- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

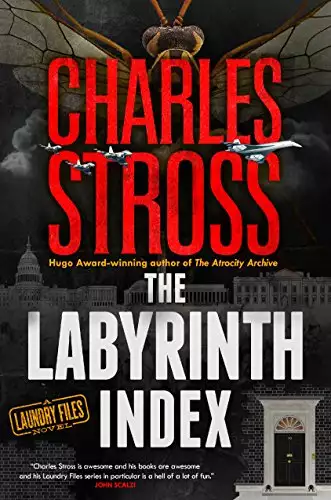

Synopsis

Britain is under New Management. The disbanding of the Laundry — the British espionage agency that deals with supernatural threats — has culminated in the unthinkable: an elder god in residence in 10 Downing Street.

But in true 'the enemy of my enemy' fashion, Mhari Murphy finds herself working with His Excellency Nylarlathotep on foreign policy — there are worse things, it seems, than an elder god in power, and they lie in deepest, darkest America.

A thousand-mile-wide storm system has blanketed the Midwest, and the president is nowhere to be found. Mhari must lead a task force of disgraced Laundry personnel into the storm front to discover the truth. But working for an elder god is never easy, and as the stakes rise, Mhari will soon question exactly where her loyalties really lie.

Release date: October 30, 2018

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Labyrinth Index

Charles Stross

GOD SAVE THE KING

As I cross the courtyard to the execution shed I pass a tangle of bloody feathers. They appear to be the remains of one of the resident corvids, which surprises me because I thought they were already dead. Ravens are powerful and frighteningly astute birds, but they’re no match for the tentacled dragonspawn that the New Management has brought to the Tower of London.

These are strange days and I can’t say I’m happy about all the regime’s decisions—but one does what one must to survive. And rule number one of life under the new regime is, don’t piss Him off.

So I do my best to ignore the pavement pizza, and steel myself for what’s coming next as I enter the shed, where the client is waiting with the witnesses, a couple of prison officers, and the superintendent.

Executions are formal occasions. I’m here as a participant, acting on behalf of my department. So I’m dressed in my funerals-and-court-appearances suit, special briefcase in hand. As I approach the police checkpoint, a constable makes a point of examining my warrant card. Then she matches me against the list of participants and peeks under my veil before letting me inside. Her partner watches the courtyard, helmet visor down and assault rifle at the ready.

The shed has been redecorated several times since they used to shoot spies in it during the Second World War. It’s no longer an indoor shooting range, for one thing. For another, they’ve installed soundproof partitions and walls, so that the entrance opens onto a reception area before the airlock arrangement leading to a long corridor. They sign me in and I proceed past open doors that reveal spotless cells—the unit is very new, and my client today is the first condemned to be processed—then continue on to the doorway to the execution chamber at the end.

The chamber resembles a small operating theater. The table has straps to hold the client down. There’s a one-way window on one wall, behind which I assume the witnesses are already waiting. I pause in the entrance and see, reflected in the mirror, the client staring at the odd whorl of blankness in the doorway.

“Ah, Ms. Murphy.” The superintendent nods at me, mildly aggrieved. “You’re late.” She stands on the far side of the prisoner. She’s in her dress uniform: a formal occasion, as already noted.

“Delays on the Circle Line.” I shrug. “Sorry to hold you up.”

“Yes, well, the prisoner doesn’t get to eat breakfast until we’re finished here.”

I stifle a sigh. “Are we ready to start?” I ask as I place the special briefcase on the side table, then dial in the combination and unlock it.

“Yes.” The superintendent turns to one of the prison officers. “Nigel, if you’d be so good as to talk us through the checklist?”

Nigel clears his throat. “Certainly, ma’am. First, a roll-call for the party. Superintendent: present. Security detail of four: present. Executioner: present—”

The condemned, who has been silent since I arrived, rolls his head sideways to glare at me. It’s all he can move: he’s trussed up like a Christmas turkey. His eyes are brown and liquid, and he has a straggly beard that somehow evades his cheekbones but engulfs his neck, as if he grew it for insulation from the cold. I smile at him as I say, “This won’t hurt.” Then I remember the veil. I flip it back from my face and he flinches.

“Superintendent, please confirm the identity of the subject.”

The superintendent licks her lips. “I hereby confirm that the subject before us today is Mohammed Kadir, as delivered into the custody of this unit on January 12th, 2015.”

“Confirmed. Superintendent, please read the execution warrant.”

