- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Miriam Beckstein has gotten in touch with her roots and they have nearly strangled her. A young, hip, business journalist in Boston, she discovered (in The Family Trade ) that her family comes from an alternate reality, that she is very well-connected, and that her family is a lot too much like the mafia for comfort.

In addition, starting with the fact that women are family property and required to breed more family members with the unique talent to walk between worlds, she has tried to remain an outsider and her own woman. And start a profitable business in a third world she has discovered, outside the family reach (recounted in The Hidden Family). She fell in love with a distant relative but he's dead, killed saving her life.

There have been murders, betrayals. Now, however, in The Clan Corporate, she may be overreaching. And if she gets caught, death or a fate worse is around the bend. There is for instance the brain-damaged son of the local king who needs a wife. But they'd never make her do that, would they?

A Macmillan Audio production.

Release date: April 1, 2007

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

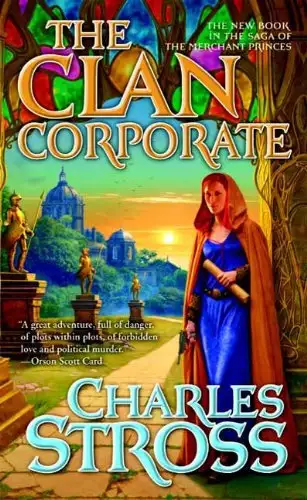

The Clan Corporate

Charles Stross

Tied Down

Nail lacquer, the woman called Helge reflected as she paused in the antechamber, always did two things to her: it reminded her of her mother, and it made her feel like a rebellious little girl. She examined the fingertips of her left hand, turning them this way and that in search of minute imperfections in the early afternoon sunlight slanting through the huge window behind her. There weren't any. The maidservant who had painted them for her had poor nails, cracked and brittle from hard work: her own, in contrast, were pearlescent and glossy, and about a quarter-inch longer than she was comfortable with. There seemed to be a lot of things that she was uncomfortable with these days. She sighed quietly and glanced at the door.

The door opened at that moment. Was it coincidence, or was she being watched? Liveried footmen inclined their heads as another spoke. "Milady, the duchess bids you enter. She is waiting in the day room."

Helge swept past them with a brief nod—more acknowledgment of their presence than most of her rank would bother with—and paused to glance back down the hallway as her servants (a lady-in-waiting, a court butler, and two hard-faced, impassive bodyguards) followed her. "Wait in the hall," she told the guards. "You can accompany me, but wait at the far end of the room," she told her attendant ingénue. Lady Kara nodded meekly. She'd been slow to learn that Helge bore an uncommon dislike for having her conversations eavesdropped on: there had been an unfortunate incident some weeks ago, and the lady-in-waiting had not yet recovered her self-esteem.

The hall was perhaps sixty feet long and wide enough for a royal entourage. The walls, paneled in imported oak, were occupied by window bays interspersed with oil paintings and a few more-recent daguerreotypes of noble ancestors, the scoundrels and skeletons cluttering up the family tree. Uniformed servants waited beside each door. Helge paced across the rough marble tiles, her spine rigid and her shoulders set defensively. At the end of the hall an equerry wearing the polished half-armor and crimson breeches of his calling bowed, then pulled the tasseled bell-pull beside the double doors. "The Countess Helge voh Thorold d'Hjorth!"

The doors opened, ushering Countess Helge inside, leaving servants and guards to cool their heels at the threshold.

The day room was built to classical proportions—but built large, in every dimension. Four windows, each twelve feet high, dominated the south wall, overlooking the regimented lushness of the gardens that surrounded the palace. The ornate plasterwork of the ceiling must have occupied a master and his journeymen for a year. The scale of the architecture dwarfed the merely human furniture, so that the chaise longue the duchess reclined on, and the spindly rococo chair beside it, seemed like the discarded toy furniture of a baby giantess. The duchess herself looked improbably fragile: gray hair growing out in intricately coiffed coils, face powdered to the complexion of a china doll, her body lost in a court gown of black lace over burgundy velvet. But her eyes were bright and alert—and knowing.

Helge paused before the duchess. With a little moue of concentration she essayed a curtsey. "Your grace, I are—am—happy to see you," she said haltingly in hochsprache. "I—I—oh damn." The latter words slipped out in her native tongue. She straightened her knees and sighed. "Well? How am I doing?"

"Hmm." The duchess examined her minutely from head to foot, then nodded slightly. "You're getting better. Well enough to pass tonight. Have a seat." She gestured at the chair beside her.

