- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

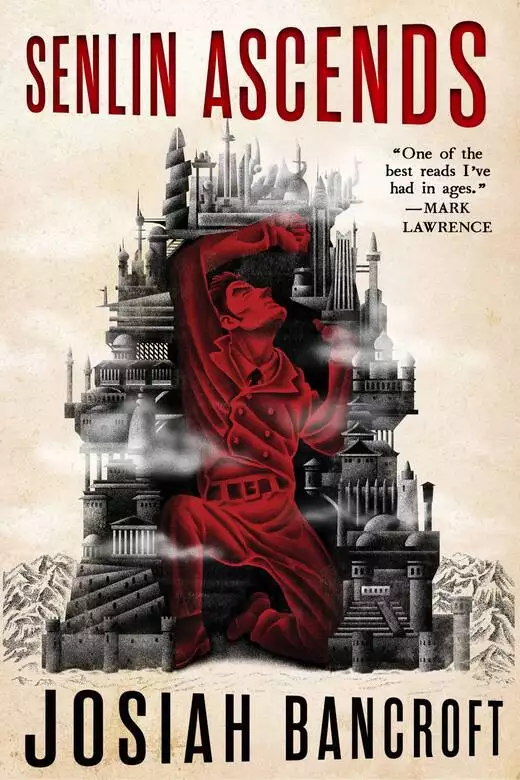

The first book in the stunning and strange debut fantasy series that's receiving major praise from some of fantasy's biggest authors such as Mark Lawrence and Django Wexler.

The Tower of Babel is the greatest marvel in the world. Immense as a mountain, the ancient Tower holds unnumbered ringdoms, warring and peaceful, stacked one on the other like the layers of a cake. It is a world of geniuses and tyrants, of airships and steam engines, of unusual animals and mysterious machines.

Soon after arriving for his honeymoon at the Tower, the mild-mannered headmaster of a small village school, Thomas Senlin, gets separated from his wife, Marya, in the overwhelming swarm of tourists, residents, and miscreants.

Senlin is determined to find Marya, but to do so he'll have to navigate madhouses, ballrooms, and burlesque theaters. He must survive betrayal, assassins, and the long guns of a flying fortress. But if he hopes to find his wife, he will have to do more than just endure.

This quiet man of letters must become a man of action.

The Books of Babel

Senlin Ascends

Arm of the Sphinx

Release date: August 22, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Senlin Ascends

Josiah Bancroft

The Royal Palace, Rasailles

“Throw!” came the command from the green.

A bushel of fresh-cut blossoms sailed into the air, chased by darts and the tittering laughter of lookers-on throughout the gardens.

It took quick work with her charcoals to capture the flowing lines as they moved, all feathers and flares. Ostentatious dress was the fashion this spring; her drab grays and browns would have stood out as quite peculiar had the young nobles taken notice of her as she worked.

Just as well they didn’t. Her leyline connection to a source of Faith beneath the palace chapel saw to that.

Sarine smirked, imagining the commotion were she to sever her bindings, to appear plain as day sitting in the middle of the green. Rasailles was a short journey southwest of New Sarresant but may as well have been half a world apart. A public park, but no mistaking for whom among the public the green was intended. The guardsmen ringing the receiving ground made clear the requirement for a certain pedigree, or at least a certain display of wealth, and she fell far short of either.

She gave her leyline tethers a quick mental check, pleased to find them holding strong. No sense being careless. It was a risk coming here, but Zi seemed to relish these trips, and sketches of the nobles were among the easiest to sell. Zi had only just materialized in front of her, stretching like a cat. He made a show of it, arching his back, blue and purple iridescent scales glittering as he twisted in the sun.

She paused midway through reaching into her pack for a fresh sheet of paper, offering him a slow clap. Zi snorted and cozied up to her feet.

It’s cold. Zi’s voice sounded in her head. I’ll take all the sunlight I can get.