She reaches for a large manila envelope on the counter beside the stainless-steel sink, and opens it. There’s a slim document inside, secured with Treasury tags.

“By authority vested in me by order of Her Majesty, Elizabeth II, I hereby uphold and confirm the sentence of death passed on Mohammed Kadir by the High Court on November 25th, 2014, for the crime of High Treason, and upheld on appeal by the Supreme Court on December 5th. Signed and witnessed, Home Secretary…”

When the New Management reintroduced the death penalty, they also reintroduced the British tradition of greasing the skids under the condemned—letting people rot on death row being seen as more cruel than the fate we’re about to inflict on the unfortunate Mr. Kadir. Who, to be fair, probably shouldn’t have babbled fantasies about assassinating the new Prime Minister in front of a directional microphone after Friday prayers during a national state of emergency. Sucks to be him.

“Phlebotomist, please prepare the subject.”

Mr. Kadir is strapped down with his right arm outstretched and the sleeve of his prison sweatshirt rolled up. Now one of the prison officers steps between us and bends over him, carefully probing the crook of his elbow for a vein. Mr. Kadir is not, thankfully, a junkie. He winces once, then the phlebotomist tapes the needle in place and steps back. He side-eyes me on his way. Is he looking slightly green?

“Executioner, proceed.”

This is my cue. I reach into the foam-padded interior of the briefcase for the first sample tube. They’re needle-less syringes, just like the ones your doctor uses for blood tests. I pull ten cubic centimeters of blood into it and cap it. Venous blood isn’t really blue. In lipstick terms it’s dark plum, not crimson gloss. I place the full tube in its recess and take the next one, then repeat the process eighteen times. It’s not demanding work, but it requires a steady hand. In the end it takes me just over ten minutes. During the entire process Mr. Kadir lies still, not fighting the restraints. After the third sample, he closes his eyes and relaxes slightly.

Finally, I’m done. I close and latch the briefcase. The phlebotomist slides out the cannula and holds a ball of cotton wool against the pinprick while he applies a sticking plaster. “There, that didn’t hurt at all, did it?” I smile at Mr. Kadir. “Thank you for your cooperation.”

Mr. Kadir opens his eyes, gives me a deathly stare, and recites the Shahada at me: “la ?ilaha ?illa llah mu?ammadun rasulu llah.” That’s me told.

I smile wider, giving him a flash of my fangs before I tug my veil forward again. He gives no sign of being reassured by my resuming the veil, possibly because he knows I only wear it in lieu of factor-500 sunblock.

I sign the warrant on Nigel’s clipboard. “Executioner, participation concluded,” he intones. And that’s me, done here.

“You can go now,” the superintendent tells me. She looks as if she’s aged a decade in the last quarter of an hour, but is also obscurely relieved: the matter is now out of her hands. “We’ll get Mr. Kadir settled back in his cell and feed him his breakfast once you’ve gone.” I glance at the mirror, at the blind spot reflected mockingly back at me. “The witnesses have a separate exit,” she adds.

“Right.” I nod and take a deep breath. “I’ll just be off, then.” Taking another deep breath, I spin the dials on the briefcase lock and pick it up. “Ta-ta, see you next time.”

I’m a little bit jittery as I leave the execution chamber behind, but there’s a spring in my step and I have to force myself not to click my heels. It all went a lot more smoothly than I expected. The briefcase feels heavier, even though it’s weighed down by less than half an old-school pint. Chateau Kadir, vintage January 2015, shelf life two weeks. I make my way out, head for Tower Bridge Road, and expense an Addison Lee minicab back to headquarters. I can’t wait to get there—I’m absolutely starving, for some reason.

Behind me, the witnesses will have already left. Mr. Kadir is being booked into the cell he will occupy for the next two weeks or so, under suicide watch. I expect the superintendent to look after her dead man with compassion and restraint. He’ll get final meals and visits with his family, an imam who will pray with him, all the solicitous nursing support and at-home palliative care that can be delivered to his cell door for as long as his body keeps breathing. But that’s not my department.

All I know is that in two weeks, give or take, Mr. Kadir, Daesh sympathizer and indiscreet blabbermouth, still walking and talking even though he was executed an hour ago, will be dead of V-syndrome-induced cerebral atrophy. And, as a side effect of the manner of his death, my people, the PHANGs who submitted to the rule of the New Management, will keep on going.

Because the blood is the life.

