way. Believing was not the same as knowing.

“She married the count,” he murmured, his throat closing about the words.

“Duke, actually,” the Sphinx said.

A cry like a swooping bird interrupted them, the sound rising from a murmur into a muffled shriek. It seemed to come from the wardrobe, which rattled more and more frantically, its hinges chattering like teeth.

Neither the Sphinx nor Byron seemed overly concerned. When the shaking abruptly stopped, Byron pulled the latch on the wardrobe and opened the doors.

Inside, Voleta Boreas hung from a wooden coat hanger as if it were a trapeze. Pink-cheeked and with scarves and stockings tangled about her neck, she leapt into the dressing room. Despite her relatively small stature, Voleta had a way of filling up every room she walked into. With her dark hair cut short, her wide mouth and bright violet eyes seemed to have grown more prominent. “That was absolutely terrifying!” she joyfully exclaimed. “It goes so blasted fast! I’ve never ridden anything so fast in my life! It was like falling in double time. I have to go again!”

“I told you, Voleta, it’s not a ride. It’s the Fardrobe,” Byron said. “And you’re supposed to be waiting your turn to be fitted, not running amok in my storehouse.”

Voleta, apparently oblivious to Senlin’s state of half dress, began speaking to him in an exhilarated rush: “It goes to a vault full of gowns and suits and socks, all hanging like bats from the ceiling. There’s hardly any light, and there are these mechanical arms that reach out and snatch the hangers, and then whiz all around through the walls!” As she spoke, she passed the loose garments she’d collected along the way to an unhappy Byron. “I promise you, Captain, one go-around and that frown will be blown right off your face.” Voleta reached into the back of her blouse and pulled a black velvet disc from the collar. She flipped it about, rapped it with a knuckle, and the disc popped open. Voleta put the top hat on. It sank over her ears at once.

Still in a fog, Senlin handed her the newspaper and said, “I found her.”

Voleta took the paper, her expression blooming with excitement and then wilting as she read. Sheepish now, she pulled the hat from her head. “A duke? She married a duke? I don’t understand. She’s your wife. She can’t … I thought she … I’m so sorry, Captain.”

“Not captain anymore,” the Sphinx said, as if searching for a bottom to Senlin’s humiliation.

Senlin turned back to the Sphinx and said, “Did she want to marry him or was she coerced?”

“Eavesdroppers and newspapers can only tell so much, I’m afraid. I don’t know whether Marya said, ‘I do,’ or if the duke said, ‘You will.’ What was whispered, what lies in the heart—those are things that require a closer ear.” The Sphinx shrank as he spoke, his black robes pooling upon the floor. He put his face, large as a silver platter, level with Senlin’s.

“Then I must ask her,” Senlin said, resolute in his undershirt.

“Is your memory really so short? I just told you, you are not to speak to your wife. You won’t write her letters. You won’t spy on her from the bushes. You won’t go near her, her husband, or their home.”

What had begun as cold, numb sorrow now warmed Senlin from core to extremity. “How can you be so heartless? Is there no humanity in you at all? You act as if she’s a fancy, an errand. She is not! She is a woman whose life I ruined! Ruined with my pride, my inability, my selfishness. I will find her. I will offer my help if she needs it, my heart if she wants it, my head, even if she would see it on a stake! And you, with your plots and contracts, you with your cowardly mask and tick-tock heart, you will not stop me!”

Voleta and Byron stood frozen in the silence that followed. They waited to see whether Tom would survive his outburst, or if the Sphinx would spark the life from him.

At last, the Sphinx sighed, the sound like coins rattling down a drain. Reaching up, the Sphinx twisted the mirror. It fell away even as the black shroud piled upon the floor. Senlin gasped. Her face was a quilt of metal and flesh that was as tan and creased as a walnut. Plates of precious alloys crowded about an eyepiece that would’ve been better suited to a microscope than the face of an ancient woman. Perhaps strangest of all, she did not stand, but sat cross-legged upon a floating platter. Senlin passed a hand near the red glow that emanated from the bottom of the floating platform. The air there was vaguely warm and unsettled, as if possessed by static, but it did not burn him.

He looked to Voleta to share his amazement. When she caught him looking, she blurted out a not particularly convincing “Oh my god! It’s a flying crone!”

