- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

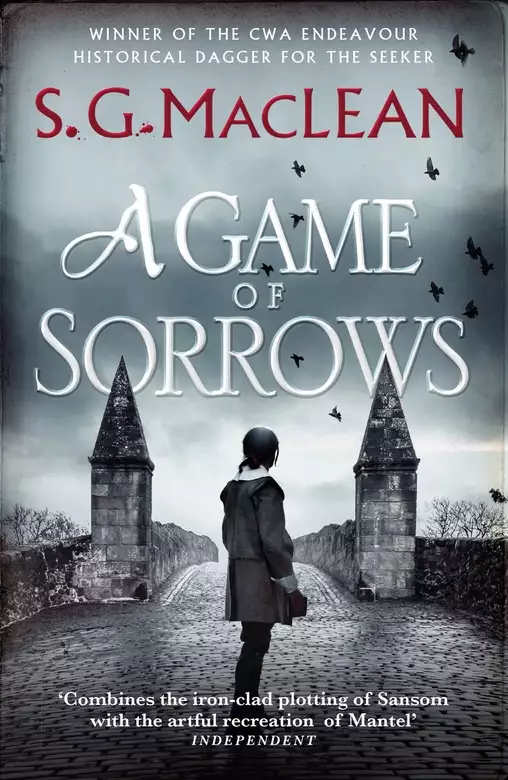

Second historical thriller in the Alexander Seaton series sweeps the hero back to his roots in Ulster, and a family living under a curse and riven with long-held secrets It is 1628, Charles 1 is on the throne, and the British Crown is finally taking control of Ulster. Returning to his rooms one night, Alexander Seaton is shocked to find a stranger standing there - a man who could be his double. His name is Sean O'Neill, and he carries a plea for help from Maeve O'Neill, forbidding matriarch of Alexander's mother's family in Ireland. All those who bear their blood have been placed under a poet's curse: one by one they are going to die. Only Alexander is immune, his O'Neill heritage a secret from all but his closest family. Alexander travels to Ulster, to find himself at the heart of a family divided by secrets and bitter resentments. As he seeks out the author of the curse, he becomes increasingly embroiled in the conflict until - confronted with murder within his own family - his liberty and, finally, his life, are at stake.

Release date: September 2, 2010

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 398

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Game of Sorrows

S.G. MacLean

It became clear to the administration that for English power in Ireland to be assured, Ulster must be brought under control. This was not simply a question of political or military conquest, but of cultural assimilation. The native Irish leaders of Ulster must be brought to acknowledge the sovereignty of the English Crown, and the people under their authority brought into conformity with English mores.

While the native leaders appeared at first to be willing to secure their own title to land in return for acknowledging royal authority, increasing awareness of the concomitant assault on the Gaelic way of life brought them to rebellion. The most significant of these rebellions was that led by Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, in what became known as the Nine Years’ War. The brutality and hardships of this war devastated Ulster. Tyrone’s ultimate submission in 1603, followed four years later by his flight to the continent with the Earl of Tyrconnell and other native Irish leaders, left Gaelic Ulster open to what English advisers had been urging for some time – not the Anglicisation of Ulster, but its colonisation.

Following ‘the Flight of the Earls’, the Crown initiated mass confiscations of native Irish land. Those who retained their lands held them on terms which greatly circumscribed their power and standing. Others, whose loyalty to the Crown was judged suspect, faced imprisonment, exile or death. Ulster was to be secured by the granting of the escheated lands to new landholders whose loyalty to the British state and the Protestant religion would not be in doubt. Pre-eminent in this new order were to be the ‘New English’ settlers, especially the ‘London Companies’ who were to re-establish and ‘plant’ the towns of Londonderry and Coleraine and vast tracts of land in the North with well-affected, mainly English or Scots, tenants. Only those judged most ‘well-affected’ amongst the native Irish were acceptable as tenants, generally on the poorest land and at the highest rents.