Miriam sat down. "As long as nobody asks me to dance," she said ruefully. "I've got two left feet, it seems." She plucked at her lap. "And as long as I don't end up being cornered by a drunken backwoods peer who thinks not being fluent in his language is a sign of an imbecile. And as long as I don't accidentally mistake some long-lost third cousin seven times removed for the hat-check clerk and resurrect a two-hundred-year-old blood feud. And as long as—"

"Dear," the duchess said quietly, "do please shut up."

The countess, who had grown up as Miriam but whom everyone around her but the duchess habitually called Helge, stopped in mid-flow. "Yes, Mother," she said meekly. Folding her hands in her lap she breathed out. Then she raised one eyebrow.

The duchess looked at her for almost a minute, then nodded minutely. "You'll pass," she said. "With the jewelry, of course. And the posh frock. As long as you don't let your mouth run away with you." Her cheek twitched. "As long as you remember to be Helge, not Miriam."

"I feel like I'm acting all the time!" Miriam protested.

"Of course you do." The duchess finally smiled. "Imposter syndrome goes with the territory." The smile faded. "And I didn't do you any favors in the long run by hiding you from all this." She gestured around the room. "It becomes harder to adapt, the older you get."

"Oh, I don't know." Miriam frowned momentarily. "I can deal with disguises and a new name and background; I can even cope with trying to learn a new language, it's the sense of permanence that's disconcerting. I grew up an only child, but Helge has all these—relatives—I didn't grow up with, and they're real. That's hard to cope with. And you're here, and part of it!" Her frown returned. "And now this evening's junket. If I thought I could avoid it, I'd be in my rooms having a stomach cramp all afternoon."

"That would be a Bad Idea." The duchess still had the habit of capitalizing her speech when she was waxing sarcastic, Miriam noted.

"Yes, I know that. I'm just—there are things I should be doing that are more important than attending a royal garden party. It's all deeply tedious."

"With an attitude like that you'll go far." Her mother paused. "All the way to the scaffold if you don't watch your lip, at least in public. Do I need to explain how sensitive to social niceties your position here is? This is not America—"

"Yes, well, more's the pity." Miriam shrugged minutely.

"Well, we're stuck with the way things are," the duchess said sharply, then subsided slightly. "I'm sorry, dear, I don't mean to snap. I'm just worried for you. The sooner you learn how to mind yourself without mortally offending anyone by accident the happier I'll be."

"Um." Miriam chewed on the idea for a while. She's stressed, she decided. Is that all it is, or is there something more? "Well, I'll try. But I came here to see how you are, not to have a moan on your shoulder. So, how are you?"

"Well, now that you ask . . ." Her mother smiled and waved vaguely at a table behind her chaise longue. Miriam followed her gesture: two aluminium crutches, starkly functional, lay atop a cloisonné stand next to a pill case. "The doctor says I'm to reduce the prednisone again next week. The Copaxone seems to be helping a lot, and that's just one injection a day. As long as nobody accidentally forgets to bring me next week's prescription I'll be fine."

"But surely nobody would—" Miriam's whole body quivered with anger.

"Really?" The duchess glanced back at her daughter, her expression unreadable. "You seem to have forgotten what kind of a place this is. The meds aren't simply costly in dollars and cents: someone has to bring them across from the other world. And courier time is priceless. Nobody gives me a neatly itemized bill, but if I want to keep on receiving them I have to pay. And the first rule of business around here is, Don't piss off the blackmailers."

Miriam's reluctant nod seemed to satisfy the duchess, because she nodded: "Remember, a lady never unintentionally gives offense—especially to people she depends on to keep her alive. If you can hang on to just one rule to help you survive in the Clan, make it that one. But I'm losing the plot. How are you doing? Have there been any aftereffects?"

"Aftereffects?" Miriam caught her hand at her chin and forced herself to stop fidgeting. She flushed, pulse jerking with an adrenaline surge of remembered fear and anger. "I—" She lowered her hand. "Oh, nothing physical," she said bitterly. "Nothing . . ."

"I've been thinking about him a lot lately, Miriam. He wouldn't have been good for you, you know."

"I know." The younger woman—youth being relative: she wouldn't be seeing thirty again—dropped her gaze. "The political entanglements made it a messy prospect at best," she said, frowning. "Even if you discounted his weaknesses." The duchess didn't reply. Eventually Miriam looked up, her eyes burning with emotions she'd experienced only since learning to be Helge. "I haven't forgiven him, you know."

