- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

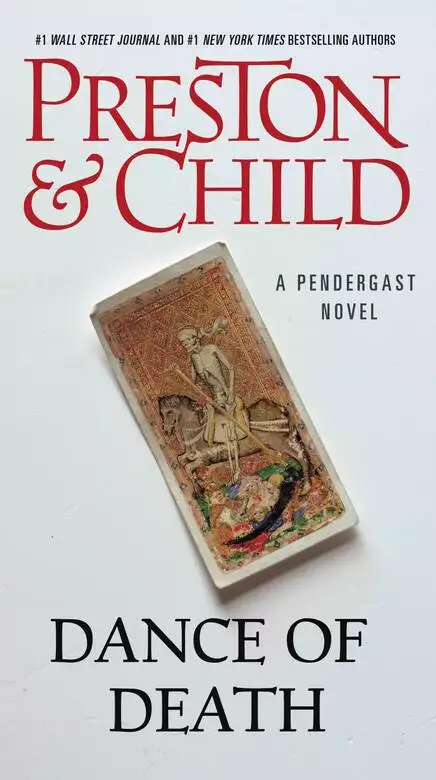

Synopsis

Two brothers.

One a top FBI agent.

The other a brilliant, twisted criminal.

An undying hatred between them.

Now, a perfect crime.

And the ultimate challenge:

Stop me if you can...

Release date: June 1, 2005

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Dance of Death

Douglas Preston

One

DEWAYNE MICHAELS SAT in the second row of the lecture hall, staring at the professor with what he hoped passed for interest. His eyelids were so heavy they felt as if lead sinkers had been sewn to them. His head pounded in rhythm with his heart and his tongue tasted like something had curled up and died on it. He’d arrived late, only to find the huge hall packed and just one seat available: second row center, smack-dab in front of the lectern.

Just great.

Dewayne was majoring in electrical engineering. He’d elected this class for the same reason engineering students had done so for three decades—it was a gimme. “English Literature—A Humanist Perspective” had always been a course you could breeze through and barely crack a book. The usual professor, a fossilized old turd named Mayhew, droned on like a hypnotist, hardly ever looking up from his forty-year-old lecture notes, his voice perfectly pitched for sleeping. The old fart never even changed his exams, and copies were all over Dewayne’s dorm. Just his luck, then, that—for this one semester—a certain renowned Dr. Torrance Hamilton was teaching the course. It was as if Eric Clapton had agreed to play the junior prom, the way they fawned over Hamilton.

Dewayne shifted disconsolately. His butt had already fallen asleep in the cold plastic seat. He glanced to his left, to his right. All around, students—upperclassmen, mostly—were typing notes, running microcassette recorders, hanging on the professor’s every word. It was the first time ever the course had been filled to capacity. Not an engineering student in sight.

What a crock.

Dewayne reminded himself he still had a week to drop the course. But he needed this credit and it was still possible Professor Hamilton was an easy grader. Hell, all these students wouldn’t have shown up on a Saturday morning if they thought they were going to get reamed out . . . would they?

In the meantime, front and center, Dewayne figured he’d better make an effort to look awake.

Hamilton walked back and forth on the podium, his deep voice ringing. He was like a gray lion, his hair swept back in a mane, dressed in a snazzy charcoal suit instead of the usual threadbare set of tweeds. He had an unusual accent, not local to New Orleans, certainly not Yankee. Didn’t exactly sound English, either. A teaching assistant sat in a chair behind the professor, assiduously taking notes.

“And so,” Dr. Hamilton was saying, “today we’re looking at Eliot’s The Waste Land—the poem that packaged the twentieth century in all its alienation and emptiness. One of the greatest poems ever written.”

The Waste Land. Dewayne remembered now. What a title. He hadn’t bothered to read it, of course. Why should he? It was a poem, not a damn novel: he could read it right now, in class.

He picked up the book of T. S. Eliot’s poems—he’d borrowed it from a friend, no use wasting good money on something he’d never look at again—and opened it. There, next to the title page, was a photo of the man himself: a real weenie, tiny little granny glasses, lips pursed like he had two feet of broomstick shoved up his ass. Dewayne snorted and began turning pages. Waste Land, Waste Land . . . here it was.

Oh, shit. This was no limerick. The son of a bitch went on for page after page.

“The first lines are by now so well known that it’s hard for us to imagine the sensation—the shock—that people felt upon first reading it in The Dial in 1922. This was not what people considered poetry. It was, rather, a kind of anti-poem. The persona of the poet was obliterated. To whom belong these grim and disturbing thoughts? There is, of course, the famously bitter allusion to Chaucer in the opening line. But there is much more going on here. Reflect on the opening images: ‘lilacs out of the dead land,’ ‘dull roots,’ ‘forgetful snow.’ No other poet in the history of the world, my friends, ever wrote about spring in quite this way before.”

Dewayne flipped to the end of the poem, found it contained over four hundred lines. Oh, no. No . . .

“It’s intriguing that Eliot chose lilacs in the second line, rather than poppies, which would have been a more traditional choice at the time. Poppies were then growing in an abundance Europe hadn’t seen for centuries, due to the numberless putrefying corpses from the Great War. But more important, the poppy—with its connotations of narcotic sleep—seems the better fit to Eliot’s imagery. So why did Eliot choose lilacs? Let’s take a look at Eliot’s use of allusion, here most likely involving Whitman’s ‘When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.’”

Oh, my God, it was like a nightmare: here he was in the front of the class and not understanding a word the professor was saying. Who’d have thought you could write four hundred lines of poetry on a freaking waste land? Speaking of wasted, his head felt like it was packed full of ball bearings. Served him right for hanging out until four last night, doing shots of citron Grey Goose.

He realized the class around him had gone still, and that the voice from behind the lectern had fallen silent. Glancing up at Dr. Hamilton, he noticed the professor was standing motionless, a strange expression on his face. Elegant or not, the old fellow looked as if he’d just dropped a steaming loaf in his drawers. His face had gone strangely slack. As Dewayne watched, Hamilton slowly withdrew a handkerchief, carefully patted his forehead, then folded the handkerchief neatly and returned it to his pocket. He cleared his throat.

“Pardon me,” he said as he reached for a glass of water on the lectern, took a small sip. “As I was saying, let’s look at the meter Eliot employs in this first section of the poem. His free verse is aggressively enjambed: the only stopped lines are those that finish his sentences. Note also the heavy stressing of verbs: breeding, mixing, stirring. It’s like the ominous, isolated beat of a drum; it’s ugly; it shatters the meaning of the phrase; it creates a sense of disquietude. It announces to us that something’s going to happen in this poem, and that it won’t be pretty.”