“Yes, but still, quite a show,” she said in a hushed voice, satisfied none of the nobles were close enough to hear.

What game is it today?

“The new one. With the flowers and darts. Difficult to follow, but I believe Lord Revellion is winning.”

Mmm.

A warm glow radiated through her mind. Zi was pleased. And so for that matter were the young ladies watching Lord Revellion saunter up to take his turn at the line. She returned to a cross-legged pose, beginning a quick sketch of the nobles’ repartee, aiming to capture Lord Revellion’s simple confidence as he charmed the ladies on the green. He was the picture of an eligible Sarresant noble: crisp-fitting blue cavalry uniform, free-flowing coal-black hair, and neatly chiseled features, enough to remind her that life was not fair. Not that a child raised on the streets of the Maw needed reminding on that point.

He called to a group of young men nearby, the ones holding the flowers. They gathered their baskets, preparing to heave, and Revellion turned, flourishing the darts he held in each hand, earning himself titters and giggles from the fops on the green. She worked to capture the moment, her charcoal pen tracing the lines of his coat as he stepped forward, ready to throw. Quick strokes for his hair, pushed back by the breeze. One simple line to suggest the concentrated poise in his face.

The crowd gasped and cheered as the flowers were tossed. Lord Revellion sprang like a cat, snapping his darts one by one in quick succession. Thunk. Thunk. Thunk. Thunk. More cheering. Even at this distance it was clear he had hit more than he missed, a rare enough feat for this game.

You like this one, the voice in her head sounded. Zi uncoiled, his scales flashing a burnished gold before returning to blue and purple. He cocked his head up toward her with an inquisitive look. You could help him win, you know.

“Hush. He does fine without my help.”

She darted glances back and forth between her sketch paper and the green, trying to include as much detail as she could. The patterns of the blankets spread for the ladies as they reclined on the grass, the carefree way they laughed. Their practiced movements as they sampled fruits and cheeses, and the bowed heads of servants holding the trays on bended knees. The black charcoal medium wouldn’t capture the vibrant colors of the flowers, but she could do their forms justice, soft petals scattering to the wind as they were tossed into the air.

It was more detail than was required to sell her sketches. But details made it real, for her as much as her customers. If she hadn’t seen and drawn them from life, she might never have believed such abundance possible: dances in the grass, food and wine at a snap of their fingers, a practiced poise in every movement. She gave a bitter laugh, imagining the absurdity of practicing sipping your wine just so, the better to project the perfect image of a highborn lady.

Zi nibbled her toe, startling her. They live the only lives they know, he thought to her. His scales had taken on a deep green hue.

She frowned. She was never quite sure whether he could actually read her thoughts.

“Maybe,” she said after a moment. “But it wouldn’t kill them to share some of those grapes and cheeses once in a while.”

She gave the sketch a last look. A decent likeness; it might fetch a half mark, perhaps, from the right buyer. She reached into her pack for a jar of sediment, applying the yellow flakes with care to avoid smudging her work. When it was done she set the paper on the grass, reclining on her hands to watch another round of darts. The next thrower fared poorly, landing only a single thunk. Groans from some of the onlookers, but just as many whoops and cheers. It appeared Revellion had won. The young lord pranced forward to take a deep bow, earning polite applause from across the green as servants dashed out to collect the darts and flowers for another round.

She retrieved the sketch, sliding it into her pack and withdrawing a fresh sheet. This time she’d sketch the ladies, perhaps, a show of the latest fashions for—

She froze.

Across the green a trio of men made way toward her, drawing curious eyes from the nobles as they crossed the gardens. The three of them stood out among the nobles’ finery as sure as she would have done: two men in the blue and gold leather of the palace guard, one in simple brown robes. A priest.

Not all among the priesthood could touch the leylines, but she wouldn’t have wagered a copper against this one having the talent, even if she wasn’t close enough to see the scars on the backs of his hands to confirm it. Binder’s marks, the by-product of the test administered to every child the crown could get its hands on. If this priest had the gift, he could follow her tethers whether he could see her or no.

