- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

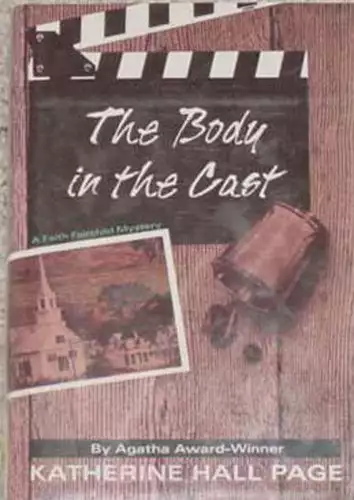

The Body in the Cast, the fifth volume in Katherine Hall Page's cozy mystery series featuring amateur sleuth Faith Fairchild

Hollywood has come to town — and Faith Fairchild has to feed it! Hired to cater meals for the movie crew that is filming a modern-day version of The Scarlet Letter in the tiny New England village of Aleford, Faith is eager to treat the talented tantrum-throwers to the best of her culinary delights. But an accusation that her famous Black Bean Soup is poison has left a bad taste in Faith's mouth. Her exploration into the source of the nasty slander leads the amateur investigator behind the scenes to a shocking off-camera murder. And suddenly more than Faith's reputation is at stake — her life itself could end up on the cutting room floor.

Release date: October 15, 1993

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 276

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Body in the Cast

Katherine Hall Page

Chapter One

The page of life that was spread out before me seemed dull and commonplace, only because I had not fathomed its deeper import.

Aleford, Massachusetts, was reeling--literally. Not only was an actual Hollywood movie crew in town filming a modern version of The Scarlet Letter but Walter Wetherell had abruptly resigned from the Board of Selectmen, igniting a fierce three-way contest for the vacant seat.

And, as if these were not enough, Town Meeting was in session, with all its attendant intrigue: loyalties and grudges handed down from one generation to the next; back-room political maneuvers; and immediate front-room protests. Never before had the dismally bleak month of March seemed so bright. March--when the possibility of a crisp white snowfall was greeted with about as much enthusiasm as another tax increase from Beacon Hill. March--when only the young, or perennially foolish, talked about smelling spring in the air and the imminent arrival of daffodils. March--whether accompanied by lions or lambs, a month to get through.

Over at the First Parish parsonage, the Reverend Thomas Fairchild and his wife, Faith, were adapting themselves to thenewest member of their family, Amy Elisabeth. It had been Baby Girl Fairchild for about twenty-four hours following her birth the previous September as Tom and Faith battled it out, albeit with velvet gloves. Faith had counted on a dramatic pose in the hospital bed, fresh from her labor, to win the day. It didn't. She was forced to give in on Sophie, with all its sweet little French schoolgirl connotations, but rallied to demand that Tom abandon Marian, after his mother. A nice woman, to be sure, yet what would Faith's own mother, Jane, have to say? The remote and absurd possibility that Faith might be forced to have another baby to keep both grandmothers happy had presented a singularly grueling specter at the moment. For a while, it appeared agreement might be reached on Victoria, or Victoire (Faith persisted), but both parents eventually concurred that it might not be clear whose victory and over what, since it wasn't even clear to Tom and Faith themselves. Faith's escape from a crazed kidnapper in a French farmhouse during the fourth month of pregnancy? Or, Faith's suggestion, the whole less than enjoyable experience of childbirth itself? A memory any number of friends had assured her grew dim with time. And this had proved to be the case--somewhat. Ben's birth three and a half years earlier had receded to a far distant shore, then instantly crashed forward into total recall the moment her water broke.

They had finally settled on Amy, but Faith perversely decided to hold out for the French spelling, Aimée, to almost a bitter end. It was only when Tom sang "Once in Love with Amy" for the hundredth time, firmly declaring Ray Bolger wasn't immortalizing an Aimée, that Faith gave in. She pulled her last punch and salvaged the European s instead of z in Elisabeth, and the family turned to more important things like nibbling the baby's toes and wondering how fingernails could be so tiny.

Faith Sibley Fairchild had not always lived in Aleford, a fact she no longer blurted out insistently when introduced but that she nevertheless managed to subtly work into the conversation--suchwas the increasing wisdom that age, and life in a small village, conferred. She had grown up in Manhattan, established herself as one of the hottest caterers in town as an adult, and reluctantly left after she realized the sole way she could have her cake and eat it was to move north, marry Tom, and make sure she had a decent stove.