The curiosity that had stirred in Dewayne during the unexpected pause faded away. The oddly stricken look had left the professor’s face as quickly as it came, and his features—though still pale—had lost their ashen quality.

Dewayne returned his attention to the book. He could quickly scan the poem, figure out what the damn thing meant. He glanced at the title, then moved his eye down to the epigram, or epigraph, or whatever you called it.

He stopped. What the hell was this? Nam Sibyllam quidem . . . Whatever it was, it wasn’t English. And there, buried in the middle of it, some weird-ass squiggles that weren’t even part of the normal alphabet. He glanced at the explanatory notes at the bottom of the page and found the first bit was Latin, the second Greek. Next came the dedication: For Ezra Pound, il miglior fabbro. The notes said that last bit was Italian.

Latin, Greek, Italian. And the frigging poem hadn’t even started yet. What next, hieroglyphics?

It was a nightmare.

He scanned the first page, then the second. Gibberish, plain and simple. “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” What was that supposed to mean? His eye fell on the next line. Frisch weht der Wind . . .

Abruptly, Dewayne closed the book, feeling sick. That did it. Only thirty lines into the poem and already five damn languages. First thing tomorrow morning, he’d go down to the registrar and drop this turkey.

He sat back, head pounding. Now that the decision was made, he wondered how he was going to make it through the next forty minutes without climbing the walls. If only there’d been a seat up in the back, where he could slip out unseen . . .

Up at the podium, the professor was droning on. “All that being said, then, let’s move on to an examination of—”

Suddenly, Hamilton stopped once again.

“Excuse me.” His face went slack again. He looked—what? Confused? Flustered? No: he looked scared.

Dewayne sat up, suddenly interested.

The professor’s hand fluttered up to his handkerchief, fumbled it out, then dropped it as he tried to bring it to his forehead. He looked around vaguely, hand still fluttering about, as if to ward off a fly. The hand sought out his face, began touching it lightly, like a blind person. The trembling fingers palpated his lips, eyes, nose, hair, then swatted the air again.

The lecture hall had gone still. The teaching assistant in the seat behind the professor put down his pen, a concerned look on his face. What’s going on? Dewayne wondered. Heart attack?

The professor took a small, lurching step forward, bumping into the podium. And now his other hand flew to his face, feeling it all over, only harder now, pushing, stretching the skin, pulling down the lower lip, giving himself a few light slaps.

The professor suddenly stopped and scanned the room. “Is there something wrong with my face?”

Dead silence.

Slowly, very slowly, Dr. Hamilton relaxed. He took a shaky breath, then another, and gradually his features relaxed. He cleared his throat.

“As I was saying—”

Dewayne saw the fingers of one hand come back to life again, twitching, trembling. The hand returned to his face, the fingers plucking, plucking the skin.

This was too weird.

“I—” the professor began, but the hand interfered with his speech. His mouth opened and closed, emitting nothing more than a wheeze. Another shuffled step, like a robot, bumping into the podium.

“What are these things?” he asked, his voice cracking.

God, now he was pulling at his skin, eyelids stretched grotesquely, both hands scrabbling—then a long, uneven scratch from a fingernail, and a line of blood appeared on one cheek.

A ripple coursed through the classroom, like an uneasy sigh.

“Is there something wrong, Professor?” the T.A. said.

“I . . . asked . . . a question.” The professor growled it out, almost against his will, his voice muffled and distorted by the hands pulling at his face.

Another lurching step, and then he let out a sudden scream: “My face! Why will no one tell me what’s wrong with my face!”

More deathly silence.

The fingers were digging in, the fist now pounding at the nose, which cracked faintly.

“Get them off me! They’re eating into my face!”

Oh, shit: blood was now gushing from the nostrils, splashing down on the white shirt and charcoal suit. The fingers were like claws on the face, ripping, tearing; and now one finger hooked up and—Dewayne saw with utter horror—worked itself into one eye socket.

“Out! Get them out!”

There was a sharp, rotating motion that reminded Dewayne of the scooping of ice cream, and suddenly the globe of the eye bulged out, grotesquely large, jittering, staring directly at Dewayne from an impossible angle.

Screams echoed across the lecture hall. Students in the front row recoiled. The T.A. jumped from his seat and ran up to Hamilton, who violently shrugged him off.

Dewayne found himself rooted to his seat, his mind a blank, his limbs paralyzed.

Professor Hamilton now took a mechanical step, and another, ripping at his face, tearing out clumps of hair, staggering as if he might fall directly on top of Dewayne.

“A doctor!” the T.A. screamed. “Get a doctor!”

The spell was broken. There was a sudden commotion, everyone rising at once, the sound of falling books, a loud hubbub of panicked voices.

“My face!” the professor shrieked over the din. “Where is it?”

Chaos took over, students running for the door, some crying. Others rushed forward, toward the stricken professor, jumping onto the podium, trying to stop his murderous self-assault. The professor lashed out at them blindly, making a high-pitched, keening sound, his face a mask of red. Someone forcing his way down the row trod hard on Dewayne’s foot. Drops of flying blood had spattered Dewayne’s face: he could feel their warmth on his skin. Yet still he did not move. He found himself unable to take his eyes off the professor, unable to escape this nightmare.

The students had wrestled the professor to the surface of the podium and were now sliding about in his blood, trying to hold down his thrashing arms and bucking body. As Dewayne watched, the professor threw them off with demonic strength, grabbed the cup of water, smashed it against the podium, and—screaming—began to work the shards into his own neck, twisting and scooping, as if trying to dig something out.

And then, quite suddenly, Dewayne found he could move. He scrambled to his feet, skidded, ran along the row of seats to the aisle, and began sprinting up the stairs toward the back exit of the lecture hall. All he could think about was getting away from the unexplainable horror of what he’d just witnessed. As he shot out the door and dashed full speed down the corridor beyond, one phrase kept echoing in his mind, over and over and over:

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Two

VINNIE? VIN? Sure you don’t want any help in there?”

“No!” Lieutenant Vincent D’Agosta tried to keep his voice cool and even. “No. It’s all right. Just a couple more minutes.”

He glanced up at the clock: almost nine. A couple more minutes. Yeah, right. He’d be lucky if he had dinner on the table by ten.

