- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

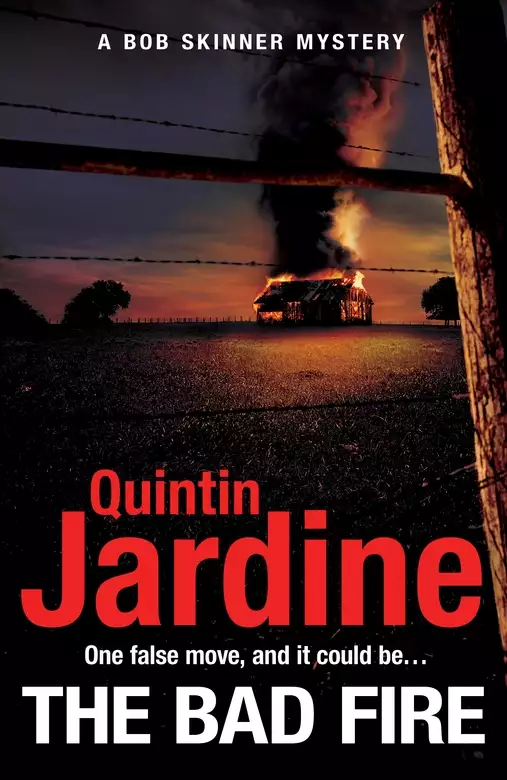

The gritty new mystery in Quintin Jardine’s bestselling Bob Skinner series, set in Edinburgh and the Scottish countryside; not to be missed by readers of Ian Rankin and Peter May.

Nine years ago, divorcee Marcia Brown took her own life. A pillar of the community, she had been accused of theft, and it’s assumed that she was unable to live with the shame. Now her former husband wants the case reopened. Marcia was framed, he says, to prevent her exposing a scandal. He wants justice for Marcia. And Alex Skinner, Solicitor Advocate, and daughter of retired Chief Constable Sir Robert Skinner, has taken on the brief, aided by her investigator Carrie McDaniels.

When tragedy strikes and his daughter comes under threat, Skinner steps in. His quarry is about to discover that the road to hell is marked by bad intentions . . .

(P)2019 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: November 14, 2019

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Bad Fire

Quintin Jardine

Threat and danger come with the territory I patrol, the place where I make my living.

It’s the nature of my work. Scottish criminal defence lawyers are guided by a professional principle that we can’t pick and choose our clients, and I have to adhere to that rule, difficult as it may be on occasion. Some of the people I have represented in court have been as utterly reprehensible as the crimes of which they have been accused, but even beasts have a fundamental right to the best defence available. Sometimes that’s been me, Alexis Skinner, Solicitor Advocate. Sometimes I’ve gone home and stepped straight into the shower to wash off the taint of the creep I’ve been doing my level best to return to society.

It wasn’t always like this. When I left Glasgow University with my brand-new law degree (Honours), I wasn’t bound for the high court, or any other level of the justice game. My first port of call was Scotland’s top corporate law firm, Curle Anthony Jarvis. It was headed at the time – still is – by my dad’s friend Mitchell Laidlaw. (Everyone knows my father; my father knows everyone. I’m sure that if Lloyd George was still around, they’d be acquainted.) Don’t go thinking, though, that I was the teacher’s pet; Mitch is a tough dude, and with him, the reputation of the firm is head and shoulders above any other consideration. My success as a corporate lawyer was down to my ability and the hard work that made them shedloads of money. And I was successful; the youngest partner in the firm’s modern era, and winner of a couple of legal awards along the way. I was a rising star, with a glittering and lucrative future set out before me.

Occasionally I would stare at the ceiling and ask myself, ‘Alex, why did you do something so profoundly fuckin’ stupid as walk away from all that?’

But I know the answer. It was my dad, wasn’t it?

