- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

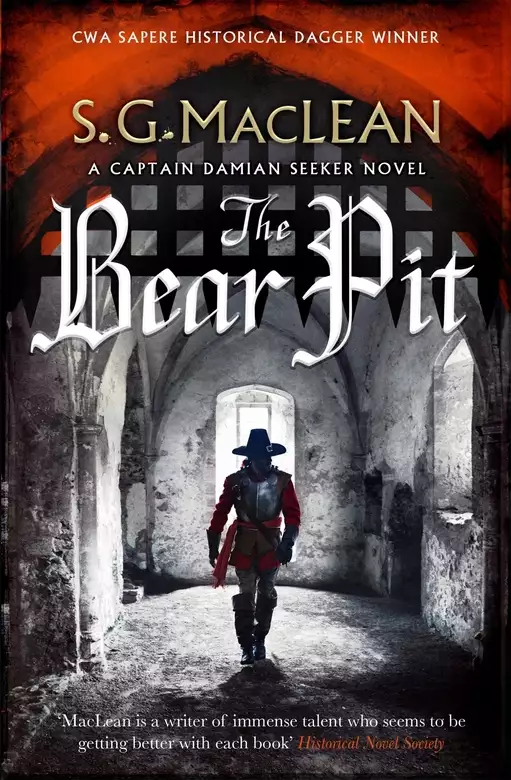

Synopsis

London, 1656: Captain Seeker is back in the city, on the trail of an assassin preparing to strike at the heart of Oliver Cromwell's Republic. The Commonwealth is balanced on a knife edge. Royalists and disillusioned former Parliamentarians have united against Oliver Cromwell, now a king in all but name. Three conspirators, representing these factions, plan to assassinate the Lord Protector, paving the way back to the throne for Charles Stuart once and for all. Captain Damian Seeker, meanwhile, is preoccupied by the horrifying discovery in an illegal gambling den of the body of a man ravaged by what is unmistakably a bear. Yet the bears used for baiting were all shot when the sport was banned by Cromwell. So where did this fearsome creature come from, and why would someone use it for murder? With Royalist-turned-Commonwealth-spy Thomas Faithly tracking the bear, Seeker investigates its victim. The trail leads from Kent's coffeehouse on Cornhill, to a German clockmaker in Clerkenwell, to the stews of Southwark, to the desolate Lambeth Marshes where no one should venture at night. When the two threads of the investigation begin to join, Seeker realises just what - and who - he is up against. The Royalists in exile have sent to London their finest mind and greatest fighter, a man who will stop at nothing to ensure the Restoration. Has Seeker finally met his match?

Release date: July 11, 2019

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Bear Pit

S.G. MacLean

17 September, 1656

Westminster Abbey, State Opening of Parliament

Boyes stared at the viola case, lying open upon the ground of the courtyard. It was scarcely credible. ‘A blunderbuss?’

Cecil was defensive. ‘I’ll not miss him. Not with this. Not at close range. Besides, what else would you have had me bring? I could hardly have walked openly through the streets with a full-length musket hanging from my shoulder, not today.’

Boyes lifted the weapon out of the case and examined it more closely. It was well made, certainly. The short, large-bore barrel was nicely turned, and the flared muzzle well proportioned for scattering the shot. One musket shot might miss a moving target, regardless of the skill of the marksman, but this would not, at close range. At close range. And therein lay the difficulty. A property closer than this house was to the east door of the abbey, from which Cromwell was shortly to emerge, could hardly have been found – its Royalist tenant had been happy enough to take off for his country estate well before today. But still there was the question of whether they would be close enough, and if they were not, how many innocents would suffer in the blast?

Boyes glanced again at the scaffolding they’d hastily erected against the wall of the yard, on pretence of building work being done. It would be substantial enough for their purposes, and they would not be up there long. In all the security checks carried out for this state opening of Parliament, no one had thought it necessary to check a second time the house of the quiet-living old Royalist colonel. So much for the location. The means was another thing, but while the choice of weapon might leave something to be desired, Fish had assured him that Cecil was one of the best shots in England – at least one of the best that could safely be invited to join an enterprise such as this.