Laura Hayward’s kitchen—he still thought of it as hers; he’d only moved in six weeks before—was usually an oasis of order, as calm and immaculate as Hayward herself. Now the place looked like a war zone. The sink was overflowing with soiled pots. Half a dozen empty cans lay in and around the wastebasket, dribbling out remnants of tomato sauce and olive oil. Almost as many cookbooks lay open on the counter, their pages obscured by bread crusts and blizzards of flour. The lone window looking down on the snowy intersection of 77th and First was speckled with grease from frying sausages. Although the vent fan was going full blast, the odor of burned meat lingered stubbornly in the air.

For weeks now, whenever their schedules allowed time with each other, Laura had thrown together—almost effortlessly, it seemed—meal after delicious meal. D’Agosta had been astonished. For his soon-to-be-ex-wife, now up in Canada, cooking had always been an ordeal accompanied by histrionic sighs, clanging of pans, and—more often than not—disagreeable results. It was like night and day with Laura.

But along with his astonishment, D’Agosta also felt a bit threatened. As a detective captain in the NYPD, not only did Laura Hayward outrank him, but she outcooked him as well. Everybody knew men made the best chefs, especially Italians. They blew the French out of the water. And so he’d kept promising to cook her a real Italian dinner, just like his grandmother used to make. Each time he repeated the promise, the meal seemed to grow in complexity and spectacle. And at last, tonight was the night he would cook his grandmother’s lasagna napoletana.

Except that once he got in the kitchen, he realized he didn’t remember exactly how his grandmother cooked lasagna napoletana. Oh, he’d watched dozens of times. He’d often helped out. But what precisely went into that ragù she spooned over the layers of pasta? And what was it she’d added to those tiny meatballs that—along with the sausage and various cheeses—made up the filling? He had turned in his desperation to Laura’s cookbooks, but each one had offered conflicting suggestions. And so now here he was, hours later, everything at varying stages of completion, frustration mounting by the second.

He heard Laura say something from her banishment in the living room. He took a deep breath.

“What was that, babe?”

“I said I’ll be home late tomorrow. Rocker’s having a state-of-the-force meeting with all the captains on January 22. That leaves me only Monday evening to get status reports and personnel records up to date.”

“Rocker and his paperwork. How is your pal the commissioner, by the way?”

“He’s not my pal.”

D’Agosta turned back to the ragù, boiling away on the stove. He remained convinced that he’d gotten his old job on the force back, his seniority restored, only because Laura had put a word in Rocker’s ear. He didn’t like it, but there it was.

A huge bubble of ragù rose from the pot, burst like a volcanic eruption, and spewed sauce over his hand. “Ouch!” he cried, dousing the hand in dishwater while turning down the flame.

“What’s up?”

“Nothing. Everything’s just fine.” He stirred the sauce with a wooden spoon, realized the bottom had burned, moved it hastily onto a back burner. He raised the spoon to his lips a little gingerly. Not bad, not bad at all. Decent texture, nice mouth feel, only a slight burned taste. Not like his grandmother’s, though.

“What else goes in the ragù, Nonna?” he murmured.

If there was any response from the choir invisible, D’Agosta couldn’t hear it.

Suddenly, there was a loud hissing from the stove. The giant pot of salted water was bubbling over. Swallowing a curse, D’Agosta turned down the heat on that as well, tore open a box of pasta, dumped in a pound of lasagna.

The sound of music filtered in from the living room: Laura had put on a Steely Dan CD. “I swear I’m going to speak to the landlord about that doorman,” she said through the door.

“Which doorman?”

“That new one who came on a few weeks ago. He’s the surliest guy I’ve ever met. What kind of a doorman doesn’t even open the door for you? And this morning he wouldn’t call me a cab. Just shook his head and walked away. I don’t think he speaks English. At least, he pretends he doesn’t.”

What do you expect for twenty-five hundred a month? D’Agosta thought to himself. But it was her apartment, so he kept his mouth shut. And it was her money that paid the rent—at least for now. He was determined to change that as soon as possible.

When he’d moved in, he hadn’t brought any expectations with him. He’d just gone through one of the worst times in his life, and he refused to let himself think more than a day ahead. Also, he was still in the early stages of what promised to be an unpleasant divorce: a new romantic entanglement probably wasn’t the smartest thing for him right now. But this had turned out far better than he could ever have hoped. Laura Hayward was more than a girlfriend or lover—she’d become a soulmate. He’d thought that their both being on the job, her ranking him, would be a problem. It was just the opposite: it gave them common ground, a chance to help each other, to talk about their cases without worrying about confidentiality or second-guessers.

“Any new leads on the Dangler?” he heard Laura ask from the living room.

The Dangler was the NYPD’s pet name for a perp who’d recently been stealing money from ATMs with a hacked bank card, then exposing his johnson to the security camera. Most of the incidents had been in D’Agosta’s precinct.

“Got a possible eyewitness to yesterday’s job.”

“Eyewitness to what?” Laura asked suggestively.

“To the face, of course.” D’Agosta gave the pasta a stir, regulated the boil. He glanced at the oven, made sure it was up to temperature. Then he turned back to the messy counter, mentally going over everything. Sausage: check. Meatballs: check. Ricotta, Parmesan, and mozzarella fiordilatte: all check. Looks like I might pull this one out of a hat, after all . . .

Hell. He still had to grate the Parmesan.

He threw open a drawer, began rummaging frantically. As he did so, he thought he heard the doorbell ring.

Maybe it was his imagination: Laura didn’t get all that many callers, and he sure as hell didn’t get any. Especially this time of night. It was probably a delivery from the Vietnamese restaurant downstairs, knocking at the wrong door.

His hand closed over the box grater. He yanked it out, set it on the counter, grabbed the brick of Parmesan. He chose the face with the finest grate, raised the Parmesan to the steel.

“Vinnie?” Laura said. “You’d better come out here.”

D’Agosta hesitated only a moment. Something in her tone made him drop everything on the counter and walk out of the kitchen.

She was standing in the front doorway of the apartment, speaking to a stranger. The man’s face was in shadow, and he was dressed in an expensive trench coat. Something about him seemed familiar.

Then the man took a step forward, into the light. D’Agosta caught his breath.

“You!” he said.

The man bowed. “And you are Vincent D’Agosta.”

Laura glanced back at him. Who’s he? her expression read.

Slowly, D’Agosta released the breath. “Laura,” he said, “I’d like you to meet Proctor. Agent Pendergast’s chauffeur.”

Her eyes widened in surprise.

Proctor bowed. “Delighted to make your acquaintance, ma’am.”

She simply nodded in reply.

Proctor turned back to D’Agosta. “Now, sir, if you’d kindly come with me?”

“Where?” But already D’Agosta knew the answer.

“Eight ninety-one Riverside Drive.”

