- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

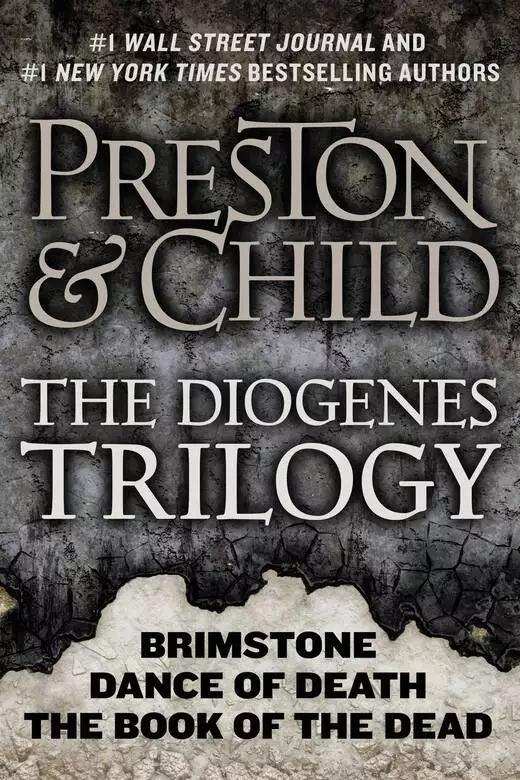

Now, available for the first time together in a single volume: a digital-only, value-priced omnibus edition of the "Diogenes Trilogy": Brimstone, Dance of Death, and The Book of the Dead --featuring Pendergast's mysterious brother--by #1 New York Times bestselling authors Preston & Child. BRIMSTONE: A body is found in the attic of a fabulous Long Island estate. There is a hoofprint scorched into the floor, and the stench of sulfur chokes the air. When FBI Special Agent Pendergast investigates the gruesome crime, he discovers that thirty years ago four men conjured something unspeakable. Has the devil come to claim his due? DANCE OF DEATH: Two brothers. One, top FBI Agent, Aloysius Pendergast. The other, Diogenes, a brilliant and twisted criminal. An undying hatred between them. Now, a perfect crime. And the ultimate challenge: Stop me if you can. BOOK OF THE DEAD: A talented FBI agent, rotting away in a high security prison for a murder he did not commit. His psychotic brother, about to perpetrate a horrific crime. A young woman with an extraordinary past, on the edge of a violent breakdown. An ancient Egyptian tomb about to be unveiled at a celebrity-studded New York gala, an enigmatic curse released. Memento Mori.

Release date: December 1, 2012

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 1437

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Diogenes Trilogy

Douglas Preston

Early-morning sunlight gilded the cobbled drive of the staff entrance at the New York Museum of Natural History, illuminating a glass pillbox just outside the granite archway. Within the pillbox, a figure sat slumped in his chair: an elderly man, familiar to all museum staff. He puffed contentedly on a calabash pipe and basked in the warmth of one of those false-spring days that occur in New York City in February, the kind that coaxes daffodils, crocuses, and fruit trees into premature bloom, only to freeze them dead later in the month.

“Morning, doctor,” Curly said again and again to any and all passersby, whether mailroom clerk or dean of science. Curators might rise and fall, directors might ascend through the ranks, reign in glory, then plummet to ignominious ruin; man might till the field and then lie beneath; but it seemed Curly would never be shifted from his pillbox. He was as much a fixture in the museum as the ultrasaurus that greeted visitors in the museum’s Great Rotunda.

“Here, pops!”

Frowning at this familiarity, Curly roused himself in time to see a messenger shove a package through the window of his pillbox. The package had sufficient momentum to land on the little shelf where the guard kept his tobacco and mittens.

“Excuse me!” Curly said, rousing himself and waving out the window. “Hey!” But the messenger was already speeding away on his fat-tire mountain bike, black rucksack bulging with packages.

“Goodness,” Curly muttered, staring at the package. It was about twelve inches by eight by eight, wrapped in greasy brown paper, and tied up with an excessive amount of old-fashioned twine. It was so beaten-up Curly wondered if the messenger had been run over by a truck on the way over. The address was written in a childish hand: For the rocks and minerals curator, The Museum of Natural History.

Curly broke up the dottle in the bottom of his pipe while gazing thoughtfully at the package. The museum received hundreds of packages every week from children, containing “donations” for the collection. Such donations included everything from squashed bugs and worthless rocks to arrowheads and mummified roadkill. He sighed, then rose painfully from the comfort of his chair and tucked the package under his arm. He put the pipe to one side, slid open the door of his pillbox, and stepped into the sunlight, blinking twice. Then he turned in the direction of the mailroom receiving dock, which was only a few hundred feet across the service drive.

“What have you got there, Mr. Tuttle?” came a voice.

Curly glanced toward the voice. It was Digby Greenlaw, the new assistant director for administration, who was just exiting the tunnel from the staff parking lot.

Curly did not answer immediately. He didn’t like Greenlaw and his condescending Mr. Tuttle. A few weeks earlier, Greenlaw had taken exception to the way Curly checked IDs, complaining that he “wasn’t really looking at them.” Heck, Curly didn’t have to look at them—he knew every employee of the museum on sight.

“Package,” he grunted in reply.

Greenlaw’s voice took on an officious tone. “Packages are supposed to be delivered directly to the mailroom. And you’re not supposed to leave your station.”

Curly kept walking. He had reached an age where he found the best way to deal with unpleasantness was to pretend it didn’t exist.

He could hear the footsteps of the administrator quicken behind him, the voice rising a few notches on the assumption he was hard of hearing. “Mr. Tuttle? I said you should not leave your station unattended.”

Curly stopped, turned. “Thank you for offering, doctor.” He held out the package.

Greenlaw stared it at, squinting. “I didn’t say I would deliver it.”

Curly remained in place, proffering the package.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake.” Greenlaw reached irritably for the package, but his hand faltered midway. “It’s a funny-looking thing. What is it?”

“Dunno, doctor. Came by messenger.”

“It seems to have been mishandled.”

Curly shrugged.

But Greenlaw still didn’t take the package. He leaned toward it, squinting. “It’s torn. There’s a hole . . . Look, there’s something coming out.”

Curly looked down. The corner of the package did indeed have a hole, and a thin stream of brown powder was trickling out.

“What in the world?” Curly said.

Greenlaw took a step back. “It’s leaking some kind of powder.” His voice rode up a notch. “Oh my Lord. What is it?”

Curly stood rooted to the spot.

“Good God, Curly, drop it! It’s anthrax!”

Greenlaw stumbled backward, his face contorted in panic. “It’s a terrorist attack—someone call the police! I’ve been exposed! Oh my God, I’ve been exposed!”

The administrator stumbled and fell backward on the cobblestones, clawing the ground and springing to his feet, and then he was off and running. Almost immediately, two guards came spilling out of the guard station across the way, one intercepting Greenlaw while the other made for Curly.

“What are you doing?” Greenlaw shrieked. “Keep back! Call 911!”

Curly remained where he was, package in hand. This was something so far outside his experience that his mind seemed to have stopped working.

The guards fell back, Greenlaw at their heels. For a moment, the small courtyard was strangely quiet. Then a shrill alarm went off, deafening in the enclosed space. In less than five minutes, the air was filled with the sound of approaching sirens, culminating in an uproar of activity: police cars, flashing lights, crackling radios, and uniformed men rushing this way and that stringing up yellow biohazard tape and erecting a cordon, megaphones shouting at the growing crowds to back off, while at the same time telling Curly to drop the package and step away, drop the package and step away.

But Curly didn’t drop the package and step away. He remained frozen in utter confusion, staring at the thin brown stream that continued to trickle out of the tear in the package, forming a small pile on the cobbles at his feet.

And now two strange-looking men wearing puffy white suits and hoods with plastic visors were approaching, walking slowly, hands outstretched like something Curly had seen in an old science fiction movie. One gently took Curly by the shoulders while the other slipped the package from his fingers and—with infinite care—placed it in a blue plastic box. The first man led him to one side and began carefully vacuuming him up and down with a funny-looking device, and then they began dressing him, too, in one of the strange plastic suits, all the time telling him in low electronic voices that he was going to be all right, that they were taking him to the hospital for a few tests, that everything would be fine. As they placed the hood over his head, Curly began to feel his mind coming back to life, his body able to move again.

