When I was sixteen I made a pact with the devil. He came in the form of a fawning, red-faced and rather plump middle-aged man by the name of Mr Foot; but I was too innocent, too inexperienced in the ways of men, to guess his unsavoury intentions. Oh, I had an inkling, certainly. A twinge of intuition, a sense that his offer came with a price. But I was too excited to care. I ignored the undertones, so obvious in retrospect.

It was a pact born of my need for validation; my need, I suppose, for love: for isn’t love the foundation of all other needs? But I only realised this in hindsight. At the time I craved applause, and that’s what Mr Foot offered. Naive as I was, I had little clue as to what this agreement would eventually involve, but Mr Foot wasn’t to know that; in his eyes I was easy pickings. He made the offer, opened a door and blindly I leapt through it. That door was my escape route: from a prison without walls or bars or boundaries, a prison consisting of infinite skies and endless green fields. But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let me explain.

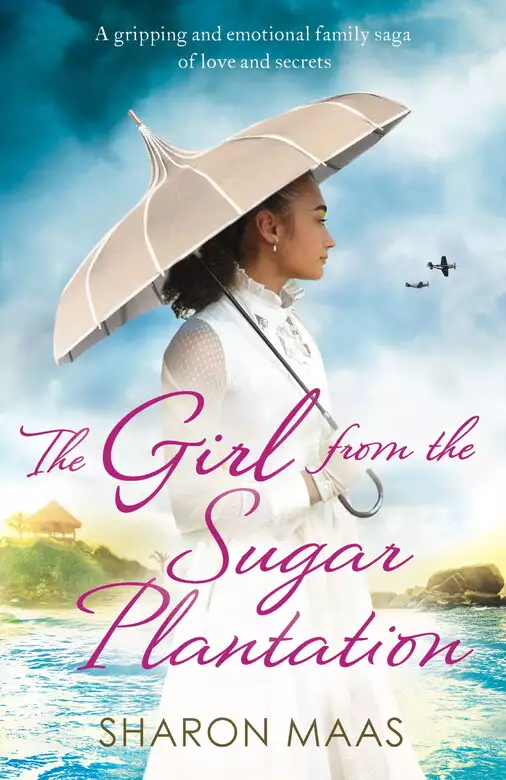

I was born with a sugar spoon in my mouth, heiress to one of the great sugar dynasties of British Guiana, a remote colony perched on South America’s eastern shoulder, tucked neatly between Brazil, Venezuela and two other Guianas. A land of great rivers and far-stretching seas, its arms wrapped around you as a mother. We called it BeeGee, a diminutive so much warmer and intimate than the stern formal title, a name spoken like a luscious secret among those of us who knew and loved her.

BeeGee. I miss it so much. The very word conjures up memories of sunshine and flowers, butterflies and birdsong, beautiful white wooden houses on stilts against a backdrop of succulent green. I tend to forget the ugly parts. I tend to forget that it wasn’t like that for us all; that unhappy as I was, still I was born to privilege, that within the dark underbelly of our little dynasty lay great suffering. I tend to forget that my little private prison was child’s play compared to that of so many of my brothers and sisters; that in fact I was one of the lucky ones, despite my perceived misfortune.

Nevertheless, I was miserable. Our particular dynasty was in danger of falling apart, with only me – female and half-blood, the worst combination possible – as the final twitching limb and potential saviour. The stalwart Englishmen who had wrestled our sugar-gold from the earth (or rather, ensured it was wrestled; lowlier beings did the actual work) were all long gone, leaving behind just the two of us: Mama and me.

Promised Land, our crumbling kingdom, was a ten-thousand-acre estate in the county of Berbice on BeeGee’s Corentyne coast, east of the capital city of Georgetown. It was the only home I’ve ever known, the foundation stone of my identity. From my bedroom window on the upper storey of the estate mansion – rebuilt by Mama after the Great Fire of 1921 – I looked out over a veritable ocean of cane, green as far as the eye could see, reaching out to the horizon, to the Atlantic in the distance, green ocean merging into brown ocean. All my life I had absorbed the sights, the sounds, the smells of the sugar year. The flood fallowing, when the ratoons, the baby canes, have been planted, when water from the irrigation canals is let into the fields; the planting, the manuring, the weeding: coolie women in once-bright, now faded saris bent low in the muddy fields. The burning of the cane when the air would be filled with the aroma of scalded cane-juice, rich, evocative, unforgettable. The cane growing higher, higher, above my head, even when I sat on horseback – ten feet tall and more.