D’Agosta licked his lips. “Why?”

“Because someone is waiting for you there. Someone who has requested your presence.”

“Now?”

Proctor simply bowed again in reply.

Three

D’AGOSTA SAT in the backseat of the vintage ’59 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, looking out the window but not really seeing anything. Proctor had taken him west through the park, and the big car was now rocketing up Broadway.

D’Agosta shifted in the white leather interior, barely able to contain his curiosity and impatience. He was tempted to pepper Proctor with questions, but he felt sure the chauffeur would not respond.

Eight ninety-one Riverside Drive. The home—one of the homes—of Special Agent Aloysius Pendergast, D’Agosta’s friend and partner in several unusual cases. The mysterious FBI agent whom D’Agosta knew, and yet did not know, who seemed to have as many lives as a cat . . .

Until that day not two months ago, when he’d seen Pendergast for the last time.

It had been on the steep flank of a hill south of Florence, Italy. The special agent had been below him, surrounded by a ravening pack of boar-hunting dogs, backed up by a dozen armed men. Pendergast had sacrificed himself so D’Agosta could get away.

And D’Agosta had let him do it.

D’Agosta stirred restlessly at the memory. Someone who has requested your presence, Proctor had said. Was it possible that, despite everything, Pendergast had somehow managed to escape? It wouldn’t be the first time. He suppressed a surge of hope . . .

But no, it was not possible. He knew in his heart that Pendergast was dead.

Now the Rolls was cruising up Riverside Drive. D’Agosta shifted again, glancing out at the passing street signs: 125th Street, 130th. Very quickly, the well-tended neighborhood surrounding Columbia University gave way to dilapidated brownstones and decaying hulks. The usual loiterers had been chased indoors by the January chill, and in the dim light of evening the street looked deserted.

Up ahead now, just past 137th Street, D’Agosta could make out the boarded-up facade and widow’s walk of Pendergast’s mansion. The dark lines of the vast structure sent a chill through him.

The Rolls pulled past the gates of the spiked iron fence and stopped beneath the porte-cochère. Without waiting for Proctor, D’Agosta let himself out and stared up at the familiar lines of the rambling mansion, windows covered with tin, looking for all the world like the other abandoned mansions along the drive. Inside, it was home to wonders and secrets almost beyond belief. He felt his heart begin to race. Maybe Pendergast was inside, after all, in his usual black suit, sitting in the library before a blazing fire, the dancing flames casting strange shadows over his pale face. “My dear Vincent,” he would say, “thank you for coming. May I interest you in a glass of Armagnac?”

D’Agosta waited as Proctor unlocked, then opened, the heavy door. Pale yellow light streamed out onto the worn brickwork. He stepped forward while Proctor carefully relocked the door behind him. He felt his heart beat still faster. Just being back inside the mansion sent a strange mix of emotions coursing through him: excitement, anxiety, regret.

Proctor turned toward him. “This way, sir, if you please.”

The chauffeur led the way down the length of the gallery and into the blue-domed reception hall. Here, dozens of rippled-glass cabinets displayed an array of fabulous specimens: meteorites, gems, fossils, butterflies. D’Agosta’s eyes stole across the parquet floor to the far side, where the double doors of the library lay open. If Pendergast was waiting for him, that’s where he’d be: sitting in a wing chair, a half-smile playing across his lips, enjoying the effect of this little drama on his friend.

Proctor ushered D’Agosta toward the library. Heart pounding, he stepped through the doors and into the sumptuous room.

The smell of the place was as he remembered it: leather, buckram, a faint hint of woodsmoke. But today there was no fire crackling merrily on the hearth. The room was cold. The inlaid bookshelves, full of leather-bound volumes tooled in gold, were dim and indistinct. Only a single lamp glowed—a Tiffany piece standing on a side table—casting a small pool of light in a vast lake of darkness.

After a moment, D’Agosta made out a form standing beside the table, just outside the circle of light. As he watched, the form advanced toward him across the carpeting. He recognized immediately the young girl as Constance Greene, Pendergast’s ward and assistant. She was perhaps twenty, wearing a long, old-fashioned velvet dress that snugged her slender waist and fell in lines almost to the floor. Despite her obvious youth, her bearing had the poise of a much older woman. And her eyes, too—D’Agosta remembered her strange eyes, full of experience and learning, her speech old-fashioned, even quaint. And then there was that something else, something just the other side of normal, that seemed to cling to her like the antique air that exhaled from her dresses.

Those eyes seemed different today. They looked haunted, dark, heavy with loss . . . and fear?

Constance held out her right hand. “Lieutenant D’Agosta,” she said in a measured tone.

D’Agosta took the hand, uncertain as always whether to shake it or kiss it. He did neither, and after a moment the hand was withdrawn.

Normally, Constance was polite to a fault. But today she simply stood before D’Agosta, without offering him a chair or inquiring after his health. She seemed uncertain. And D’Agosta could guess why. The hope that had been stirring within him began to fade.

“Have you heard anything?” she asked, her voice almost too low to make out. “Anything at all?”

D’Agosta shook his head, the flame of hope dashed out.

Constance held his glance a moment longer. Then she nodded her understanding, her gaze dropping to the floor, her hands fluttering at her sides like confused white moths.

They stood there together in silence for a minute, perhaps two.

Constance raised her eyes again. “It’s foolish for me to continue to hope. More than six weeks have passed without a word.”

“I know.”

“He is dead,” she said, voice even lower.

D’Agosta said nothing.

She roused herself. “That means it is time for me to give you this.” She went to the mantelpiece, took down a small sandalwood box inlaid with mother-of-pearl. A tiny key already in her hand, she unlocked it and, without opening it, held it out toward D’Agosta.

“I have delayed this moment too long already. I felt that there was still a chance he might appear.”

D’Agosta stared at the box. It looked familiar, but for a moment he could not place where he’d seen it before. Then it came to him: it had been in this house, this very room, the previous October. He’d entered the library and disturbed Pendergast in the act of writing a note. The agent had slipped it into this same box. That had been the night before they left on their fateful trip to Italy—the night Pendergast told him about his brother, Diogenes.

“Take it, Lieutenant,” Constance said, her voice breaking. “Please don’t draw this out.”

“Sorry.” D’Agosta gently took the box, opened it. Inside lay a single sheet of heavy cream-colored paper, folded once.

Suddenly, the very last thing D’Agosta wanted to do was to take out that piece of paper. With deep misgivings, he reached for it, opened it, and began to read.

My dear Vincent,

If you are reading this letter, it means that I am dead. It also means I died before I could accomplish a task that, rightfully, belongs to me and no other. That task is preventing my brother, Diogenes, from committing what he once boasted would be the “perfect” crime.

I wish I could tell you more about this crime, but all I know of it is that he has been planning it for many years and that he intends it to be his apotheosis. Whatever this “perfect” crime is, it will be infamous. It will make the world a darker place. Diogenes is a man with exceptional standards. He would not settle for less.

I’m afraid, Vincent, that the task of stopping Diogenes must now fall to you. I cannot tell you how much I regret this. It is something I would not wish on my worst enemy, and especially not on somebody I’ve come to regard as a trusted friend. But it is something I believe you are best equipped to handle. Diogenes’s threat is too amorphous f

DEWAYNE MICHAELS SAT in the second row of the lecture hall, staring at the professor with what he hoped passed for interest. His eyelids were so heavy they felt as if lead sinkers had been sewn to them. His head pounded in rhythm with his heart and his tongue tasted like something had curled up and died on it. He’d arrived late, only to find the huge hall packed and just one seat available: second row center, smack-dab in front of the lectern.

Just great.

Dewayne was majoring in electrical engineering. He’d elected this class for the same reason engineering students had done so for three decades—it was a gimme. “English Literature—A Humanist Perspective” had always been a course you could breeze through and barely crack a book. The usual professor, a fossilized old turd named Mayhew, droned on like a hypnotist, hardly ever looking up from his forty-year-old lecture notes, his voice perfectly pitched for sleeping. The old fart never even changed his exams, and copies were all over Dewayne’s dorm. Just his luck, then, that—for this one semester—a certain renowned Dr. Torrance Hamilton was teaching the course. It was as if Eric Clapton had agreed to play the junior prom, the way they fawned over Hamilton.

Dewayne shifted disconsolately. His butt had already fallen asleep in the cold plastic seat. He glanced to his left, to his right. All around, students—upperclassmen, mostly—were typing notes, running microcassette recorders, hanging on the professor’s every word. It was the first time ever the course had been filled to capacity. Not an engineering student in sight.

What a crock.

Dewayne reminded himself he still had a week to drop the course. But he needed this credit and it was still possible Professor Hamilton was an easy grader. Hell, all these students wouldn’t have shown up on a Saturday morning if they thought they were going to get reamed out . . . would they?

In the meantime, front and center, Dewayne figured he’d better make an effort to look awake.

Hamilton walked back and forth on the podium, his deep voice ringing. He was like a gray lion, his hair swept back in a mane, dressed in a snazzy charcoal suit instead of the usual threadbare set of tweeds. He had an unusual accent, not local to New Orleans, certainly not Yankee. Didn’t exactly sound English, either. A teaching assistant sat in a chair behind the professor, assiduously taking notes.

“And so,” Dr. Hamilton was saying, “today we’re looking at Eliot’s The Waste Land—the poem that packaged the twentieth century in all its alienation and emptiness. One of the greatest poems ever written.”

The Waste Land. Dewayne remembered now. What a title. He hadn’t bothered to read it, of course. Why should he? It was a poem, not a damn novel: he could read it right now, in class.

He picked up the book of T. S. Eliot’s poems—he’d borrowed it from a friend, no use wasting good money on something he’d never look at again—and opened it. There, next to the title page, was a photo of the man himself: a real weenie, tiny little granny glasses, lips pursed like he had two feet of broomstick shoved up his ass. Dewayne snorted and began turning pages. Waste Land, Waste Land . . . here it was.

Oh, shit. This was no limerick. The son of a bitch went on for page after page.

“The first lines are by now so well known that it’s hard for us to imagine the sensation—the shock—that people felt upon first reading it in The Dial in 1922. This was not what people considered poetry. It was, rather, a kind of anti-poem. The persona of the poet was obliterated. To whom belong these grim and disturbing thoughts? There is, of course, the famously bitter allusion to Chaucer in the opening line. But there is much more going on here. Reflect on the opening images: ‘lilacs out of the dead land,’ ‘dull roots,’ ‘forgetful snow.’ No other poet in the history of the world, my friends, ever wrote about spring in quite this way before.”

Dewayne flipped to the end of the poem, found it contained over four hundred lines. Oh, no. No . . .

“It’s intriguing that Eliot chose lilacs in the second line, rather than poppies, which would have been a more traditional choice at the time. Poppies were then growing in an abundance Europe hadn’t seen for centuries, due to the numberless putrefying corpses from the Great War. But more important, the poppy—with its connotations of narcotic sleep—seems the better fit to Eliot’s imagery. So why did Eliot choose lilacs? Let’s take a look at Eliot’s use of allusion, here most likely involving Whitman’s ‘When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.’”

Oh, my God, it was like a nightmare: here he was in the front of the class and not understanding a word the professor was saying. Who’d have thought you could write four hundred lines of poetry on a freaking waste land? Speaking of wasted, his head felt like it was packed full of ball bearings. Served him right for hanging out until four last night, doing shots of citron Grey Goose.

He realized the class around him had gone still, and that the voice from behind the lectern had fallen silent. Glancing up at Dr. Hamilton, he noticed the professor was standing motionless, a strange expression on his face. Elegant or not, the old fellow looked as if he’d just dropped a steaming loaf in his drawers. His face had gone strangely slack. As Dewayne watched, Hamilton slowly withdrew a handkerchief, carefully patted his forehead, then folded the handkerchief neatly and returned it to his pocket. He cleared his throat.

“Pardon me,” he said as he reached for a glass of water on the lectern, took a small sip. “As I was saying, let’s look at the meter Eliot employs in this first section of the poem. His free verse is aggressively enjambed: the only stopped lines are those that finish his sentences. Note also the heavy stressing of verbs: breeding, mixing, stirring. It’s like the ominous, isolated beat of a drum; it’s ugly; it shatters the meaning of the phrase; it creates a sense of disquietude. It announces to us that something’s going to happen in this poem, and that it won’t be pretty.”

The curiosity that had stirred in Dewayne during the unexpected pause faded away. The oddly stricken look had left the professor’s face as quickly as it came, and his features—though still pale—had lost their ashen quality.

Dewayne returned his attention to the book. He could quickly scan the poem, figure out what the damn thing meant. He glanced at the title, then moved his eye down to the epigram, or epigraph, or whatever you called it.

He stopped. What the hell was this? Nam Sibyllam quidem . . . Whatever it was, it wasn’t English. And there, buried in the middle of it, some weird-ass squiggles that weren’t even part of the normal alphabet. He glanced at the explanatory notes at the bottom of the page and found the first bit was Latin, the second Greek. Next came the dedication: For Ezra Pound, il miglior fabbro. The notes said that last bit was Italian.