"Forgiven Roland?" The duchess's tone sharpened.

"No. Your goddamn half-brother. He's meant to be in charge of security! But he—" Her voice began to break.

"Yes, yes, I know. And do you think he has been sleeping well lately? I'm led to believe he's frantically busy right now. Losing Roland was the least of our problems, if you'll permit me to be blunt, and Angbard has a major crisis to deal with. Your affair with him can be ignored, if it comes to it, by the Council. It's not as if you're a teenage virgin to be despoiled, damaging some aristocratic alliance by losing your honor—and you'd better think about that some more in future, because honor is the currency in the circles you move in, a currency that once spent is very hard to regain—but the deeper damage to the Clan that Matthias inflicted—"

"Tell me about it," Miriam said bitterly. "As soon as I was back on my feet they told me I could only run courier assignments to and from a safe house. And I'm not allowed to go home!"

"Matthias knows you," her mother pointed out. "If he mentioned you to his new employers—"

"I understand." Miriam subsided in a sullen silence, arms crossed before her and back set defensively. After a moment she started tapping her toes.

"Stop that!" Moderating her tone, the duchess added, "If you do that in public it sends entirely the wrong message. Appearances are everything, you've got to learn that."

"Yes, Mother."

After a couple of minutes, the duchess spoke. "You're not happy."

"No."

"And it's not just—him."

"Correct." Her hem twitched once more before Helge managed to control the urge to tap.

The duchess sighed. "Do I have to drag it out of you?"

"No, Iris."

"You shouldn't call me that here. Bad habits of thought and behavior, you know."

"Bad? Or just inappropriate? Liable to send the wrong message?"

The duchess chuckled. "I should know better than to argue with you, dear!" She looked serious. "The wrong message in a nutshell. Miriam can't go home, Helge. Not now, maybe not ever. Thanks to that scum-sucking rat-bastard defector the entire Clan network in Massachusetts is blown wide open and if you even think about going—"

"Yeah, yeah, I know, there'll be an FBI SWAT team staking out my backyard and I'll vanish into a supermax prison so fast my feet don't touch the ground. If I'm lucky," she added bitterly. "So everything's locked down like a code-red terrorist alert; the only way I'm allowed to go back to our world is on a closely supervised courier run to an underground railway station buried so deep I don't even see daylight; if I want anything—even a box of tampons—I have to requisition it and someone in the Security Directorate has to fill out a risk assessment to see if it's safe to obtain; and, and . . ." Her shoulders heaved with indignation.

"This is what it was like the whole time, during the civil war," the duchess pointed out.

"So people keep telling me, as if I'm supposed to be grateful! But it's not as if this is my only option. I've got another identity over in world three and—"

"Do they have tampons there?"

"Ah." Helge paused for a moment. "No, I don't think so," she said slowly. "But they've got cotton wool." She fumbled for a moment, then pulled out a pen-sized voice recorder. "Memo: business plans. Investigate early patent filings covering tampons and applicators. Also sterilization methods—dry heat?" She clicked the recorder off and replaced it. "Thanks." A lightning smile that was purely Miriam flashed across her face and was gone. "I should be over there," she added earnestly. "World three is my project. I set up the company and I ought to be managing it."

"Firstly, our dear long-lost relatives are over there," the duchess pointed out. "Truce or not, if they haven't got the message yet, you could show your nose over there and get it chopped off. And secondly . . ."

"Ah, yes. Secondly."

"You know what I'm going to say," the duchess said quietly. "So please don't shoot the messenger."

"Okay." Helge turned her head to stare moodily out of the nearest window. "You're going to tell me that the political situation is messy. That if I go over there right now some of the more jumpy first citizens of the Clan will get the idea that I'm abandoning the sinking ship, aided and abetted by my delightful grandmother's whispering campaign—"

"Leave the rudeness to me. She's my cross to bear."

"Yes, but." Helge stopped.

Her mother took a deep breath. "The Clan, for all its failings, is a very democratic organization. Democratic in the original sense of the word. If enough of the elite voters agree, they can depose the leadership, indict a member of the Clan for trial by a jury of their peers—anything. Which is why appearances, manners, and social standing are so important. Hypocrisy is the grease that lubricates the Clan's machinery." Her cheek twitched. "Oh yes. While I remember, love, if you are accused of anything never, ever, insist on your right to a trial by jury. Over here, that word does not mean what you think it means. Like the word secretary. Pah, but I'm woolgathering! Anyway. My mother, your grandmother, has a constituency, Miri—Helge. Tarnation. Swear at me if I slip again, will you, dear? We need to break each other of this habit."

Helge nodded. "Yes, Iris."

The duchess reached over and swatted her lightly on the arm. "Patricia! Say my full name."

"Ah." Helge met her gaze. "All right. Your grace is the honorable Duchess Patricia voh Hjorth d'Wu ab Thorold." With mild rebellion: "Also known as Iris Beckstein, of 34 Coffin Street—"

"That's enough!" Her mother nodded sharply. "Put the rest behind you for the time being. Until—unless—we can ever go back, the memories can do nothing but hurt you. You've got to live in the present. And the present means living among the Clan and deporting yourself as a, a countess. Because if you don't do that, all the alternatives on offer are drastically worse. This isn't a rich world, like America. Most women only have one thing to trade: as a lady of the Clan you're lucky enough to have two, even three if you count the contents of your head. But if you throw away the money and the power that goes with being of the Clan, you'll rapidly find out just what's under the surface—if you survive long enough."

"But there's no limit to the amount of shit!" the younger woman burst out, then clapped a hand to her face as if to recall the unladylike expostulation.

"Don't chew your nails, dear," her mother said automatically.

It had started in mid-morning. Miriam (who still found it an effort of will to think of herself as Helge, outside of social situations where other people expected her to be Helge) was tired and irritable, dosed up on ibuprofen and propranolol to deal with the effects of a series of courier runs the day before when, wearing jeans and a lined waterproof jacket heavy enough to survive a northeast passage, she'd wheezed under the weight of a backpack and a walking frame. They'd had her ferrying fifty-kilogram loads between a gloomy cellar of undressed stone and an equally gloomy subbasement of an underground car park in Manhattan. There were armed guards in New York to protect her while she recovered from the vicious migraine that world-walking brought on, and there were servants and maids in the palace quarters back home to pamper her and feed her sweetmeats from a cold buffet and apply a cool compress for her head. But the whole objective of all this attention was to soften her up until she could be cozened into making another run. Two return trips in eighteen hours. Drugs or no drugs, it was brutal: without guards and flunkies and servants to prod her along she might have refused to do her duty.

She'd carried a hundred kilograms in each direction across the space between two worlds, a gap narrower than atoms and colder than light-years. Lightning Child only knew what had been in those packages. The Clan's mercantilist operations in the United States emphasized high-value, low-weight commodities. Like it or not, there was more money in smuggling contraband than works of art or intellectual property. It was a perpetual sore on Miriam's conscience, one that only stopped chafing when for a few hours she managed to stop being Miriam Beckstein, journalist, and to be instead Helge of Thorold by Hjorth, Countess. What made it even worse for Miriam was that she was acutely aware that such a business model was stupid and unsustainable. Once, mere weeks ago, she'd had plans to upset the metaphorical applecart, designs to replace it with a fleet of milk tankers. But then Matthias, secretary to the Duke Angbard, captain-general of the Clan's Security Directorate, had upset the applecart first, and set fire to it into the bargain. He'd defected to the Drug Enforcement Agency of the United States of America. And whether or not he'd held his peace about the real nature of the Clan, a dynasty of world-walking spooks from a place where the river of history had run a radically different course, he had sure as hell shut down their eastern seaboard operations.

Matthias had blown more safe houses and shipping networks in one month than the Clan had lost in all the previous thirty years. His psycho bagman had shot and killed Miriam's lover during an attempt to cover up the defection by destroying a major Clan fortress. Then, a month later, Clan security had ordered Miriam back to Niejwein from New Britain, warning that Matthias's allies in that timeline made it too unsafe for her to stay there. Miriam thought this was bullshit: but bullshit delivered by men with automatic weapons was bullshit best nodded along with, at least until their backs were turned.

Mid-morning loomed. Miriam wasn't needed today. She had the next three days off, her corvée paid. Miriam would sleep in, and then Helge would occupy her time with education. Miriam Beckstein had two college degrees, but Countess Helge was woefully uneducated in even the basics of her new life. Just learning how to live among her recently rediscovered extended family was a full-time job. First, language lessons in the hochsprache vernacular with a most attentive tutor, her lady-in-waiting Kara d'Praha. Then an appointment for a fitting with her dressmaker, whose ongoing fabrication of a suitable wardrobe had something of the quality of a Sisyphean task. Perhaps if the weather was good there'd be a discreet lesson in horsemanship (growing up in suburban Boston, she'd never learned to ride): otherwise, one in dancing, deportment, or court etiquette.

