- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

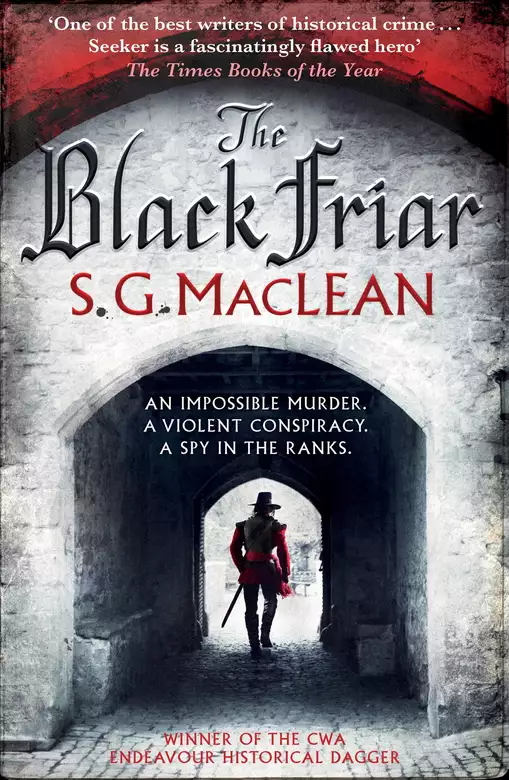

Synopsis

London, 1655: Damian Seeker, Captain of Cromwell's Guard, is all too aware of the danger facing Cromwell. When a stonemason uncovers a body dressed in the robes of a Dominican friar bricked up in a wall, ill-informed rumours circulate. Seeker, who instantly recognises the dead man, must discover why he met such a hideous end. Unravelling these mysteries is made still harder by the activities of individuals who are not what they seem.

Release date: October 6, 2016

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Black Friar

S.G. MacLean

Goodwill Crowe straightened himself, brushed grit and stray rushes from the front of his jerkin and his hose. Nathaniel was too frightened, Patience too astonished to say anything. Only Goodwill’s wife, Elizabeth, had something ready on her lips.

‘An abomination.’

Goodwill nodded. ‘Yes.’

‘Idolatry. An offence to the Lord. In this house.’

Patience glanced quickly at her brother then lowered her eyes again, before taking her lead from her mother. ‘Idolatry.’

Nathaniel ignored his sister’s look. He was still watching his father, waiting. At last it came.

‘And you, boy, what did you know of this?’

Nathaniel stammered. He could feel his mother’s eyes on him, and he knew the stammer would anger her all the more. ‘N-nothing. I knew nothing of it, F-father.’

Elizabeth Crowe’s voice was cold. ‘You slept but three feet from him, how could it be that you did not know of this?’

Nathaniel lowered his head and said nothing. It was better, always, when he said nothing.

‘He must have stolen it,’ said Patience, emboldened. ‘He had the look of a Papist, or a thief.’

This Nathaniel could not tolerate. ‘Gideon is no thief.’

‘So what has happened to Mother’s bloodstone ring?’

Nathaniel screwed up his face in sudden frustration and annoyance. ‘What?’

‘Mother’s bloodstone ring. It’s been missing since the day before he disappeared. Is that not so, Mother?’

‘You didn’t tell me of this . . .’ said Crowe to his wife.

Elizabeth’s mouth scarcely moved when she talked. Not like those other times, when she preached, thought Nathaniel. Not like when her voice filled a room or churchyard, inflamed her hearers, stopped passers-by in their tracks. Here, in their home, about the streets of Aldgate, Elizabeth seldom spoke, and her voice, when she did, was low, her words slow and something terrifying. ‘It was a trifle,’ she said, ‘a vanity. Why should I concern you with such a thing when you are so engaged on Godly works, with the major and others?’

‘All worldly possessions are trifles, vanities,’ Goodwill replied. ‘But theft is a sin, regardless of the value of the thing stolen.’