Latin, Greek, Italian. And the frigging poem hadn’t even started yet. What next, hieroglyphics?

It was a nightmare.

He scanned the first page, then the second. Gibberish, plain and simple. “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” What was that supposed to mean? His eye fell on the next line. Frisch weht der Wind . . .

Abruptly, Dewayne closed the book, feeling sick. That did it. Only thirty lines into the poem and already five damn languages. First thing tomorrow morning, he’d go down to the registrar and drop this turkey.

He sat back, head pounding. Now that the decision was made, he wondered how he was going to make it through the next forty minutes without climbing the walls. If only there’d been a seat up in the back, where he could slip out unseen . . .

Up at the podium, the professor was droning on. “All that being said, then, let’s move on to an examination of—”

Suddenly, Hamilton stopped once again.

“Excuse me.” His face went slack again. He looked—what? Confused? Flustered? No: he looked scared.

Dewayne sat up, suddenly interested.

The professor’s hand fluttered up to his handkerchief, fumbled it out, then dropped it as he tried to bring it to his forehead. He looked around vaguely, hand still fluttering about, as if to ward off a fly. The hand sought out his face, began touching it lightly, like a blind person. The trembling fingers palpated his lips, eyes, nose, hair, then swatted the air again.

The lecture hall had gone still. The teaching assistant in the seat behind the professor put down his pen, a concerned look on his face. What’s going on? Dewayne wondered. Heart attack?

The professor took a small, lurching step forward, bumping into the podium. And now his other hand flew to his face, feeling it all over, only harder now, pushing, stretching the skin, pulling down the lower lip, giving himself a few light slaps.

The professor suddenly stopped and scanned the room. “Is there something wrong with my face?”

Dead silence.

Slowly, very slowly, Dr. Hamilton relaxed. He took a shaky breath, then another, and gradually his features relaxed. He cleared his throat.

“As I was saying—”

Dewayne saw the fingers of one hand come back to life again, twitching, trembling. The hand returned to his face, the fingers plucking, plucking the skin.

This was too weird.

“I—” the professor began, but the hand interfered with his speech. His mouth opened and closed, emitting nothing more than a wheeze. Another shuffled step, like a robot, bumping into the podium.

“What are these things?” he asked, his voice cracking.

God, now he was pulling at his skin, eyelids stretched grotesquely, both hands scrabbling—then a long, uneven scratch from a fingernail, and a line of blood appeared on one cheek.

A ripple coursed through the classroom, like an uneasy sigh.

“Is there something wrong, Professor?” the T.A. said.

“I . . . asked . . . a question.” The professor growled it out, almost against his will, his voice muffled and distorted by the hands pulling at his face.

Another lurching step, and then he let out a sudden scream: “My face! Why will no one tell me what’s wrong with my face!”

More deathly silence.

The fingers were digging in, the fist now pounding at the nose, which cracked faintly.

“Get them off me! They’re eating into my face!”

Oh, shit: blood was now gushing from the nostrils, splashing down on the white shirt and charcoal suit. The fingers were like claws on the face, ripping, tearing; and now one finger hooked up and—Dewayne saw with utter horror—worked itself into one eye socket.

“Out! Get them out!”

There was a sharp, rotating motion that reminded Dewayne of the scooping of ice cream, and suddenly the globe of the eye bulged out, grotesquely large, jittering, staring directly at Dewayne from an impossible angle.

Screams echoed across the lecture hall. Students in the front row recoiled. The T.A. jumped from his seat and ran up to Hamilton, who violently shrugged him off.

Dewayne found himself rooted to his seat, his mind a blank, his limbs paralyzed.

Professor Hamilton now took a mechanical step, and another, ripping at his face, tearing out clumps of hair, staggering as if he might fall directly on top of Dewayne.

“A doctor!” the T.A. screamed. “Get a doctor!”

The spell was broken. There was a sudden commotion, everyone rising at once, the sound of falling books, a loud hubbub of panicked voices.

“My face!” the professor shrieked over the din. “Where is it?”

Chaos took over, students running for the door, some crying. Others rushed forward, toward the stricken professor, jumping onto the podium, trying to stop his murderous self-assault. The professor lashed out at them blindly, making a high-pitched, keening sound, his face a mask of red. Someone forcing his way down the row trod hard on Dewayne’s foot. Drops of flying blood had spattered Dewayne’s face: he could feel their warmth on his skin. Yet still he did not move. He found himself unable to take his eyes off the professor, unable to escape this nightmare.

The students had wrestled the professor to the surface of the podium and were now sliding about in his blood, trying to hold down his thrashing arms and bucking body. As Dewayne watched, the professor threw them off with demonic strength, grabbed the cup of water, smashed it against the podium, and—screaming—began to work the shards into his own neck, twisting and scooping, as if trying to dig something out.

And then, quite suddenly, Dewayne found he could move. He scrambled to his feet, skidded, ran along the row of seats to the aisle, and began sprinting up the stairs toward the back exit of the lecture hall. All he could think about was getting away from the unexplainable horror of what he’d just witnessed. As he shot out the door and dashed full speed down the corridor beyond, one phrase kept echoing in his mind, over and over and over:

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.

Two

VINNIE? VIN? Sure you don’t want any help in there?”

“No!” Lieutenant Vincent D’Agosta tried to keep his voice cool and even. “No. It’s all right. Just a couple more minutes.”

He glanced up at the clock: almost nine. A couple more minutes. Yeah, right. He’d be lucky if he had dinner on the table by ten.

Laura Hayward’s kitchen—he still thought of it as hers; he’d only moved in six weeks before—was usually an oasis of order, as calm and immaculate as Hayward herself. Now the place looked like a war zone. The sink was overflowing with soiled pots. Half a dozen empty cans lay in and around the wastebasket, dribbling out remnants of tomato sauce and olive oil. Almost as many cookbooks lay open on the counter, their pages obscured by bread crusts and blizzards of flour. The lone window looking down on the snowy intersection of 77th and First was speckled with grease from frying sausages. Although the vent fan was going full blast, the odor of burned meat lingered stubbornly in the air.

For weeks now, whenever their schedules allowed time with each other, Laura had thrown together—almost effortlessly, it seemed—meal after delicious meal. D’Agosta had been astonished. For his soon-to-be-ex-wife, now up in Canada, cooking had always been an ordeal accompanied by histrionic sighs, clanging of pans, and—more often than not—disagreeable results. It was like night and day with Laura.