She scrambled to return the fresh page and stow her charcoals, slinging the pack on her shoulder and springing to her feet.

Time to go? Zi asked in her thoughts.

She didn’t bother to answer. Zi would keep up. At the edge of the green, the guardsmen patrolling the outer gardens turned to watch the priest and his fellows closing in. Damn. Her Faith would hold long enough to get her over the wall, but there wouldn’t be any stores to draw on once she left the green. She’d been hoping for another hour at least, time for half a dozen more sketches and another round of games. Instead there was a damned priest on watch. She’d be lucky to escape with no more than a chase through the woods, and thank the Gods they didn’t seem to have hounds or horses in tow to investigate her errant binding.

Better to move quickly, no?

She slowed mid-stride. “Zi, you know I hate—”

Shh.

Zi appeared a few paces ahead of her, his scales flushed a deep, sour red, the color of bottled wine. Without further warning her heart leapt in her chest, a red haze coloring her vision. Blood seemed to pound in her ears. Her muscles surged with raw energy, carrying her forward with a springing step that left the priest and his guardsmen behind as if they were mired in tar.

Her stomach roiled, but she made for the wall as fast as her feet could carry her. Zi was right, even if his gifts made her want to sick up the bread she’d scrounged for breakfast. The sooner she could get over the wall, the sooner she could drop her Faith tether and stop the priest tracking her binding. Maybe he’d think it no more than a curiosity, an errant cloud of ley-energy mistaken for something more.

She reached the vines and propelled herself up the wall in a smooth motion, vaulting the top and landing with a cat’s poise on the far side. Faith released as soon as she hit the ground, but she kept running until her heartbeat calmed, and the red haze faded from her sight.

The sounds and smells of the city reached her before the trees cleared enough to see it. A minor miracle for there to be trees at all; the northern and southern reaches had been cut to grassland, from the trade roads to the Great Barrier between the colonies and the wildlands beyond. But the Duc-Governor had ordered a wood maintained around the palace at Rasailles, and so the axes looked elsewhere for their fodder. It made for peaceful walks, when she wasn’t waiting for priests and guards to swoop down looking for signs she’d been trespassing on the green.

She’d spent the better part of the way back in relative safety. Zi’s gifts were strong, and thank the Gods they didn’t seem to register on the leylines. The priest gave up the chase with time enough for her to ponder the morning’s games: the decadence, a hidden world of wealth and beauty, all of it a stark contrast to the sullen eyes and sunken faces of the cityfolk. Her uncle would tell her it was part of the Gods’ plan, all the usual Trithetic dogma. A hard story to swallow, watching the nobles eating, laughing, and playing at their games when half the city couldn’t be certain where they’d find tomorrow’s meals. This was supposed to be a land of promise, a land of freedom and purpose—a New World. Remembering the opulence of Rasailles palace, it looked a lot like the old one to her. Not that she’d ever been across the sea, or anywhere in the colonies but here in New Sarresant. Still.

There was a certain allure to it, though.

It kept her coming back, and kept her patrons buying sketches whenever she set up shop in the markets. The fashions, the finery, the dream of something otherworldly almost close enough to touch. And Lord Revellion. She had to admit he was handsome, even far away. He seemed so confident, so prepared for the life he lived. What would he think of her? One thing to use her gifts and skulk her way onto the green, but that was a pale shadow of a real invitation. And that was where she fell short. Her gifts set her apart, but underneath it all she was still her. Not for the first time she wondered if that was enough. Could it be? Could it be enough to end up somewhere like Rasailles, with someone like Lord Revellion?

Zi pecked at her neck as he settled onto her shoulder, giving her a start. She smiled when she recovered, flicking his head.

We approach.

“Yes. Though I’m not sure I should take you to the market after you shushed me back there.”

Don’t sulk. It was for your protection.