Elizabeth said nothing. Nathaniel knew though, that the ring, the cheap, old ring, had belonged to his grandmother, Goodwill’s mother. Nathaniel could just remember his grandmother. She had been the last person, before Gideon Fell had walked into their lives, to brave Elizabeth Crowe’s bile to the extent of being kind to him.

Nathaniel tried to glance at the picture his father had brought out from beneath Gideon’s straw mattress. He hadn’t lied – Nathaniel never lied – he’d never seen the picture before, hadn’t known about it. He’d seen Gideon put things there sometimes – not the picture, other things – but Gideon had told him it was better for him not to know about these things, not to ask, and so he hadn’t.

Nathaniel didn’t like the picture; it was dark, and something in it frightened him. A dark tangle of trees, rocks and bushes. Goodwill held it facing out a moment and Nathaniel could see it better. Men sleeping at the base of a rock. Three men sleeping, but another awake. He knew then what it was. It was idolatry, a false image, a graven image, the depiction of Christ. Nathaniel knew that, he had been taught it all his life. But still he wanted to reach out to the wakeful man and say, ‘I’ll stay with you, I’ll watch with you.’ He knew what was going to happen to the man. It was the Garden of Gethsemane.

‘What will you do with it?’ Elizabeth Crowe said to her husband.

‘What do you think?’ he said. ‘I’ll keep it for now. There is a sign in this, somewhere, I am sure, or I would not have found it. I will keep it until I better understand it, and why Gideon Fell came here.’

Elizabeth nodded, and Goodwill, rolling the canvas into a scroll, left the small almshouse chamber that his son had for a time shared with Gideon Fell and returned to his work across the yard.

The room was still disordered from Goodwill’s search, the cot upturned and the bedding on the floor. Elizabeth surveyed the place a moment then looked to Nathaniel. ‘Clear it up,’ she said, and turned to leave, Patience in her wake.

As she passed him, his sister paused and murmured, ‘So much for your friend, now.’

Nathaniel had had a bellyful of her. ‘G-go to Hell, Patience,’ he said.

*

In Samuel Kent’s Coffee House on Birchin Lane in the heart of the city, all the talk was of Parliament. Parliament holding out against Cromwell, refusing to recognise his right as Lord Protector, threatening to cut the army, wrest it from his control.

‘But they can’t expect Oliver to give up the army,’ said Samuel, the old soldier who ran the coffee house. ‘He can’t govern without it.’

‘Oliver has no intention of governing without the army,’ responded Elias Ellingworth, who’d been holding court. ‘Parliament, though, he would happily do without. It cannot be long before he claims Divine Right.’

There was an uneasy shifting on the coffee benches at this, and a lull in the conversation that was shattered only by the arrival of Gabriel, the coffee house boy. He had been at Custom House Key, noting the day’s prices for the merchants who called into Kent’s in the course of the day, too busy to see to such matters themselves. Samuel’s niece Grace had been teaching Gabriel his letters, and he carried the worth of all the stocks of the day in his head, ready to list them on the board Samuel had hung up on the wall. Today, though, Gabriel was out of breath, having run faster than ever all the way back up to Birchin Lane from the river to be first with the news, and there wasn’t a figure still in his head when he got there.

‘Glory be! What on earth is it, boy?’ said Samuel when Gabriel had skidded to a halt at the top of the coffee house steps. ‘Is it an armada?’

Gabriel took a moment to get his breath, shaking his head vigorously to emphasise the import of his news. ‘No.’ Then he hesitated, a new and terrible thought come to him. ‘But maybe . . .’

A merchant, George Tavener, was on his feet. ‘Good Heavens, lad, take a seat and tell us what the matter is.’

A stool was thrust beneath the panting boy, and at last he had gathered himself enough to speak. ‘A monk. Dead a hundred years. All bricked up in Blackfriars.’

Elias Ellingworth, the lawyer, looked at the child quizzically. ‘That’s hardly news, Gabriel. There’ll be lots of old Dominicans buried there. There are places still in London where you’ve a good chance of digging up a monk’s skeleton every time you put a spade in the ground. A few are bound to be turned up now and again at Blackfriars.’