“Scuse me, doctor?” he said to one of the men as they led him off toward a van that had backed through the police cordon and was waiting for him, doors open.

“Yes?”

“My pipe.” He nodded toward the pillbox. “Don’t forget to bring my pipe.”

10

The small group descended the dust-laden staircase of the Tomb of Senef, their shoes leaving prints as in a coating of fresh snow.

Wicherly paused, shining his light around. “Ah. This is what the Egyptians called the God’s First Passage along the Sun’s Path.” He turned toward Nora and Menzies. “Are you interested, or will I be making a bore of myself?”

“By all means,” said Menzies. “Let’s have the tour.”

Wicherly’s teeth gleamed in the dim light. “The problem is, much of the meaning of these ancient tombs still eludes us. They’re easy enough to date, though—this seems a fairly typical New Kingdom tomb, I’d say late XVIIIth Dynasty.”

“Right on target,” said Menzies. “Senef was the vizier and regent to Thutmosis IV.”

“Thank you.” Wicherly absorbed the compliment with evident satisfaction. “Most of these New Kingdom tombs had three parts—an outer, middle, and inner tomb, divided into a total of twelve chambers, which together represented the passage of the Sun God through the underworld during the twelve hours of night. The pharaoh was buried at sunset, and his soul accompanied the Sun God on his solar barque as he made the perilous journey through the underworld toward his glorious rebirth at dawn.”

He shone his light ahead, illuminating a dim portal at the far end. “This staircase would have been filled with rubble, ending in a sealed door.”

They continued descending the staircase, at last reaching a massive doorway topped by a lintel carved with a huge Eye of Horus. Wicherly paused, shining his light on the Eye and the hieroglyphics surrounding it.

“Can you read these hieroglyphics?” asked Menzies.

Wicherly grinned. “I make a pretty good show of it. It’s a curse.” He winked slyly at Nora. “To any who cross this threshold, may Ammut swallow his heart.”

There was a short silence.

McCorkle issued a high-pitched chuckle. “That’s all?”

“To the ancient tomb robber,” said Wicherly, “that would be enough—that’s a heck of a curse to an ancient Egyptian.”

“Who is Ammut?” Nora asked.

“The Swallower of the Damned.” Wicherly pointed his flashlight on a dim painting on the far wall, depicting a monster with a crocodilian head, the body of a leopard, and the grotesque hindquarters of a hippo, squatting on the sand, mouth open, about to devour a row of human hearts. “Evil words and deeds made the heart heavy, and after death Anubis weighed your heart on a balance scale against the Feather of Maat. If your heart weighed more than the feather, the baboon-headed god, Thoth, tossed it to the monster Ammut to eat. Ammut journeyed into the sands of the west to defecate, and that’s where you’d end up if you didn’t lead a good life—a shite, baking in the heat of the Western Desert.”

“That’s more than I needed to hear, thank you, Doctor,” said McCorkle.

“Robbing a pharaoh’s tomb must have been a terrifying experience for an ancient Egyptian. The curses put on any who entered the tomb were very real to them. To cancel the power of the dead pharaoh, they didn’t just rob the tomb, they destroyed it, smashing everything. Only by destroying the objects could they disperse their malevolent power.”

“Fodder for the exhibit, Nora,” Menzies murmured.

After the briefest hesitation, McCorkle stepped across the threshold, and the rest followed.

“The God’s Second Passage,” Wicherly said, shining his light around at the inscriptions. “The walls are covered with inscriptions from the Reunupertemhru, the Egyptian Book of the Dead.”

“Ah! How interesting!” Menzies said. “Read us a sample, Adrian.”