But along with his astonishment, D’Agosta also felt a bit threatened. As a detective captain in the NYPD, not only did Laura Hayward outrank him, but she outcooked him as well. Everybody knew men made the best chefs, especially Italians. They blew the French out of the water. And so he’d kept promising to cook her a real Italian dinner, just like his grandmother used to make. Each time he repeated the promise, the meal seemed to grow in complexity and spectacle. And at last, tonight was the night he would cook his grandmother’s lasagna napoletana.

Except that once he got in the kitchen, he realized he didn’t remember exactly how his grandmother cooked lasagna napoletana. Oh, he’d watched dozens of times. He’d often helped out. But what precisely went into that ragù she spooned over the layers of pasta? And what was it she’d added to those tiny meatballs that—along with the sausage and various cheeses—made up the filling? He had turned in his desperation to Laura’s cookbooks, but each one had offered conflicting suggestions. And so now here he was, hours later, everything at varying stages of completion, frustration mounting by the second.

He heard Laura say something from her banishment in the living room. He took a deep breath.

“What was that, babe?”

“I said I’ll be home late tomorrow. Rocker’s having a state-of-the-force meeting with all the captains on January 22. That leaves me only Monday evening to get status reports and personnel records up to date.”

“Rocker and his paperwork. How is your pal the commissioner, by the way?”

“He’s not my pal.”

D’Agosta turned back to the ragù, boiling away on the stove. He remained convinced that he’d gotten his old job on the force back, his seniority restored, only because Laura had put a word in Rocker’s ear. He didn’t like it, but there it was.

A huge bubble of ragù rose from the pot, burst like a volcanic eruption, and spewed sauce over his hand. “Ouch!” he cried, dousing the hand in dishwater while turning down the flame.

“What’s up?”

“Nothing. Everything’s just fine.” He stirred the sauce with a wooden spoon, realized the bottom had burned, moved it hastily onto a back burner. He raised the spoon to his lips a little gingerly. Not bad, not bad at all. Decent texture, nice mouth feel, only a slight burned taste. Not like his grandmother’s, though.

“What else goes in the ragù, Nonna?” he murmured.

If there was any response from the choir invisible, D’Agosta couldn’t hear it.

Suddenly, there was a loud hissing from the stove. The giant pot of salted water was bubbling over. Swallowing a curse, D’Agosta turned down the heat on that as well, tore open a box of pasta, dumped in a pound of lasagna.

The sound of music filtered in from the living room: Laura had put on a Steely Dan CD. “I swear I’m going to speak to the landlord about that doorman,” she said through the door.

“Which doorman?”

“That new one who came on a few weeks ago. He’s the surliest guy I’ve ever met. What kind of a doorman doesn’t even open the door for you? And this morning he wouldn’t call me a cab. Just shook his head and walked away. I don’t think he speaks English. At least, he pretends he doesn’t.”

What do you expect for twenty-five hundred a month? D’Agosta thought to himself. But it was her apartment, so he kept his mouth shut. And it was her money that paid the rent—at least for now. He was determined to change that as soon as possible.

When he’d moved in, he hadn’t brought any expectations with him. He’d just gone through one of the worst times in his life, and he refused to let himself think more than a day ahead. Also, he was still in the early stages of what promised to be an unpleasant divorce: a new romantic entanglement probably wasn’t the smartest thing for him right now. But this had turned out far better than he could ever have hoped. Laura Hayward was more than a girlfriend or lover—she’d become a soulmate. He’d thought that their both being on the job, her ranking him, would be a problem. It was just the opposite: it gave them common ground, a chance to help each other, to talk about their cases without worrying about confidentiality or second-guessers.

“Any new leads on the Dangler?” he heard Laura ask from the living room.

The Dangler was the NYPD’s pet name for a perp who’d recently been stealing money from ATMs with a hacked bank card, then exposing his johnson to the security camera. Most of the incidents had been in D’Agosta’s precinct.

“Got a possible eyewitness to yesterday’s job.”

“Eyewitness to what?” Laura asked suggestively.

“To the face, of course.” D’Agosta gave the pasta a stir, regulated the boil. He glanced at the oven, made sure it was up to temperature. Then he turned back to the messy counter, mentally going over everything. Sausage: check. Meatballs: check. Ricotta, Parmesan, and mozzarella fiordilatte: all check. Looks like I might pull this one out of a hat, after all . . .

Hell. He still had to grate the Parmesan.

He threw open a drawer, began rummaging frantically. As he did so, he thought he heard the doorbell ring.

Maybe it was his imagination: Laura didn’t get all that many callers, and he sure as hell didn’t get any. Especially this time of night. It was probably a delivery from the Vietnamese restaurant downstairs, knocking at the wrong door.

His hand closed over the box grater. He yanked it out, set it on the counter, grabbed the brick of Parmesan. He chose the face with the finest grate, raised the Parmesan to the steel.

“Vinnie?” Laura said. “You’d better come out here.”

D’Agosta hesitated only a moment. Something in her tone made him drop everything on the counter and walk out of the kitchen.

She was standing in the front doorway of the apartment, speaking to a stranger. The man’s face was in shadow, and he was dressed in an expensive trench coat. Something about him seemed familiar.

Then the man took a step forward, into the light. D’Agosta caught his breath.

“You!” he said.

The man bowed. “And you are Vincent D’Agosta.”

Laura glanced back at him. Who’s he? her expression read.

Slowly, D’Agosta released the breath. “Laura,” he said, “I’d like you to meet Proctor. Agent Pendergast’s chauffeur.”

Her eyes widened in surprise.

Proctor bowed. “Delighted to make your acquaintance, ma’am.”

She simply nodded in reply.

Proctor turned back to D’Agosta. “Now, sir, if you’d kindly come with me?”

“Where?” But already D’Agosta knew the answer.

“Eight ninety-one Riverside Drive.”

D’Agosta licked his lips. “Why?”

“Because someone is waiting for you there. Someone who has requested your presence.”

“Now?”

Proctor simply bowed again in reply.

Three

D’AGOSTA SAT in the backseat of the vintage ’59 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, looking out the window but not really seeing anything. Proctor had taken him west through the park, and the big car was now rocketing up Broadway.

D’Agosta shifted in the white leather interior, barely able to contain his curiosity and impatience. He was tempted to pepper Proctor with questions, but he felt sure the chauffeur would not respond.

Eight ninety-one Riverside Drive. The home—one of the homes—of Special Agent Aloysius Pendergast, D’Agosta’s friend and partner in several unusual cases. The mysterious FBI agent whom D’Agosta knew, and yet did not know, who seemed to have as many lives as a cat . . .