The institution of the ministry was not foreign to her. Both her father and grandfather were men of the cloth. It was this familiarity with parish life during her formative years that made her swear an oath with her sister, Hope, one year younger. Neither would marry men working for any "higher authority" than someone with a name on the door and a Bigelow on the floor. The girls went so far as to avoid dates with Matthews, Marks, Lukes, and Johns for a time, until this became counterproductive when Hope fell for a particularly attractive bond salesman named Luke at work. Still, she married a Quentin, an MBA, not an MDiv, and lived up to her side of the bargain. It was Faith who fell from grace when she met Tom, sans dog collar, at a wedding she was catering, not realizing he had performed the ceremony until it was too late.

Almost five years had passed. Faith had become a bit more used to Aleford and Aleford to Faith. However, she still suffered frequent longings for the sound of taxi horns blaring, the sight of blue-and-yellow Sabrett's umbrellas protecting spicy dogs and kraut, and the aroma of Bergdorf's fragrance counters. You could take the girl out of the city, but you couldn't take the city out of the girl. Her stylish New York clothes and penchant for Woody Allen movies were no longer hot topics for the early coffee and muffin crowd at the Minuteman Café. If she was talked about, and she was, the conversation now tended toward her knack for both finding corpses and subsequently solving the crimes.

But old habits die hard in places like Aleford, and stalwarts like Millicent Revere McKinley, a descendant of a distant cousin of Paul Revere and the pillar of the DAR, Aleford Historical Society, and WCTU, regarded Faith's sleuthingabilities as child's play compared with Millicent's own encyclopedic knowledge of the life and crimes of every Aleford inhabitant for the last fifty years. This knowledge was gleaned in a variety of ways, the predominant being her daily hawk-eyed observations from a perch in the front bay window of ye olde ancestral Colonial house, happily located directly across from the village green and with a clear view down Battle Road, Aleford's main street. No, Miss McKinley, thank you, was not interested in Faith's supposed abilities pertaining either to detection or cuisine. Millicent clung to her initial impression; to do otherwise would have suggested uncertainty, or worse--whimsicality--and she chose to dwell on the peccadilloes of a person from "away." Her attitude was made manifest by audible sighs, especially where two or three were gathered, followed by the words "Poor Reverend Fairchild."

When Faith reopened her catering business, Have Faith, after Christmas in the former home of Yankee Doodle Kitchens, Millicent added, "And her poor neglected little children" to the litany, smiling a gentle, mournful smile before moving on to the next audience.

"Honestly, Tom, I should be used to her after all this time, but she still gets under my skin," Faith exploded one evening after the neglected children had been read to, cuddled, and generally spoiled rotten before drifting off to sleep. "It's a Gordian knot and I'm all thumbs. If I hadn't started the business again and had stayed home all day with Amy, dear as she is, I'd be a crazy woman by now. Or let's say crazier. On the other hand, working makes me feel guilty about leaving her, even for short periods. And I know the house is suffering."

"I'd rather have you sane--or are we saying saner? Besides, you've done everything you can to be with Ben and Amy as much as possible." Tom looked around the living room from the depths of the large down-cushioned sofa, a comfy legacy bequeathed by one of his predecessors. "The house looks fine--and so, Mrs. Fairchild, do you." Faith was conveniently near and he drew her into his arms.

"I suppose you're right," she said contentedly. "Anyway, the flowers help." Faith had placed pots of bright tulips and freesia she'd forced, so as to distract the eye from whatever might be out of place or in need of cleaning. It was a trick she had learned from her Aunt Chat: "Put plenty of flowers around, keep the silver shiny, and no one will ever know how many dust bunnies are under your bed."

While letting some of the housework slide, although she was managing to keep the bunnies from reproducing at too rapid a rate, Faith did everything guilt-ridden moms everywhere do to minimize the time away from the kids. She may even have gone overboard, she'd thought on more than one occasion, longing for a moment alone. It was getting hard to remember the last time she'd had a shower more than three minutes long, and a soak in a perfumed tub seemed like a chapter from somebody else's life.

Yankee Doodle's premises had needed some remodeling, so Faith had had a carpeted play area installed at one end of the huge space, complete with Jolly Jumper, playpen, shelves for toys, and a small table and chairs. Most days, the baby came to work with her. Just as the books said, second child Amy Elisabeth was easier, settling placidly into two long naps and food at reasonable hours, except for that very early morning demand for mother's milk--now! Ben was at nursery school through lunch and spent the afternoon with Faith or, when she was pressed, in day care with Arlene Maclean, mother of Ben's beloved friend, Lizzie. Arlene also took Amy at times. Arlene didn't smoke, wasn't noticeably psychotic, and, if Lizzie was proof, knew what was what in the Raising Nice, Obedient, Yet Interesting Children department--a department Faith still felt much less familiar with than, say, Better Dresses at Bloomie's.

It had been an enormous amount of work starting the business in the new locale, far from her former suppliers and staff. She'd been discouraged almost to the point of giving up when Niki Constantine, a young Johnson and Wales graduate fresh from washing pots at Biba's, one of Boston's culinary shrines,strode confidently in to be interviewed for the job of Faith's assistant. Niki had grown up in nearby Watertown. Her parents still operated a bakery there. She nibbled all day, tasting constantly, and never seemed to put an ounce on her wiry frame. Her tight, short black curls had a few streaks of premature gray and she brought an air of serious professionalism to the job that matched Faith's own.

They soon became a team: two ambitious, hardworking women who were often convulsed in laughter, as when Niki presented Faith with a tray of spectacularly fallen individual soufflés Grand Marnier, declaiming in solemn tones, "They just couldn't keep it up." Niki also tended to answer "Food is my life" in a deceptive deadpan to most queries.

So, all was well, or at least this is what Faith optimistically told Tom, and herself, whenever she returned home at the end of a particularly long day. Amy was benefiting from having a contented mom, not to mention the purees of artichoke hearts and spoonfuls of pâté de foie de volaille avec champignons the baby gobbled down with significantly greater gusto than she brought to Gerber's fare. Ben was the same, munching chocolate madeleines and milk as his after-school snack. And there were stretches when Faith wasn't working much at all and packed the kids up for enriching trips into town or dragged them along on much-neglected parish calls. She was, after all, a minister's wife. And she knew her duties.

The first inkling that movie people were coming to Aleford had been in December, shortly before Christmas, when a tall, thin young man in an olive Joseph Abboud suit and slightly darker topcoat had showed up at Battle Green Realty and asked the startled owner, Louisa May Talcott (her mother had read Little Women over seventy times), whether she could show him some houses. December was a slow month and Louisa May had been engrossed in the latest Charlotte MacLeod mystery when the sleigh bells on the door jangled. She'd looked up, to find her own distorted reflection in the sunglasses her caller had donnedagainst the novel glare of white snow. Politely removing his shades, he explained he wanted to rent a small Cape Cod house, authentic if possible, located on several acres, preferably with lots of trees. It was the work of a moment to drive him out to the Pingree place, a two-hundred-year-old Cape. It had the requisite light-obscuring windows, low ceilings, and small, drafty rooms. The house also abutted a large stretch of conservation land complete with forest, streams, a bog, and several picturesque tumbled-down stone walls. Delighted with the house and its setting, the stranger revealed he was Alan Morris, the assistant director on a new Maxwell Reed movie. Alan shot countless rolls of film, took copious notes, and left a check that turned the visions of sugarplums dancing in Louisa May's head into more palpable goodies under the tree: a laptop computer for husband, Arnold; Nintendo for little Toby; and the cashmere twin set from Talbots she'd long desired for herself.

The Pingrees went to Paris.

The advent of the movie people had occupied center stage throughout December and into February. Aleford dubbed itself L.A. East as it watched the progression of various individuals arrive to scout locations, arrange permits, rent a house for the director, who did not like hotels, and book blocks of rooms for everyone else at a Marriott in nearby Burlington--Aleford itself had but one hostelry, which boasted only three bedrooms. (You did get a mighty delicious breakfast thrown in.) Everything had to be in place well before the March shooting date. But all this, even the helicopter flying low over the conservation land, was firmly relegated to the wings once the news of Walter Wetherell's resignation got out.

While some residents of Aleford had been known to take an interest in national and state politics, particularly during presidential and gubernatorial years, it was local elections that gripped the hearts and minds of the majority. Balloons did not tumble down from the ceiling, nor did smiling, well-groomed red-white-and-blue-clad families grace a podium when candidacieswere declared. But this did not mean there wasn't plenty of hoopla. It merely took a different form. Perhaps a small, discreet notice in the town paper, the Aleford Chronicle, or, better still, a letter to the editor, which didn't cost anything. Then as things heated up, there would be larger ads listing the names of those who endorsed the candidate. Properly studied--and there were few Alefordians who were not adept at the art--the names revealed more about the candidates than any debate or position paper. Once the ads appeared and everyone had figured out who was representing whom, bolder measures would be taken. The tops of cars sprouted signs precariously anchored by bungee cords and the space between front and storm doors filled up with fliers describing the candidates' records all the way back to things like "Winner of the Fifth Grade All-Aleford Spelling Bee."