The hubbub from the crowd outside had been building all morning, but within the walls of this small courtyard little was said between the three men. Boyes could feel a stillness in the air, a tightening in his stomach, such as they had all three known in the last hours before the commencement of a battle. On different sides, some of them then, but not now. This business had been a year and a half in the planning, first mooted in Cologne then agreed upon in Bruges. His mind went back to the small, smoky parlour of that house in Bruges, where an assortment of men who would never have thought to find themselves sitting at the same table, still less planning an undertaking such as this, had come warily together. Their plan would have its fruition within the next half-hour and they would go their separate ways again – Parliamentarians, Royalists, Levellers; men of so many different views and grievances, but they had all come to the one conclusion: Oliver Cromwell must die. What happened after that, only God knew.

The King had not been told, of course; so unbounded a horror of assassination – even of this usurper – had the murder of his father given him that such schemes were no longer put before Charles Stuart. But the popular rising the young King so waited upon would not happen, not without the crisis that the removal of the tyrant would provoke. Mr Boyes knew this better than most. They would proceed without the King’s knowledge, and then Charles would be presented with the fait accompli, and act as a king must.

Boyes studied ‘Mr Fish’ – or Miles Sindercombe, former Parliamentary soldier and now paid assassin, did his new London neighbours but know it. Fish had made all the preparations from his lodgings recently taken on King Street: selected the time, found the location, brought in a suitable accomplice in the form of Cecil. The presence of Boyes himself was not so much required for the execution itself, but for the aftermath. He would see to events in England, whilst others readied the King for his return to his kingdom.

Boyes brought out his pocket watch and opened the casing. The hand of Chronos went slowly closer to the hour. It was almost time. They had been careful today to arrive at the house by the back entrance, and only after the Protector with his council and family had already entered the abbey. Attention would be turned elsewhere, and Cromwell and his party would discover, when they emerged, that the short walk from the east door of the abbey past Westminster Hall to Parliament House was not quite as they had expected it to be.

Fish had begun to pace. ‘If we should fail . . .’

‘We will not fail,’ said Boyes. But he had already considered their escape routes. They could choose to plunge themselves in to the mêlée and confusion that would surely follow on their success, or leave by the back way, down the narrow alley to the landing stairs and then the river, where a wherry waited, then quickly to Southwark.

The hand of the figure on Boyes’s watch now pointed directly to the hour and he snapped the casing shut. ‘Now!’

Cecil began to climb the scaffolding, turning to take the blunderbuss once he reached the top. Blunderbuss. Donderbus, as the Dutch had it: thunder gun. And what a thunder would sound through Europe, if Cecil should find his mark.

Boyes could feel the excitement mounting in him, the old excitement, as he climbed the scaffolding behind Fish to take his place on the platform. From here, he could see Cromwell’s entire short route from the abbey to the hall. Beyond the hall to Parliament House he could not see, but that didn’t matter because Cromwell wouldn’t get beyond the hall. In the other direction, the crowd that had followed the Protector’s progression from palace to abbey was growing, starved of spectacle and eager to buy up the offerings of the numberless traders along their route. The taverns and alehouses of Westminster would be filled fit to burst today, in celebration of their Puritan lord and much-demanded Parliament. Boyes wondered how many of them had come seven years ago to gorge on the murder of their king, only to join in that dreadful groan when they saw the horror of what had been done. He did not wonder long, though, because suddenly the time for speculation was over: the great east doors of the abbey were opening. Their moment had come.

Cecil needed no prompting. His weapon was loaded with shot, and his hand steady as he lifted it. Fish and Boyes scarcely breathed as the doors were fully pushed back and he emerged, first, Cromwell himself. Of course. Everyone should know that the honour and the glory of this moment were his, this black-clad kinglet. A band of gold encircled Oliver’s hat, lest any should doubt what they had really done in raising a fenland farmer to be their chief of men.

Cecil glanced one last time at Fish for affirmation, but just as he lifted the gun to take aim, the crowd, which had been converging on the bottom of the abbey steps, surged forward, and Cromwell’s Life Guard was instantly around him, itself quickly engulfed by the tide of bodies. Fish cursed and turned to begin descending the scaffold, but Cecil stayed him. ‘A moment yet. There are gaps, and that gold band is a beacon through them.’

‘He will be wearing a secret beneath the hat.’

‘I know. I will make my mark lower.’

Boyes began to believe that it might yet be possible and then, as Cecil raised his arm a second time, a figure, a mass on its own almost, pushed through the Life Guard from their side and placed himself between Cromwell and everyone to the left of him. The Protector, hat and band of gold and all, was completely obliterated from their sight.

Again Fish cursed, but Cecil was angry now, and determined not to be deprived of his prey. ‘I’ll go through him,’ he said. ‘I’ll fell him and get to Cromwell anyway.’

‘It’s Seeker, Cecil,’ said Fish wearily. ‘Damian Seeker. You won’t go through him and you won’t fell him.’ He turned away. ‘Oliver Cromwell will not die today.’

Cecil made as if he would argue further, but Fish was no longer listening. Cecil lowered his gun and waited for Fish to reach the ground before passing it down to him and following. Only Mr Boyes did not go down immediately. He watched all the way, as the Life Guard and the procession pushed themselves through the crowd until the doors to Westminster Hall had been closed behind them and those of the crowd who had no good business being there were shut out. Boyes watched a moment longer, imprinting on his mind the dark mass, the huge form of the man who had come between Cromwell and retribution.

Fish was calling to him from below, urging haste that they might get to the wherry before any chanced upon them here. But Boyes continued to look towards where Cromwell and his impassable guard had been. ‘There will be another day, Captain Seeker,’ he murmured before he, too, descended the scaffolding. ‘You and I will have another day.’

One

The Gaming House

Six Weeks Later: End of October, 1656

Thurloe shook his head and handed the paper back to Seeker. ‘We are drowning in such information. Agents in Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, Cologne: every one of them hears something suspect of someone; every one of them writes of heated talk against the Protector. The continent is awash with disgruntled officers, Levellers, Royalists, Papists. We cannot chase down every piece of intelligence that comes our way. We have not the manpower. Corroboration is required. This,’ he looked again at the paper Seeker had handed him a few moments before, ‘this “Fish” is not a priority. Should Stoupe in Paris confirm the report, we will act further upon it, but until that time we do not have the capability.’

Seeker was not ready to be put off. ‘Stoupe is seldom mistaken, Mr Secretary, and he states that his information came from Bruges. It speaks of a Mr Fish in the area of King Street, suspected of plotting against the life of the Protector. It is not the first time I have come across the name.’

‘Oh?’ Thurloe’s interest was piqued.

‘Mr Downing’s clerk, Pepys, mentioned that name, more than once, in the days just before the opening of the Parliament.’

‘Which was six weeks ago, and nothing attempted.’ Thurloe’s interest was gone. ‘I know of this clerk of Downing’s – he is too often in taverns and over-fond of groundless gossip. Intelligence, Seeker: what we deal in is hard intelligence.’

Which is what this is, thought Seeker, looking again at the paper Thurloe had just put down.

The Chief Secretary was weary. ‘We are inundated with intelligence. What cannot be corroborated must take its place behind what has been. This is but a rumour of a rumour. We cannot run around half-cocked at everything we hear – as well put Andrew Marvell in charge.’

Seeker might have laughed at that, under other circumstances, but there was something in this he did not like the smell of. The source was a good one – he knew it, and the Secretary knew it too, were he not all but overwhelmed. But to countermand Thurloe’s orders was not an option: to blunder in where he had been told not to might upset operations of which Seeker was not even aware.

Thurloe had almost reached the door when he turned and cast a wary eye at the great hound stretched out in front of the hearth and blocking almost all the heat coming from Seeker’s fire. ‘That has the look of the beast I have seen lurking about the gardens of Lincoln’s Inn, with the gardener’s boy.’

‘It is, sir. Nathaniel is fearful it will wander into the city and fall foul of the ward authorities. The constables have been seized by one of their fits of vigilance and stray dogs are about as welcome as stray pigs to the good citizens within the walls at the minute.’

‘Though less flavoursome, I’d warrant,’ said the Secretary, throwing the animal another grim glance before leaving the room.

The door was hardly shut when the dog’s ears pricked up at the sound of a party of riders assembling in the courtyard below, and Seeker’s old sergeant, Daniel Proctor, calling instructions to his men.

Seeker opened the casement and called down to Proctor. ‘What’s on tonight?’

‘Gaming house. Bankside.’

‘Right then.’ Seeker felt a surge of energy. He’d been sifting reports and papers for days, weeks even, and the air in the room had become as oppressive to him as a half-ton weight. He hadn’t been on a raid in two months. ‘Have them fetch my horse. I’ll be down in two minutes.’

By the time he’d donned his cloak and hat, the dog was alert and already at the door. Seeker hesitated only a moment. ‘All right, come on then.’

Late October and autumn was finally ceding its place to winter. Along the Thames, the city had begun to huddle in upon itself. More manageable, in the winter, thought Seeker. There was a different quality to the cold and dampness of the air, tempers flared less readily and the fear of pestilence receded for a while. The dog bounded ahead of the riders with their torches. The way down to the horse ferry was boggy like half the rest of Whitehall, its water courses knocked askew by rogue builders as London crept ever outwards. A fug of fog and sea coal hung over the river, and the lights of the hundreds of boats plying their trade, carrying passengers and goods from one place to another, gave it the appearance of a constantly shifting, many-eyed sea-serpent.

The crossing to Lambeth was short and free of incident. The other watermen, whose mouths were often as foul as the silt over which they propelled their vessels, knew to give the ferry carrying Cromwell’s soldiers a wide berth. Landed at Lambeth Stairs, the horsemen turned northwards, and soon found themselves passing the eerie wastes of Lambeth Marsh. Across the river, the lights of Whitehall and the grand houses of the Strand glowed and flickered. Proctor shivered and even the dog was more alert as they made their way, shadowing the bend in the river, towards Bankside.

‘Cold, Sergeant?’ asked Seeker, keeping his eyes trained straight ahead of him.

‘The chill of the marshes,’ said Proctor. ‘Like having the souls of the wicked breathe on your neck.’

Seeker did not mock the sergeant for his superstition. It was a godforsaken enough place by night. The occasional light twinkled from a lonely dwelling or some rag-tag line of cottages that had grown up, somehow, amongst the bogs and pools of the marsh. He didn’t stop to wonder what might drive a person to live there. Disappointment, a course of life gone wrong somewhere, misfortune passed down the generations. They always went to the depths or the edges. The lights and vice and heat of Southwark and Bankside, where the citizens of London had long chosen to indulge the excess of their natures in taverns, brothels and baiting pits, would give way to the misery of the Clink and the Marshalsea, waymarkers on the road to the desolation of the marsh itself. Seeker, too, shivered, and picked up his pace.

Before too long, they were passing Cupid’s Stairs and the pleasure garden at the curve of the river, and the lights and buildings of Bankside came into view.

Seeker turned to Proctor. ‘So where is it, then, this gambling den?’

‘Old gaming house past Paris Garden, between the Bull Pit and the Bear Garden. Shut up long since, but we’ve had word that it’s come into play again – cards, dice, whatever they think is easily hidden. High stakes.’

‘Any names?’

‘One or two we’ve heard before – low-level Royalists, stay-at-homes, mostly. Nothing to exercise Mr Thurloe.’

‘He’s got enough to exercise him as it is. But if they don’t come quietly,’ said Seeker, flexing the fingers of a gauntleted hand, ‘I’m just in the mood for a spot of housekeeping.’

They began to pass houses and gardens, the sounds coming from doors and windows increasing the further along Bankside and towards London Bridge they got. Theatres boarded up, baiting arenas pulled down, the ‘Winchester Geese’, those long-protected women of the night, thrown a year since from their closed-down stews to mend their ways elsewhere, and yet the miasma of vice lingered. Regardless of the best efforts of the Protectorate, Bankside remained Bankside and Southwark Southwark.

They crossed Paris Garden bridge to a track past the market gardens that backed onto St George’s Fields. Proctor brought them to a halt in front of a closed gate in a wall that ran the length of several tenements. Seeker dismounted with three of the men and they tied up their horses, whilst Proctor motioned the other three to turn up the long narrow alley leading to the front of the property. ‘Count of sixty,’ Seeker said.

Proctor nodded and followed his men up the alley.

At twenty, one of the men levered open the gate, splitting lock from wood. By forty, as the alarm was raised inside the house, the soldiers were past a range of outbuildings and halfway up the yard. At sixty, Seeker was smashing through the back door as the fleeing occupants ran into Proctor coming through the front.

It was difficult to see much to start with. Apart from the embers in the hearth, the only light came from an oil lamp suspended over a square table covered in green baize cloth. The contents of an upended wine jug crept over the cloth and soaked the cards that remained there. Red hexagonal chips and small ivory markers spilled across the floor nearby. A wooden card-dealing box, its contents indiscriminately disgorged, lay on its side, and the distinctive frame of a Faro tally board, its edges shattered and its wooden buttons come to rest far across the room, had kept its last points. The few coins that the gamblers had not managed to scoop from the table as they fled glinted and dulled on the baize as the lamp swung above them.

At the edges of the room, Seeker was aware of sofas, draped in shawls that he suspected would be a deal less luxurious than first glance suggested. The place smelled like a cross between a bordello and a chop house. It was likely both, but Seeker had not the time to consider it for now. Almost over to the front door, he shot out an arm and hauled the hindmost gambler back by the collar of his very fine green velvet coat. As he did so, he caught a flash of movement on the corner landing of the stairs to his left. He twisted his captive’s arm up hard behind his back and threw him down against the table, which overturned sending the remaining cards and coins scattering across the floor to land at the feet of two over-painted, under-dressed women cowering by the chimney piece. ‘Watch them!’ he shouted to the soldier who’d come in behind him.

Seeker began to mount the stairs, moving quickly but carefully. A solitary torch burned in a wall sconce in the upper room. At the far end, a figure was desperately working at the latch of the window. At the very moment he caught sight of Seeker emerging from the stairhead, he hoisted himself up as if preparing to jump. Seeker was three strides into the room when the catch at last gave and the casement opened. His quarry had a foot on the ledge when Seeker drew his quillon dagger from his belt and let fly with it, pinning the flared sleeve of the gambler’s coat to the wall. Such was the man’s shock that before he had time to think or attempt to divest himself of the coat, Seeker’s hands were planted on his shoulders and turning him around to the accompanying sound of tearing silk and velvet.

Seeker looked at the complacent eyes in the handsome face and shook his head. ‘I knew it,’ he said through gritted teeth. ‘I just knew it.’

*

Ten minutes later, downstairs, the six gamblers, some of them bleeding from the nose or mouth and others nursing swelling eyes or fractured hands, had been manacled and the cart called to carry them the short distance to the Clink. The two drabs were still loudly denying that they were any such thing, even as they were being handed over to the ward constables for escort to the cellars of the White Lion, where they might spend the night with others of their sort. From the back yard came the noise of Seeker’s dog, barking.