“Oh, of course,” she said. “Still, Uncle could doubtless use my help in the chapel, and it is almost midday …”

Zi raised his head sharply, his eyes flaring like a pair of hot pokers, scales flushed to match.

“Okay, okay, the market it is.”

Zi cocked his head as if to confirm she was serious, then nestled down for a nap as she walked. She kept a brisk pace, taking care to avoid prying eyes that might be wondering what a lone girl was doing coming in from the woods. Soon she was back among the crowds of Southgate district, making her way toward the markets at the center of the city. Zi flushed a deep blue as she walked past the bustle of city life, weaving through the press.

Back on the cobblestone streets of New Sarresant, the lush greens and floral brightness of the royal gardens seemed like another world, foreign and strange. This was home: the sullen grays, worn wooden and brick buildings, the downcast eyes of the cityfolk as they went about the day’s business. Here a gilded coach drew eyes and whispers, and not always from a place as benign as envy. She knew better than to court the attention of that sort—the hot-eyed men who glared at the nobles’ backs, so long as no city watch could see.

She held her pack close, shoving past a pair of rough-looking pedestrians who’d stopped in the middle of the crowd. They gave her a dark look, and Zi raised himself up on her shoulders, giving them a snort. She rolled her eyes, as much for his bravado as theirs. Sometimes it was a good thing she was the only one who could see Zi.

As she approached the city center, she had to shove her way past another pocket of lookers-on, then another. Finally the press became too heavy and she came to a halt just outside the central square. A low rumble of whispers rolled through the crowds ahead, enough for her to know what was going on.

An execution.

She retreated a few paces, listening to the exchanges in the crowd. Not just one execution—three. Deserters from the army, which made them traitors, given the crown had declared war on the Gandsmen two seasons past. A glorious affair, meant to check a tyrant’s expansion, or so they’d proclaimed in the colonial papers. All it meant in her quarters of the city was food carts diverted southward, when the Gods knew there was little enough to spare.

Voices buzzed behind her as she ducked down an alley, with a glance up and down the street to ensure she was alone. Zi swelled up, his scales pulsing as his head darted about, eyes wide and hungering.

“What do you think?” she whispered to him. “Want to have a look?”

Yes. The thought dripped with anticipation.

Well, that settled that. But this time it was her choice to empower herself, and she’d do it without Zi making her heart beat in her throat.

She took a deep breath, sliding her eyes shut.

In the darkness behind her eyelids, lines of power emanated from the ground in all directions, a grid of interconnecting strands of light. Colors and shapes surrounded the lines, fed by energy from the shops, the houses, the people of the city. Overwhelmingly she saw the green pods of Life, abundant wherever people lived and worked. But at the edge of her vision she saw the red motes of Body, a relic of a bar fight or something of that sort. And, in the center of the city square, a shallow pool of Faith. Nothing like an execution to bring out belief and hope in the Gods and the unknown.

She opened herself to the leylines, binding strands of light between her body and the sources of the energy she needed.

Her eyes snapped open as Body energy surged through her. Her muscles became more responsive, her pack light as a feather. At the same time, she twisted a Faith tether around herself, fading from view.

By reflex she checked her stores. Plenty of Faith. Not much Body. She’d have to be quick. She took a step back, then bounded forward, leaping onto the side of the building. She twisted away as she kicked off the wall, spiraling out toward the roof’s overhang. Grabbing hold of the edge, she vaulted herself up onto the top of the tavern in one smooth motion.

Very nice, Zi thought to her. She bowed her head in a flourish, ignoring his sarcasm.

Now, can we go?

Urgency flooded her mind. Best not to keep Zi waiting when he got like this. She let Body dissipate but maintained her shroud of Faith as she walked along the roof of the tavern. Reaching the edge, she lowered herself to have a seat atop a window’s overhang as she looked down into the square. With luck she’d avoid catching the attention of any more priests or other binders in the area, and that meant she’d have the best seat in the house for these grisly proceedings.