Campaign mores were as invariable as the flag raising every morning on the green.

In the late fifties, someone had passed out ballpoints with his name emblazoned in gold ink on each and every one, but the general opinion was that he'd gone a little too far--for which he was resoundingly defeated. In a gesture of defiance, or remorse, he moved closer to Boston, where his flamboyant style presumably found a more congenial home.

The first fireworks in the current election had started in February, before any of the candidates were announced.

"Why in tarnation Walter Wetherell thinks he has to resign just because he's having some sort of pig valve put in his heart is beyond me," police chief Charley MacIsaac told Faith one particularly chilly day. He'd formed the habit of dropping in at the caterers now and then for a cup of coffee, and Faith was glad to have him. She missed their morning colloquies at the Minuteman Café. She'd been afraid she'd get woefully out of touch when she went back to work, until Charley had solved the problem. Not that he was a chatterbox, but she could usually work the conversation around to what she wanted to know. She didn't even have to try this time. Charley was more than ready to spill his guts.

"I didn't know you were such an ardent supporter of Walter's. I thought you two were at odds over widening Battle Road," Faith commented.

"We are, were, whatever. Somebody's going to get killed on that road. It cuts straight through to Route 2A and if he had gone there at rush hour like I asked, he'd have seen what I was talking about. All his talk about preserving the quality of the community--it's really because it so happens his cousin lives over there. More like preserving the quality of Bob Wetherell's front yard," Charley fumed.

"Then I would have thought you'd be happy Walter is resigning. You might get someone who agrees with you."

"And I might get somebody who doesn't. But I will get somebody I don't know, or maybe do know, which could be worse. And what's sure is, whoever it is, it will be someone who'll be asking a million dumb questions--and the meetings are long enough as they are. No, in this case, I say take the devil you've learned to put up with."

"You just don't like change, Charley. Besides, the poor man can't be expected to perform a selectman's duties while he's recuperating from major heart surgery."

"People pamper themselves too much these days. If there's anyone to feel sorry for in all this, it's the poor damned pig."

Chief MacIsaac was echoing the opinion of most of the town, and for a while Winifred Wetherell did her shopping in Waltham at the Star Market instead of the Shop'n Save. And rather than going to the town library, Walter read all the books he had at home that he'd been meaning to read but didn't actually want to.

The identity of the first candidate to file remained a secret for only the five minutes it took town clerk Lucy Barnes to lock up the office and walk briskly down the street to the Minuteman Café. It had been a slow week for Faith and she was actually present at the historic event. She was sharing a table with Pix Miller, her close friend and next-door neighbor, and Amy, the latter delightedly finger-painting with corn muffin crumbs and spit while securely strapped into her Sassy seat.

"There I was, not expecting a thing, when I saw a shadow at the door," related Lucy breathlessly.

Faith knew the door well. She'd copied the list painted on its frosted glass and sent it to her sister, Hope, upon arriving in Aleford as a new bride. Under TOWN CLERK'S OFFICE in impressive bold script, it read: DOG LICENSES, MARRIAGE INTENTIONS, BIRTH CERTIFICATES, DEATH CERTIFICATES, VOTER REGISTRATION, ELECTION INFORMATION, ANNUAL CENSUS, BUSINESS CERTIFICATION, RAFFLES, FISH AND GAME LICENSES, MISCELLANEOUS. It was the last item that had caused Faith the most amusement. What could be left? she wondered.

The town clerk had the attention of the entire café.

"Before I had a chance to even think who it might be, the door bangs open and it's ..." Lucy paused; it was her moment. "Alden Spaulding. 'I'm going to be your new selectman,' he says, bold as brass, as usual. 'Give me the papers.' I hadn't expected a please or thank you, and it's a good thing I didn't. Anyway, what are we going to do?"

It was a call to arms.

Alden Spaulding had few friends but some grudging admirers, whose comments took the form of, "Whatever else you may say about Alden, you have to admit the man knows what he's about"--local parlance for "knows how to make a buck." While in his twenties, forty years before, Alden had taken his inheritance and put it all into what was then the novel idea of a duplicating service. Over the years, he had expanded his offerings and locations, becoming one of the wealthiest men in the area. He was the proverbial bridegroom of his work, remaining unencumbered by a wife and family; swooping in without prior notice at one of his branches to see what the laggards were not doing at any time of day or night.

Politically, he was a rabid conservative, so far right as to be out in left field. This would not have been a problem in other election years, but it posed a major difficulty this time around. Aleford's Board of Selectmen was composed of five citizens. Since anyone could remember, putting said recollection somewhereshortly after the Flood, there had always been two liberals, two moderates, and a conservative on the board. Walter Wetherell had been one of the moderates, the swing votes. With two conservatives, the historic balance of power would be altered and, what was worse, would put all the town's major decisions in the hands of the remaining, tie-breaking moderate, Beatrice Hoffman, who could never quite seem to make up her mind.

Chief MacIsaac groaned audibly. If Spaulding was elected, the new cruiser he hoped to get the town to buy as a replacement for the barely operable 1978 Plymouth Gran Fury currently doing duty would be a 1995 or 1996 by the time Bea made up her mind, because of course the vote would be two to two. He could hear her now: "We mustn't be hasty. This decision is too important to be made in a cavalier fashion." Cavalier. Many's the interminable meeting he'd wished someone, dashing or not, would ride in on a big black horse and carry Bea off. That was another thing. They would be meeting continuously, since one session would be ending as the next was called to order. Why the police chief had to be at these things was beyond him, but the forefathers had decided, maybe two hundred years ago, that the law had to be present, and no one was about to change it now.

"Obviously someone has to run against him--and soon. We can't let him remain unopposed." Faith spoke firmly, confident in the knowledge that no one expected her to run--not because as a wife, mother, and businesswoman she obviously didn't have a free moment to work the crowds, but because she had not lived in town the requisite thirty or so years and/or was the product of several generations of Alefordians.

Her stirring words, however, did not have a galvanizing effect on the group in the café. Everyone assumed a studied lack of activity and even nonchalance as they looked out the window, toward the ceiling, anywhere save in the direction of Faith's eye.

"Well, perhaps no one here"--the room relaxed and peopledared to sip their coffee once more--"but we have to make an effort to find someone. Any ideas?"

Pix would normally have felt compelled to volunteer, except for the fact that her husband, Sam, had declared heatedly that if she took on one more thing, he was going to incorporate himself and the children as a charity and make her head of the board of directors to force her to stay home at least one night during the week. She did have an idea of someone else, though.

"What about Penelope Bartlett? She's never been on the board, and I can't imagine why not."

"Perfect," cried Lucy Barnes in delight. "No one is more dedicated to Aleford than Penny, and she has so much good common sense. I'm sure she'd do a fine job."

"Perfect," declared Chief MacIsaac, in what Faith would have sworn was a parody, were he given to such things. "Alden will be running against his half sister, someone who hasn't spoken to him in twenty years or so. Should be fun."

"I didn't know Penny Bartlett was Alden Spaulding's half sister," Faith said to Tom that evening as he got ready to leave the house for a session of Town Meeting. He'd been an elected Town Meeting member since he'd arrived at First Parish. He thought it would be a good way to get to know Aleford and its inhabitants. Besides, Fairchilds always sat at their local Town Meetings, guarding their seats and passing them down as lovingly as they did their season's tickets to Celtics games at Boston Garden.

"You really should ask someone else for the details, but I think Alden's mother died when he was about seven or eight and his father married Penny's mother, who was much younger and a neighbor, in rather indecent haste."

"Probably needed someone to cook and do the wash," Faith said.

"I don't think so. He was comfortable, as we New Englanders like to say, and could have hired any number of housekeepers."

"'Comfortable,' which means something akin to rich as Croesus. No, he wouldn't need to cut costs. Maybe he wanted a mother for little Alden. Then again, given the evidence of their offspring, it's probable that the first Mrs. Spaulding wasn't up for the title of Mrs. Congeniality and he may simply have wanted a pleasant spouse."

"Possibly. Penny's mother, his second wife, died long before I came here, but there are plenty of parishioners who remember her, and I've always heard her mentioned with great affection. No one mentions Alden's mother. Since Alden's father was active in the congregation and Alden, too, in his own inimitable way, I'd imagine she must have attended, although perhaps she was an invalid of some sort."

Faith thought they ought to get off the subject of the Bartletts. Alden's participation in the congregation, along with a decent-sized pledge, took the less welcome form of line-by-line sermon critiques and objections to the amount of money spent on social concerns. He seemed to regard his tithe as an entitlement.

"What's on the agenda tonight?" she asked. Faith had no desire to attend Town Meeting, yet she liked to know what was going on. It made the old Tammany Hall look like a Brownie Scout troop.

"The library budget. I could be late, very late. Our friend Alden, who is maintaining a very high pre-election profile these days, has submitted an alternate resolution calling for drastic cuts in staff and hours. He wants the library closed weekends and Wednesdays. The rationale for this being that people read too much and should be out getting some exercise instead, which costs the town nothing. Oh, and he wants to eliminate the library aides and have patrons reshelve their own books when they return them."

"I know we have to cut, but this is ridiculous. Surely no one will vote with him."

"I wish I could be certain. There's a strong feeling in town that spending is out of control, and a sizable contingent seesAlden first and foremost as a successful business manager. These are the people who will vote with--and for--him. Enough philosophizing. We need someone who knows dollars and cents-type stuff. We do have to cut the budget, but not with a machete."

"Have fun. I don't envy you." Faith kissed her husband and sent him off with his shield. She only hoped he would not come home on it.

Aleford had resolutely resisted the blandishments of the local cable television franchise. No one could see the point of paying perfectly good money for extra television channels when they already had more than they wanted to watch. Yet when the company offered to broadcast Town Meeting on its local access station, quite a few heads were turned. No more sitting in the hard seats up in the balcony of the Town Hall, straining to hear what the members below were debating. No more listening to embarrassing stomach rumbles, as no food was allowed in the hall. The cable TV proposal had come up at last year's Town Meeting and lost by a whisker. But with the added incentive of the election--the company had promised to film candidate's forums and live ballot counting--it was sure to pass this time, unless Millicent McKinley could rally a few more Town Meeting members to her camp. The cable proposal, she declared, was one more example of the moral turpitude rapidly creeping into all aspects of everyday life. It was positively indecent to think of such a hallowed tradition as Town Meeting being broadcast to people who might be doing Lord knows what as they watched. She had heard of homes where a television was actually in the bedroom! If someone wanted to know what was going on at Town Meeting, he or she could go to Town Hall just like all the elected members. It was a question of simple equilibrium, she stated. Though people weren't too clear what she meant by the phrase, it sounded good and they didn't doubt her sincerity.

Faith had waited up for Tom and he was late. She'd been reading M. F. K. Fisher's The Gastronomical Me in bed and gotup to get him something to eat when she heard the car pull into the driveway. She'd been stunned when she first learned that they had to sit all those hours without any form of nourishment. "An awful lot of people chew gum," Tom had told her. "Sometimes I look around and feel like I've been put out to pasture with a herd of malcontented cows."

"I'm almost, but not quite, too tired to eat," he said, collapsing at the kitchen table in anticipation.

Faith was mixing beaten eggs, chopped green onion, crisp, smoky bacon, and Parmesan cheese into some spaghetti she'd cooked earlier and set aside. She poured the mixture into a frying pan with some hot olive oil and spread it out to form a large, flat mass. "Did Alden's amendment win?"

"Praise the Lord, no, but he got more votes than I would have expected. I think I'll pay a call on Penelope tomorrow and add my voice to the swelling chorus urging her to run. She looked slightly confused and blushed a couple of times when people passing her to go to the john or whatever leaned down to whisper in her ear. I'd say the campaign to get our Penny to throw her bonnet into the ring is on with a vengeance."

"Nice to know you're not getting too involved in all this, darling." Faith smiled at him as she deftly slid the golden brown frittata onto a plate and flipped it back into the pan to cook on the other side.

Two days later, Penelope Bartlett entered the race, which came as no surprise. The surprise was James Heuneman's appearance at the town clerk's office and his demand for nomination papers the same afternoon.

This time, it was Millicent who carried the news. Faith was beginning to think she should put some tables and chairs in her catering kitchen, since so many people seemed to regard it as an outpost of the Minuteman Café. Millicent was ostensibly there to get Faith to sign up to work on Penny Bartlett's campaign.

"A spoiler, plain and simple. James Heuneman knew that Penny intended to run!" Millicent bit down vicio

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...