In a low voice, Wicherly began to intone:

The Regent Senef, whose word is truth, saith: Praise and thanksgiving be unto thee, Ra, O thou who rollest on like unto gold, thou Illuminer of the Two Lands on the day of thy birth. Thy mother brought thee forth on her hand, and thou didst light up with splendor the circle which is traveled over by the Disk. O Great Light who rollest across Nu, thou dost raise up the generations of men from the deep source of thy waters . . .

“It’s an invocation to Ra, the Sun God, by the deceased, Senef. It’s pretty typical of the Book of the Dead.”

“I’ve heard about the Book of the Dead,” Nora said, “but I don’t know much about it.”

“It was basically a group of magical invocations, spells, and incantations. It helped the dead make the dangerous journey through the underworld to the Field of Reeds—the ancient Egyptian idea of heaven. People waited in fear during that long night after the burial of the pharaoh, because if he buggered up somehow down in the underworld and wasn’t reborn, the sun would never rise again. The dead king had to know the spells, the secret names of the serpents, and all kinds of other arcane knowledge to finish the journey. That’s why it’s all written on the walls of his tomb—the Book of the Dead was a set of crib notes to eternal life.”

Wicherly chuckled, shining his beam over four registers of hieroglyphics painted in red and white. They stepped toward them, raising clouds of deepening gray dust. “There’s the First Gate of the Dead,” he went on. “It shows the pharaoh getting into the solar barque and journeying into the underworld, where he’s greeted by a crowd of the dead . . . Here in Gate Four they’ve encountered the dreaded Desert of Sokor, and the boat magically becomes a serpent to carry them across the burning sands . . . And this! This is very dramatic: at midnight, the soul of the Sun God Ra unites with his corpse, represented by the mummified figure—”

“Pardon my saying so, Doctor,” McCorkle broke in, “but we’ve still got eight rooms to go.”

“Right, of course. So sorry.”

They proceeded to the far end of the chamber. Here, a dark hole revealed a steep staircase plunging into blackness. “This passage would also have been filled with rubble,” Wicherly said. “To hinder robbers.”

“Be careful,” McCorkle muttered as he led the way.

Wicherly turned to Nora and held out a well-manicured hand. “May I?”

“I think I can handle it,” she said, amused at the old-world courtesy. As she watched Wicherly descend with excessive caution, his beautifully polished shoes heavily coated with dust, she decided that he was far more likely to slip and break his neck than she was.

“Be careful!” Wicherly called out to McCorkle. “If this tomb follows the usual plan, up ahead is the well.”

“The well?” McCorkle’s voice floated back.

“A deep pit designed to send unwary tomb robbers to their death. But it was also a way to keep water from flooding the tomb, during those rare periods when the Valley of the Kings flash-flooded.”

“Even if it remains intact, the well will surely be bridged over,” Menzies said. “Recall that this was once an exhibit.”

They moved forward cautiously, their beams finally revealing a rickety wooden bridge spanning a pit at least fifteen feet deep. McCorkle, gesturing for them to remain behind, examined the bridge carefully with his light, then advanced out onto it. A sudden crack! caused Nora to jump. McCorkle grabbed desperately for the railing. But it was merely the sound of settling wood, and the bridge held.

“It’s still safe,” said McCorkle. “Cross one at a time.”

Nora walked gingerly across the narrow bridge. “I can’t believe this was once part of an exhibit. How did they ever install a well like this in the sub-basement of the museum?”

“It must have been cut into the Manhattan bedrock,” Menzies said from behind. “We’ll have to bring this up to code.”

On the far side of the bridge, they passed over another threshold. “Now we’re in the middle tomb,” said Wicherly. “There would have been another sealed door here. What marvelous frescoes! Here’s an image of Senef meeting the gods. And more verses from the Book of the Dead.”

“Any more curses?” Nora asked, glancing at another Eye of Horus painted prominently above the once-sealed door.

Wicherly shone his light toward it. “Hmmm. I’ve never seen an inscription like this before. The place which is sealed. That which lieth down in the closed place is reborn by the Ba-soul which is in it; that which walketh in the closed space is dispossessed of the Ba-soul. By the Eye of Horus I am delivered or damned, O great god Osiris.”

“Sure sounds like another curse to me,” said McCorkle.