Then the harvest; swarms of coolies in the fields with their cutlasses, hacking down the giant cane-stalks; blackened by ash and burnt cane-juice, they would carry their bundles of cane on their backs and load the punts waiting on the navigation canals, swearing and shouting as they worked. Then the punts, pulled by mules, slowly making their way along the gridwork of canals to the factory, perched on the edge of the estate, as far away from the house as possible, a groaning monster devouring those canes, sucking them into its bowels, chewing them and grinding them with huge black metallic teeth and belching great black billows of smoke up through its tall chimneys.

A sugar plantation has a spirit of its own, and Promised Land was part of my identity. I had absorbed that spirit and knew it as intimately as I knew the rooms and hallways of our mansion and the paths through the splendid garden Mama had planted around the house, a riot of colour and birdsong.

And yet…

I might be a princess, but I was a deeply flawed one, a princess unworthy of the throne. Not in Mama’s eyes, but in the eyes of the outside world, and they never missed a chance to let me know how imperfect I was. Not blatantly, you understand; but with subtle half-glances, frowns, awkward silences when I appeared, they placed an invisible glass wall between them and me to let me know my place. I never needed it spelled out in so many words; I had eyes. The hierarchy was plain to see, the layers that dictated and defined your place in society, ordained, it seemed by God. Black the bottom, white the top and a multitude of shades in between, with me floating precariously somewhere in the middle. Half-blood. Mixed-breed. Brown. The collective noun was ‘coloured’. A status of its own, containing within itself a wealth of unstated derogatory adjectives.

While adults managed to conceal their contempt beneath a thin veneer of civility, children were not so subtle, nor so polite; children speak out the truth as learned from their parents and called me those names to my face: mongrel, mule, monkey and worse.

Up here in the Corentyne, far away from the incestuous and intricately layered social hierarchy that is Georgetown society, Mama had etched out a status for me. I was her daughter, adopted or not, and that spoke volumes. Mama, as the only female plantation owner in the colony, as a member of the board of the Sugar Producers’ Association, was highly respected. She had a sharp tongue and feared no man. Indeed, men feared her. Everyone did. Mama always got her way; that’s what they all said. Many hated her, even; but she was inviolable. I, on the other hand, was an open target: a child, a girl, a lightning rod. A pariah.

My status as princess pertained only within the narrow confines of our own plantation; beyond the plantation, beyond the Corentyne, I was nothing.

And so I fled. I fled from the sense of wretchedness and nothingness, from the sense that I did not belong, the knowledge that not all the plantations in the colony could rectify the error of my blood. I fled into the arms of music.

For more than all of this, more than the Atlantic reaching to the horizon, the endless fields of green, that vast Corentyne sky, as wide as it was high, everywhere space and more space, more than the air I breathed and the sun on my back and the birds and the flowers, it was music that gave wings to my soul. It was the piano I loved. My fingers longed to dance along the keys of a piano, fashioning such wings, wings of music, wings to let me soar. Most of all, music brought healing to that deep wound invisible to all but myself.

And that’s where Mr Foot came in. Mr Foot held out a hand of opportunity, and I grasped it as a drowning man grasps at a floating branch.

It all began at the traditional Christmas ball at Promised Land. The usual crowd, the Bees and the Crawfords and the Wrights and the Feet (as everyone called Mr and Mrs Foot), from the neighbouring estates of Albion and Dieu Merci, Port Mourant, Rose Hall and Waterloo, Sophia’s Lot and Monkey Jump, had gathered at our house. After dinner came the entertainment, and I played the piano accompaniment to the usual Christmas carols: ‘Joy to the World’, ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem’, ‘Silent Night’ and the rest, and even a little solo at the end. The applause was enthusiastic and, for once, I earned words of praise from those thin-lipped, pale-faced denizens of the plantocracy.

I dare say much of the tribute I earned was to flatter Mama, whom, her being a member of the board of the Sugar Producers’ Association, everyone wanted to sweeten. Yet, I hoped behind the applause also lay genuine appreciation. Because I was good. I knew I was good, and I say this without vanity.

I first learned to play at the age of five, when Oma Ruth was still living with Aunt Winnie in Georgetown. Mama and I had been in town, staying at the Park Hotel – Mama had some business with the Sugar Producers’ Association that would keep her there for a month, and she left me with Aunt Winnie and Oma Ruth during the day. That’s when Oma taught me to play.