But Gabriel shook his head all the more emphatically. ‘Not a skeleton. Fresh as you or Mr Tavener there. But dead, and all bricked up there since old King Henry put his Spanish queen to trial in Blackfriars to get rid of her, before he could get rid of the monks too.’ His voice became quiet with terror. ‘Now they’re coming back, to get their revenge, Dan Botteler says.’

‘Dan Botteler!’ said a haberdasher, tutting as he put on his gloves ready to go back to his shop. ‘Dan Botteler’s mother dropped him on his head long ago, and he hasn’t spoken a word of sense since.’

The others, having similarly lost interest in the boy’s story, went back to their coffee and their pipes.

‘But what if it’s true?’ Gabriel looked around him, beseeching.

‘You’ll not need to worry about it, true or not, if you don’t get back down to the quayside double quick, to get the prices of Mr Tavener’s stocks.’ Samuel Kent brandished his stick threateningly. ‘Better take your chances with Queen Catherine’s ghost!’

The boy was up and out in the streets again before the laughter from the coffee drinkers had died down.

‘Strange, all the same though,’ said Elias. ‘A body to lie uncorrupted so long. There are ways, I have heard, of preserving them, but behind a wall? I cannot fathom that.’

‘Don’t trouble yourself over it,’ said Tavener, ‘it’ll be all over the Intelligencer by Monday, with every lurid theory you could want.’

‘Yes,’ said Elias, gathering up his papers for his business in the courts, ‘and never a word more said about Protector or Parliament.’

*

In the depths of Blackfriars, Damian Seeker looked upon it. Walled in alive. Dead now. Very thoroughly dead.

The stonemason was prattling, never taking his eyes from the recess he’d unwittingly revealed in the far wall. ‘Heard of it before, mind, in bogs and suchlike, on the moors, bodies kept perfect, hundreds of years. Never seen it. Not till now.’ The man was rooted in the doorway, reluctant to move any closer to the corpse, as if fearful the black-robed figure was not quite dead.

Seeker stepped impatiently past him into the small, roofless chamber that, many incarnations ago, might have served as private chapel to the priory, but was now scarcely fit for the stalling of pigs. The stonemason continued to babble, addressing himself now to Seeker’s sergeant, Daniel Proctor.

‘Lack of air, I suppose, that preserved it that long. I mean, the Blackfriars haven’t been hereabouts for a hundred years or more, have they? Lack of air.’ He nodded confidently, rubbing his arms in an attempt to stop the shivering. ‘Or a miracle?’

Proctor shot him a warning glance. Talk of miracles was not to be encouraged, and would certainly not improve Seeker’s mood. The man shut up.

Seeker called Proctor over to him. ‘Take a look, Sergeant,’ he said, before glancing over his shoulder at the stonemason. ‘And you, wait outside.’

Once the fellow had gone, Seeker took his knife from its sheath and carefully used the flat side of the blade to draw the cowl back from the face of the dead man. There was a slight tug as the black worsted reluctantly came away from the dried blood stuck to the man’s hair. The light in the chamber was poor, but sufficient for their purpose. Daniel Proctor was no stranger to the sight of corpses in varying states of decay, but he took a step back from what Seeker’s knife revealed. ‘It isn’t possible.’

Seeker nodded slowly. ‘It shouldn’t be possible, yet it is.’

‘But how can it be?’

‘That I don’t know. But here isn’t the place to find out. Guards!’ he shouted, and four of his men came quickly into the dilapidated chapel. ‘You two, get a cart and covering to take this body up to the coroner’s court at Old Bailey. You, fetch the alderman of Farringdon Ward, and tell him to get himself up there.’

‘What will you tell him?’ said Proctor.

‘That the body was preserved through lack of air. That it is being moved under guard for fear of some pestilence. That will keep the curious well back.’

‘And if the people start to talk of miracles?’

Seeker looked again at the face of the man revealed by the cowl. ‘Let them. Better talk of miracles than the truth.’

‘Whatever that might be,’ said Proctor quietly.

‘Aye,’ agreed Seeker, ‘whatever that might be.’ He moved closer, the better to examine the man’s face. ‘I could do with Drake’s view on this. Bring him to me at the coroner’s.’

‘What should I tell him it’s about?’

It hadn’t occurred to Seeker that Proctor didn’t know Drake’s discretion as he did. ‘He won’t ask. Just bring him.’

Once his sergeant had gone, Seeker went to stand in the doorway of the old chapel, blocking off the sight inside from curious eyes. The stonemason and his apprentice had been taken for questioning, but Seeker knew enough of masonry to know that the brickwork masking the body had not been left undisturbed near a hundred and twenty years, since the Dominicans, the black-robed friars, had roamed freely from this place that still bore their name.

Seeker turned his back to the corpse in the wall and surveyed what Blackfriars was now. Derelict, damp, its walls gradually falling into the stinking Fleet. How was it this had ever been a place of God, a parliament, a court for Henry Tudor’s queen? No pleasant gardens left around the crumbling cloister, no richly robed ambassadors of foreign kings to be flattered and painted here, no angelic voices rising from the choristers of the Chapel Royal. It was as if the depravity of Bridewell facing it across the Fleet had crept along King Henry’s gallery, dragging with it the spores of an irresistible decay.

‘Pull it all down, best thing for it,’ Daniel Proctor had said when they’d arrived, summoned by a sharp-eyed constable who’d guessed there might be more to the stonemason’s macabre find than met the eye. Stamping his feet to fend off the chill of the freezing January morning, Seeker had grunted his agreement. Whatever had drawn the Dominicans to this site on the Thames four centuries ago was long disappeared, violated, built upon and built upon again. At the last it had been a theatre, shut up for years now, a place of nuisance and debauch, until the Commonwealth had put an end to it. London needed cleansing, and sometimes the only way to do that was to pull down and begin again.

Before the cart bearing the covered corpse had even cleared Ludgate, rumour as to what lay beneath the heavy sacking had begun to run. It was the last friar, bricked up for that he had refused to leave; it was the princes, starved to death in the Tower by their uncle of Gloucester, their poor young bones found at last; the thing had no head – a lover of Anne Bullen; it was Plague. That last they liked the least; that last kept them further from the cart than the others had done; there was no good story to be told if the thing beneath the sacking was that last.

Up at Old Bailey, there was a great deal of low murmuring amongst the officials of the coroner’s court. They should be given their place: this was not a matter for the army. But any protestations the alderman of Farringdon Ward or the coroner of Middlesex had considered airing died on their lips when they saw Seeker follow his soldiers, bearing their burden, into the building. Lawyers and ward officers stepped further into the shadows, grateful not to be noticed, wary already about what might lie beneath the covering of the stretcher. ‘Dear God,’ murmured one, ‘is it not enough that he pursues the living?’

The arrival a few minutes later of the apothecary John Drake did little to quell the air of apprehension growing in the corridors and doorways.

‘Drake. Why have they called him? What need has a dead man of an apothecary?’

The coroner regarded the alderman with a mild contempt. ‘You believe Drake is an apothecary? Have you ever been into his place on Knight Ryder Street? Do you know anyone who has? Whatever alchemy he practises there, there is nothing honest in it.’

The men stepped back as Drake moved quietly past them. He was tall, and his sweeping black robe did not quite mask an unnatural thinness. A slight stoop further shaded his already shaded eyes from the curiosity of observers. His sallow skin and long black curls caused many to declare him a Greek, and Drake was happy enough to let the assumption pass: there were too many still in Cromwell’s England who did not share the Lord Protector’s desire to readmit the Jewish people from their five-hundred-year banishment. Even without the distinctive cap and robe of his craft, Drake carried about him an air of mystery, and there were those who suspected his alchemical practices owed more to old magic than to the new science.

‘You mark me,’ whispered the alderman, turning from the coroner to his constable, ‘a monk dead a hundred years and more, his body scarce corrupted, and now that fellow called upon. There has been something unnatural here.’

Seeker, too, was of the view that he was in the presence of something unnatural, but his thoughts had little to do with alchemy, or miracles, or talk of magic. He nodded briskly as Drake was brought into the room, and had everyone else but Proctor leave it.

The apothecary was no more disposed to unnecessary preliminaries than was Seeker, and went straight over to the body, trailing welcome scents of bergamot and jasmine to contend with the pungent smells emanating from the cadaver that had indeed begun to decompose. Seeker followed him, while Proctor waited by the door.

‘Tell me what you know, and what you wish to know,’ said Drake.

‘This corpse was uncovered less than three hours ago, behind the wall of a building in Blackfriars long out of use, by the mason inspecting it for demolition. It was clothed as you see it now.’ There was no need to ask if Drake recognised the type of clothing; Seeker knew it was the Dominicans, the friars of the Inquisition, who had driven Drake’s family to London in the first place.

Drake nodded. ‘The robes of a Dominican friar.’ The apothecary walked around the table on which the body had been laid, sometimes bending to inspect it a little more closely, sometimes using a thin wooden baton to gently ease clothing back from flesh.

‘And what is it you would know, Captain?’ he said, apparently concentrating on the bare feet that extended beyond the hem of the robe.

‘How old is this body? How long has this man been dead?’

Drake turned his head towards Seeker, raising an amused eyebrow. ‘The body, I would say, Captain, is around as old as yours. Forty, forty-five years old, perhaps. Many decades younger than his clothing, which as you see,’ he said, indicating points on the sleeves and around the neck area, ‘has begun to rot in parts, and been troubled by moths and, I suspect, mice. As to how long he has been dead,’ he straightened himself, ‘a matter of a very few weeks.’

Seeker nodded. ‘And the manner of death?’

Drake peered closely at the man’s mouth, the tips of his fingers and toes, then lightly separated some of the hairs at the back of the man’s head. ‘Unpleasant. You see there has been bleeding, though not any great amount, from a blow to the back of the head, but the skull is not cracked and I don’t believe that is what killed him. The passage of time muddies the picture, but I believe this man died through suffocation. Deprivation of air.’

‘Strangulation?’ But Seeker thought he already knew the answer to that.

Drake shook his head, and indicated the man’s neck, and the lack of chafing or bruising around it, before carefully raising one of the corpse’s hands, and indicating the fingertips. ‘You see that his neck shows no marking of strangulation, yet his fingertips are worn more than ragged – the skin has almost all been scoured away. There are traces of soot in the creases of his hands, and,’ here stooping to examine the man’s nose, ‘his nostrils. More than in the common run of things. And his nails,’ he straightened himself and brought his own index finger to the nails on the fingers of the left hand, ‘you see they are badly broken and worn down, what’s left of them filled, I suspect, with the same manner of crumbled brick and powder you will find on the wall behind which he was enclosed.’

So it was as Seeker had suspected. ‘He was bricked up in there alive.’

Drake let the dead hand fall. ‘That at least would be my assessment. Also, I doubt very much that this man was a wandering friar.’

Seeker knew he hadn’t been, but was curious all the same. ‘What makes you say that?’

‘His feet. They are not the feet of a man who has walked the world in sandals.’

‘No,’ said Seeker. ‘They are not. Thank you, John.’

Drake inclined his head slightly and left without further farewell, other interests already calling him.

Daniel Proctor approached the figure laid out on the table once more. ‘It’s him, then?’

‘Looks like it.’

‘What will Thurloe say?’

Seeker considered. Whatever Thurloe had to say, he suspected, would go halfway to explaining why the man in front of them had been bricked up alive in the old priory of Blackfriars. ‘That is what I intend to find out.’