‘He’ll have chased down a fox or some such,’ said Seeker.

‘He’s not the only one,’ said Proctor, cocking an eyebrow towards the righted table, to which Seeker’s quarry from the upper floor had been secured. ‘That one’s hardly out of the Tower five minutes.’

‘I know it,’ said Seeker. ‘Barkstead must be going soft over there.’ They both started to laugh and then stopped. The Keeper of the Tower and Major-General for Middlesex was anything but soft. ‘I’ll have a word with this brave lad though, then I’ll haul him over to the Clink myself.’

Proctor knew enough not to ask questions he didn’t need the answers to, and simply nodded before turning his attention to the loading of the other five prisoners on to the cart.

Once they had gone, soldiers and prisoners all, and the broken door closed as well as it could be behind them, Seeker pulled out a chair at the card table and sat down. He picked up a card, the jack of spades, and turned it over in his fingers, casually examining it. ‘So,’ he said at last, without looking at the man opposite him, ‘want to start talking?’

‘It was . . .’ the other man began. ‘You see, I mean I thought . . .’

‘Thought?’ said Seeker, smashing the card face down on the table. ‘I doubt you thought at all! Mr Thurloe took you on at my word, my word. You were to keep a low profile, pass quietly amongst your Royalist friends, make connections with people of quality and influence. You were, under no circumstances, to draw attention upon yourself.’

Sir Thomas Faithly, who had flinched slightly when Seeker’s hand had slammed onto the table, had recovered himself somewhat and attempted his accustomed easy smile. ‘I’m sorry, Seeker. I was . . . bored.’

There was a terrible silence for a moment, broken only by the continued barking of the dog in the yard. Seeker considered letting it in, but didn’t trust himself not to set the beast on Thomas Faithly. He took a deep breath. ‘Bored? You were bored?’ The last word was enunciated with such disgust that Faithly’s smile evaporated on his face. ‘Are you missing the Tower then? Fun and games there, was it? Or are you hoping to slip back off to your old playmate, Charles Stuart?’ Seeker paused a moment, in an effort to calm himself. ‘I can’t believe I wasted my time or Mr Thurloe’s taking you down here from the North Riding last year. I should have left you with the major-general in York, and let him show you what happens to captured Royalist spies.’

Faithly’s features tightened. ‘You know I’m not a spy, Seeker. Not for the Stuarts, anyway.’

‘Well you’re proving yourself a worse than useless one for us.’

Faithly made to move his hands, but was cut short by the set of manacles binding his wrists. He pulled his hands back. ‘I’ve only been out of the Tower two months, Seeker. These things take time. I’ve begun to make the connections Mr Thurloe asked me to, I’ve wormed my way into John Evelyn’s circle, for instance, tedious prig that he is . . .’

Seeker snorted. ‘You mean he’s more on his mind than drinking and whoring.’

Faithly flushed. ‘As do most of the King’s supporters. But no, Mr Evelyn never did seem quite at ease at Charles’s court at St Germains, and it has taken me long enough to counter the ill opinion he formed of me there. I’m beginning to make my way, make inroads into the trust of several persons of note, but for pity’s sake, Seeker, a man needs some diversion.’

‘Indeed. And how do you think news of this “diversion” of yours will play out down Deptford way?’

‘Down . . .?’ Faithly gave an uncomprehending shrug. ‘You mean at Sayes Court? Why should anyone at John Evelyn’s house hear about this? Is that not why you’ve kept me aside from the others?’

Seeker regarded the man a moment, puzzled, and then realised what Faithly was saying to him. He let out a short laugh of disbelief. ‘What? You think I’m going to tidy this up for you, to make it go away?’

‘But surely, Mr Thurloe . . .’