“I would guess it’s merely an obscure quotation from the Book of the Dead. The bloody thing runs to two hundred chapters and nobody’s figured all of it out.”

The tomb now opened up onto a stupendous hall, with a vaulted roof and six great stone pillars, all densely covered with hieroglyphics and frescoes. It seemed incredible to Nora that this huge, ornate space had been asleep in the bowels of the museum for more than half a century, forgotten by almost all.

Wicherly turned, playing his light across the extensive paintings. “This is rather extraordinary. The Hall of the Chariots, which the ancients called the Hall of Repelling Enemies. This was where all the war stuff the pharaoh needed in the afterlife would have been stored—his chariot, bows and arrows, horses, swords, knives, war club and staves, helmet, leather armor.”

His beam paused at a frieze depicting beheaded bodies laid out by the hundreds on the ground, their heads lying in rows nearby. The ground was splattered with blood, and the ancient artist had added such realistic details as lolling tongues.

They moved through a long series of passageways until they came to a room that was smaller than the others. A large fresco on one side showed the same scene of weighing the heart depicted earlier, only much larger. The hideous, slavering form of Ammut squatted nearby.

“The Hall of Truth,” Wicherly said. “Even the pharaoh was judged, or in this case, Senef, who was almost as powerful as a pharaoh.”

McCorkle grunted, then disappeared into the next chamber, and the rest followed. It was another spacious room with a vaulted ceiling, painted with a night sky full of stars, the walls dense with hieroglyphics. An enormous granite sarcophagus sat in the middle, empty. The walls on each side were interrupted by four black doors.

“This is an extraordinary tomb,” said Wicherly, shining the light around. “I had no idea. When you called me, Dr. Menzies, I thought it would be something small but charming. This is stupendous. Where in the world did the museum get it?”

“An interesting story,” Menzies replied. “When Napoleon conquered Egypt in 1798, one of his prizes was this tomb, which he had disassembled, block by block, to take back to France. But when Nelson defeated the French in the Battle of the Nile, a Scottish naval captain finagled the tomb for himself and reassembled it at his castle in the Highlands. In the nineteenth century, his last descendant, the 7th Baron of Rattray, finding himself strapped for cash, sold it to one of the museum’s early benefactors, who had it shipped across the Atlantic and installed while they were building the museum.”

“The baron let go of one of England’s national treasures, I should say.”

Menzies smiled. “He received a thousand pounds for it.”

“Worse and worse! May Ammut swallow the greedy baron’s heart for selling the ruddy thing!” Wicherly laughed, casting his flashing blue eyes on Nora, who smiled politely. His attentiveness was becoming obvious, and he seemed not at all discouraged by the wedding band on her finger.

McCorkle began to tap his foot impatiently.

“This is the burial chamber,” Wicherly began, “which the ancients called the House of Gold. Those antechambers would be the Ushabti Room; the Canopic Room, where all the pharaoh’s preserved organs were stored in jars; the Treasury of the End; and the Resting Place of the Gods. Remarkable, isn’t it, Nora? What fun we’ll have!”

Nora didn’t answer immediately. She was thinking about just how massive the tomb was, and how dusty, and how much work lay ahead of them.

Menzies must have been thinking the same thing, because he turned to her with a smile that was half eager, half rueful.

“Well, Nora,” he said. “It should prove an interesting six weeks.”

11

Gerry Fecteau slammed the door to solitary 44 hard, causing a deafening boom throughout the third floor of Herkmoor Correctional Facility 3. He smirked and winked at his companion as they paused outside the door, listening while the sound echoed through the vast cement spaces before dying slowly away.

The prisoner in 44 was a big mystery. All the guards were talking about him. He was important, that much was clear: FBI agents had come to visit him several times and the warden had taken a personal interest. But what most impressed Fecteau was the tight lid on information. For most new prisoners, it didn’t take long for the rumor mill to grind out the accusation, the crime, the gory details. But in this case, nobody even knew the prisoner’s name, let alone his crime. He was referred to simply by a single letter: A.