Miriam was bored and anxious, itching to get back to her start-up venture in the old capital of New Britain where she'd established a company to build disk brakes and pioneer automotive technology transfer. New Britain was about fifty years behind the world she'd grown up in, a land of opportunity for a sometime tech journalist turned entrepreneur. Helge, however, was strangely fascinated by the minutiae of her new life. Going from middle-class middle-American life to the rarefied upper reaches of a barely postfeudal aristocracy meant learning skills she'd never imagined needing before. She was confronting a divide of five hundred years, not fifty, and it was challenging.

She'd taken the early part of the morning off to be Miriam, sitting in her bedroom in jeans and sweater, her seat a folding aluminum camp chair, a laptop balanced on her knees and a mug of coffee cooling on the floor by her feet. If I can't do I can at least plan, she told herself wryly. She had a lot of plans, more than she knew what to do with. The whole idea of turning the Clan's business model around, from primitive mercantilism to making money off technology transfer between worlds, seemed impossibly utopian—especially considering how few of the Clan elders had any sort of modern education. But without plans, written studies, and costings and risk analyses, she wasn't going to convince anyone. So she'd ground out a couple more pages of proposals before realizing someone was watching her.

"Yes?"

"Milady." Kara bent a knee prettily, a picture of instinctive teenage grace that Miriam couldn't imagine matching. "You bade me remind you last week that this eve is the first of summer twelvenight. There's to be a garden party at the Östhalle tonight, and a ball afterward beside, and a card from her grace your mother bidding you to attend her this afternoon beforehand." Her face the picture of innocence she added, "Shall I attend to your party?"

If Kara organized Helge's carriage and guards then Kara would be coming along too. The memories of what had happened the last time Helge let Kara accompany her to a court event made her want to wince, but she managed to keep a straight face: "Yes, you do that," she said evenly. "Get Mistress Tanzig in to dress me before lunch, and my compliments to her grace my mother and I shall be with her by the second hour of the afternoon." Mistress Tanzig, the dressmaker, would know what Helge should wear in public and, more important, would be able to alter it to fit if there were any last-minute problems. Miriam hit the save button on her spreadsheet and sighed. "Is that the time? Tell somebody to run me a bath; I'll be out in a minute."

So much for the day off, thought Miriam as she packed the laptop away. I suppose I'd better go and be Helge . . .

"Have you thought about marriage?" asked the duchess.

"Mother! As if!" Helge snorted indignantly and her eyes narrowed. "It's been about, what, ten weeks? Twelve? If you think I'm about to shack up with some golden boy so soon after losing Roland—"

"That wasn't what I meant, dear."

Helge drew breath. "What do you mean?"

"I meant . . ." The duchess Patricia glanced at her sharply, taking stock: "The, ah, noble institution. Have you thought about what it means here? And if so, what did you think?"

"I thought"—a slight expression of puzzlement wrinkled Helge's forehead—"when I first arrived, Angbard tried to convince me I ought to make an alliance of fortunes, as he put it. Crudely speaking, to tie myself to a powerful man who could protect me." The wrinkles turned into a full-blown frown. "I nearly told him he could put his alliance right where the sun doesn't shine."

"It's a good thing you didn't," her mother said diplomatically.

"Oh, I know that! Now. But the whole deal here creeps me out. And then." Helge took a deep breath and looked at the duchess: "There's you, your experience. I really don't know how you can stand to be in the same room as her grace your mother, the bitch! How she could—"

"Connive at ending a civil war?" the duchess asked sharply.

"Sell off her daughter to a wife-beating scumbag is more the phrase I had in mind." Helge paused. "Against her wishes," she added. A longer pause. "Well?"

"Well," the duchess said quietly. "Well, well. And well again. Would you like to know how she did it?"

"I'm not sure." A grimace.

"Well, whether you want to or not, I think you need to know," Iris—Patricia, the duchess Patricia, said. "Forewarned is forearmed, and no, when I was your age—and younger—I didn't want to know about it, either. But nobody's offering to trade you on the block like a piece of horseflesh. I should think the worst they'll do is drop broad hints your way and make the consequences of noncooperation irritatingly obvious in the hope you'll give in just to make them go away. You've probably got enough clout to ignore them if you want to push it—if it matters to you enough. But whether it would be wise to ignore them is another question entirely."