I have met, but not for long, a couple of people – men, simpletons – who asserted that the legal avenue I chose at the beginning of my career was an act of rebellion against an authoritarian upbringing. Nothing could be further from the truth. My father, Sir Robert Morgan Skinner, QPM, remains the coolest guy I know. Yes, he had a ferocious reputation as a serving police officer. He scared the shit out of some very hard men. But at home he was Huggy Bear. My mother died when I was four, and he raised me to adulthood on his own. There were a few ‘aunties’ along the way, and one had some clothes in his wardrobe for a while, but he remained resolutely single until I was grown and flown. There are those who would say that he might have been better staying that way, for in the last twelve years he’s had three marriages, to two women, and another unfortunate relationship that did him no good at all, but he has settled down now, for good, I am certain.

He is growing older gracefully. I am thirty-one, which makes him mid fifties, but he has the look and bearing of a younger man. He acts like one too, and that worries me. He’s always had a tendency to draw trouble, and I suspect that in times past he’s gone looking for it. He has an image of impregnability, but he’s been shot, and sustained a near-fatal stab wound in a random attack; and he has a cardiac pacemaker installed as a result of a condition called bradycardia, which makes the heartbeat drop suddenly and without warning, in his case to zero. Not long ago, he was mugged in a garage by a Russian thug. It didn’t end well for the guy, but not before Dad had sustained a heavy blow to the head. He said it was nothing, but Sarah, my stepmother, confessed to me that it’s had an aftermath: occasional but severe headaches and a couple of dizzy spells.

When I was young, I wanted to be a teacher when I grew up, as my mother had been. Somewhere along the line that changed, and I wanted to be a cop. The motivation for my switch was Pops’ girlfriend, Alison Higgins, who was a detective inspector. She showed me that women could be significant players in a service that was evolving rapidly, moving away from the sexist, bigoted outfit that my father had joined, emerging as one where merit was rewarded and where the glass ceiling, while it still existed, was moving higher and higher. He was one of the drivers of that change, and so it was only natural that I expected when I announced my future career choice, with the unshakeable self-assurance of a fourteen-year-old, that he would beam with delight and support me.

‘Like hell you will!’ he barked at me across the dinner table. To say that I was taken aback, that’s putting it mildly. I couldn’t remember him ever raising his voice to me in anger, not even when I was at my most wilful – and I had been wilful, after Mum’s death and again as puberty crept up on me, a period of my life that her sister, Aunt Jean, had helped me through. It wasn’t only the vehemence of his reproof that startled me; there was something in his eyes that I had never seen before.

One of his team in the CID Serious Crimes squad, Mario McGuire, a detective constable on whom I had a small crush, had told me a story about being in the room when ‘the Big Man’ (Mario was huge himself) had interrogated a suspect in an armed robbery. ‘He never said a word, Alex. He sat there and looked at the suspect, stared at him across the table, never blinking, drilling holes in the guy with those eyes. It went on for minutes: Christ, I was scared, and I was sitting next to him. He never moved, never lifted a finger. The prisoner, who was no pussy, let me tell you, tried to stare him out, for maybe thirty seconds, but he couldn’t hold it, couldn’t look at him. The tension built and built until you could have cut in into blocks and built a house with it, until finally the prisoner threw both hands up and said, “Okay, okay, Ah was there! But Ah jist drove, mind. The other two had the shooters.” Then he told us where to find them, gave us a full statement and earned himself a couple of years off his sentence in the process.’

I had doubted that story – Mario was one of my father’s fan club, and I thought he was exaggerating – but that look, that glare made me a believer.

That’s not to say I was as compliant as the armed robber. I fired back at him. ‘It’s what I want, Pops! I want to be a police officer and you can’t stop me.’

He may have scared himself more than he alarmed me. In an instant, the fearsome detective superintendent was gone and Huggy Bear was back. The glower became a smile, and he winked. ‘Actually, love, I think you’ll find I can,’ he said. ‘But I’d rather it didn’t come to that, and here’s why. I’ve been a cop for about fifteen years, and in that time I have seen awful things, some of them so bad that I’ve done my best to un-see them. Every instinct I have as a parent makes me want to protect you from that.’