On top of that, the man was scary. True, he wasn’t physically imposing: tall and slender with skin so pale it looked like he might have been born in solitary. He rarely spoke, and when he did, you had to lean forward to hear him. No, it wasn’t that. It was the eyes. In his twenty-five years in corrections, Fecteau had never before seen eyes that were so utterly cold, like two glittering silvery chips of dry ice, so far below zero they just about smoked.

Christ, it gave Fecteau a chill just thinking about them.

There was no doubt in Fecteau’s mind this prisoner had committed a truly heinous crime. Or series of crimes, a Jeffrey Dahmer type, a cold-blooded serial killer. He looked that scary. That’s why it gave Fecteau such satisfaction when the order came down that the prisoner was to be moved to solitary 44. Nothing more needed to be said. It was where they sent the hard cases, the ones who needed softening up. Not that solitary 44 was any worse than the other cells in Herkmoor 3 Solitary—all the cells were identical: metal cot, toilet with no seat, sink with only cold running water. What made solitary 44 special, so useful in breaking a prisoner, was the presence of the inmate in solitary 45. The drummer.

Fecteau and his partner, Benjy Doyle, stood on either side of the cell door, making no noise, waiting for the drummer to start up again. He’d paused, as he always did for a few minutes when a new prisoner was installed. But the pause never lasted long.

Then, as if on schedule, Fecteau heard a faint soft-shoe shuffle start up again inside solitary 45. This was followed by the popping sound of lips, and then a low tattoo of fingers drumming against the metal rail of the bed. A little more soft-shoe, some snatches of humming . . . and then, the drumming. It started slowly, and quickly accelerated, a rapid roll breaking off into syncopated riffs, punctuated with a pop or a shuffle, a never-ending sonic flood of inexhaustible hyperactivity.

A smile spread across Fecteau’s face and his eyes met those of Doyle.

The drummer was a perfect inmate. He never shouted, screamed, or threw his food. He never swore, threatened the guards, or trashed his cell. He was neat and tidy, keeping his hair groomed and his body washed. But he had two peculiar characteristics that kept him in solitary: he almost never slept, and he spent his waking hours—all his waking hours—drumming. Never loudly, never in-your-face. The drummer was utterly oblivious to the outside world and the many curses and threats directed at him. He did not even seem to be aware that there was an outside world, and he continued on, never varying, never ruffled or disturbed, totally focused. Curiously, the very softness of the drummer’s sounds were the most unendurable aspect of them: Chinese water torture of the ear.

In transferring the prisoner known as A to solitary, Fecteau and Doyle had had orders to deprive the man of all his possessions, including—especially including, the warden had made clear—writing instruments. They had taken everything: books, sketches, photographs, journals, notebooks, pens and inks. The prisoner was left with nothing—and with nothing to do but listen:

Ba-da-ba-da-ditty-ditty-bop-hup-hup-huppa-huppa-be-bop-be-bop-ditty-ditty-ditty-boom! Ditty-boom! Ditty-boom! Ditty-bada-boom-bada-boom-ba-ba-ba-boom! Ba-da-ba-da-pop! Ba-pop! Ba-pop! Ditty-ditty-datty-shuffle-shuffle-ditty-da-da-da-dit! Ditty-shuffle-tap-shuffle-tap-da-da-dadadada-pop! Dit-ditty-dit-ditty-dap! Dit-ditty . . .

Fecteau had heard enough. It was already getting under his skin. He gestured toward the exit with his chin, and he and Doyle headed hurriedly back down the hall, the sounds of the drummer dying away.

“I give him a week,” said Fecteau.

“A week?” Doyle replied with a snort. “The poor bastard won’t last twenty-four hours.”

12

Lieutenant Vincent D’Agosta lay on his belly, in a freezing drizzle, on a barren hill above the Herkmoor Federal Correctional and Holding Facility in Herkmoor, New York. Next to him crouched the dark form of the man named Proctor. The time was midnight. The great prison spread out in a flat valley below them, brilliantly illuminated by the yellow glare of overhead lights, as surreal an industrial confection as a giant oil refinery.

