- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

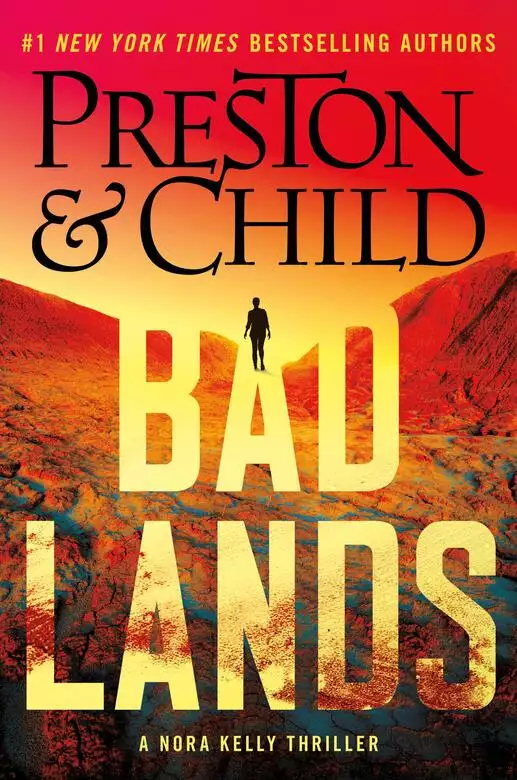

The #1 New York Times bestselling authors Preston & Child return with a thrilling tale in which archaeologist Nora Kelly and FBI Agent Corrie Swanson, while investigating bizarre deaths in the desert, awaken an ancient evil more terrifying than anything they’ve faced before.

In the New Mexico badlands, the skeleton of a woman is found—and the case is assigned to FBI Agent Corrie Swanson. The victim walked into the desert, shedding clothes as she went, and died in agony of heatstroke and thirst. Two rare artifacts are found clutched in her bony hands—lightning stones used by the ancient Chaco people to summon the gods.

Is it suicide or… sacrifice?

Agent Swanson brings in archaeologist Nora Kelly to investigate. When a second body is found—exactly like the other—the two realize the case runs deeper than they imagined. As Corrie and Nora pursue their investigation into remote canyons, haunted ruins, and long-lost rituals, they find themselves confronting a dark power that, disturbed from its long slumber, threatens to exact an unspeakable price.

Release date: June 3, 2025

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Badlands

Douglas Preston

THE WOMAN PAUSED and raised her head, looking over the wavering landscape toward the horizon. She blinked, then blinked again, dazzled by the light. As far as she could see lay a land dotted with hoodoo rock formations: spires and domes of rock, giant boulders balancing on slender stems, trembling and ghostly in the heat. This madness of rock and sand rose into a burning sky dominated by the implacable sun. She could see no traces of life: no trees, no grass, nothing beyond a few stunted prickly pear cacti hugging the sand, shriveled up, dead, more spines than flesh.

The woman lowered her head and continued walking, concentrating on placing one foot in front of the other, always northward, where she knew her destination lay. If only she could get there soon, she would be safe.

She finally understood the expression raging thirst. She thought she had been thirsty before, sometimes very thirsty; but that had been nothing. Nothing. She thought of the Coleridge poem she’d taught so often in English lit it had become a drone in her head. This was what that Ancient Mariner must have felt watching the very boards of his ship shrink under the sun. The thirst that was upon her now was one that seized her mind, refused to let her think of anything else. She could feel her pulse thundering in her temples; the muscles of her legs were shaky and trembling. Her mouth had dried up many miles back, and now her tongue was cracking and swelling. She could taste the iron of blood.

But to stop now would be the worst possible mistake. She had to keep walking.

To get her mind off the thirst, she tried recalling the last few days, but the memories would come back only in pieces: long, dusty bus rides; furtive traveling by night; the air-conditioned Walmart with its racks of cheap clothes; the shabby gas-station restrooms and McDonald’s dumpsters. She recalled burning her money, watching with fascination as the twenty-dollar bills wrinkled in curlicues of flame. The phone had been harder to destroy; in the end, its innards had nevertheless crackled and popped under a burning glaze of lighter fluid.