Until that day not two months ago, when he’d seen Pendergast for the last time.

It had been on the steep flank of a hill south of Florence, Italy. The special agent had been below him, surrounded by a ravening pack of boar-hunting dogs, backed up by a dozen armed men. Pendergast had sacrificed himself so D’Agosta could get away.

And D’Agosta had let him do it.

D’Agosta stirred restlessly at the memory. Someone who has requested your presence, Proctor had said. Was it possible that, despite everything, Pendergast had somehow managed to escape? It wouldn’t be the first time. He suppressed a surge of hope . . .

But no, it was not possible. He knew in his heart that Pendergast was dead.

Now the Rolls was cruising up Riverside Drive. D’Agosta shifted again, glancing out at the passing street signs: 125th Street, 130th. Very quickly, the well-tended neighborhood surrounding Columbia University gave way to dilapidated brownstones and decaying hulks. The usual loiterers had been chased indoors by the January chill, and in the dim light of evening the street looked deserted.

Up ahead now, just past 137th Street, D’Agosta could make out the boarded-up facade and widow’s walk of Pendergast’s mansion. The dark lines of the vast structure sent a chill through him.

The Rolls pulled past the gates of the spiked iron fence and stopped beneath the porte-cochère. Without waiting for Proctor, D’Agosta let himself out and stared up at the familiar lines of the rambling mansion, windows covered with tin, looking for all the world like the other abandoned mansions along the drive. Inside, it was home to wonders and secrets almost beyond belief. He felt his heart begin to race. Maybe Pendergast was inside, after all, in his usual black suit, sitting in the library before a blazing fire, the dancing flames casting strange shadows over his pale face. “My dear Vincent,” he would say, “thank you for coming. May I interest you in a glass of Armagnac?”

D’Agosta waited as Proctor unlocked, then opened, the heavy door. Pale yellow light streamed out onto the worn brickwork. He stepped forward while Proctor carefully relocked the door behind him. He felt his heart beat still faster. Just being back inside the mansion sent a strange mix of emotions coursing through him: excitement, anxiety, regret.

Proctor turned toward him. “This way, sir, if you please.”

The chauffeur led the way down the length of the gallery and into the blue-domed reception hall. Here, dozens of rippled-glass cabinets displayed an array of fabulous specimens: meteorites, gems, fossils, butterflies. D’Agosta’s eyes stole across the parquet floor to the far side, where the double doors of the library lay open. If Pendergast was waiting for him, that’s where he’d be: sitting in a wing chair, a half-smile playing across his lips, enjoying the effect of this little drama on his friend.

Proctor ushered D’Agosta toward the library. Heart pounding, he stepped through the doors and into the sumptuous room.

The smell of the place was as he remembered it: leather, buckram, a faint hint of woodsmoke. But today there was no fire crackling merrily on the hearth. The room was cold. The inlaid bookshelves, full of leather-bound volumes tooled in gold, were dim and indistinct. Only a single lamp glowed—a Tiffany piece standing on a side table—casting a small pool of light in a vast lake of darkness.

After a moment, D’Agosta made out a form standing beside the table, just outside the circle of light. As he watched, the form advanced toward him across the carpeting. He recognized immediately the young girl as Constance Greene, Pendergast’s ward and assistant. She was perhaps twenty, wearing a long, old-fashioned velvet dress that snugged her slender waist and fell in lines almost to the floor. Despite her obvious youth, her bearing had the poise of a much older woman. And her eyes, too—D’Agosta remembered her strange eyes, full of experience and learning, her speech old-fashioned, even quaint. And then there was that something else, something just the other side of normal, that seemed to cling to her like the antique air that exhaled from her dresses.

Those eyes seemed different today. They looked haunted, dark, heavy with loss . . . and fear?

Constance held out her right hand. “Lieutenant D’Agosta,” she said in a measured tone.

D’Agosta took the hand, uncertain as always whether to shake it or kiss it. He did neither, and after a moment the hand was withdrawn.

Normally, Constance was polite to a fault. But today she simply stood before D’Agosta, without offering him a chair or inquiring after his health. She seemed uncertain. And D’Agosta could guess why. The hope that had been stirring within him began to fade.

“Have you heard anything?” she asked, her voice almost too low to make out. “Anything at all?”

D’Agosta shook his head, the flame of hope dashed out.

Constance held his glance a moment longer. Then she nodded her understanding, her gaze dropping to the floor, her hands fluttering at her sides like confused white moths.

They stood there together in silence for a minute, perhaps two.

Constance raised her eyes again. “It’s foolish for me to continue to hope. More than six weeks have passed without a word.”

“I know.”

“He is dead,” she said, voice even lower.

D’Agosta said nothing.

She roused herself. “That means it is time for me to give you this.” She went to the mantelpiece, took down a small sandalwood box inlaid with mother-of-pearl. A tiny key already in her hand, she unlocked it and, without opening it, held it out toward D’Agosta.

“I have delayed this moment too long already. I felt that there was still a chance he might appear.”

D’Agosta stared at the box. It looked familiar, but for a moment he could not place where he’d seen it before. Then it came to him: it had been in this house, this very room, the previous October. He’d entered the library and disturbed Pendergast in the act of writing a note. The agent had slipped it into this same box. That had been the night before they left on their fateful trip to Italy—the night Pendergast told him about his brother, Diogenes.

“Take it, Lieutenant,” Constance said, her voice breaking. “Please don’t draw this out.”

“Sorry.” D’Agosta gently took the box, opened it. Inside lay a single sheet of heavy cream-colored paper, folded once.

Suddenly, the very last thing D’Agosta wanted to do was to take out that piece of paper. With deep misgivings, he reached for it, opened it, and began to read.

My dear Vincent,

If you are reading this letter, it means that I am dead. It also means I died before I could accomplish a task that, rightfully, belongs to me and no other. That task is preventing my brother, Diogenes, from committing what he once boasted would be the “perfect” crime.

I wish I could tell you more about this crime, but all I know of it is that he has been planning it for many years and that he intends it to be his apotheosis. Whatever this “perfect” crime is, it will be infamous. It will make the world a darker place. Diogenes is a man with exceptional standards. He would not settle for less.

I’m afraid, Vincent, that the task of stopping Diogenes must now fall to you. I cannot tell you how much I regret this. It is something I would not wish on my worst enemy, and especially not on somebody I’ve come to regard as a trusted friend. But it is something I believe you are best equipped to handle. Diogenes’s threat is too amorphous f

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved