- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

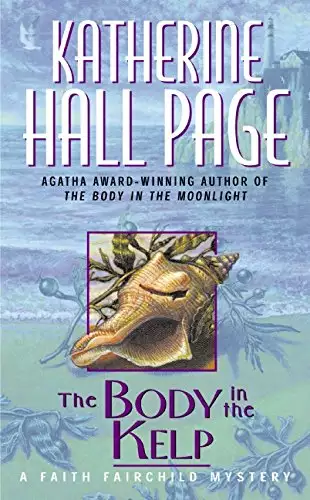

Synopsis

Faith Fairchild and her husband Tom, the handsome young minister, have left the little village of Aleford, Massachusetts, for a summer on Sanpere Island, off the coast of Maine. But Tom is called away to a three-week religious retreat in New Hampshire, leaving Faith to amuse herself and care for baby Benjamin, now safely into his terrible twos.

The summer begins innocently enough, with Faith involved in a seemingly harmless mystery, a hunt for treasure, the clues to which are cryptically embedded in a patchwork quilt. Then she and young Benjamin almost stumble over the body of another summer resident along the beach, and Faith is forced into more serious - and dangerous - detection.

©1991 Katherine Hall Page (P)2014 Dreamscape Media, LLC

Release date: May 29, 2001

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 212

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Body in the Kelp

Katherine Hall Page

1

Matilda Prescott was sitting up in bed piecing a quilt.

It was after midnight, but she wasn't sleepy. She never seemed to get really sleepy anymore and only tumbled in and out of fitful naps. Not what you'd call an honest-to-goodness night's sleep. Catnaps.

The cat, meanwhile, was snoring away at the foot of the pine four-poster that had been Matilda's grandmother's marriage bed. Matilda contemplated him with mingled affection and exasperation. Darn cat.

She put in the last stitches and cut the thread, then reached for a pencil from the nightstand. At the edge of the quilt top she lightly printed: "M.L.P." Matilda Louise Prescott. She'd always liked the way her name sounded. Solid. Then she added a few words. She'd embroider it in the morning.

The bedroom door opened a crack. Matilda glanced up briefly without surprise.

"Now what are you doing here at this hour? Oh, I know you're up and around. Don't think I don't know what's going on, but what do you have to come bothering me for? Just get out and leave me be. I'm sick to death of you. Sick to death of all of you."

The door closed. An hour later it noiselessly opened again. Matilda didn't look up. She thought she must be falling asleep, but this wasn't sleep. She needed some air. She gasped for breath. Too many covers. She seemed to be tangled up in the quilt, but when she tried to pull it off, it wouldn't budge.

Sick to death.

Faith Fairchild and her husband, Tom, were sitting on the porch of the small Maine coastal farmhouse they had rented on Sanpere Island for the month of August. Tom was reading and Faith was doing nothing. The house was set high upon a granite ridge, and a broad meadow swept down to a cove. Across the water was a lobster pound, and Faith had grown accustomed to the putt-putt-putt of the lobster boats delivering their catch. When the wind was right, or wrong, they could smell the bait and fuel for the boats, a powerful combination; but somehow it seemed to go with the territory.

The farmhouse had long since been converted to summer occupancy and was filled with all the appropriate paraphernalia a rusticator might need: croquet and badminton sets, picnic gear, rain hats, sun hats, star charts, jigsaw puzzles, fishing poles, butterfly nets, board games, and bookcases crammed with slightly musty copies of Wodehouse, Jack London, Mary Roberts Rinehart, E. Phillips Oppenheim, plus all the paperbacks the family had ever acquired as well as those left behind by tenants and guests, everything from Jackie Collins to May Sarton. The adjacent barn hadn't seen a cow in more than fifty years, and it too was filled to the rafters with equipment for leisure-time activities: bikes, a Ping-Pong table, canoes, a kayak, gardening tools. Faith found it daunting even to look in there and unconsciously stood a little straighter whenever she entered the door. All this clean living--plunges into the arctic water at dawn followed by cold showers, no doubt--left her feeling vaguely uneasy.As if Teddy Roosevelt's ruddy, hearty ghost was spying on her from behind one of the archery targets. Her plan for August had been something less strenuous in the Hamptons.

Tom, however, was delighted. This was exactly the way he and his family had spent their summers, and the rest of the year, on Massachusetts's South Shore. When the weather had been too bad for messing about with boats, rafts, or anything else that would float--and it had to be gale-force winds to discourage the little Fairchilds--they had holed up inside the house to play Monopoly for hours. Faith's idea of a good time as a child had been to stroll over to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and play hide-and-seek in the Egyptian wing, followed by hot chocolate at Rumpelmayer's. She loathed all board games, and the only card games she knew how to play were go fish and poker.

Still, she liked the farmhouse and her native curiosity--"dangerous curiosity" according to Tom--had prompted her to snoop around trying to piece together a picture of the Thorpe family who owned it but no longer used it.

There was a photograph album in the attic that affirmed her conviction that their shoulders were broad, calves sturdy, and haircuts terrible. They also seemed to have a penchant for wearing each other's clothes, or maybe they just bought them in lots. In any case, most of the garments were tan, and to say that L.L. Bean would have been haute couture describes them sufficiently. Nevertheless Faith had grown fond of the family and given them names she thought they would like--good Yankee names like Elizabeth, John, and Marian.

That Faith was here, five hours north of Boston, not two hours east of Manhattan, whiling away her time in this fashion, was due entirely to the blandishments of her neighbor and friend, Pix Miller, who had been coming to Sanpere since childhood. Pix painted such a vivid picture of deep-blue seas and murmuring pines that Faith agreed to try it. The fact that Pix also guaranteed a baby-sitter for two-year-old Benjamin Fairchild in the shape of her teenage daughter, Samantha, tipped the balance. At present Faith would have summered in Hoboken if someone hadoffered a baby-sitter along with it. They didn't call them "terrible twos" for nothing.

So, having made absolutely sure there was a bridge in good working order to the mainland, she packed her bug spray along with the Guerlain and prepared to "rough it." Pix was delighted. "You'll see. We'll have fun. There's always so much going on."

Staring at the absolutely calm water and flat horizon from the porch, Faith sincerely doubted that. Yet, although she wouldn't exactly say she was having fun, she was having something close to it. And Pix was right about one thing: Penobscot Bay was beautiful.

Plus there was the food--lobster, mussels, clams, fresh fish, and a small farmer's market on Saturdays with great vegetables and a goat cheese made by Mrs. Carlan that rivaled anything Zabar's stocked.

Faith's interest in food was personal and professional. She had risen to fame and fortune as the founder of a Manhattan catering firm, Have Faith, giving up the Big Apple for the bucolic orchards of New England when she fell head over heels in love with Tom Fairchild and married him soon afterward. Faith had a tendency to act precipitously. Tom, who was the village parson in Aleford, Massachusetts, did not. But this was a special case. A very special case.

Faith had managed to make life in the small town a bit more interesting by giving birth to Benjamin, finding a parishioner's corpse in Aleford's belfry, and getting locked in the killer's preserves cabinet--pretty much in that order.

Lately, when she was not chasing after Benjamin, conscientiously trying to help him reach his third birthday intact, she had been expanding the Have Faith product line--jams, jellies, chutneys, sauces. She was also thinking of starting up the catering business again in Boston, with the same name since Tom didn't seem to think it would rock the pews too much.

Faith was no stranger to the ministry. Her father and grandfather were both men of the cloth, and she had had an insider's view of parish life from childhood. The last thing she had everthought she would do was stretch her sojourn inside the goldfish bowl into adulthood. But in some cases the heart knows no reason.

Tom was naively insistent that it was possible to have a private life in a small parish and urged Faith to feel free to go her own way and voice her opinions. Although when Faith's remark to someone in the Stop and Save that she thought skinny-dipping was more wholesome than ogling the centerfold in Playboy came back to him as the minister's wife advocating mixed nude bathing, he was momentarily thrown.

At present, well out of the public eye, Tom was reading a Wodehouse and chuckling out loud. He was steadily working through all of them, and Faith had noticed some distinctly odd expressions in his speech lately, as well as an ever-so-faint British accent. She had become accustomed to his habit of sprinkling his conversation with his own versions of French expressions picked up in one blissful sophomore year in Paris, and it appeared these would soon be joined by those of France's hereditary enemies across the Channel. Faith both hoped and feared Tom was going to be eccentric in old age. They had both turned thirty in the spring, not thirtysomething, just plain thirty, and Faith was thinking a lot about age these days.

The wild roses that grew up over the porch filled the air with an intoxicating fragrance. A single gull flew across the sky, then dove straight in to the dark green water.

Faith had had enough scenery. She jumped up.

"What ho, Thomas, you old curmudgeon. How about a spot of footwook? It's absolutely ripping out and I must fetch the chip off the old escutcheon from Pix's abode."

Tom, deep in a fantasy of his own personal Jeeves, wrenched his attention away from the book and focused on his wife. She had cut her blond hair short for the summer, and it suited her. Some women have a tendency to look like fourteen-year-old boys when they do this, especially when dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt as Faith was; yet no one would ever mistake her for anything but what she was--a beautiful, sexy, healthy, and, at themoment, restless woman. He recognized the signs and abandoned his book with a tinge of regret. He was not above guilt induction.

"This is my only vacation, you know, Faith."

Tom was leaving Benjamin and Faith for three weeks while he went to work as one of the invited speakers at what Faith referred to as Spiritual Summer Camp. In fact, it was a series of retreats sponsored by the denomination. The Fairchilds had spent the long car trip from Boston thinking up workshop titles: "Job: Paranoid or Persecuted?"; "Muscular Christianity: Implants or Exercise?"; "Matthew and John: Who Really Told It Like It Was?" and so on. Tom would actually be speaking and leading discussions around the theme "When Good People Do Nothing," which covered everything from the plight of the homeless to the role of the church under Fascism. Faith thought it would be more interesting to speculate about good people doing bad things, but Tom pointed out it was often the same and this way he could fit in more topics. Since no forces on earth, or in heaven, would have dragged her to one of these noble gatherings, she felt she was not in a position to argue.

"Come on, Tom, don't tell me you won't have plenty of idle moments, and it's not as if a resort on a lake in New Hampshire is exactly a penal colony. Besides, you need the exercise. You're getting fat."

Tom hurled himself out of the wicker chair and grabbed Faith. "Take that back!" he cried, gently twisting her arm behind her back and trying to kiss her at the same time. "And if I am, which I'm not, it's your fault for cooking so well."

Having gotten him out of his chair, Faith went inside for a hat and some sun block. She had no intention of looking like tanned shoe leather by Labor Day.

"Shore or woods?" Tom asked, following her. You could reach the Millers' cottage either by a faint path through the pines or by scrambling over the rocks by the water.

"I don't care--which do you want?" Faith replied.

"Woods, my dear, every time." Tom smiled wickedly. Soon after they had been married, Faith had happily discovered Tom's love of the outdoors, or rather love in the outdoors. Freshair and/or open spaces were an instant aphrodisiac for him, and they had happened upon a soft carpet of moss about halfway to Pix's that was definitely beginning to show signs of wear. They started off hand in hand and Faith imagined they must look something like an overgrown Hansel and Gretel. Tom was in cutoffs, not lederhosen, but she quickly glanced behind her anyway for the bread crumbs as they left the brilliant sunshine for the cool shadows of the forest. The path was visible and there were no birds in sight.

Faith hadn't thought much about what Maine would look like, except she knew there would be a lot of water, rocks, and picturesque fishing villages. She was a city girl and proud of it.

Yet these ancient trees, draped in veils of gray moss and growing so close together they almost blotted out the sky, filled her with awe. So did the quiet. The pine needles cushioned their steps, and a twig cracking far away was all they heard, aside from an occasional rustle as some creature passed by. It was like a church. The time-honored simile, a cathedral. Maybe that was why Tom enjoyed making love here so much: Everything came together, so to speak. She decided to tell him this great insight, but not now--they had reached the carpet. "With my body I thee worship," she murmured.

Later, looking over at his peaceful face, eyes half closed gazing up at the dusty motes in the shafts of sunlight streaming down, she decided not to break the mood. What eventually did break it was insects--ants and the whine of a mosquito. That was the trouble with nature. It looked so good, but once you were out in. it, there were all these hidden drawbacks. It was so natural. Faith had never found that to be the case with Fifth Avenue for example, or Madison.

Tom slapped his arm. "Merde! These little buggers are eating me alive. Come on, Faith, let's get going."

They pulled on their clothes quickly and were soon approaching the cottage. Pix's family had been coming to the island for thousands of years and fortunately her husband, Sam, was a fervent convert. They had bought the land just after they got married, then built a small wooden summer house that sprawled outin several directions as various little Millers arrived. The oldest boy, Mark, was working as a sailing instructor farther up the coast, in a camp where ten-year-old Danny was currently a camper. Samantha, fifteen, preferred to stay on the island. Sam had taken off two weeks from his law practice in July and was returning at the end of the month.

Although the cottage was only about eighteen years old, it looked as if it had stood there for centuries. The clapboard was weathered gray, and Pix had planted delphinium, bleeding heart, phlox, and other old-fashioned flowers around the sides. There was a large vegetable garden in back and a substantial boathouse near the shore. This had recently been converted into a guest house, with a smaller shed nearby for Mark's sailboat and the dinghy the rest of them used to fish for mackerel, mostly in vain. Two potters, Roger Barnett and Eric Ashley, were currently renting the guest house, which the Millers still called the boathouse out of habit. Roger and Eric's own house, next to their studio and kiln, had burned down in May, and they had turned to Sam and Pix when they couldn't find a rental in the summer for love nor money.

As Tom and Faith approached, a giggling two-year-old traveling roughly at the speed of light zoomed around the corner, followed by two teenaged girls with outstretched arms, calling, "Benjamin! Stop!"

Faith could afford to look fondly on the scene. After all, she wasn't chasing him. His pudgy little legs were pumping away and his blond curls were plastered onto his forehead with the sweat of his exertion. He was laughing hysterically.

Samantha called out in explanation as she streaked past, "He thinks everything's a game!"

Faith and Tom nodded wisely, then went to find Pix.

She was in the kitchen making gin and tonics.

Tom gave her a big hug. "What a woman! You must be psychic. Even though I don't believe in all that, or at least not until Faith takes up table turning or Ouija boards."

Pix put everything on a tray and headed for the deck. Faith noticed that almost no one on the island ever stayed indoorswhen it was possible to be sitting out on a deck or in a field or on a rock. It probably had to do with the unpredictableness of the weather. It had been known to fog in for weeks on end, but Faith had a suspicion that Pix would go out anyway--in her sou'wester with a hot toddy.

Pix stretched out in an ancient canvas sling chair. That was another thing that made the house look old. It had been furnished with castoffs and permanent loans from Pix's relations, so everything looked as if it had been there forever. The wicker needed repainting and the Bar Harbor rockers new seats. All of which Pix and Sam planned to do as soon as they did everything else that needed doing. This was the only sure time of day to see Pix sitting. Usually she was picking berries, or making bread, or instructing the children in the flora and fauna of the area, or walking the dogs, or weeding the garden, or ...

She had started off life as a wee mite, and her whimsical parents had nicknamed her Pixie, which was abruptly shortened to Pix when she reached almost six feet at age fifteen. Faith had been trying to wean her away from the ubiquitous denim and khaki wraparound skirts and white blouses she favored, at least in the direction of Liz Claiborne and then who knows where? Today's outfit was one of the new ones, a bright blue-and-white-striped top with white shorts. Pix had fantastic legs, and heretofore Sam was probably the only one to know it. She stretched her long arms above her head and reached for the local paper from the table behind her chair.

"So who's having tea with whom this week?" Faith asked. She knew the first thing Pix read in The Island Crier was the social notes, "From The Crow's Nest."

Sanpere Island--the name was a corruption of the original French name bestowed by Champlain, St. Pierre--consisted of several towns, some of them no larger than a good-sized family. Each had a local correspondent who dutifully reported the news each week. Most of these ladies stuck straight to the facts. "The Weirs are at their cottage and entertained friends from Portsmouth, NH, over the weekend" and "Ruth Graham is out of the hospital and thanks all her friends for their cards and goodwishes." However, the correspondent from Granville, the largest town on the island, kept not only her ear to the ground but her eye on the horizon. She always started her section with a brief weather report from her end of the island, then mentioned what birds were around, animals she had noted in her yard, and what she was planting or harvesting, before getting to the more mundane activities of human beings.

"Well, let's see," said Pix, who had the paper sent to her in the winter so she wouldn't miss anything.

She approached the paper the same way she ate a boiled lobster, with meticulous dedication and an unvarying routine. First she'd suck out the sweet tender meat in the long thin legs most people threw away, then crack open the claws, and then the tail. Finally, she would open the body, spreading the tomalley inside on a saltine cracker and eating any roe before taking a pick to get every last morsel out of the cavity. Faith had never seen one person get so much meat from a lobster--or take so long to do it.

Settling down with The Crier on Friday when it came out, Pix had been known to make it last through Tuesday and once in a while longer if it was a special issue with a supplement--as for the Fourth of July, which increased the usual eight pages to ten. After "From the Crow's Nest" she turned, like most other people, to "Real Estate Transfers." The Fairchilds figured Pix could tell you the owner of every square foot of shore frontage and on back and how much the person had paid for it. At the moment the seller was usually the local Donald Trump, a man named Paul Edson, who had purchased land when it was relatively cheap in the Fifties and was now selling dear to the increasing number of Bostonians and New Yorkers willing to travel this far. Edson was an off-islander too. He'd married a local woman, a Hamilton, but that didn't change the way people felt about him, or now her. To say someone was "worse than Edson" on Sanpere was about as bad as you could get, not excluding mass murder, rape, and pillage. It was a rare day in town when he would return to his parked car and find air in all his tires. Although usually his wife sat guard, and nobody ever messed with Edith Edson.

"Come on, Pix, stop reading to yourself and share the goodies," Tom protested.

"I was just looking for Granville. Here she is:

"'Perfect weather this week. Lots of sunshine during the day and rain for the gardens at night. Three great blue heron were spotted in the cove near Weed's Hill and we can be sure that they are beginning to return to this part of the island. Tomatoes are so good, we can't put them up fast enough and have been giving them away, but the carrots have not amounted to much. Old seed? I don't want to point a finger, but the packet was pretty dusty. A very big turtle stopped traffic outside Alice Goodhue's house last week. Fortunately the fella didn't grab onto anyone's finger or toe! Come out some night and watch the Fish Hawks play at the Old High School. You won't see a better team and they are 4-0 in the county softball league.' Oh, terrific!"

"What is it?" Faith asked. From the tone of Pix's voice, it was not old carrot seeds or the Fish Hawks' winning streak.

"There's a Baked Bean and Casserole Supper at the Odd Fellows Hall next Tuesday night. Too bad you'll miss it, Tom," she said with real regret in her voice. "I know you'd love it."

Faith rightly assumed that Pix intended her to attend--and what was worse, eat. The baked beans might be okay, but she knew what a casserole was--string beans (probably not from the garden, those had already been canned for next winter), mixed with cream of mushroom soup, water chestnuts if the chef was adventurous and had been to the big supermarket off island in Bangor lately, topped with canned onion rings for crunch.

"The desserts alone are worth the price of admission. Now, Faith"--Pix leveled an admonitory glance at her--"don't turn up your pretty little gourmet nose. These ladies know how to cook."

Could the woman who sometimes served her family Kraft macaroni and cheese dinners and Dinty Moore stew be right? Faith doubted it, but she'd go. Blueberries were ripe, and that meant pie or maybe shortcake, the real kind of shortcake, on a biscuit, not store-bought sponge. New England was pretty reliable in theshortcake and other baked goods department, she had discovered. She cheered up about the dinner. Maybe there was a diamond in the rough out there who would do something delectable with lobster. Pix had given her a recipe for fiddlehead ferns clipped from The Crier last spring that had been delicious. Perhaps she was getting too critical. The thought was vetoed as quickly as it had come. The evening had tuna noodle written all over it.

"So what else is new?" If you had told her a week ago that she would be listening with not just pleasure but interest to a local gossip column, she would have shaken what was left of her locks in disbelief. Yet it was true. "And don't forget 'The Fisheries Log'--I want to know what those poor fishermen are getting compared to what Sonny Prescott is charging."

Pix continued, "Let's see, babies, birthdays, and family reunions. Gracious! Someone came all the way from Newfoundland for the Sanford gathering last weekend. They had a clam bake in Little Harbor. Oh, here's the card of thanks from Matilda Prescott's relatives: 'We would like to thank everyone for their kindness in this time of our bereavement.' I guess they couldn't really put in what they thought, namely: 'She was a cranky old lady, it was about time, and now we can finally get the house.'"

"What do you mean, Pix? Who was she? Any relation to Sonny?" Tom was as interested in gossip as Faith, though a fraction of a hair slower to admit it.

"All the Prescotts in the universe and especially on this island are related. Matilda was his aunt, or great-aunt. The house they all want is that beautiful Victorian in Sanpere Village you can see from the causeway. The question on everybody's mind is which one of the thirty thousand Prescotts will inherit. Matilda never married, so there are no children. The way I always heard it was she went away to the normal school, and when she got back all her brothers and sisters were married, so she had to stay at home and take care of her parents. And they lived a long time. When her father died, he was the oldest resident on the island and had the Boston Post gold-headed cane. But she did teach, in the old schoolhouse by the crossroads, and I guess she didn't spare the rod much."

Faith had stopped listening after "beautiful Victorian."

"You mean the house with the gazebo?!" she exclaimed. A lifelong apartment dweller with an instinctive distrust of only two or three stories, she had been surprised to discover that she occasionally fell instantly in love with a certain house--a butter-yellow rambling Colonial in Aleford, a Bauhaus gem in nearby Lincoln; houses that seemed to be as rooted in the setting as the trees and bushes surrounding them. She'd seen the Prescott house the first morning they'd arrived when she'd gone to the IGA for supplies. A causeway separated a large mill pond from the small harbor, and the house was set back in the woods across from the old mill with a spit of land projecting into the pond. The gazebo was at the tip of it, surrounded by slender white birches like girls in their summer dresses. The house, keeping watch a discreet distance away, was tall and stately, with the gingerbread, gables, and furbelows of the period kept firmly in check. Both the house and gazebo looked squarely out toward the western part of Penobscot Bay. Sunsets could be spectacular, streaks of deep rose and violet stretching across the sky, randomly broken by the dark shapes of islands that pushed up into the horizon line--islands with names like Crabapple, Little Hogg (and Big Hogg, which was smaller now), and Ragged Top.

"Yes, that's it." Faith was dazed for a moment by the sound of Pix's voice. She had been mentally dressed in voile and a picture hat, sipping some chilled chablis with Tom as they gazed at the setting sun and each other. Invisible hands were meanwhile feeding and putting her suddenly docile child to bed.

"That's one of the most beautiful houses I've ever seen." Faith spoke enviously. "I don't suppose you have any Prescott blood mixed up with all those New England strains, Tom?"

"Sorry to disappoint you, love, and I agree. It is a jewel. I wonder why houses like that never seem to end up as parsonages." He sounded a bit wistful. "Probably whoever inherits it will make it into condominiums or something."

Pix answered, "Oh, I doubt it. That's only farther down the coast so far. I think anyone who tried to introduce the idea of condominiums here would get quite a cold shoulder. Or worse.I'm not sure everyone here even understands what they are, but they sound bad--like Yuppies, and years ago Hippiea."

"Which reminds me," said Tom, "I saw a flower child on the clam flats yesterday morning, quite early. Youngish with all the accoutrements--long hair, bandanna, granny sunglasses, tie-dyed mini dress around three inches long. And she had a baby or something in a pouch strapped to her back. Was I dreaming or is she a neighbor?"

"I saw her too, Tom, later. She was coming over the rocks, spied me, and fled instantly--before I had a chance to say anything."

"That's Bird, not her real name," Pix replied. "Although come to think of it there must be quite a few adults with similar names bequeathed to them by their letting-it-all-hang-out parents--I actually knew someone who named her daughter Emma Goldman Moonflower. Anyway, Bird lives with her significant other in that tiny shack you can see from your beach, directly across the water from the lobster pound. I don't think it even has indoor plumbing. They're into macrobiotics and she was probably gathering seaweed. The guy she lives with, Andy, is a rock musician and seems to spend most of his time in Camden playing with a group down there. I don't really know them, although they've been here all winter and I can't imagine how they survived in that house, especially with a baby." Pix paused for breath. There was nothing like fresh Maine air and a gin and tonic to loosen her tongue.

"Someone you don't know? Well, I, for one, am shocked," teased Tom. "You're slipping, Pix."

Pix clamped her mouth shut and returned to the paper.

"Come on, make up and read me 'Police Brief,' you know it's my favorite. What kind of a week has crime had on the island?" Tom cajoled. With only one officer of the law and accordingly one police car, he hoped it hadn't been too unruly.

Pix acquiesced readily. "Well, the kids are stealing hubcaps again. Oh, and this is really funny--I'll read it: 'A pickup truck was found upside down in Lover's Lane last Tuesday evening. A search found a quantity of empty beer cans inside, but no driver.The truck, a 1967 Ford, was registered to Velma Hamilton, who reported it stolen the next day. The truck was totaled and the matter is under investigation.'"

Tom and Faith laughed. "You mean there really is a Lover's Lane on the island?" asked Tom.

"Yes, you follow Route 17 to Sanpere Village and it's the road before the lily pond. But what could they have been doing to turn the truck upside down?"

Tom and Faith laughed harder. Faith caught her breath and said, "Oh Pix, only you. Don't you think the truck just drove off the road? It couldn't have been stopped and flipped over no matter how frisky the couple were."

"You never know; one time I heard--" Pix started, when she was unfortunately interrupted by the appearance of a much-disheveled Samantha lugging a squirming Benjamin. She came up the stairs to the deck and deposited him on Faith's lap before he could take flight again.

"I hope it's all right, Mrs. Fairchild, but Arlene and I want to go swimming now while the tide is right." She motioned behind her. "Arlene, this is Mrs. Fairchil

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...