These ‘New English’ planters were distinct from the Catholic, Hibernicised ‘Old English’, having more in common with the Scots, who had been colonising areas of Antrim and Down for decades. Four peoples – native Irish, Old English, New English and Scots, with all their cultural, political and religious differences – were now left to forge a new society in what until the turn of the century had remained the most thoroughly Gaelic part of Ireland. Tensions and resentments were inevitable, and would eventually find expression in the carnage of the 1640s and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

Despite references to some actual historical figures and events – Randal MacDonnell, Earl of Antrim, James Shaw of Ballygally, Julia MacQuillan, the disaster of Kinsale, the abortive uprising of 1615 – and although the vast majority of locations mentioned in the text exist or existed, what follows is an entirely fictional account of how these tensions might have affected one family in Ulster in 1628.

Shona MacLeanJuly 2009

Coleraine, Ulster, July 1628

The bride’s grandmother smiled: she could feel the discomfort of the groom’s family and it pleased her well. This wedding feast was a sickly imitation of what such things should be – her father would have been ashamed to set such poor fare before his followers’ dogs. But no matter. The music had scarcely been worthy of the name, and of dancing there had been none at all, for fear of offence to their puritan sensibilities. It was a mockery of a feast; she should not have permitted it, regardless of what her husband had said. It might well be politic to pander to the ways of these new English settlers, but it was not the O’Neill way, not her way. She should have insisted that the marriage took place in Carrickfergus, and according to her own customs. But the girl too had been against it – like Grainne, she would reap what she had sown, and she mattered little, anyhow.

Maeve looked down towards the far end of the table – they should not have put him there; he should have had the place of honour – these people knew nothing. Finn O’Rahilly was resplendent in the saffron tunic and white mantle, bordered with golden thread, that she had gifted him for the occasion. He would be paid well enough too, although it was not seemly at such times to talk of money. Regardless of all that her granddaughter and her new husband’s English family had said, on this one point the old woman would not be moved. There had been a poet at every O’Neill wedding through all the ages and, despite all that had happened, there would be a poet at this one, to give his blessing on the union, to tell the glories – fallen, broken though they now were – of the great house of O’Neill. As Finn O’Rahilly rose and turned to face her, Maeve felt the pride of the generations coursing through her: her moment had come.

He spoke in the Irish tongue. Everything was still. All the guests, even the English, fell silent as the low, soft voice of the poet filled the room. Every face was turned towards the man with the startling blue eyes whose beard and long silver hair belied his youth. No hint of the chaos he was about to unleash escaped his countenance, and it was a moment before any but the most attentive auditors understood what was happening. But Maeve understood: she had understood from the shock of the very first words.

Woe unto you, Maeve O’Neill:

Your husband will soon lie amongst the worms and leave you a widow,

You of the great race of the O’Neills,

Woe unto you who lay with the English!

Your changeling offspring carried your sin,

Your son that died, with the earls, of shame.

Your daughter, wanton, abandoned her race and her name and went with the Scot.

Woe unto you, Maeve O’Neill,

Your grandchildren the rotten offspring of your treachery!

Your grandson will die the needless death of a betrayed Ulsterman,

Your granddaughter has gone, like you before her, whoring after the English – no good will come of it, no fruit, only rotten seed.

Your line dies with them, Maeve O’Neill.

Your line will die and the grass of Ireland grow parched and rot over your treacherous bones.

And the O’Neill will be no more.

The poet turned and left, without further word, and all for a moment was silence, save the sound of Maeve O’Neill’s glass shattering on the stone floor.

Aberdeen, Scotland, 23 September 1628

I had waited for this moment without knowing what it was that I waited for. The college was quiet, so quiet that the sounds of the life of the town and the sea beyond permeated its passageways and lecture halls unopposed by scholarly debate or student chatter. The shutters on Dr Dun’s window, so often closed at this time of year against the early autumn blasts of the North Sea gales, were open today to let in the last, surprising, golden glows of the late summer sunshine. The rays lent an unaccustomed warmth to the old grey stones of the Principal’s room, less austere now than it had been in the days of the Greyfriars who had walked these cloisters before us, in the time of superstition. The Principal’s words were as welcome to my ears as was the gentle sunlight to my eyes.