D’Agosta raised a pair of powerful digital binoculars and once again examined the general layout of the facility. It covered at least twenty acres, consisting of three low, enormous concrete building blocks, set in a U shape, surrounded by asphalt yards, lookout towers, fenced service areas, and guardhouses. D’Agosta knew the first building was the Federal Maximum Security Unit, filled with the very worst violent offenders contemporary America could produce—and that, D’Agosta thought grimly, was saying quite a bit. The second, much smaller area bore the official title of Federal Capital Sentence Holding and Transfer Facility. While New York State had no death penalty, there was a federal death penalty, and this is where those few who had been sentenced to death by the federal courts were held.

The third unit also had a name that could only have been invented by a prison bureaucrat: the Federal High-Risk Violent Offender Pretrial Detention Facility. It contained those awaiting trial for a small list of heinous federal crimes: men who had been denied bail and who were considered at especially high risk of escape or flight. This facility held drug kingpins, domestic terrorists, serial killers who had exercised their trade across state boundaries, and those accused of killing federal agents. In the lingo of Herkmoor, this was the Black Hole.

It was this unit that currently housed Special Agent A. X. L. Pendergast.

While some of the storied state prisons, such as Sing Sing and Alcatraz, were famed for never having had an escape, Herkmoor was the only federal facility that could boast a similar record.

D’Agosta’s binoculars continued to roam the facility, taking in even the minute details he had already spent three weeks studying on paper. Slowly, he worked his way from the central buildings to the outbuildings and, finally, to the perimeter.

At first glance, the perimeter of Herkmoor looked unremarkable. Security consisted of the standard triple barrier. The first was a twenty-four-foot chain-link fence, topped by concertina wire, illuminated by the multimillion-candlepower brilliance of xenon stadium lights. A series of twenty-yard spaces spread with gravel led to the second barrier: a forty-foot cinder-block wall topped with spikes and wire. Along this wall, every hundred yards, was a tower kiosk with an armed guard; D’Agosta could see them moving about, wakeful and alert. A hundred-foot gap roamed by Dobermans led to the final perimeter, a chain-link fence identical to the first. From there, a three-hundred-yard expanse of lawn extended to the edge of the woods.

What made Herkmoor unique was what you couldn’t see: a state-of-the-art electronic surveillance and security system, said to be the finest in the country. D’Agosta had seen the specs to this system—he had, in fact, been poring over them for days—but he still barely understood it. He did not see that as a problem: Eli Glinn, his strange and silent partner—holed up in a high-tech surveillance van a mile down the road—understood it, and that’s what counted.

It was more than a security system: it was a state of mind. Although Herkmoor had suffered many escape attempts, some extraordinarily clever, none had succeeded—and every guard at Herkmoor, every employee, was acutely aware of that fact and proud of it. There would be no bureaucratic turpitude or self-satisfaction here, no sleeping guards or malfunctioning security cameras.

That troubled D’Agosta most of all.

He finished his scrutiny and glanced over at Proctor. The chauffeur was lying prone on the ground beside him, taking pictures with a digital Nikon equipped with a miniature tripod, a 2600mm lens, and specially made CCD chips, so sensitive to light they were able to record the arrival of single photons.

D’Agosta ran over the list of questions Glinn wanted answered. Some were obviously important: how many dogs there were, how many guards occupied each tower, how many guards manned the gates. Glinn had also requested a description of the arrival and departure of all vehicles, with as much information as possible on them. He wanted detailed pictures of the clusters of antennas, dishes, and microwave horns on the building roofs. But other requests were not so clear. Glinn wanted to know, for example, if the area between the wall and the outer fence was dirt, grass, or gravel. He had asked for a downstream sample from the brook running past the facility. Strangest of all, he had asked D’Agosta to collect all the trash he could find in a certain stretch of the brook. He had asked them to observe the prison through a full twenty-four-hour period, keeping a log of every activity they could note: prisoner exercise times, the movements of guards, the comings and goings of suppliers, contractors, and delivery people. He wanted to know the times when the lights went on and off. And he wanted it all recorded to the nearest second.

D’Agosta paused to murmur some observations into the digital recorder Glinn had given him. He heard the faint whirring of

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...