One foot in front of the other.

A sudden surge of dizziness forced her to brace one hand against a rock. She took a deep breath, let it out slowly. The sun stopped wheeling overhead, returning to a fixed position, a hole of omnipotent heat punched through the fabric of the sky. She spat out the blood weeping from her tongue and continued on.

All she had to do was endure. She tried to say it out loud, endure, but no sound emerged beyond a breathy hiss. It was hot, brutally hot, but nowhere was it so hot as at ground level. She could feel it through the soles of her running shoes. It was a miracle they weren’t actually melting. And, in fact, maybe they were melting: she had once read that in the desert, in full sun, the ground temperature could exceed a hundred and fifty degrees.

Time passed. She walked on. And then came to a tottering stop, feeling a rush of… what?

Of what? She couldn’t articulate what she felt. Everything was so different now. Here in this inferno, it was as if she’d already begun her transformation. The way she felt now was different from just a quarter of an hour before—and light years from the beginning, when she first realized she’d lost sight of a road.

Deliverance. That was the one word that echoed louder than anything else in her mind: louder than the baking heat, louder than even the dreadful thirst. Even now it rose before her. Deliverance.

She could feel the anvil of the sun directly on her head. She counted ten steps forward.

She took off her shirt, peeling it off over her head, and dropped it.

Ten more steps.

She unhooked her bra and shrugged it off. The radiation of the sun now penetrated into her skin.

As she reached for the button of her shorts, she saw movement out of the corner of her eye. She swiftly moved and crouched behind a rock: she’d already seen many things that were merely tricks of her sun-blind vision, but she had to be sure.

This time, it was no phantom or mirage. There was the dot of a person in the distance.

How strange: out in the middle of nowhere, a woman was herding a small flock of sheep. She was maybe a mile away and headed in the opposite direction, and she’d become visible only because she was climbing a low rise with her sheep, taking them over the brow of a ridge.

Had the woman seen her?

She waited, hiding. Nothing. After a while, once she was sure the woman was gone, she eased back up. She unbuttoned her shorts and took them off, dropping them, following with her panties.

The running shoes came off next, and finally the socks. When she placed her bare feet on the hot sand, she felt a sudden, searing pain so excruciating she almost fell to her knees—but she pushed this away as best she could, focusing instead on clenching her last possessions: the objects that, unlike things of this world—money, clothes—she could not, must not, give up.

It was like walking on fire. Her body, not her brain, warned her that this could not last long. But there was no reason to be afraid, no reason at all.

One step. Another.

And then, with unexpected abruptness, her legs gave way and she fell to her knees. Her bare skin hit the ground like meat dropping on a searing griddle. She screamed involuntarily, then fell back, writhing in a useless attempt to escape the heat, every fresh contact with the sand scorching anew, as she felt her skin crack and pop. Fluid sprang out from her skin, but it was like no sweat she’d ever experienced. It made a hissing sound. Through a screen of agony she realized she was cooking. Her body was cooking…

The screams stopped. There was a brief flurry of echoes before silence fell over the landscape once again. Her body went slack against the sand in a dreadful mockery of ease as the first stage of postmortem change—primary relaxation of the musculature—began.

Only her fists remained clenched.

Present day

ALONG THE REMOTE eastern border of the Navajo Nation, dawn broke over the Ah-shi-sle-pah badlands, the sky lightening from midnight blue to pale yellow.

“We’re gonna lose the best light,” the director told Alex Bondi, who was crouched over a small landing pad, preparing a drone camera for a flight. “We’re gonna lose the light!”

Bondi ignored him and continued calibrating the drone’s compass and IMU. He did not point out that the reason they were late was due to the director’s carousing the night before. In order to arrive by the 6 AM sunrise in these remote badlands, they’d had to get up at 2 AM and make a bone-jarring drive over terrible roads. When the director was assisted into his vehicle, he was still drunk. The horrendous drive had shaken the booze out of him—leaving him hung over and pissed off.