‘It is in you, Alexander, that we have decided to place this trust. It is greatly at short notice, I know, but you will understand Turner’s letter only came into the hands of the council yesterday, and response, not only by letter but in the form of the appointed agent of the town and college – yourself – must be aboard the Aurora by the turn of the tide on Thursday. We met in the kirk last night to discuss it, and our choice was not long in the making.’ He named a dozen names, all that mattered for learning and the word of God in our society. There had been a time when knowing that I had been the subject of such a conference would have engendered apprehension in me, for there could only have been one result of such a council then – censure, condemnation, exile. But that had been a long time ago, and in another place, and these two years past I had lived quietly and worked hard at my post in the college. My students in the third class, where I taught arithmetic, geometry, ethics and physics, liked me, I knew. I passed myself well enough with my fellow regents, and from Dr Dun, from the beginning, I had known nothing but kindness. My friends were few, and I did not seek to add to their number. William Cargill and his wife, friends both since my own college days, George Jamesone the painter, Dr Forbes, my former teacher and my spiritual father, and Sarah, since the day I had first met her, there had been Sarah. I seldom travelled, and rarely returned to Banff, the town of my birth, where I had friends also who were truly dear to me, and all the family I had in the world. Yet I did not like to return to the stage of failures past, so I did not go there a tenth of the times I was asked. I had had no fear, then, on being summoned to the Principal’s presence. Neither had I had any inkling of the news, the great prospect that awaited me there.

‘You are well versed in the German tongue, are you not?’ enquired the Principal.

I asserted that I was. My old friend Dr Jaffray, in Banff, had insisted on teaching me the language. He had spent happy years of study on the continent in his youth, and having no one else to converse with in that tongue, he had decided he would converse with me. Despite the ravages of the war which now raged over so many of the lands he held dear, he never lost sight of the hope that one day I would follow where he had first walked. And now, at last, his hope was to be fulfilled, but not, perhaps, in a way he might have foreseen. I was to sail on Thursday for the Baltic, and Danzig. From there I was to travel to Breslau and then Rostock.

‘Our brethren in the Baltic lands, in northern Germany, in Poland and in Lithuania, suffer greatly under the depredations of Rome and the Habsburgs: the King of Sweden struggles almost alone in their cause. Our brethren thirst for the Word and for their own ministers. Turner has written here, as the town of his birth, asking that we might accept two Polish students to study divinity for the next three years, that they might be sound and strengthened in their doctrine, and when they return to their homeland to fulfil their calling and spread God’s word there, that they should be replaced by two more. He has mortified to that cause the sum of ten thousand pounds Scots.’ Dr Dun paused for a moment to allow me to contemplate the incredible vastness of this sum.

‘Praise be to God for such a man and for such a gift,’ I said.

‘Indeed,’ said the Principal.

‘You wish me to escort the two students to Scotland?’ I asked, for the Principal had still not made clear what was to be my role in this enterprise.

He shook his head. ‘No, Alexander, some returning merchant or travelling townsman of good report could have performed that task. I wish you to travel to Poland to meet with Turner, and with his assistance, to seek out and find the two most worthy young men you can to fill these two places. I wish you to travel to the universities, to question the young men you find there on their learning, their soundness in doctrine, their strength of heart in adversity, their love for the Lord. When you find the two young men you know in your heart to be fit and right for this ministry, then you are to bring them back here with you. The council and the college will give you four months for the fulfilling of this task. Will you take up this trust, Alexander?’

The sounds from outside the open window were shut out by the contending voices in my head, all my own. Here at last, after false trails and false dawns, was the chance I had never believed I would be given. Here was the moment where Dr Jaffray’s hopes for me could be fulfilled. I would at last travel beyond the narrow bounds of our northern society, and all in the work of God and for my fellow man. Here was a chance fully to justify the kindnesses and the faith in me of Dr John Forbes, my mentor, and of Dr Dun himself, who had plucked me from my self-imposed obscurity in Banff for something better. Here was the moment, and I was as an idiot, in a stupor.

Dr Dun smiled kindly at me. ‘Do not tell me you mislike the commission, Alexander, for I can think of no other better suited to it. The loss of your own calling to the ministry – and I know you suffer from it yet – will make you a better judge than any other of those who would aspire to it. Will you go, boy?’

At the age of twenty-eight, it was a long time since I had been called boy, and never before by Dr Dun. The warmth unlocked my seized tongue. ‘Aye, Sir, I will go.’