She set her pack down beside her and pulled out her sketching materials. Might as well make a few silvers for her time.

The Tower of Babel is most famous for the silk fineries and marvelous airships it produces, but visitors will discover other intangible exports. Whimsy, adventure, and romance are the Tower’s real trade.

—Everyman’s Guide to the Tower of Babel, I. V

It was a four-day journey by train from the coast to the desert where the Tower of Babel rose like a tusk from the jaw of the earth. First, they had crossed pastureland, spotted with fattening cattle and charmless hamlets, and then their train had climbed through a range of snow-veined mountains where condors roosted in nests large as haystacks. Already, they were farther from home than they had ever been. They descended through shale foothills, which he said reminded him of a field of shattered blackboards, through cypress trees, which she said looked like open parasols, and finally they came upon the arid basin. The ground was the color of rusted chains, and the dust of it clung to everything. The desert was far from deserted. Their train shared a direction with a host of caravans, each a slithering line of wheels, hooves, and feet. Over the course of the morning, the bands of traffic thickened until they converged into a great mass so dense that their train was forced to slow to a crawl. Their cabin seemed to wade through the boisterous tide of stagecoaches and ox-drawn wagons, through the tourists, pilgrims, migrants, and merchants from every state in the vast nation of Ur.

Thomas Senlin and Marya, his new bride, peered at the human menagerie through the open window of their sunny sleeper car. Her china-white hand lay weightlessly atop his long fingers. A little troop of red-breasted soldiers slouched by on palominos, parting a family in checkered headscarves on camelback. The trumpet of elephants sounded over the clack of the train, and here and there in the hot winds high above them, airships lazed, drifting inexorably toward the Tower of Babel. The balloons that held the ships aloft were as colorful as maypoles.

Since turning toward the Tower, they had been unable to see the grand spire from their cabin window. But this did not discourage Senlin’s description of it. “There is a lot of debate over how many levels there are. Some scholars say there are fifty-two, others say as many as sixty. It’s impossible to judge from the ground,” Senlin said, continuing the litany of facts he’d brought to his young wife’s attention over the course of their journey. “A number of men, mostly aeronauts and mystics, say that they have seen the top of it. Of course, none of them have any evidence to back up their boasts. Some of those explorers even claim that the Tower is still being raised, if you can believe that.” These trivial facts comforted him, as all facts did. Thomas Senlin was a reserved and naturally timid man who took confidence in schedules and regimens and written accounts.

Marya nodded dutifully but was obviously distracted by the parade of humanity outside. Her wide, green eyes darted excitedly from one exotic diversion to the next: What Senlin merely observed, she absorbed. Senlin knew that, unlike him, Marya found spectacles and crowds exhilarating, though she saw little of either back home. The pageant outside her window was nothing like Isaugh, a salt-scoured fishing village, now many hundreds of miles behind them. Isaugh was the only real home she’d known, apart from the young women’s musical conservatory she’d attended for four years. Isaugh had two pubs, a Whist Club, and a city hall that doubled as a ballroom when occasion called for it. But it was hardly a metropolis.

Marya jumped in her seat when a camel’s head swung unexpectedly near. Senlin tried to calm her by example but couldn’t stop himself from yelping when the camel snorted, spraying them with warm spit. Frustrated by this lapse in decorum, Senlin cleared his throat and shooed the camel out with his handkerchief.

The tea set that had come with their breakfast rattled now, spoons shivering in their empty cups, as the engineer applied the brakes and the train all but stopped. Thomas Senlin had saved and planned for this journey his entire career. He wanted to see the wonders he’d read so much about, and though it would be a trial for his nerves, he hoped his poise and intellect would carry the day. Climbing the Tower of Babel, even if only a little way, was his greatest ambition, and he was quite excited. Not that anyone would know it to look at him: He affected a cool detachment as a rule, concealing the inner flights of his emotions. It was how he conducted himself in the classroom. He didn’t know how else to behave anymore.

Outside, an airship passed low enough to the ground that its tethering lines began to snap against heads in the crowd. Senlin wondered why it had dropped so low, or if it had only recently launched. Marya let out a laughing cry and covered her mouth with her hand. He gaped as the ship’s captain gestured wildly at the crew to fire the furnace and pull in the tethers, which was quickly done amid a general panic, but not before a young man from the crowd had caught hold of one of the loose cords. The adventuresome lad was quickly lifted above the throng, his feet just clearing the box of a carriage before he was swung up and out of view.

The scene seemed almost comical from the ground, but Senlin’s stomach churned when he thought of how the youth must feel flying on the strength of his grip high over the sprawling mob. Indeed, the entire brief scene had been so bizarre that he decided to simply put it out of his mind. The Guide had called the Market a raucous place. It seemed, perhaps, an understatement.

He’d never expected to make the journey as a honeymooner. More to the point, he never imagined he’d find a woman who’d have him. Marya was his junior by a dozen years, but being in his midthirties himself, Senlin did not think their recent marriage very remarkable. It had raised a few eyebrows in Isaugh, though. Perched on rock bluffs by the Niro Ocean, the townsfolk of Isaugh were suspicious of anything that fell outside the regular rhythms of tides and fishing seasons. But as the headmaster, and the only teacher, of Isaugh’s school, Senlin was generally indifferent to gossip. He’d certainly heard enough of it. To his thinking, gossip was the theater of the uneducated, and he hadn’t gotten married to enliven anyone’s breakfast-table conversation.

He’d married for entirely practical reasons.

Marya was a good match. She was good tempered and well read; thoughtful, though not brooding; and mannered without being aloof. She tolerated his long hours of study and his general quiet, which others often mistook for stoicism. He imagined she had married him because he was kind, even tempered, and securely employed. He made fifteen shekels a week, for an annual salary of thirteen minas; it wasn’t a fortune by any means, but it was sufficient for a comfortable life. She certainly hadn’t married him for his looks. While his features were separately handsome enough, taken altogether they seemed a little stretched and misplaced. His nickname among his pupils was “the Sturgeon” because he was thin and long and bony.

Of course, Marya had a few unusual habits of her own. She read books while she walked to town—and had many torn skirts and skinned knees to show for it. She was fearless of heights and would sometimes get on the roof just to watch the sails of inbound ships rise over the horizon. She played the piano beautifully but also brutally. She’d sing like a mad mermaid while banging out ballads and reels, leaving detuned pianos in her wake. And even still, her oddness inspired admiration in most. The townsfolk thought she was charming, and her playing was often requested at the local public houses. Not even the bitter gray of Isaugh’s winters could temper her vivacity. Everyone was a little baffled by her marriage to the Sturgeon.

Today, Marya wore her traveling clothes: a knee-length khaki skirt and plain white blouse with a somewhat eccentric pith helmet covering her rolling auburn hair. She had dyed the helmet red, which Senlin didn’t particularly like, but she’d sold him on the fashion by saying it would make her easier to spot in a crowd. Senlin wore a gray suit of thin corduroy, which he felt was too casual, even for traveling, but which she had said was fashionable and a little frolicsome, and wasn’t that the whole point of a honeymoon, after all?

A dexterous child in a rough goatskin vest climbed along the side of the train with rings of bread hooped on one arm. Senlin bought a ring from the boy, and he and Marya sat sharing the warm, yeasty crust as the train crept toward Babel Central Station, where so many tracks ended.

Their honeymoon had been delayed by the natural course of the school year. He could’ve opted for a more convenient and frugal destination, a seaside hotel or country cottage in which they might’ve secluded themselves for a weekend, but the Tower of Babel was so much more than a vacation spot. A whole world stood balanced on a bedrock foundation. As a young man, he’d read about the Tower’s cultural contributions to theater and art, its advances in the sciences, and its profound technologies. Even electricity, still an unheard-of commodity in all but the largest cities of Ur, was rumored to flow freely in the Tower’s higher levels. It was the lighthouse of civilization. The old saying went, “The earth doesn’t shake the Tower; the Tower shakes the earth.”

The train came to a final stop, though they saw no station outside their window. The conductor came by and told them that they’d have to disembark; the tracks were too clogged for the train to continue. No one seemed to think it unusual. After days of sitting and swaying on the rails, the prospect of a walk appealed to them both. Senlin gathered their two pieces of luggage: a stitched leather satchel for his effects, and for hers, a modest steamer trunk with large casters on one end and a push handle on the other. He insisted on managing them both.

Before they left their car and while she tugged at the tops of her brown leather boots and smoothed her skirt, Senlin recited the three vital pieces of advice he’d gleaned from his copy of Everyman’s Guide to the Tower of Babel. Firstly, keep your money close. (Before they’d departed, he’d had their local tailor sew secret pockets inside the waists of his pants and the hem of her skirt.) Secondly, don’t give in to beggars. (It only emboldens them.) And finally, keep your companions always in view. Senlin asked Marya to recite these points as they bustled down the gold-carpeted hall connecting train cars. She obliged, though with some humor.

“Rule four: Don’t kiss the camels.”

“That is not rule four.”

“Tell that to the camels!” she said, her gait bouncing.

And still neither of them was prepared for the scene that met them as they descended the train’s steps. The crowd was like a jelly that congealed all around them. At first they could hardly move. A bald man with an enormous hemp sack humped on his shoulder and an iron collar about his neck knocked Senlin into a red-eyed woman; she repulsed him with an alcoholic laugh and then shrank back into the swamp of bodies. A cage of agitated canaries was passed over their heads, shedding foul-smelling feathers on their shoulders. The hips of a dozen black-robed women, pilgrims of some esoteric faith, rolled against them like enormous ball bearings. Unwashed children loaded with trays of scented tissue flowers, toy pinwheels, and candied fruit wriggled about them, each child leashed to another by a length of rope. Other than the path of the train tracks, there were no clear roads, no cobblestones, no curbs, only the rust-red hardpan of the earth beneath them.

It was all so overwhelming, and for a moment Senlin stiffened like a corpse. The bark of vendors, the snap of tarps, the jangle of harnesses, and the dither of ten thousand alien voices set a baseline of noise that could only be yelled over. Marya took hold of her husband’s belt just at his spine, startling him from his daze and goading him onward. He knew they couldn’t very well just stand there. He gathered a breath and took the first step.

They were drawn into a labyrinth of merchant tents, vendor carts, and rickety tables. The alleys between stands were as tangled as a child’s scribble. Temporary bamboo rafters protruded everywhere over them, bowing under jute rugs, strings of onions, punched tin lanterns, and braided leather belts. Brightly striped shade sails blotted out much of the sky, though even in the shade, the sun’s presence was never in doubt. The dry air was as hot as fresh ashes.

Senlin plodded on, hoping to find a road or signpost. Neither appeared. He allowed the throng to offer a path rather than forge one himself. When a gap opened, he leapt into it. After progressing perhaps a hundred paces in this manner, he had no idea which direction the tracks lay. He regretted wandering away from the tracks. They could’ve followed them to the Babel Central Station. It was unsettling how quickly he’d become disoriented.

Still, he was careful to occasionally turn and construct a smile for Marya. The beam of her smile never wavered. There was no reason to worry her with the minor setback.

Ahead, a bare-chested boy fanned the hanging carcasses of lambs and rabbits to keep a cloud of flies from settling. The flies and sweet stench wafting from the butcher’s stall drove the crowd back, creating a little space for them to pause a moment, though the stench was nauseating. Placing Marya’s trunk between them, Senlin dried his neck with his handkerchief.

“It certainly is busy,” Senlin said, trying not to seem as flustered as he felt, though Marya hardly noticed; she was

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...