"Who are ‘they'?"

"Aha! The right question, at last!" Iris laboriously levered herself upright on her chaise, beaming. "I told you the Clan is democratic, in the classical sense of the word. The marriage market is democracy in action, Helge, and as we all know, Democracy Is Always Right. Yes? Now, can you tell me who, within the family, provides the bride's dowry?"

"Why, the—" Helge thought for a moment. "Well, it's the head of the household's wealth, but doesn't the woman's mother have something to do with determining how much goes into it?"

"Exactly." The duchess nodded. "Braids cross three families, alternating every couple of generations so that issues of consanguinity don't arise but the Clan gift—the recessive gene—is preserved. To organize a braid takes some kind of continuity across at least three generations. A burden which naturally falls on the eldest women of the Clan. Men don't count: men tend to go and get themselves killed fighting silly duels. Or in wars. Or blood feuds. Or they sire bastards who then become part of the outer families and a tiresome burden. They—the bastards—can't world-walk, but some of their issue might, or their grandchildren. So we must keep track of them and find something useful for them to do—unlike the rest of the nobility here we have an incentive to look after our by-blows. I think we're lucky, in that respect, to have a matrilineal succession—other tribal societies I studied in my youth, patrilineal ones, were not nice places to be born female. Whichever and whatever, the lineage is preserved largely by the old women acting in concert. A conspiracy of matchmakers, if you like. The ‘old bitches,' as everyone under sixty tends to call them." The duchess frowned. "It doesn't seem quite as funny now I'm sixty-two."

"Um." Helge leaned toward her mother. "You're telling me Hildegarde wasn't acting alone? Or she was being pressured by her mother? Or what?"

"Oh, she's an evil bitch in her own right," Patricia waved off the question dismissively. "But yes, she was pressured. She and the other ladies of a certain age don't have the two things that a young and eligible Clan lady can bargain with: they can't bear world-walkers, and they can no longer carry heavy loads for the family trade. So they must rely on other, more subtle tools to maintain their position. Like their ability to plait the braids, and to do each other favors, by way of their grandchildren. And when my mother was in her thirties—little older than you are now—she was subjected to much pressure."

"So there's this conspiracy of old women"—Helge was grasping after the concept—"who can make everyone's life a misery?"

"Don't underestimate them," warned the duchess. "They always win in the end, and you'll need to make your peace with them sooner or later. I'm unusual, I managed to evade them for more than three decades. But that almost never happens, and even when it does you can't actually win, because whether you fight them or no, you end up becoming one yourself." She raised one finger in warning. "You're relatively safe, kid. You're too old, too educated, and you've got your own power base. As far as I can see they've got no reason to meddle with you unless you threaten their honor. Honor is survival here. Don't ever do that, Miriam—Helge. If you do, they'll find a way to bring you down. All it takes is leverage, and leverage is the one thing they've got." She smiled thinly. "Think of them as Darwin's revenge on us, and remember to smile and curtsey when you pass them because until you've given them grandchildren they will regard you as an expendable piece to move around the game board. And if you have given them a child, they have a hostage to hold against you."

Mid-afternoon, Helge returned to her rooms to check briefly on the arrangements for her travel to the Östhalle—it being high summer, with the sun setting well after ten o'clock, she need not depart until close to seven—then turned to Lady Kara. "I would like to see Lady Olga, if she's available. Will you investigate? I haven't seen her around lately."

"Lady Olga is in town today. She is down at the battery range," Kara said without blinking. "She told me this morning that you'd be welcome to join her."

Most welcome to—then why didn't you tell me? Helge bit her tongue. Kara probably had some reason for withholding the invitation that had seemed valid at the time. Berating her for not passing on trivial messages would only cause Kara to start dropping every piece of trivia to which she was privy on her mistress's shoulders, rather than risk rebuke. "Then let's go and see her!" Helge said brightly. "It's not far, is it?"

The battery range was near the outer wall of the palace grounds—the summer palace, owned and occupied by those of the Clan elders who needed accommodation in the capital, Niejwein—and separated from those grounds by its own high stone wall. Miriam strolled slowly behind her guards, taking in the warm air and the scent of the ornamental shrubs planted to either side of the path. Her butler held a silk parasol above her to keep the sunlight off her skin. It still felt strange, the whole noble lady shtick, but there were some aspects of it she could live with. She paused at the gate in the wall. From the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...