‘She’s a natural,’ Oma had said, and that was the beginning of it all. ‘She must have piano lessons when you go home!’ Oma insisted, and though Mama wasn’t keen on the idea – Mama always joked she didn’t have a single musical bone in her body – I begged and cajoled and, in the end, she arranged for me to visit a teacher once a week in New Amsterdam. I’d always been able to wrap Mama around my little finger, and the next thing I begged for was a piano of my own. From the day the piano was delivered I was a child obsessed. I practised for hours on end, before school in the morning, after school in the afternoon. When I was fourteen my piano teacher said, ‘I can’t teach her any more. She’s better than me.’ And that was the end of that.

It was frustrating, as I knew there was still room for improvement, but BeeGee was a barren desert when it came to musical education; Georgetown was bad enough, but out here in the country? There was no one to teach me, and all I could do was play and play and play. ‘You’re worse than your grandmother,’ Mama would complain, and I took that as a compliment.

That Christmas concert was the start of it all; the first time I’d played in public, the first time Mr Foot, the administrative manager of Albion plantation, heard me play. Afterwards he drew me aside for a private word. Even that was an extraordinary occurrence; white people, adults, never spoke to me beyond the cursory obligatory murmurings of polite society: How do you do? Merry Christmas! What a pretty dress! I was flattered from the start.

‘Miss Smedley-Cox,’ said Mr Foot, ‘What a magnificent performance! Such a talented young lady – as talented as you are beautiful. You know, while you were playing I had an idea. I wonder if…’

He hesitated. And then, with much hemming and hawing, he continued:

‘I was wondering if you would like to play at the reception at the Georgetown Club in a month’s time? It’s being held as a welcome party for the young lad who is coming to be trained in estate management – the heir to the Campbell throne, if you will. It will be quite a big do – everyone will be there – and I’ve been scratching my head trying to pull together the entertainment. It’s going to be a splendid evening, and to have you play for us, as enthrallingly as you did just now – why, I’m sure we’d all be delighted.’

‘You – you want me to play? At the Georgetown Club?’

I could not believe my ears. I had never set foot in the Georgetown Club, the Buckingham Palace of the colony. Everyone knew it was barred to coloureds. Mama, of course, was a regular there; due to her position on the Sugar Producers’ Association, she often had to attend this function or that, and somehow to date she had managed to circumvent my exclusion with a modicum of dignity. Even she was not willing to break such a time-honoured taboo, not even to pamper my pride.

But to play there? To actually play at the exclusive Georgetown Club? To play for a real English audience beyond the paltry groups of neighbours and estate staff? To play in public, to be heard and, hopefully, appreciated and applauded by the planter aristocracy, the Booker snobs, the white upper class? I couldn’t believe it. I gaped and stuttered, and Mr Foot coughed and continued.

‘I’ll have to ask the SPA’s permission, of course; but seeing as your mother is on the board, and knowing of her persuasiveness – she brings such a feminine touch to all our meetings! – I have no doubt that it will be approved. After all, you aren’t coming as a guest, exactly—’

At the word ‘guest’ he turned lobster-red and hesitated, and I understood. As part of the entertainment I would be an employee at the function, not an invitee, and so convention could be sustained. My status there would be clear, as clear as that of the coloured maids who would be serving the sandwiches and the black barman who would be mixing the cocktails and pouring the rum punch. The only difference was that I would not be in a starched maid’s uniform.

I understood, and he understood that I understood. I was to know my place. I was not an invitee; I was not to mingle, talk to the guests, behave in any way that would compromise myself – or him. I was to come, play and go.

‘You will be paid accordingly, of course,’ he added. ‘Quite deservedly. Of course, there are other musicians – there’s a rather good calypso fellow coming, Doctor Jangles, and we have a steel band lined up as well. Just to give it all a local touch. You know, the exotic element.’

He paused at this point.

‘You do understand, don’t you, that this is as a special favour from me? You do understand that it’s a great’ – he coughed ‘ – privilege for you to be invited. An unusual – ah – kindness. There are several other more experienced pianists in Georgetown, after all. And that I hope – er – would be delighted – well. No need to be indelicate. We do have an understanding, don’t we, my dear?’ And he looked at me, and winked. It was that wink I chose to ignore.