Bondi was already beginning to regret accepting the job as cinematographer for the film, an indie Western called Steele being financed by a bunch of Houston oilmen. It had sounded like fun—five weeks in Santa Fe, shooting at the Lazy C Movie Ranch, staying in a downtown B and B near the plaza. He’d heard that the director, Luke Desjardin, was “a bit of” a maniac, but he’d worked with maniac directors before and felt he could handle it. But Desjardin had turned out to be not just a lightweight maniac, but a fanatically committed one: a Clase Azul–chugging, Montecristo-smoking, coke-snorting tornado who never seemed to sleep and resented others for doing so.

Two dozen crew were on site—grips, PAs, camera operators, a breakfast caterer, the works. They’d hauled out an RV with AC and a flush toilet. There was no lack of money being spent. A large shade had been erected to keep people out of the July sun, with big coolers of ice water set up on tables. At least the backers weren’t parsimonious—or maybe they’d already figured out that filming without basic comforts in a place so brutally remote might cost them a lot more in the end.

Calibration complete, Bondi stepped back. “Ready to fly,” he said.

Desjardin’s voice was almost as high pitched as a girl’s, and so loud that it cut the desert air like a knife. “About time! The sun’s going to be up in less than five minutes.” He took a deep breath. “Here’s the shot I’m looking for—a long, establishing sweep over these badlands just at the crack of dawn, getting in all that golden light and the long shadows.”

“No problem.”

Bondi’s PA stood next to him, ready with a pair of binoculars. He was the spotter, whose job was to keep track of the drone—as much as was possible—in this landscape. But Bondi had plenty of experience flying drones out of sight, using as guidance the video feed on his handheld console.

“I want you to fly past that peak over there,” said the director. “You see it?”

Bondi did indeed see it—a creepy fifty-foot spire of black rock that looked like a crooked finger pointing into the sky, cut off flat on top. It was about a mile away, across a maze-like terrain of hoodoos and balancing rocks, riddled with dry washes and miniature ravines. Bondi had to admit it was a perfect location. It was also a hellscape like nothing he’d ever seen before.

“I want you to fly over to it, camera looking straight down, then come around in a circle, raise the camera to center on the spire, and speed past it, panning back as you go by. Can you do that?”

“Of course.” This was the shit he got paid for. His only real fear was some mechanical failure that might put the drone down somewhere in that crazy landscape.

“Okay. Roll.”

Bondi fired up the drone and raised it to an altitude of ten feet, paused to make sure its GPS made satellite contact and knew where it was, and then bumped it up to sixty feet, high enough to clear the rock formations. He started it off northward at a medium pace, while Desjardin peered closely over his shoulder at the screen, cigar breath washing over Bondi.

“Go lower.”

Bondi lowered the drone to fifty feet.

“Lower.”

Bondi took it down to forty. This was risky, because many of the hoodoo formations were higher than that. But Bondi had confidence in his ability to navigate through them, and besides, the drone had a radar avoidance system that would stop it from flying into a rock even if he tried it. He normally turned this safety feature off when getting closeups, but in this landscape he decided not to risk it.

“Good… good… that’s it… steady on…,” Desjardin murmured, peering at the screen, watching the footage from the drone’s perspective.

“Lost it,” said the spotter with the binocs.

“No worries,” said Bondi. “I got it under control.”

Christ, what a landscape! It was hard to believe it wasn’t some surrealist painting, all the little balancing rocks and spires and arches and twisty little dry washes casting long shadows. As crazy as Desjardin was, he knew how to get incredible footage: this should be fabulous, totally worth the effort.

The cut-off spire was coming up now. It was so prominent, he figured it had to have a name. He flew past it, then brought the drone around in a long, sweeping turn while smoothly raising the camera as he did so. The lens caught a brief moment of the fiery gleam of the rising sun before centering again on the spire. Bondi knew immediately that he’d nailed it, feeling the sudden adrenaline rush of a shot perfectly executed.

“Okay…,” said Desjardin. “Good… now lower the camera back down to the ground.”

He manipulated the controls and the ground loomed up, a pool of fire in the early morning light.

“Lower,” said Desjardin.

Bondi brought it lower, keeping the camera focused on the ground.

“Wait,” said Desjardin. “What’s that?”

Bondi had seen it, too: something on the ground. But the drone had passed by and it was no longer in view.

“Turn back around,” Desjardin said.

Bondi brought it around and retraced.

“There!” Desjardin said.

Bondi brought the drone to a halt, hovering over a whitish object partially obscured by sand.

“What the fuck? It’s a skull!”

“Yeah,” said Bondi.

“And look, there are some bones, too… See them?”

“I do.”

“It’s a skeleton!” Desjardin said. “Oh my God: someone died out here!”

As Bondi panned back over the scattered remains, he saw nearby a rotten old shirt and a shriveled-up running shoe.

“Take the drone a hundred yards north,” said Desjardin, “and then fly it back over, slow, another hundred yards south. Track the skull with the camera.”

“Yes, but…”

“Just do it!”

Bondi did as he was told, flying the drone past the remains.

“Again! This time, raise the camera slightly to pick up the horizon, then pan across the skeleton as you go past.”

“Um, that’s not a prop,” said Bondi.

“Who the hell cares? It’s perfect!”

Cobb, the AD, spoke up. “Luke, there’s nothing in the script about a skeleton.”

“There will be! I can promise you that!”

Bondi flew past again, panning over the bones.

“Those are human remains out there,” said Cobb. “I mean, are we even going to be able to use this footage?”

“You’re damn right we will. They show shit like this on the news every day! Okay, Bondi: do that pan again. That first take was a little rough.”

The drone’s monitor began beeping and flashing, indicating a low battery. “I should bring it back,” Bondi said.

“I can read a meter, too. It’s still at fifteen percent. We’ve got time for another pass.”

“It’s almost a mile out. We need enough juice to bring it back.”

“Do the pass!”

Bondi didn’t argue; it wasn’t his drone. He did the pass again, but his hand on the camera wheel was trembling slightly and it wasn’t a smooth take.

“One more pass!”

The alarm grew more insistent.

“I need to bring it back,” Bondi said. “Now.”

“One more!”

He sent it back out a hundred yards, then turned it around. Abruptly, the screen went pixelated; the alarm beeped—then blackness. Fifteen seconds later, a stark warning message appeared on the screen. EMERGENCY LANDING EFFECTED.

Bondi lowered the monitor. “We lost it.”

“Get the backup drone.”

“It crashed—remember? We’ve got another one in shipment.”

“What the hell?” Desjardin roared with frustration. “Fuck me!” He stomped around, cursing and yelling, as everyone else stood around looking on in silence. This was not the first time he’d lost it on set.

Finally, he rounded on Bondi. “Well, do you know where it is?”

“I’ve got the GPS coordinates.”

“You saw the message. It didn’t crash; it did an emergency landing. It’s still good. Let’s go get it.”

This was met with silence, until finally Cobb said: “You can’t be serious.”

“What do you mean?” screeched Desjardin, whirling toward the AD.

“In July, hiking a mile into those badlands, with the sun up? It’s already close to a hundred degrees. It’ll be death out there.”

“Who made you the expert?”

But Cobb stood firm. “Don’t take my word for it, Luke—that skeleton says it even better. I, for one, have no wish to join it.” And then, as the director fumed, the AD added: “I think we’d better call the cops.”

HOW MUCH FARTHER?” Supervisory Agent Sharp asked from behind the wheel. His sleepy eyes, half-lidded, looked steadily forward as if he were watching a golf match instead of driving through sagebrush plains a hundred miles from nowhere.

Corrie Swanson checked her phone. Even though they were out of cell range, she had downloaded the Google Earth satellite images of the area ahead of time.

She located their little blue dot. “Another five miles.”

“Five miles,” Sharp repeated. “I guess that means the fun part of the drive’s about to begin.”

Sharp was about as droll as FBI agents came, and she wasn’t sure what he meant by this. She looked out the window at the purple sage and bunchgrass; the faraway blue mountains; and, here and there in the middle distance, patches of badlands: clusters of geological bizarreness—boulders balancing on thin flutes of softer material.

Sharp turned a corner and the vehicle dipped into a declivity she hadn’t realized lay before them—and suddenly they were driving into a forest of those goblin-like rocks, the vehicle heaving and yawing over a dirt road that abruptly turned from bad to bone shattering.

“Jesus!” Corrie said involuntarily, gripping the armrests.

“Now you know why they’re called badlands,” Sharp said, his voice a notch higher now to be heard over the racket.

Instead of answering, Corrie merely hung on. It was one thing to view this kind of bizarre sight from miles away—quite another to drive through it on what was more a track than a road. She’d seen pictures, but they didn’t do the place justice. Some of the rock formations looked like intestines, bulged and coiled. Others were more like monstrous fungi or the papillae of a giant’s tongue, sticking upward in disgusting nodules.

“The locals call these rock formations ‘hoodoos,’” said Sharp.

“It’s like the dark side of the moon,” she said. She glanced into the rear-view mirror, where—far behind—the Evidence Response Team van was creeping along, almost invisible in the dust they were throwing up.

They hit a dry wash that nearly bottomed out the vehicle. Corrie wished he’d slow down, but didn’t dare speak out. Dark side of the moon was an understatement. This was more like the place where, during the creation of the world, God had dumped all His leftover rubbish, the bits and pieces of landscape so deformed and grotesque He couldn’t find a place for them anywhere else.

As they came out of the embankment of yet another dry wash, Corrie was shocked to spy in the distance a small, six-sided wooden hut, made of split logs with a dirt roof.

“That can’t be someone’s residence,” she said. “There’s no life on Mars.” But as they drove farther, she made out a shabby trailer behind the hut, along with some corrals.

“Oh my God,” she said. “Look, someone’s there!” And she pointed toward the figure of a woman who appeared in the doorway of the hut to watch them pass by.

“She’s Navajo,” said Sharp. “We’re in an area called the Checkerboard.”

“Sorry?”

“It’s a long story about land appropriation. But basically, what we have here are alternating square miles of Navajo Nation land, checkerboarded with square miles of federal land. There are some tough old people living out here, off-grid, carrying on the traditional ways. Some of them don’t even speak English.”

“But you haven’t been in this area before—right?”

“Not in this particular area. I’ve been elsewhere in the Checkerboard, as well as Chaco Canyon, about ten miles south.”

Corrie had heard about the amazing ruins of Chaco Canyon, and intended to go there when she had a break from work—and assuming they made it out of this otherworldly place without being abducted by aliens.

Sharp was wearing his usual impeccable blue suit. Corrie, on the other hand, had dressed for the desert—hiking boots, shorts, a light shirt and broad-brimmed hat—and she carried a CamelBak water pod. The only nod to her federal status was the dangling lanyard holding her badge. Sharp, on the other hand, looked like he was about to appear before a congressional inquiry.

As they drove around a particularly large hoodoo rock,

Corrie saw in the distance the white shade tent of the movie crew and their vehicles, including a large RV, parked in a rare flat area among the formations. No one was out and about—she figured they were probably holed up in the RV, staying cool.

“Ready to get your hands dirty again, Special Agent Swanson?” Sharp asked.

“Yes, sir.” She mentally tucked away her amazement at the surrounding landscape.

“Since this is the Checkerboard, we’re going to be liaising with the Navajo Nation Police. Crownpoint is sending us a detective sergeant named Benally.”

“Sort of like a Joe Leaphorn?”

Sharp gave a small smile. “Let’s hope he’s as good as one of Tony Hillerman’s cops. I’ve worked with the Navajo Nation Police before and they’re thoroughly professional. They’re also useful in opening doors, if the need arises.” He paused. “I’m expecting you to take the lead on this case, Agent Swanson.”