There was much to be done and less than two days to do it in. By midday on Thursday, I would be aboard a merchant ship and bound for the Baltic. Many had gone before me, to increase and pursue their learning, to better master their trade, to escape present drudgery in the hope of a new and better life. I was not to be embarking upon the journey of a new life, but I felt that what the next few months would bring would change the life I had to come. There were letters to write, bills to pay, and farewells to make. It would be another week before the students began to arrive back in the town after their long vacation, and Dr Dun already had the matter of my temporary replacement in hand. I almost flew to my own chamber on leaving the Principal’s study, taking the granite steps two at a time and nearly knocking over the old college porter as I did so.

‘You’re as bad as the lads, Mr Seaton. I swear before God this place will be the death of me yet.’

‘You’ll be here when the sky falls in, Rob,’ I said, and ran on. The bare little chamber at the top of the college, looking out over the Castle Hill to the North Sea that would soon transport me to unseen lands, was all my own: I was not, like some of the younger unmarried teachers, constrained to share, and the solitude and simplicity had suited me well these last two years. The stone walls were unadorned, as was the floor. The only colour in the room came from the subtly hued books along the shelf, and the brightly coloured bedding which every married woman of my acquaintance deemed herself obliged to furnish me with. My unmarried state was a matter of great concern to all save one of them, and that one, the wife of my good friend William Cargill, had, I believed, guessed my secret. I had resolved in these past few weeks that it should remain a secret no longer, and was determined that what business I had to transact before I left for the eastern sea would be done with by tonight, so that I might devote tomorrow to persuading Sarah Forbes, servant in William’s household, mother to the beautiful, illegitimate son of a rapacious brute, that I truly loved her and that she must become my wife.

The remainder of the afternoon was spent on the necessary preparations for my departure, but by six o’clock most had been done and, as was my habit on a Tuesday evening, I threw on my cloak and went down through the college and into town, to William’s house on the Upperkirkgate. I did not go in by the street door but went instead by the backland. As ever, I was greeted first by Bracken, William’s huge and untrained hound, bought in the mistaken belief that he might one day again hunt as he had in the days of his youth. As he had learned, a busy young lawyer with the demands of wife and family hunts only in his dreams. The huge dog pressed me against the wall with his paws, and administered a greeting more loving than hygienic. I pushed him off, laughing, to attend to the other urgent greetings taking place around my knees. Two little boys, one as fair as the other was dark, clamoured loudly and repeatedly for my attention. It was little effort to sweep both of them up in my arms.

‘Uncl’Ander, Uncl’Ander,’ insisted James, the white-haired, two-year-old joy of my friend’s life, ‘make dubs.’ And indeed, the hands which he pressed to my face were covered in the mud the children had been playing with.

‘And what would your mothers say if I was to come into the house covered in such dubs?’

‘No tea till washed,’ said the serious little Zander, shaking his dark head. I kissed the hair on it. How could it be that I felt such love for another man’s child? But I did. I had loved him from the moment his mother had held him out towards me and, without looking at me and almost with defiance, told me she was naming him Alexander, Zander, after me. The child of a rape, the son of a filthy, bullying brute of a stonemason. It had been she, and not he, who had been banished the burgh of Banff in shame when her condition could no longer be hidden; she who had been sent to a loveless home where she was not welcome. And alongside the stones and the abuse hurled at her as she had crossed the river had been me. I had not known it then, I am not sure when I did finally know it, but at some point on our silent, reluctant journey together that day, she had utterly captivated me. Bringing her to the home of William and Elizabeth had been the best thing I had ever accomplished in my life, for them, for her, for her child, and for myself. But two years had been long enough; too long, and I was determined that on my return from Poland Sarah and Zander would leave the house of the Cargills and make their home, for life, with me.

The boys were wriggling down and began tugging at my sleeves to pull me after them into the house for supper. I stopped them by the well and we all three of us washed, although in truth my hands were dirtier after cleaning the two boys than they had been to start with. I steered the children past the still bounding dog, through the back door, and right into the kitchen. Lying in a large drained kettle on the table was a huge salmon, freshly poached and cooling, its silvered scales dulled and darkened, its flesh a wondrous pink, full of promise. It must have been one of the last of the season. I would relish it, not knowing what manner of food I might have on my travels to come.