Though young, I was not a complete newcomer to the ways of men. I had already endured my portion of advances and intentions, advances that would certainly have been scandalous had I been of higher status; that is, white like them, like Mama. On more than one occasion I had been pinched; once, a young man had swept me behind a curtain and tried to kiss me. I had shoved him away. Men perfected the art of placing hands on knees beneath the dining table, or playing with feet, or, when they danced with me, of letting fingers wander where they shouldn’t. That wink should have been easy to interpret, and at some unseen level I did understand. But I was not listening at that level, I was listening only to the fever of unrealised ambition. Ignoring the wink, I nodded vigorously and I’m sure my eyes must have radiated all kinds of acquiescence, as did my eager smile.

Encouraged, Mr Foot continued:

‘As I was saying we do have the usual local entertainers but it would be rather wonderful to have some European music as well. I’m sure young Mr Campbell would appreciate it. And you, Miss Cox – well, you really are – for your age – the best such musician the colony has to offer. A very gifted young lady, and so beautiful as well, your golden skin, that magnificent mane of yours…’

He actually reached out, now, to touch my hair. Our housemaid Katie had done it for me and had managed to tame it so much that it cascaded over my shoulders and down my back in a tumble of curls and ringlets while my crown remained demure, kept obediently in place by a complicated arrangement of plaits and pleats and velvet ribbons. My hair was the bane of my existence. It refused to be restrained in any way. It kinked and curled and flew away when I would prefer it to fall neatly into place. It tangled and teased, refusing to bend to my will. If it were not for Katie I don’t know what I would have done – cut it all off, most probably, and run around like a darkie boy with a close-cropped cap. That would certainly have suited me. But I did have Katie, and she did have magical hands where hair was concerned.

I drew back from Mr Foot’s eagerly grasping hand, but not from him. I was interested; of course I was! I knew just one thing: this was my big chance. My debut. Yes, I would play for them; I would stun them with the beauty of music. Because my hands too were magical, on the keys of a piano.

‘Mr Foot,’ I said, ‘I should be delighted to play at the Georgetown Club!’

With those words I sealed our little pact.

‘What about your mother?’ he asked, rather nervously. ‘You’ll need her cooperation. Her permission.’

‘Don’t worry about Mama,’ I said, with more confidence than I felt. ‘I’ll persuade her.’

Mama, as I’d feared, was not in favour. ‘As an employee?’ she exclaimed when I told her the following day. ‘How can you play as an employee? You are my daughter! It’s an insult, I hope you haven’t agreed?’

‘Oh Mama! Of course, I agreed! Don’t you see? This is my chance!’

‘Darling, I’m sorry, but you can’t agree to this sort of thing without my consent. You’re still a child.’

‘I’m not, Mama, I’m not! I’m sixteen, almost adult! And I’m the best pianist in the country, Mr Foot himself said so. And I really want to; I really, really want to. Please let me? Please, please, please!’

I danced around her with clasped hands and pleading eyes; this was the best way to melt any objections she might raise. I knew this from past arguments. Mama might have a heart of steel to others, but not to me. I knew how to melt her. But this time she narrowed her eyes and glared at me.

‘Mary Grace! Have you no pride? No shame? Can’t you feel the insult?’

‘No! It’s not an insult, it’s an honour! It really is, Mama! Everyone will be there, Mr Foot said; even the Governor himself! It’s my chance, Mama, my first chance and maybe my last! Please let me… It means so much to me!’

Her eyes softened at that. She took my hands in hers and squeezed them, then let go and placed them over my ears and gave my head a jiggle as if trying to shake sense into me. Then she let go and took my hand and led me into the gallery. ‘Darling, we need to talk,’ she said. She picked up the cushion on one of the cane chairs, shook it out to free it of lizards or insects, puffed it up, replaced it and gestured for me to sit. My heart sank. Another lecture was coming on, and all I wanted was a simple yes. This ‘we need to talk’ was always a signal for an embarrassing and awkward mother-to-daughter conversation. I didn’t want to hear it.

‘Mama…’ I began. ‘Please, just—’

‘No. You need to hear this,’ she said firmly, and I knew then that there was no avoiding it.

‘Look at me,’ she said then, and I looked up and met her eyes. Mine were moist; I could feel it. I hated these little talks. They were like fingernails scratching at a soreness, and instead of alleviating it, only made it worse. It was a soreness that would not go away, however much I tried; a soreness that tore away every sense of value I could muster on my own, every notion of my own self-worth.