She nodded. “Thank you, sir.” This was no surprise: she’d expected from the outset that the case would be hers, and she was grateful. She was still in the two-year probationary period of a newly minted FBI agent and was glad to get away from cold case reviews and endless interviews with stupid, unhelpful witnesses.

Sharp eased their SUV into the open area, pulling up alongside the RV. Getting out felt like colliding into a wall of heat. Three people exited the RV on their arrival, and they gathered in the shade under an open tent. It was late in the afternoon and the heat of the day was, thankfully, abating. The three introduced themselves as Luke Desjardin, the director of the film; the cinematographer, Alex Bondi; and another man named Cobb. Desjardin was wearing a big straw hat with a red bandanna draped underneath, a tie-dyed shirt, and baggy pantaloons. Unshaven and ugly. Bondi was young and comparatively normal looking. Cobb was short and radiated intensity.

“So,” said Corrie, collecting her thoughts and directing her questions to Bondi, who looked like the most promising interlocutor. “We reviewed the video you sent—they’re definitely human remains, and fairly recent. We appreciate your contacting us. Has anyone been to the site yet?”

“No,” said Bondi. “We thought we’d wait for you.”

“Good decision,” said Corrie. “And you say you have a GPS location?”

“Yes.” Bondi pointed. “You see that black formation out there? The remains the drone spotted are scattered about fifty yards southeast of it. Our drone ran out of juice and did an emergency landing nearby.”

“Right.” Corrie scanned the forbidding landscape. The black spire—other similarly evil-looking needles of rock dotted the landscape, but it was by far the closest—looked about a mile away. They’d have to work quickly before it got dark. “Can we drive there?”

“I’m afraid not,” Bondi said. “And no trails, either. You’re going to have to hike cross-country.”

Corrie nodded. Hiking would be a bitch, but at least the air was beginning to cool off. She recited to herself the FBI motto: Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity.

The ERT van now arrived in a huge cloud of dust, parking next to their SUV. The doors opened and the team hopped out and began unloading equipment. A few minutes later, they came into the shade of the tent: two ERT technicians and their supervisor, an evidence specialist named Cliff Gradinski. Corrie hadn’t worked with Gradinski before, and Sharp had seemed reticent to answer her questions about the man. She looked him over—a thin figure in his forties, with short brown hair, narrow blue eyes, a pencil neck, and a smooth tan face, carrying what she thought was a satisfied, superior expression.

Introductions complete, Corrie prepared to address the group. Gradinski beat her to it. “All right, everyone, listen up. We’ve got two hours to sunset, so we’ll have to work fast.”

His voice was deep and full of self-regard, and Corrie found herself mildly irritated—she was technically his superior, the agent in charge. She glanced at Sharp and saw something glimmer in his eyes—amusement? Or perhaps a challenge? She pushed down hard on her feeling of irritation, telling herself this was an evidence-gathering expedition and it was normal for the agent to take a back seat and let the evidence professionals do their thing.

“Hats, water, and equipment—check,” Gradinski went on. “Grab your gear, people, and let’s go.”

Corrie shouldered her backpack, which contained her notebook, pencil, FBI-issued camera, small first aid kit, headlamp, compass, and water pod. Then she glanced at Sharp. “You’re not coming?”

“Dressed like this?” he murmured with a sleepy grin, gesturing at his blue suit, white shirt, and black shoes. “I’m going to wait here in the shade for the detective sergeant. It’s your case, Agent Swanson. Good luck.”

GRADINSKI LED THE way, heading toward the prominent landmark, the spire of black rock. The others fell in line behind and started along the hard, dry wash, weaving among the strange hoodoo rocks and sandstone spires of the badlands. The sun cast long shadows. It was still hot, but they made good time—better than Corrie had anticipated. In twenty minutes, they arrived.

“All right, men, let’s get to work,” said Gradinski.

Men. Corrie felt her irritation rise again, but she kept her mouth shut and focused on the site.

The skull and assorted bones lay in a gravelly swale that extended to the base of what people were calling the witch’s finger. There was a scattering of prickly pear cacti, shriveled from dryness, and some other desert plan. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...