*

Thurloe would not be found in his usual offices at Whitehall, that Seeker already knew. The Chief Secretary, on whom the government of England, the survival of the Protectorate, the security of the Lord Protector himself, so much depended, was ill. He had been ill for weeks, and refusing to countenance any retreat from the rigours of his office, until Cromwell himself had ordered him to betake himself to his bed, ‘And not in Whitehall, Thurloe, or I will set my dogs on you!’ Too ill to argue any further, Thurloe had left many instructions with his most trusted Under-Secretary, Philip Meadowe, and consented to remove himself as far as his old chambers in the attics of Lincoln’s Inn. Cromwell had decreed that all business meant for Mr Thurloe should be brought for the time being before Meadowe instead, but Thurloe had summoned Seeker to him before finally agreeing to leave in the litter that had been called for him.

‘You, Damian,’ he had said, applying all of his meagre strength to his grip on Seeker’s wrist. ‘You will come to me, if you come upon any business that is not for others to know of. You know the type of business of which I speak. You will not fail me!’

Seeker had known. Any business so dark, so far in the murk that its outlines could hardly be seen. What had been found at Blackfriars was of this business.

Seeker did not often have cause to be at Lincoln’s Inn, and he was glad of it. It was a pleasant place, he could see that, if you belonged in such places, but Seeker knew he did not. The gardens, with their high brick walls, their walks and arbours, their well-clipped lawns and pinned back roses were too precise, too ordered, there was no freedom in them. A place where nature was not loved but tamed, and Seeker, be he never so controlled, was too rough-hewn for such a place. Within the portals of Lincoln’s, its panelled walls, polished floors, corridors echoing with assured laughter, voices trained to expectation and ambition, the easy companionship of those who expected to get on in the world, the set of his face, the tread of his boot on a step, the very sound of his voice seemed to stop all of that in its tracks. The porter who met him didn’t even ask what he had come for. ‘I will take you to Mr Thurloe,’ he said.

After several turnings and stairways, they came to an attic corridor, and halfway down it the porter tapped lightly on a panelled door, giving his name. The door was opened, and Seeker had to stoop slightly as he stepped into a small, overheated sitting room. The porter nodded to him and left. Seeker recognised the manservant who could occasionally be glimpsed flitting through the corridors and doorways of Whitehall, always just in the background of the Chief Secretary’s daily life.

‘How is he?’ asked Seeker.

‘A little stronger, though far from fit for business, but I have instructions that you are to be let to see him, should you come. I pray you do not keep him long.’ The man disappeared through an inner doorway and a few moments later came through it again, more slowly, behind him a man younger than Seeker, not yet forty, and younger-looking still, like a curate or nervous junior lawyer. The man would have passed unnoticed in the street, like any other clerk or city-dweller of middling stature. Short and slight of frame, only the great dome of his forehead under long, lank fair curls, matted now to that forehead, marked him out as different, somehow. ‘Such a brain, Seeker, such a brain as holds the secrets of the world in its chambers,’ Cromwell had once said to him of his Chief Secretary. ‘’Tis a mercy God gave him to our side and not the other.’

Thurloe came closer into the light, and Seeker saw that the man on whom the Protector so depended was still gravely ill. Overwork, he thought. Thurloe was killing himself with overwork. The eyes were red-rimmed and the always-pale skin as rough and dry-looking as cheap paper. The small, thin hands that held within them the invisible strings of a network of agents and informers extending to the edges of Europe and the New World were clammy, and trembling. Seeker had seldom seen Thurloe outside Whitehall, or Hampton Court, for the Secretary was rarely prepared to remove himself far from the centre, the person of the Protector, and Cromwell still more rarely disposed to spare him. It was bandied in the taverns and the coffee shops that even the Lady Protectress was constrained to go through Thurloe first, should she wish to see her husband.

Thurloe made no comment as his servant helped lower him into the more comfortable-looking of the two chairs by the fire, and set a heavy woollen rug over his knees. The man then told Seeker to call him if the Secretary required anything and disappeared once more through to what Seeker supposed must be Thurloe’s sickroom.

‘Well, Damian,’ said the Secretary as the departing servant pulled to the door, ‘I’ll wager this is nothing good.’

‘No,’ said Seeker, ‘I don’t think it is.’

‘Tell me then,’ said Thurloe, reaching for the cordial his man had set on the small table beside him.

Seeker handed him the glass and waited for him to swallow it down, before telling him of the morning’s find at Blackfriars, and the apothecary Drake’s assessment of the corpse.

Thurloe listened without interrupting, saying only at the end, ‘A puzzle indeed, but I think there is something you have yet to tell me.’

Seeker took a breath, tried to keep the challenge out of his voice. ‘It’s Carter Blyth.’

Thurloe’s face registered something, a mild flicker, before he pursed his lips in thought a moment. ‘You are certain?’

‘Completely certain. As is Daniel Proctor, who also saw him.’

‘Hmm.’ Thurloe leaned forward suddenly. ‘You swore Proctor to secrecy?’

‘Of course,’ said Seeker.

‘Good.’

Thurloe sank back, his bout of animation having exhausted him.

‘I’ve left the body covered and locked under Proctor’s guard in the coroner’s court.’

The Secretary nodded, considered a moment before speaking again. ‘It is a bad business we have on hand here.’ He looked up at the still-standing Seeker, indicated the chair opposite him. ‘Sit, Damian. This may take some time.’

Seeker took a plain oak chair and sat down awkwardly, his helmet in his hands, the feet of his black leather boots closer to the fire than he would have liked. He waited.

‘You know that Carter Blyth was one of our agents in the Netherlands?’

Seeker nodded.

‘He kept a close eye on enemies of the Protectorate – Royalists colluding with foreign interests, especially the Spanish. Any Papists passing through. Presbyterians too. Radicals involved in the printing of incendiary works. Businessmen trading with the wrong people, showing an interest in the wrong sorts of goods.’

Seeker knew what agents of the Protectorate did in foreign cities – they joined the churches, patronised inns and coffee houses, traded at the bourse, insinuated themselves into the society and trust of those who might wish ill to Oliver’s regime, and gleaned information on those persons’ contacts in England. By such means, only a few weeks since, a plot involving London’s gunsmiths and other city merchants had been uncovered, and those involved pulled from their beds and slung into the Tower before they had had time to find their slippers or bid their wives farewell. The security of the regime depended upon its foreign agents as much as it depended upon the army at home. It would not have been the first time that an agent had been found dead, having clandestinely returned to his own shores. Seeker might well have believed this to have been the case with Carter Blyth, and would not have troubled Thurloe with it, had it not been for one detail.

‘Carter Blyth died in the gunpowder explosion in Delft three months ago.’ He looked bluntly at Thurloe. ‘You had me attend his burial in Horton churchyard.’

Thurloe was matter-of-fact. ‘It was necessary. For the sake of authenticity.’

‘Authenticity of what?’

‘That he was dead.’

Seeker said nothing.

Thurloe took a careful sip of his cordial. ‘Believe me, Seeker, it was not done to make you a fool, but because if you were there, no one would question our certainty. It suited me that Carter Blyth should be believed dead.’ He looked at Seeker directly. ‘I had other work for him to do.’

‘That was not an empty grave I stood by at Horton,’ Seeker said.

The Secretary was dismissive. ‘Some nameless fellow who’d died in Newgate. More use to the Commonwealth in death than he ever was in life, and none to miss him.’

Seeker thought of the worn-out woman who’d stood across the grave from him in Horton those months ago. ‘And Blyth’s widow?’

A shrug. ‘She doesn’t know. Grateful for the pension we gave her and didn’t ask too many questions.’

‘And,’ Seeker spoke slowly, ‘should we have any idea how Carter Blyth came to be walled up alive in Blackfriars, in the guise of a Dominican friar?’

Through his weakness, Thurloe smiled. ‘As well I have never needed to use you in diplomacy, Damian. I fear we have some work to do yet on your subtlety, but yes, you have come to the point. I can tell you what Blyth was doing back in London, but as to the rest? That I will require you to discover.’

It was over half an hour later that Thurloe finished. ‘You may ha

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...