* * *

Hello, diary. I am Mhari Murphy, and if you are reading this I really hope I’m dead.

I used to work for the Laundry, a government agency that has been in the news for all the wrong reasons lately. I wanted to study biology, but ended up with a BSc in library science, for reasons too long and tedious to explain. Then I ended up with a job in Human Resources at the agency in question. I was a laughably bad fit, so it wasn’t hard to get them to let me transfer out to the private sector. I acquired management experience and studied for my MBA while working for one of our largest investment banks, and was busily climbing the career ladder there when an unfortunate encounter with a contagious meme turned me into a vampire.

As a result of my new status as one of the PHANGs—Persons of Hemphagia-Assisted Neurodegenerative Geheime Staatspolizei (or something like that, the acronym wanders but the blood-drinking remains the same)—I ended up drafted back into the Human Resources Department of Q-Division, Special Operations Executive, aka the Laundry: the secret agency that protects the UK from alien nightmares and magical horrors. But things were different this time round. I was rapidly reassigned to a policing agency called the Transhuman Police Coordination Force, as director of operations and assistant to the chief executive, Dr. O’Brien. Our beat was dealing with superpowered idiots in masks. (The less said about my time as White Mask—a member of the official Home Office superhero team—the better.) When all’s said and done, TPCF was mostly a public relations exercise, but it was a blessing in disguise for me because it broke me out of a career rut. When TPCF was gobbled up by the London Metropolitan Police I was re-acquired by Q-Division, moved onto the management fast-track, and assigned responsibility for the PHANGs. All the surviving ones, that is.

A big chunk of my job is to organize and requisition their blood meals, because the way PHANGs derive sustenance from human blood is extremely ugly. The V-parasites that give us our capabilities rely on us to draw blood from donors. They then chew microscopic holes in the victims’ gray matter, so that they die horribly, sooner rather than later. But if we don’t drink donor blood, eventually our parasites eat us. Consequently, it fell to someone to arrange to procure a steady supply of blood from dying terminal patients and distribute it to the PHANGs. That someone being me.

Anyway, that was the status quo ante, with me responsible for keeping all PHANGs on a very short leash and available for operational duties—they tend to be really good sorcerers, as long as they don’t go insane from hunger and start murdering people—until the horrifying mess in Yorkshire last year resulted in the outing and subsequent dismemberment of the agency.

PHANGs being high-capability assets, I was pulled into Continuity Operations by the Senior Auditor and assigned to Active Ops, a specialty I’ve evaded for the past fifteen years because I do not approve of playing James Bond games when there are documents to be processed and meetings to be chaired. To be honest, I joined Continuity Operations mainly in the expectation that it would keep my team of PHANGs fed. I think most of us would choose to walk into the sunlight if the hunger pangs got too bad, but I’m not exactly keen to test their limits. Neither do I want to murder my own people. So it fell to me to keep them alive by any means necessary.

Continuity Operations—working against an enemy organization that had infiltrated and captured the government behind our back—were entirely necessary. And when the dust settled, we had a new government—the New Management, led by the very shiny new Prime Minister, who was unanimously voted into Westminster by the grateful citizens of a constituency whose former MP (a member of the cabinet) was catatonic in a hospital bed at the time. The Home Secretary invoked the Civil Contingencies Act and served as transitional PM in the wake of the emergency at Nether Stowe House, but she stepped down without a struggle1 right after the new Prime Minister took the oath. Personally I suspect the PM had something to do with her resignation, but I have no proof, and as you have probably realized by now, it is very unwise to ask certain questions about the New Management, lest they ask questions about you.

We are now six months on from the tumultuous scene at the Palace of Westminster, when the Prime Minister took his seat and the New Management presented its program in the Queen’s Speech. Six months into rule by decree under the imprimatur of the Civil Contingencies Act, as Parliament obediently processes a gigantic laundry-list of legislative changes. Six months into an ongoing state of emergency, as the nation finds itself under attack from without and within.

Which brings me to my current job.

Five months ago I was notified that it was Her Majesty’s pleasure—or rather, that of her government—to bestow upon me the rank of Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. That rank came with the title of Baroness Karnstein (the PM’s little joke), a life peerage, and a seat in the House of Lords.

The British government gives good titles, but don’t get too excited: it just means the New Management considers PHANGs to be a useful instrument of state, and wanted a tame expert on board. Consequently I chair the Lords Select Committee on Sanguinary Affairs and have the distasteful duty to conduct executions, newly recommenced after fifty years in abeyance. Although I did get to be the first vampire—as far as I know—ever to wear an ermine-trimmed robe to the state opening of Parliament, so I suppose there’s a silver lining …

Anyway, that’s my CV. A slow start followed by a dizzying stratospheric ascent into government, you might think. But the New Management doesn’t hand out honors and benefices without getting something in return. And I’ve been waiting for the other Jimmy Choo to drop ever since I was sworn in.

* * *

An unwelcome consequence of my new position is that I have come to the attention of very important people. This is a mixed blessing, especially when one of them is the Prime Minister himself, Fabian Everyman, also known as the Mandate—or the People’s Mandate, if you’re a tabloid journalist.

A couple of days after I officiated at the execution of Mr. Kadir—his soul is now feeding the V-parasites of some seven PHANGs, so he’s probably good for another week—I’m alert and not particularly hungry as I perch on the edge of a fussy Victorian sofa in the White Drawing Room at 10 Downing Street.

I’m here because the PM invited me for afternoon tea and cakes along with a handful of colleagues from Mahogany Row, the formerly secretive upper tier of the Laundry. The PM is wearing his usual immaculate three-piece suit, and everyone is on high alert. This session is only informal insofar as it has no agenda. In truth, it’s a platform for the PM, who is mercurial at best, to rant at us about his personal hobby horses. (Which are many and alarming, and he tends to switch between them in mid-sentence.) It’s as exhausting as dealing with an early-stage dementia sufferer—one with a trillion-pound budget and nuclear-weapons-release authority.

“We need to deal with the Jews, you know,” Fabian confides, then pauses dramatically.

This is new and unwelcome, and more than somewhat worrying. (I knew the PM held some rather extreme views, but this level of forthright anti-Semitism is unexpected.) “May I ask why?” I ask hesitantly.

“I’d have thought it was obvious!” He sniffs. “All that charitable work. Loaves and fishes, good Samaritans, y’know. Sermon on the Mount stuff. Can’t be doing with it—”

Beside me, Chris Womack risks interrupting His flow: “Don’t you mean Christians, sir?”

“—And all those suicide bombers. Blowing people up in the name of their god, but can’t choke down a bacon roll. Can’t be doing with them: you mark my words, they’ll have to be dealt with!”

Across the room, Vikram Choudhury nearly swallows his tongue. Chris persists: “But those are Mus—”

“—All Jews!” the Prime Minister snaps. “They’re just the same from where I’m standing.” His expression is one of tight-lipped disapproval—then I blink, and in the time it takes before my eyelids open again, I forget his face. He sips delicately from his teacup, pinkie crooked, then explains His thinking. “Christians, Muslims, Jews—they say they’re different religions, but you mark my words, they all worship the same god, and you know what that leads to if you let it fester. Monotheism is nothing but trouble—unless the one true god is me, of course.” He puts his teacup down and beams at us. “I want a plan on my desk by the beginning of next month to prepare a framework for solving the Jewish problem. Mosques, mikvahs, Christian Science reading rooms: I want them all pinpointed, and a team on the ground drawing up plans to ensure the epidemic spreads no further!”

“A, a final solution?” Vikram asks, utterly aghast.

The PM looks primly shocked. “Absolutely not! What do you take me for? This is the very model of an enlightened and forward-looking government! The indiscriminate slaughter of innocents is wasteful and unappealing—although I’m sure there are some reality TV shows that could use a supply of Hunger Games contestants, ha ha! No, I just want the pernicious virus of the wrong kind of monotheism contained. Starve it of the oxygen of publicity and it’ll suffocate eventually, no need for gas chambers, what?”

“But sir,” Chris speaks up again—unwisely, in my opinion—“we have a legal commitment to religious freedom—”

The PM holds up a hand: “Maybe we do, but they don’t, and if they get out of control again we’ll end up with another Akhenaten. That’s where they get it from, you know—once you allow one god to take over a pantheon and suppress the worship of rivals, it never ends well unless you’re the first mover. But don’t worry about the religious freedom issue! It’ll be taken care of in the Great Repeal Bill I’ve directed the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel to draw up.” He shakes his head dismissively as one of the police officers refills his cup from a brilliantly polished silver teapot. “Now, on a happier note, I’d like to hear how plans are coming along for the Tzompantli that will replace the Marble Arch those idiots erected in place of the Tyburn tree…”

Say whatever else you will about him, Fabian is full of unpleasant and exciting surprises, and always three steps ahead of the rest of us! He reminds me of a certain ex of mine in that respect. But it’s a bad idea to enthusiastically applaud everything the PM comes out with. Sometimes he says outrageous things deliberately to smoke out flatterers and yes-men. The way to survive these sessions is to pay attention to how his inner circle react. So I take my cue from Mrs. Carpenter, his chief of staff, who is nodding along thoughtfully, and match my reactions to hers. And that’s how I get through the next half hour while Hector MacArthur—who has apparently landed the job of coordinating the festivities for Her Majesty’s ninetieth birthday—describes some sort of bizarre titanium and glass sculpture that he asked Foster + Partners to design for the junction of Park Lane and Oxford Street.

Whatever a Tzompantli is, it keeps the PM happy, and that’s never a bad thing. When the PM is unhappy He has a tendency to meddle and break things. Last month it was Prince Charles (no biggie: I gather he should be out of hospital just as soon as he stops weeping uncontrollably); this month it was the US Ambassador (who made the mistake of personally asking for a tax break for his golf course in Ayrshire). From the way He’s talking, next month it could be the Church of England; and then where will we turn for tea, sympathy, and exorcisms?

Finally the fountain of bizarre winds down. “Well, it’s been lovely to see everyone,” the PM assures us, “but I really mustn’t keep you any longer, I’m sure you all have important things to be getting on with!” It’s a dismissal, and we all stand. “Not you, Baroness Karnstein,” He says as the shell-shocked survivors of Mahogany Row file out of the drawing room, “or you, Iris.” The PM smiles, and for a moment I see a flickering vision where His face should be: an onion-skin Matryoshka doll of circular shark-toothed maws, lizard-man faces, and insectile hunger. “A word in my study if you don’t mind. Right this way.”

Oh dear, I think. I follow Him into the entrance hall, where the others are collecting their coats and filing out into the skin-crisping afternoon overcast, then we walk through a corridor leading deep into the rabbit warren of Number 10. Eventually we come to the PM’s study. The curtains are drawn, for which I am grateful. There’s a small conference table at one end, but the PM heads straight towards a small cluster of chairs and a sofa that surround a coffee table. He waves me towards a seat but I bow my head. “You first, Majesty.”

Behind Him Iris briefly smiles approval. Her boss sinks into the armchair and nods at me. “Now will you sit?” He asks, and I hurry to comply. In public and in office He’s the Prime Minister, but Iris and I know better. He is a physical incarnation of the Black Pharaoh, N’yar Lat-Hotep, royalty that was ancient long before ancient Britons first covered themselves in woad and worshipped at Stonehenge. The Queen may still open Parliament, but she does so by His grace and indulgence. “I suppose you’re wondering why I invited you here,” He says, then grins like a skull that’s just uttered the world’s deadliest joke.

“Yes, Your Majesty.” I sit up straight, knees together, my hands folded in my lap. I briefly try to meet His gaze, but even though I am myself a thing that can soulgaze demons, it’s like staring at the sun—if the sun had gone supernova and turned into a black hole a billion years ago.

“I have a small problem,” He begins, then pauses expectantly.

Okay, here it comes. I tense, digging the points of my expensively capped incisors into my lower lip: “Is it something I can help with?” I ask, because there’s not really anything else you can say when a living god looks at you like that.

“Ye-es, I believe you might.” The gates of hell flash me a twinkle from what passes for His eyes. “Tell me, Baroness”—he already knows the answer to the question, He’s just toying with me—“have you ever visited the United States?”

* * *

Hello again, dear posthumous diary reader.

I know this is a lot to take in all at once, so for what it’s worth you have my apologies. But the CV I started with doesn’t give the correct context for my position under the New Management. I may no longer be Mhari Murphy, civil servant, from SOE Q-Division, but Dame Mhari Murphy, BSc (hons), MBA, FIC, DBE, styled Baroness Karnstein, and member of the House of Lords—but I am also, to use a technical term, utterly and unambiguously boned.

This is not my official work journal: I can afford to be honest here.