At the other end of the table, bent over her flour board where she thumped with an unnatural venom at the pastry for an apple pie evidently in preparation, was Elizabeth Cargill. Instead of putting down her rolling pin and coming over to greet me by the hand as she would usually have done, she looked up tersely, gave a pinched, ‘Well. Mr Seaton,’ and returned with increased vigour to her thumping. Davy, William’s steward, sat in a wooden chair by the fire, plucking a bird. I looked to him for some explanation but was rewarded only with a narrowing of his thunderous brows and a muttered quotation from the book of Deuteronomy. The boys themselves seemed taken aback at my reception, but before we could make any sense of it, I heard the soft familiar brush of Sarah’s habitual brown woollen work dress against the flagstone floor. I turned to look at her, and she stopped stock-still where she was, her eyes those of one in shock. Her lips started to form some words and then she drew in a deep breath and stepped resolutely past me without a word.

I had had this treatment, or the semblance of it, before on occasion. One such incident had arisen from my failure to notice a new gown for the Sabbath, of a rich black stuff with white Dutch lace at the collar, sewn by Sarah’s own hand of gifts brought back to the family by William after a trip to The Hague. My protestation later to Elizabeth that Sarah was always beautiful to me had been to no avail, and the thaw of the women had been near two weeks in the coming. Another time, worse in that I knew it truly affected her more deeply, and that she had cause, was when Katharine Hay had passed through the town, staying a night at her parents’ town house in the Castlegate, on her way to Delgattie. I did not lie when I told Sarah that Katharine Hay, married now and with a child also, could be nothing to me, but I could not pretend that she never had been. This episode had been made all the more difficult by the fact that there had never been – and indeed still now there had not been – any open expression of love, any acknowledgement of expectation, between myself and Sarah. But I did love her, and I could not believe that she felt nothing more than gratitude towards me. I could not, in fact, believe that the desire I felt for her and the conviction I held to that she had been put on God’s earth to be my wife could have the strength they did were she not indeed meant for me. And once I had discussed my plans with William tonight and settled what business I needed him to perform for me, I would come here again tomorrow and tell her so. What this evening’s misdemeanour was, I could not even begin to guess, but I was confident that, as it had those other times, it would be carried away on the wind.

When she caught sight of Sarah, Elizabeth gave over her thumping and, passing me also, took her friend and maid-servant by the arm and proceeded with her out of the kitchen, though not before having said, very audibly, to Davy as she passed, ‘Would you tell Mr Cargill that Alexander Seaton is here, Davy, for it is surely not to see us that he visits.’ Davy favoured me with another glower as he rose stiffly from his chair and went to do his mistress’s bidding.

I stood alone in the centre of this well-loved room, silent now save for the crackling of the fire in the hearth, with the two small boys who now regarded me cautiously, in no possible doubt that I, Uncle Alexander, was the cause of their mother’s displeasure and therefore of all disruption of the usual life of the house. They said nothing, and the accusation of it burned into my confusion. The silence at last was broken by the arrival of William, the ageing Davy hobbling behind him.

‘Alexander,’ my friend said, smiling awkwardly. ‘It is good to see you. I had feared you might not come.’

‘Might not come?’ I enquired, confused. ‘I have been here to my dinner every Tuesday and Saturday evening for the last two years, and many another in between. Why in all the world did you think I would not be here tonight?’

‘Well,’ said William, hesitant and looking sideways in the direction of Davy, then down at the two boys. He looked away from me. ‘Davy, will you take the boys to get washed, and tell the mistress Mr Seaton and I will take our dinner in my study.’ The boys made to protest that they were already clean, but their protests were to no avail. I felt like protesting myself, but instead followed William silently through the house to the sanctuary of his study.

Once we were in, he shut the door firmly behind me and then turned to look at me, a weariness in his eyes. ‘What in the Devil’s name has been going on, Alexander? What were you thinking of? This house has been as the eye of the storm all day, and I dare hardly mention your name without my dear wife bringing down all the imprecations of Hell upon both our heads.’

‘William,’ I said, shaking my head, ‘I have no idea what you are talking about.’

He strode across the room and sat down heavily behind his desk, evidently angered. I had seldom seen William angry in the fourteen years I had known him. ‘What I am talking about,’ he said, enunciating each word clearly, ‘is you taking leave of your senses. It is all around the town, and not only amongst the women, that you were in not one but two drunken brawls last night, and that there was not a drinking house in the town where the serving girls were safe from you. I had it on authority that you kept low company the whole night, and that only the quick thinking of the ill-favoured Highlander you were with kept you from the sight of the baillies. I was half astonished not to find you in the tolbooth.’

I sat down, though unbidden, and tried to disentangle his words from what I knew to be true. ‘William,’ I said, screwing shut my eyes for hope of greater clarity, ‘I still have no idea what you are talking about. I spent last night in my room in the college, burning the candle low and deep into the night, alone, with a Hebrew version of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. I have not been drunk since you and I sat up half the night with Jaffray and his uisge bheatha when he was here in March, and the only Highlander I know is Ishbel, the wife of our friend the Music Master in Banff, and I believe were you to call her ill-favoured, he would run you through, he and Jaffray both.’

William’s face began to lighten a little. ‘So you were not at Jennie Grant’s place near the Brig O’Dee last night, gambling and getting into fights with the packmen?’

‘I have never gambled, as you know. And why on earth would I go to the Hardgate for food, drink or company?’ I asked.

‘And you were not at the Browns’ place, nor Maisie Johnston’s either?’ he asked.

‘No,’ I said, shaking my head, perplexed.

‘And there were no brawls, no bridling of serving girls, no Highlander?’ he persisted.

‘No,’ I said.

‘I have your word?’

‘You have my word, although I am not a little astonished you should need it.’

He sank back in his chair, convinced at last and visibly relieved. I myself now felt convinced of little, and a good deal unsettled. ‘William, what is all this talk?’

My friend took a bottle of good Madeira wine and two glasses from a press behind his desk that he thought Elizabeth was unaware of and poured us each a generous measure. He handed me my drink and smiled ruefully.

‘Alexander, I should not have doubted you, but this house has been in such an uproar of female fury all day that I had no peace even in my own head to think. Sarah returned from the morning market on the verge of tears and stayed there a good hour, apparently, before Elizabeth was able to draw from her what was upsetting her. The girl had been told by not one but half a dozen of the burgh’s finest scolds that you had been drinking and pestering women through the town half the night. She would not have countenanced their scandalmongering had she not had it from some respectable matrons too.’

He looked up at me, a little uneasy, and half looked away.

‘You know, Alexander, there are many in the town, and that number growing, who suspect you have a partiality for the girl. Och, Heavens, Alexander, I know it well enough myself; I see it in your face every time she walks into the room. But there are petty minds aplenty who would take little pleasure in seeing a servant girl, a fallen woman at that as they see her, being raised above her degree by a marriage to you. They would have been tripping over each other this morning to reach her first with the news of your carry on.’

I could feel the anger raging in my chest so I could hardly breathe. ‘Aye,’ I said, ‘tripping over each other and landing in a midden of their own making.’ I stood up. ‘So they think she’s beneath me, do they? Well, William, do you know why I have never yet spoken to her of it, of my feelings? Do you, William?’

My friend shook his head wordlessly, somewhat taken aback by the force of my rage. I took a breath and spoke slowly, deliberately. ‘It is because I know her to be so far above me in every way, other than that of the station that fate has thrown her to, that I am too scared to speak lest I hear her say she will not have me.’ At that moment there was a firm knock at the door, and Davy entered with a tray bearing our dinner. William had long assured me that Davy was not as deaf as he pretended to be, and I suspected from the look on his face that he had heard every word of my outburst. As he turned to leave us he gave me a look I had rarely seen from him before: it was something approaching respect.

‘Sit down, Alexander,’ said William after the old man had gone.

I did so slowly, looking all the while at some spot beyond my feet.

‘Would you not look at me?’ he said in frustration. So I did, and saw that his eyes were kind and there was a rueful smile about his mouth. ‘I would be the first to agree that Sarah is a much better person than those who would calumniate her. And remember, I myself married a maidservant. Since you brought her to our home, she has been a better help and friend to Elizabeth than I could ever have hoped for. She nursed my son when my wife was too ill to do it herself, and we both thank God every day that He sent her to us, through you, that our boy might live. Young Zander is as a brother to James, the brother he will never have.’ This I knew already, for Elizabeth had come so close to death in bringing James into the world that William had sworn he would never risk her in childbirth again. ‘N

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...