‘You don’t protect Alison,’ I pointed out.

‘That’s not the same: Alison had made her choice before I met her.’

‘What would Mum say if she was here? She’d have supported me, I’ll bet.’

He laughed. ‘I’ll tell you exactly what she’d have said. “No way, Josita. The pay’s crap and the hours are worse.” She’d have said the same about teaching too.’

‘Life isn’t about money or convenience,’ I protested.

‘Don’t knock either of those’, he countered. ‘But it’s more than that. Very soon now, I’m going to be head of CID, chief superintendent. By the time you leave university, there is every chance that I’ll be an assistant chief constable. If you were on my force, you’d be very difficult to manage. People are human; your line managers would struggle to know how to handle you. Do they favour you in the hope of finding favour with me? Or do they go out of their way to make life hard for you to show everyone else that there’s no special favours on their watch? It would be one or the other for sure.’

‘I could handle that,’ I promised.

‘I’m sure, but I couldn’t. If I thought you were having special treatment, I’d have to intervene for the sake of fairness to your peers. If it was the other way, do you really think I’d stand by and let some sergeant with an attitude pick on my wee girl? He’d be on the night shift in Pilton before he knew it, then his successor would make you teacher’s pet and I’d have to intervene again.’

‘There are other forces. I could join Strathclyde.’

‘You take sauce on your fish supper,’ he retorted, ‘not vinegar. You’re east coast not west coast,’ he explained. ‘And I’m not having you walking a beat in any of the choicer areas through there. Kid, I have no doubt that you would be an excellent police officer, but the odds are stacked against you. On the other hand, if Grandpa Skinner was still alive and you were having this conversation with him, his eyes would light up – as much as they ever did – and he would welcome you into his profession with open arms and a promise of a partnership in his firm before the ink was dry on your practising certificate.’

‘Did he do that with you?’ I asked.

‘Yes, but family law, worthy as it is, had no attractions for me. For you, on the other hand . . .’

‘Grandpa’s firm doesn’t exist any more.’

‘No, but there are others, and much bigger. For example . . .’

And that was the start of a process of persuasion that led me to the modern high-tech office of Curle Anthony Jarvis, the success I achieved there and the stellar future that was set out before me. Unfortunately, while we can fight our genetic inheritance for a while, long term it’s always going to win.

My father and I share a low boredom threshold, and as for my mum, from what I’ve learned, hers was practically non-existent. She got bored putting on her knickers, which was why they came off so frequently – a trait I have not inherited, I rush to say.

The process began at my last awards dinner. It was sponsored by a business magazine, and I had been chosen by a panel of ‘experts’ as ‘Young Dealmaker of the Year’, because I had led the legal team in the acquisition of a whisky distiller by a Chinese client of CAJ. The shiny statuette was presented by the finance minister in the Scottish government. She was fulsome in her praise as the flashes popped, and then it was my turn to make the obligatory speech of thanks. I hadn’t intended to say much, beyond thanking Mitchell Laidlaw for giving me the chance to shine, and paying tribute to my team. I did that, and that’s when I should have exited stage left and sat down; but I didn’t. I’d had a couple of drinks, and I was in a bad place with Andy Martin, my off-and-off love interest. He had stood me up with an excuse that I hadn’t bought for a second, telling him so in direct terms.

The mood carried over. ‘I should be prouder of this than I am,’ I continued, brandishing the bauble. ‘But I can’t be, because it’s ugly, probably made in Vietnam by a kid earning fifty pence a shift, and because it represents another step in the colonisation of my country, something to which we have become accustomed over the centuries.’ As cheers rang out from a drunk SNP table at the back of the hall, I pointed to the base of the trophy. ‘It says here,’ I continued, ‘on this wee plaque, “Scottish Business Awards”. With every passing year and every big deal like this one, that becomes less and less true. Just saying.’

Mitchell Laidlaw couldn’t look at me as I rejoined the firm’s table. A couple of the more senior partners did, and they weren’t happy. They couldn’t say anything, though: my dad had taken Andy’s place in chumming me. He stood as I reached my chair and drew it back for me. For a second I had a flash of dread that I had embarrassed him, for as long as it took for him to kiss me on the cheek and whisper, ‘Spot on, baby, spot on.’

The dinner was a Friday event; I spent the weekend alone, worrying about the reception I would have in the office on the following Monday morning, not least at the partners’ weekly meeting. As it transpired, nothing was said, but when I went back to my work area, I found that some comedian had pasted a photo of Mel Gibson, hair wild and face painted blue and white, on the wall behind my chair. Also, on my desk there was a copy of the Saturday Scotsman, a newspaper I never read, folded to display a report of my ‘outburst’. It identified me as the chief constable’s daughter, and carried a quote from an anonymous ‘spokeswoman’ commenting that it was simply ‘Alex being the Alex that we all know and love’. The firm’s PR consultant was female, so I pretty much knew who the author was, and also that she would not have dared say anything that hadn’t been authorised by Mitch himself. The thing that annoyed me was that it wasn’t true: I had never done anything but toe the official line, I had never spoken out of turn, and until then I had never shown anything but utter respect for the clients who paid our fees. My impromptu speech had surprised me as much as it had surprised anyone; it had come from a place I didn’t know existed and it had shaken me.

I determined that it would be a one-off and that I would put it behind me. I threw myself into my work and continued to complete my projects on time or ahead of schedule. Month after month I was at or near the top of the confidential profit-per-partner table that the firm’s management maintained. The Braveheart jokes stopped, and my views and comments on practice affairs were sought more than ever before. My star continued to shine.

But not at home. Professionally I was successful, but privately I was a mess. My relationship was in the crapper, I was lonely, and I could do nothing about it but spend hours in the Sheraton health club, punishing my body on treadmills, cross trainers and strength machinery.

I couldn’t even talk to my father about my feelings. He had his own issues at the time. The politicians were determined to force through the unified Scottish police service to which he was instinctively opposed, and his then wife, Aileen de Marco, was leading the charge. It’s the only battle he ever lost. Change happened, he couldn’t go along with it, and he walked away from the job that had been his life for all of mine.

Without knowing it, when he did that, he unlocked the door of my cage.

He broke the news to me over dinner. His sadness almost broke my heart, and yet when I woke next morning I felt happy that he had been strong enough to take the decision. It took me a couple of days to realise that I also felt happy for myself.

It took another couple for me to realise why. For the first time since I was fourteen years old, I had a career choice that in theory was limited only by my aptitude and ability. I had been brought up by a cop, among cops; now that the constraint of a chief constable father had been removed, I could be one myself. I had my degree, and I could take it where I wanted.

The euphoria didn’t last long, and reality bit. Although Dad had taken himself out of the game, I had grown up with most of the people who would be the big players. Worse, the team captain would almost certainly be Andy Martin. Topping all that off was the unfortunate truth that I wasn’t fourteen any longer, but a little more than twice that age, racing towards thirty at an alarming speed. If I joined the service, there was a fair chance I’d be the oldest person in my training college class, by several years.

The cage door slammed shut again, with a clang. I went back to work the next day, doing my damnedest to let nothing show, but it was a struggle. I felt lethargic and I knew very well that I was sliding down the profit-per-partner table, hour by hour. In an attempt to shake myself out of it, I decided to call my father; he was still a chief, head of the Strathclyde force against his better judgement, but as he had told me during that fateful dinner, he felt like a man on Death Row whose lawyer had finally given up on him.

‘I wouldn’t abandon him to the needle,’ I murmured as I picked up my phone. My mouth fell open, I gasped, and that cage door swung open again. ‘No, you wouldn’t, would you,’ I exclaimed, with a beatific smile that I didn’t even try to hide from my colleagues.

I knew in that moment what I wanted to do: I would be a criminal defence lawyer. I wasn’t fooling myself: it required a completely different skill set from that which had served me and CAJ so well. But it didn’t matter to me whether I would be any good at it. For the first time in my life, I understood what it was to feel a sense of vocation.

I went straight to Mitch Laidlaw’s office and told him of my decision to leave the firm and go into private practice. He’s a thoughtful and courteous man, so he didn’t laugh in my face, but after a couple of ‘mmm’s he asked, ‘Do you really want to spend the rest of your career defending drunk drivers in the sheriff court?’

‘My ambitions are a little higher than that,’ I replied. ‘I’m going to become an advocate with rights of audience in the high court.’

‘You can do that within this firm, Alex,’ he said. ‘I’ve been considering adding that string to CAJ’s bow for some time now, having counsel in house, and moving away from employing them as the need arises. Complete the training, and I’ll transfer you to the litigation department. You can replace Jocky Scott as senior partner there when he retires.’

‘I’m sorry, Mitch,’ I replied, ‘but I don’t want to do civil law. I want to establish a criminal practice.’

That’s when his mouth fell open and he stepped out of character. ‘What?’ he gasped. ‘You’re going to hawk yourself around the detention cells like the famous Frances Birtles and the rest of that crew?’

I smiled at his surprise. ‘Think of it as me setting up in opposition to my father. He locks them up, I’ll get them out.’

He fell silent for another minute, before saying, ‘Then God help the Crown Office. The prosecution’s in for a hard time.’

My partnership agreement specified six months’ notice, but as I’d expected, Mitch put me on gardening leave as soon as I had handed over my existing work; I didn’t have a garden, but that stuff is complex and confidential and couldn’t be left with someone who was heading for the exit.

‘You do know,’ he ventured, ‘that the qualifications include experience of a solemn procedure trial in the sheriff court?’

I didn’t. ‘How do I—’ ‘—get that?’ I was about to ask but he cut me off.

‘As it happens, I have a friend who has a solemn trial in Glasgow Sheriff Court next week. It’s a corporate fraud charge, and he’s in need of a junior with relevant experience. I can fit you in there, I think, and maybe into a few others along the way. You’ll have to work your nuts off, mind,’ he warned.

‘I would if I had any,’ I remarked. ‘Just one thing,’ I added. ‘Don’t tell my dad. You might not have tried to talk me round, but he would for sure, if he knew.’

I was halfway through the application process when I did tell him. To my surprise, he didn’t question my choice at all. He was so calm about it that I thought Mitch must have broken his promise, but he reassured me about that. ‘He never said a word. Truth is, love, I’ve been expecting this since that awards dinner; this or something like it.’

‘So I have your blessing?’

He laughed. ‘If you told me you were training as a pole dancer you’d have my blessing. Go for it. The high court needs you, Alexis. And who knows, now that I have time on my hands, you might find that once you’re established, you have a really cheap investigator.’

Actually it began with me doing some cheap investigating for him, but that’s another story. However, he was a huge help to me in developing my new career. I didn’t trade on his name, but I couldn’t avoid being his daughter and I have no doubt that it helped me. I did use him as an investigator whenever he was free, but only on work that justified his involvement. But as my practice grew, so did that requirement. Eventually I decided that I was asking too much of him, and that I should blood someone else.

Unfortunate choice of phrase, Alex.

One

By Scottish standards, it was an unusual summer. It had survived the first fortnight in May, continued into June, and was threatening to extend into July. Edinburgh’s city-centre shoppers were sweltering, the nation’s golf courses were turning brown in spite of their automatic watering systems and beach car parks were earning a small fortune for local councils all around the country.

‘Get you,’ June Crampsey laughed, as Bob Skinner walked past the open door of her office on the way to his own, dressed in shorts, sandals and a close-fitting blue T-shirt. ‘Not even the directors of our parent company in Spain dress like that. Nice legs, by the way,’ she added. ‘I don’t recall ever seeing them before.’

He paused. ‘Don’t you start,’ he replied. ‘Trish, the kids’ carer, said I look like the guy from Baywatch.’

‘Which version? David Hasselhoff or Dwayne Johnson?’

‘I like to think she meant the younger one.’

‘Could you do me a selfie?’ the managing editor of the Saltire newspaper asked. ‘I’m thinking of doing a photo feature in the next Sunday edition on unusual office attire.’

‘This doesn’t count as an office day for me; I was here all day yesterday, remember, Sunday or not, talking to Spain about the UK expansion programme. Sarah’s car’s had a recall, so I drove her to work, then thought I’d come in to check my mail.’

She looked at him afresh. ‘I don’t see room for a phone in that skimpy outfit.’

‘Left it at home, didn’t I? The heat must be getting to me, for I’m finding that I quite like being out of touch, from time to time. I don’t think I have been in years, since even before we all started carrying mobiles, or had them wired into our cars.’

‘That explains why your daughter was up here looking for you half an hour back. She asked if you’d call in on her if you showed up.’

‘I thought she was due in the high court this morning.’

‘The trial’s been postponed, she said. The prosecution have offered her client a plea deal.’

Skinner chuckled. ‘Which means that the Crown Office doesn’t think it can get a conviction. Okay, I’ll go down and see her.’

‘Don’t forget that selfie,’ she called after him.

He stepped into his own office; unlike that of his colleague, it looked towards the morning sun. The high-rise block was faced in glass that was meant to be heat-reflecting. It seemed to be doing its job, although the air-conditioning system was working full blast, ruffling the correspondence in his in-tray. Skinner was a part-time executive director of InterMedia, a family-owned company that was the proprietor of the Saltire, as well as titles and radio stations across Spain and Italy. He had been doubtful about the post when it had been offered by his friend Xavi Aislado. After a career in the police service, it had been a radical departure, but he had been persuaded – not least by the substantial salary – to give it a go. To his surprise, he had risen to the challenge, to the extent that while his contract specified one day a week, he spent at least three in his office, and had become effectively the managing director of the Saltire, as the board’s British presence.

He spent fifteen minutes reviewing his mail, physical and electronic, and acting on it where urgency was required, then headed for the stairs that led to the office suite he had secured for his daughter as her legal practice grew to the point where it could no longer be run from home or from a law library.

‘Bloody hell!’ Alexis Skinner laughed as her father appeared in her doorway. ‘Why didn’t you just put on budgie-smugglers and be done with it?’

‘You can talk.’ She was dressed in a sleeveless white blouse and a light blue skirt. ‘It’s well seen that you’re not on parade in the court. Have you got a result?’

She nodded.

‘You don’t look delirious about it.’

‘I’m not. My client and his wife had a physical confrontation, and she wound up in a coma. Attempted murder was never going to stick, given that she came at him with a carving knife; her prints were all over the handle and only one of his on the blade. But he did whack her after he had disarmed her. He says it was to subdue her, and I went with a self-defence plea on that basis. On Friday night the advocate depute rang me and said she’d take a plea to serious assault if I dropped self-defence. I told her to piss off and this morning they asked for a continuation that will almost certainly lead to the indictment being withdrawn.’

‘Great, you did get a result.’

‘Try telling that to Jack McGurk, the SIO on the case. Medical evidence says that he hit her three times, with his fist, but what it doesn’t say is whether he did that before or after he’d taken the carving knife off her. As I said, he put his hands up and admitted to hitting her once after she’d dropped it, and that was a glancing blow; his story was that the two disabling blows were struck when he was in fear of his life. Jack doesn’t believe that. Jack’s theory is that he beat her unconscious in a fit of rage after she confronted him about an affair, then slashed himself across the shoulder and put her prints on the knife.’

Skinner frowned. ‘But he can’t prove it.’

‘No chance. It’s his version against my client’s; reasonable doubt wins every time.’

‘So what’s your problem?’ her father asked.

‘I believe Jack’s theory too. I’ve spent enough time with my client to know that he’s a fucking psychopath; also, I have seen the previous convictions that the jury couldn’t be shown, including one for an assault that was serious enough for him to do eighteen months in a Young Offenders Institution. Despite all that, we have a woman in a chronic vegetative state, and the guy who put her there will be discharged.’

He shrugged. ‘As an ex-cop, kid, I agree with you. But it isn’t your fault. It’s Jack’s, for being too soft on the guy and failing to secure a confession. It’s the examining medic’s, for not being able to tell a self-inflicted wound from a real one. Either that, or you’re both wrong and it happened exactly as your client described. Either way, you have done your job to the best of your ability and should be as proud of yourself as I am.’

Alex winced. ‘I hear what you’re saying, Pops, but professional satisfaction is as much as I can muster. I have too much sympathy for the woman, whatever the truth of it. Her brain isn’t dead, but it’s massively damaged. Even if it did happen as Reilly – my client – says it did, it’s a hell of a price to pay.’

‘You’re not having second thoughts about your career switch, are you?’ Skinner frowned.

‘No, I’m not,’ she insisted. ‘When I went down this road, I knew that moral questions might arise. This is the first of them, that’s all I’m saying.’

‘Does it make you reconsider the offer that was made to you, to spend some time in the Crown Office as a prosecutor?’

‘No,’ she replied firmly. ‘I’m not ready for that yet. But it might make me think about representing victims of crime.’

‘I know plenty of those,’ Skinner murmured. He paused. ‘Is that why you wanted to see me, to get this off your chest?’

‘Partly, but there are a couple of other things. Firstly, there’s Uncle Jimmy’s memorial service on Thursday. Is Sarah going with you?’

‘Unless a last-minute job comes up that can’t be delayed, yes, she is.’

‘Can I tag along with you?’ she asked.

‘Of course. It won’t just be Sarah alongside me. June Crampsey’s going too, and her father, Tommy Partridge. I’ll have a row reserved for us; there’ll be a place for you.’

‘How about Andy?’ she murmured. ‘If he shows up, will he be welcome?’

He frowned. ‘Last I heard, Sir Andrew Martin was in America, lecturing and licking his wounds after his monumental fuck-up as the first chief constable of the national police service, or Holyrood’s Folly, as I like to call it. I doubt that the death of Sir James Proud got too much coverage in the US media, so he may not even know about it. He’s not on the guest list, that I can tell you. I know because his successor asked me to approve it on Chrissie Proud’s behalf.’

‘How is Lady Proud?’

‘She has vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s,’ Skinner said. ‘It hasn’t registered completely with her that Jimmy’s dead. Maybe I should give her his fucking dog back, as a substitute.’

Alex laughed. ‘Come on, you and Bowser are getting along fine, and the kids love him.’

‘The kids don’t have to clean up after him when we walk him.’

‘You could trust them to do that, surely.’

‘Like hell I could. And our village being what it is, the first time James Andrew neglected to bag a turd, the family would be named and shamed on the Facebook news group.’

She smiled at the thought. ‘I assume that you’ll be speaking at the service.’

Skinner shook his head. ‘No. I was asked, but I declined.’

‘You what?’ she gasped.

‘I said no. I’m history. Maggie Rose is the chief constable, and she served under Jimmy. It’s her place, not mine.’

‘But she didn’t know him,’ she leaned on the verb, ‘not like you did. You were his friend as well as his deputy. You spoke at Alf Stein’s funer

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...