It used to be Best Practice in SOE for high-level personnel—line sorcerers and staff managers—to keep an up-to-date logbook so that in event of their incapacitation, retirement, or death in the line of duty their work would remain documented. In my experience, if you keep a written record of your wrongdoings you will only provide ammunition for your enemies, so I generally don’t do that. I have an orderly mind and I try to apply procedures humanely but exhaustively and keep within my remit. Work journals are for the experimentally inclined—hackers and the like—and my official work journal is mostly just a transcript of my weekly time sheets and performance appraisals.

Prior to CASE NIGHTMARE RED and the Leeds Incursion this was never an issue for me. I wasn’t engaged in active ops, and first I was too junior and then TPCF didn’t have the same requirement. (Dr. O’Brien doesn’t consider it useful to overdocument the antics of half-trained amateur superheroes.) Then everything went topsy-turvy and upside down while Continuity Operations were in effect, and keeping an up-to-date logbook was the least of my worries.

Since the installation of the New Management I’ve been stuck in experimental, improvisational mode. Nobody has ever chaired a House of Lords Select Committee on blood magic while working for a Risen God. And life, as they say, comes at you fast. Institutional knowledge retention is the name of the game, and it’s especially difficult when the institution is vulnerable to ideological purges. If you write something in an official logbook it may be used in evidence against you. But if you don’t leave any written record at all, and you die, then you leave your allies at a disadvantage.

Which is why I’m maintaining this secret diary.

And if you’re reading this and I’m not already dead, then may whatever gods you believe in have mercy on my soul, because the Prime Minister won’t.

* * *

Back when I worked with Mo and Ramona on the Transhuman Police Coordination Force executive, we made a habit of going out for a team-building exercise exactly once a week. Team building in this context meant drinking wine until we fell over. When you manage a rapid-reaction force you can’t afford to show any signs of stress in the workplace, because stressed-out management is contagious and degrades mission effectiveness. Hence the girls’ nights out in a non-workplace environment, with companions who had the security clearance to hear what I was moaning about. Not to mention enough alcohol to provide next-morning deniability if it all got too embarrassing.

I’m pretty sure those sessions saved Mo’s sanity, what with her violin gnawing on the corners of her mind. I don’t know what they did for Ramona, but she seemed to enjoy it, too. Me, I just needed the regular reminder that I was still officially human. But Ramona isn’t around any more—she got recalled, nobody seems to know what her people (BLUE HADES, the abyssal Deep Ones) make of the New Management—and Mo, Dr. O’Brien, is unavailable. Or maybe I’m just too much of a coward to talk to her since she … changed. As for family, my parents and kid sister aren’t cleared to know anything about my work (anyway, even if they were they’d be utterly useless), and I can’t vent at Fuckboy because reasons. Which means there’s only one person to turn to—and I know exactly how to bribe her.

“’Seph, darling, do you have anything planned for this evening, or are you free for—yes, absolutely! Listen, I need to pick your brain, so shall we make it my treat? I can sign you into the dining room at work and expense it if you meet me at the Cromwell Green visitor’s entrance at six—er, expect security screening? But you won’t believe the wine list! And all the latest gossip, of course!”

I hang up, then call the maître d’hôtel to reserve a table in the Peers’ Dining Room, because they tend to fill up fast on the evening before a debate. The chamber’s been uncommonly busy of late, processing a deluge of new legislation. The PM doesn’t really hold with new-fangled ideas like the Rights of Man (or Woman), let alone egalitarianism and democracy, but he works with what he’s got, and in this instance that means a House of Lords stuffed with life peers.

Most people think life peerages are handed out as retirement sinecures for front-rank politicians. But it’s also a means to recruit experts the government wants on tap to scrutinize bills in progress. Law professors, barristers, journalists, economists, historians: the sort of people who can’t be arsed going into politics as a career, but who are nevertheless deemed to have Useful Opinions to contribute to Parliament. That’s why there are so many life peers, and why they’re drawn from a surprisingly broad spectrum of British public life. The old aristocracy barely get a foot in the door any more. The only reason any of them are left is that the Lords Reform Bill got stitched up in a back-room deal in 2012, derailing the most recent attempt at fully modernizing the upper chamber.

Back when it was called the Invisible College, and “computer” was a job description for a working mathematician, the Laundry was funded out of the House of Lords black budget. It’s almost inevitable that these days we have people inside the House, supervising the muggles. But I still wake up some mornings wondering how I, a nice middle-class girl from Essex, got here, and how much longer I’ve got to make use of the perks of office before I’m found out.

On the dot of six o’clock I’m waiting in the lobby to meet Persephone Hazard as she comes throu

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...