Even the belief that I was the country’s best pianist – according to Mr Foot – could not heal that soreness.

‘Darling, this is a cruel world we live in.’ It was a hollow statement, and so I nodded. It meant nothing. I kept my eyes lowered, now: I did not want to meet hers.

‘And we all have our burdens to bear. British Guiana is a world that belongs to the British. We have to accept that. They set the standards. They lay the rules.’

I looked up then. ‘Why do you say they?’ I cried. ‘You are one of them! Look at you, white as any of them!’

She chuckled then, and glanced at her bare forearm. ‘Well – apart from the sun’s attempts to turn me brown as a berry, that’s true!’

‘So if you’re British and I’m – I’m your daughter, that makes me British too!’

I met her gaze square on, challenging her to deny it.

The smile vanished from her lips. ‘It’s not as easy as that,’ she said. ‘It’s not easy at all. Darling, you know the problem. You know the difference! You’ve been dealing with it all your life, but now it’s time to grow up and face some ugly truths.’

That’s what she thought. Just because a child hides away the wound, has learned to smile and laugh it all away, doesn’t mean she’s dealt with it. It just means she can act well. I’d never told Mama about the taunts and the jibes I’d parried all my life. As a young child, I’d attended the plantation’s senior staff primary school, where all the children were British, and white, except me. I’d never told her about the name-calling. I’d never told her the reason why I never entered the senior staff compound to play tennis with my peers, or use the pool. I’d never told her of the mothers, and the teachers; they might not call me names, but I had learned to gauge an adult’s response to me by the look in their eyes and the tone of their voice as much as through their actual words. Some relief had come when I moved to New Amsterdam High School, for the pupils there were mixed, and I found friends who looked like me. But the hurt had lodged itself into my consciousness and there it had stuck: not visible to anyone, least of all to Mama, and only felt by me when someone scratched at it. As she was doing now.

Now, Mama said: ‘Darling, Georgetown is no place for you. The Georgetown Club – you can’t go there. You can’t play there. I never told you – but – well—’

She stopped. ‘Don’t make this difficult for me!’ she cried then. ‘You must know. You must feel it? Those people, they’ll be hateful to you. They’ll be rude. They’ll – they’ll tell you things – lies – insult you – me. The very fact that Mr Foot has invited you as an employee, an entertainer, should tell you all you need to know. You could never go there as a guest. It’s whites only. You need to know that. You’d be little more than a servant. And yet you’re my daughter. My daughter! They won’t accept my daughter!’

The more words she uttered, the more loaded those words became. Loaded with anger, and loathing, and spite. And the more I understood.

‘This isn’t about me at all, is it, Mama?’ I said then. ‘It’s about you. The insult to you. When they reject me, they reject you.’

I sprang to my feet. Tears stung my eyes. Mama, I knew, would never relent. Mama was proud, and vain, and adamant. She would rather see me miss this chance than accept the insult inherent in the invitation. I made to rush away, but as I passed she grabbed my wrist and pulled me back.

‘Wait – no. Mary Grace, don’t go. We still need to talk. It’s not about the Georgetown Club, it’s about – something else.’

I glared at her. ‘About what?’

She lowered her eyes. ‘About – us. You and me. You asked… you wanted to know – I said I’d tell you one day…’

‘Oh.’ I stopped, and looked down at her, and then retraced my steps, and sat myself down.

‘You always wanted to know…’ she began. And, all of a sudden, I knew what was coming. This was to be the day of truth. Finally.

Mama, usually so confident, so forceful, so dominant in all matters, had an Achilles heel. I had discovered it years ago, when I first started asking why.

Why, when both my parents were white – I had seen photos of my father – was I only a few shades lighter than the labourers who worked our fields and our factory? Obviously, I was adopted. But who were my birth parents? What happened to them? Were they still alive? Did they abandon me? Did they ever love me? Why had Mama and Papa taken me in? Had they chosen me or were they somehow forced to take me? Did Mama love me in spite of my skin colour? I knew she didn’t like dark-skinned people. She cursed them every day. Was I the exception? Did she really love me, or was she just pretending? As much as she’d have loved a white child of her own?

I wanted, I needed, to hear it from her. I wanted to hear her say she had chosen me and loved me and it didn’t matter about my skin colour or my blood or my birth: that she loved me all the same. That I was her real daughter, even if only adopted.