“Really, Voleta,” the Sphinx said, moving the brass horn that distorted her speech away from her mouth. Her unfiltered voice was creaking and reedy but remarkably ordinary. “The only living persons who have seen my face are standing in this room. You see, Thomas, a business contract is just a sort of artificial trust. But we four are beyond that now.”

“But I don’t … Why me?” he asked. “And why Voleta?”

The Sphinx pulled thoughtfully at the thick lobe of one ear. “Perhaps because you are capable of remorse. There is nothing in the world so inspiring of trust as regret. And I trust Voleta because she reminds me so much of myself—”

“We’re virtually twins,” Voleta piped up.

“—right down to that pert mouth of hers.”

“But if you have such faith in me,” Senlin said, his confusion verging upon ire, “if you understand me so well, why would you forbid me to speak to Marya? Surely, you must know remorse is not enough. If amends can be made, they must be.”

“Just because I trust you, Thomas, doesn’t mean you’re not sometimes a fool.” Before Senlin could balk, the unveiled Sphinx pressed on, her tray pacing the carpet before him. “Let’s think this through; let’s think how your attempt to see your wife would probably go. Let’s say that you defy my counsel, my orders, your contract, and our friendship, and go in search of Marya. Let’s say you actually manage to meet her, which is no small feat because she is married to a popular and very powerful duke. How do you think she will react when her husband of old materializes?” The Sphinx stopped shifting about, as if to give Senlin a chance to reply, though as soon as he drew a breath, she carried on for him. “Perhaps she’ll be happy! Perhaps she’ll say, ‘Oh, Tom! My love has returned! I am saved! Carry me home!’” The Sphinx clapped her still-gloved hands together in a mockery of joy. “But perhaps she’ll be angry. Perhaps she’ll say, ‘You! You ruined my life, you miserable worm!’” The Sphinx shook a fist at him.

“Whichever it is, whatever her feelings are, one thing is certain: She will be surprised to see you. And what do people do when they are actually surprised?” The Sphinx cut her gaze toward Voleta. “What if she blurts out your name or gasps or faints or screams? It won’t really matter whether it’s done out of delight or fright if the duke overhears it. Do you really think he will be pleased to see you, his rival? If you are lucky, he will take his displeasure out on you. But if he is an unreasonable or jealous man, if he is cruel, might he not take that displeasure out on her as well?”

Senlin scowled at the Sphinx’s logic because he could not think of how to argue against it. At least, not yet. “What do you propose?”

“Voleta will speak to Marya on your behalf.” The Sphinx swept an arm toward the young woman. “Voleta can wear a dress. She can curtsy her way into court. She can, I think, get invited to the sort of parties the duke and duchess go to. She can wait for the right moment, and when it arrives, she can make a discreet inquiry.”

“I don’t want Voleta doing my dirty—” Senlin began, but Voleta interrupted him.

“I’ll do it.”

“Wait a minute. You don’t know what you’re volunteering for. Is it dangerous?” Senlin asked.

“Of course it’s dangerous!” The Sphinx laughed. “Most things worth doing are. But she won’t be alone. I’m sending the amazon with her.”

Senlin had no doubt that Iren would protect Voleta with her life, but she was still only one person. What could she do if the duke or the navy or the whole ringdom turned against them? “I can’t put their necks on the block for my mistakes. We’ll have to think of something—”

“You aren’t captain anymore,” Voleta said. She did not say it meanly, yet even so, the words stung. “You can’t give orders any longer, Mr. Tom. So. I want to go to Pelphia.”

“The parties are glorious!” Byron said, with a happy shake of his antlers. He helped Senlin slide his arms into a new white-collared shirt. “The people are dreadful, but the parties are sublime. I’ve read a hundred stories: the waltzes, the music, the hors d’oeuvres, the wits—”

“I’m not going for any of that!” Voleta said. “I don’t care about waltzes and minces and how-do-you-dos! I’m going because this man saved my life. He saved my brother’s life. So it’s my turn to be … good, or whatever it is we are.” She turned to Senlin. “I promise, I’ll bring her home.”

“That’s incredibly brave and selfless and … thank you.” Senlin knew her too well to think she would be dissuaded once she had decided on a course. “But, Voleta, please, you must be honest with her. Tell her everything. Tell her about the thievery, the piracy, and the bloodshed. Tell her about the starving, and the Crumb addiction, and … all of it.”

“All of it?” Voleta said, squeezing the hat flat again. “What am I supposed to say, ‘Hullo! You don’t know me, but your old husband sent me to tell you what an awful person he is now. A real stinker! But he wants you back. Oh, yes, he does! Wait, madam, where are you going?’” She popped the hat out with her fist. “That’s a hard sale, Mr. Tom.”

Senlin pushed his arms into the jacket Byron held out for him. It fit perfectly. It felt strange to wear a new, tailored suit again. He looked at his scarred and weathered hands, protruding from the pristine cuffs. He felt like two different people stitched together.

“Marya has to know what she’s signing up for.” He tried to put his hands in his pockets but found them sewn shut. “I won’t trick her. I won’t pretend I am the man she married. I don’t think I’m completely ruined, or at least not beyond redemption, and perhaps there will be a homecoming for us, but if she is happy in her new life, I would not pluck her from it.”

Not knowing what to say to this sincere declaration, Voleta attempted a curtsy. She bent both knees, threw her head downward, and popped up again like a spring.

Byron brayed in horror and said, “What on earth was that? Are you bobbing for apples?”

“There’ll be enough time for practicing curtsies later,” the Sphinx intervened before Voleta could retort. “Now that your business has been settled for the moment, I’d like to discuss mine.”

“I imagine it has something to do with Luc Marat,” Senlin said.

“I suspect it does. Someone is destroying my spies, my butterflies. Specifically, someone inside the Colosseum. That’s where the locals watch hods bleed for their amusement.”

“They sound like lovely people,” Voleta said.

“It’s just the sort of injustice that rallies hods to Marat’s cause. It’s not that Marat is truly against bloodshed; he just prefers it to be spilled on his own account. Whether he’s involved or not, one thing seems certain: Someone doesn’t want me to know what’s going on inside the Colosseum.”

“But if it isn’t Marat, if it’s the locals who’re blinding you, what do they have to hide?”

“Ah! Now you’re asking the right questions. I knew you’d make a fine spy, Tom. There is one other thing you should probably know. The Colosseum is run by the Coterie, which you may recall Duke Wilhelm is a member of. So your investigation will probably put you right in his way. But you will do your best to avoid him.”

“For such a large place, the Tower seems awfully small sometimes,” Senlin said with a sour smile.

“‘Small,’ he says. Small.” The wand she gripped began to spit and spark like green wood on a fire. “If you’d prefer I can dispatch you to the ringdom of Thane, where a hundred rifles have vanished from a locked armory. Or I can ship you to the ringdom of Japhet, where a street recently collapsed, apparently the result of some errant tunneling. Or I could send you to Banner-Wick, where two libraries have burned down in the past month. The shipyards in Morick have suffered from repeated sabotage. Perhaps I should send you there!” Her voice had risen to a shout. “I choose to dispatch you to Pelphia because we share a common interest there. But do not confuse my charity with fate. Only a small man believes the Tower is small.”

Feeling sufficiently chastised, Senlin raised his hands in surrender. “I’m sorry. It was a facile thing to say.”

The apology seemed to appease the Sphinx. The bright spark dwindled from the tip of her wand. She pulled what appeared to be a little ball bearing from the sleeve of one glove. She presented the copper pellet to Senlin, who was horrified to see it sprout eight legs and run a circle about her open palm. The Sphinx tut-tutted and tapped the mechanical arachnid with her finger. The spider balled up again. “Swallow this.”

“You can’t be serious,” Senlin said.

The Sphinx pointed at Voleta, whose mouth was already open. “Young lady, if you say one word, you’ll be eating this instead. Now look, Thomas, it’s perfectly harmless. It will only help us find you if you get lost. Consider it a safety line, like the airmen wear.” The Sphinx again presented him with the balled-up spider. “Or if you’d rather, I can have Ferdinand assist you with the insertion?”

Senlin took the pill, placed it on his tongue, and swallowed with a small shudder.

“There we are. That wasn’t so bad, was it?” She plucked a leather billfold from her tray and handed it to him. Opening it, Senlin fo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...