‘Mr Thurloe? If word gets out, and it will – your companions there looked none too sober, or discreet – that you were taken in a raid here, but that I saw to it that you were let off whilst the others were sent to the Clink until such time as the Southwark magistrates took an interest in them, how long do you think it would take your fine friend Mr Evelyn to work out that you were in Mr Thurloe’s pay?’

Seeker saw comprehension dawn on Thomas Faithly’s face.

‘You’ll go to the Clink tonight. You’ll damn and blast me and all my works, you’ll tell them I gave you another hiding for trying to run from me.’

At Faithly’s mildly alarmed look Seeker pulled a face. ‘You can pretend, can’t you?’

Faithly relaxed a little and nodded.

‘Most of all,’ continued Seeker, ‘you’ll keep your ears open. I’ll whistle up a magistrate and you’ll be out with a fine before tomorrow dinnertime. And you’ll keep your nose cleaner than old Lady Cromwell’s bonnet from now on, understand?’

Faithly drew a heavy breath. ‘I understand.’

‘Right,’ said Seeker, bending to undo the link securing Faithly’s ankle to the table leg, ‘we’ll see what’s bothering my dog and then you’re for the Clink.’

*

Outside, the fog from the river had made its way down the yard, but it took little effort to find where the dog’s barking was coming from. He was standing outside the door of a stone structure built against the far wall. Seeker briefly noted the strangeness of it: a stone outbuilding when the main property, like most of its neighbours, had been constructed almost entirely of wood. The dog’s hackles were up, but he wasn’t snarling as Seeker had sometimes seen him do with a cornered rat or other vermin.

‘Stinks like a French butcher’s down here,’ said Faithly. ‘Must be a dead animal or something.’

‘Probably,’ replied Seeker, passing the torch to Faithly before reaching down to calm the dog. Then he lifted his horseman’s axe from his belt and brought it down heavily to sever the padlock from the building’s wooden door. He pushed open the door and the dog bounded in ahead of him. That was when the snarling began. Seeker took the torch again from Faithly and stepped carefully inside, then he stopped.

‘What is it?’ said Faithly, making to come in after him.

Seeker shook his head. ‘Dear Jesus,’ he said at last.

He took another step forward, past the dog, and held up the torch that Faithly might also see. A moment later, Thomas Faithly who had fought in the wars and seen men shot through by cannon, was staggering back out of the door to void the contents of his stomach in the yard.

Seeker remained motionless, his eyes fixed on the floor at the far end of the outhouse. ‘Out, boy,’ he said at last.

The dog gave off its low snarling and cast questioning eyes at its master.

‘Out,’ Seeker repeated, and the animal slunk out.

Still holding up the torch, Seeker took another two paces forward. There had been no doubt, from the moment he’d stepped in here, what he was looking at: a human being who had been half eaten. At closer quarters, it was clear that what lay mangled on the beaten earth floor, chained at the neck by an iron dog-collar to the wall, one arm torn wholly away, was the remains of a man. Seeker crouched down and brought the torch closer to the gory mess of bloody flesh, bone and rags.

The legs were ravaged, the stomach all but gouged out, and half the face gone, but it was as if whatever had so savaged this man had reached its limits, been restrained somehow. The side of the face that was pressed against the dirt floor appeared to have been untouched, if spattered with blood, as was the remaining arm, also on that side. Seeker reached out and gently turned the head. The hair was sparse, and grey, as was the close-cropped beard. The skin was rough, and deeply lined, the horror-struck eye yellowed, as were the few teeth in the torn mouth. A man of between sixty and seventy years of age, he would have said. Seeker forced himself to look into that face a while, as if somehow to keep company with this nameless stranger in his last, terrible moments.

A sound from the doorway took his attention and he turned around. It was Thomas Faithly, wiping his mouth. Faithly’s voice was hoarse. ‘What in God’s name is this, Seeker?’

Seeker stood up, and cast around for a moment for a . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...