I must have been seven or eight when I first asked. Mama had hedged and hawed. ‘It’s a little bit hard for you to understand, darling,’ she’d said. ‘I’ll tell you later.’

But I had not dropped the questions. I pestered Mama with these questions, and always she pushed me away, referred me to a time when I was older and she would tell all. ‘You’re too young to understand,’ she’d say.

But I needed to know. I badgered and bothered her until one day – I must have been about ten – flustered beyond anything I’d ever seen, she cried out: ‘All right, if you must know! If you must know, I’ll tell you but you won’t like it. Do you still want to know?’

So I nodded. ‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Very well then. Your mother was a servant on one of the plantations. A black woman. Your father was – a white man from Georgetown. I don’t know him. Your birth mother – she died – she died of – in childbirth. Are you happy now?’

I looked at her, straight in the eye. She looked away. That’s when I knew there was more to the story, a lot more; but that’s all I would be getting that day.

So all I said was: ‘Thank you for telling me.’ And I ran away to my secret place in the garden and cried my eyes out. But the next day, more questions came. What was my birth mother’s name? Did she have brothers and sisters? Parents? They’d be my relatives, after all. Could I go and visit them? Were they in Georgetown? Perhaps they’d love me, and I’d love them back. And so my questions did not cease; indeed, they became yet more detailed. I was curious, too, about my father. Unsure about the facts of life, I wondered why Mama didn’t know who he was. Had he been married to my mother? Could white men marry black women? Was it possible? She must know! Why didn’t he want me? Where was he?

Mama meant well, but outspoken in all other circumstances, on this topic she became evasive. She told me lies. I could see right through those lies; that he had disappeared, left the country, all kinds of things. I wished she’d stop. Stop dangling the truth before my eyes in thinly veiled obscurities, in mysterious ambiguities that only made me more curious. Mama was no prude; I wished she’d just come out with it. Might as well try to squeeze blood from a stone.

‘These are difficult questions. It’s a long story. You’re a child – you can’t really grasp it all. When you grow up, I’ll tell you everything.’

‘You promise? Cross your heart and hope to die?’

She smiled then, and had taken me on her lap, and whispered it: ‘Cross my heart and hope to die. I’ll tell you the whole story when you grow up.’

But I wanted exact dates. ‘When will I be grown up?’

‘When you’re – twenty-one.’

‘Twenty-one! That’s ages away!’

‘That’s the age when people are adults, though.’

‘I can’t wait that long! Please, Mama – please! Don’t make me wait that long! I need to know!’

I pulled away from her, tried to ease myself off her lap, but she pulled me back.

‘All right then. I’ll tell you when you’re – eighteen.’

‘That’s still too old! Fourteen!’

She laughed a mocking laugh. ‘Fourteen? Why, at fourteen you’re still a child. I said you need to be adult to understand certain things. I won’t tell you a day before you’re… you’re—’

‘Sixteen!’ I cried. ‘If you say sixteen I promise never to ask again, I promise to wait.’

She mulled for a while, thinking it over, and then she said, reluctantly, ‘Very well, then. Sixteen it is.’

‘You promise?’

‘I promise. But you must promise not to ask again.’

I promised.

And now I was sixteen. The day had, it seemed, arrived.

I’d promised never to ask again, but I had not promised not to find out on my own. The more Mama played hide-and-seek, the more I’d been driven to pry.

Because of course Mama’s hint of a long story had only made me all the more curious. I had long been making my own investigations. That’s why, when I finally did turn sixteen, I did not even bother to ask.

And that’s why Mama’s overly dramatic ‘You always wanted to know…’, with its promise of deep secrets to be revealed, now came as an anticlimax.

‘Oh, that!’ I exclaimed. ‘About my birth parents, you mean? I already know, Mama. I found out.’

She visibly paled. ‘You found out? How? Did someone tell you? How…? Darling, if you’ve heard rumours…’

I’d never seen her this flustered, hot and red. She picked up a fan from the glass-topped gallery table and began to fan herself vigorously. I sat back in my wicker chair and laughed and reached out and took her hand.

‘Nobody told me, Mama. I searched and I found. I found out all on my own.’

‘But how? Where?’ She pulled her hand away and started to scratch her temples. Her face had turned red as a lobster, so I laughed again.

‘I’m clever, aren’t I? You should have hidden the documents better.. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved