- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

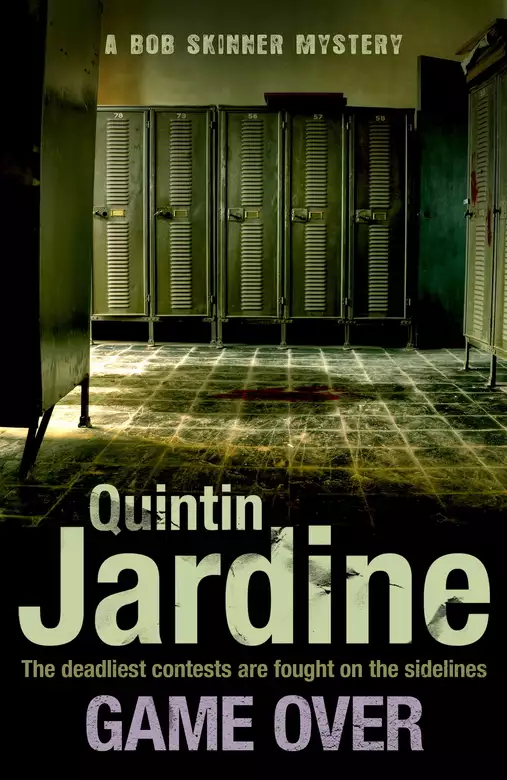

Game Over is the 27th gripping Bob Skinner mystery from crime master Quintin Jardine, author of Hour of Darkness, Last Resort, Private Investigations and many more.

When supermodel Annette Bordeaux is found battered and strangled in her Edinburgh flat, former Chief Constable Bob Skinner's old team instantly have a global case on their hands. The victim's husband, world-renowned footballer and recent Merrytown FC signing, is quickly discounted as a suspect. But there are others in the club with less watertight alibis...

Two years out of the game, Skinner can't help getting his hands dirty. And as his old team work to convict the prime suspect, his own daughter, Alex, is the lawyer tasked with leading the defence. The opposing sides must work to find the culprit while the press watch on.

But in this game, no one can be trusted, and there are murkier deeds still to uncover before the final whistle blows...

Release date: April 20, 2017

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Game Over

Quintin Jardine

‘Of all the gin joints, in all the towns, in all the world . . .’

‘What?’ Detective Sergeant Harold ‘Sauce’ Haddock exclaimed, cutting across his boss’s incongruous murmur.

‘Eh? Oh, sorry,’ Detective Chief Inspector Sammy Pye replied. ‘Don’t mind me. Casablanca,’ he explained. ‘My favourite film. Ruth and I watched the DVD last night. It’s Bogart’s line, and it struck a chord with where we are right now. Of all the crime scenes in all the towns in all the world, you and I have to walk into this one. This is going to be global, mate, and we are right in the spotlight, yet again.’

Haddock’s forehead creased in bewilderment beneath the hood of his disposable crime scene onesie. ‘It’s a murder, gaffer, okay.’ He looked at the body on the bed, face purple, dead eyes staring at the ceiling. ‘It’s not nice, but we’ve been in situations like this before. Worse situations; think about the last one, that poor kid.’

‘I’ll never forget that,’ the DCI countered, sharply, then continued with barely a pause, ‘but . . . Sauce, man, are you a media-free zone? Don’t you know who this is?’

The sergeant shrugged. ‘Not for certain, but I’m assuming she’s the occupant of this apartment.’

‘And her name?’

‘Fonter, the concierge said; Mrs Annette Fonter. At least that’s what I think he said; after finding her, he was in a hell of a state when I spoke to him, high as a kite. The cleaner he let into the flat was even worse; she was having kittens. The paramedics were talking about taking her to hospital.’

‘I’m sure they were all like you say. But I’m fairly sure of this too: as soon as they get themselves together, one or the other of them will be on the phone to the tabloids. Man, this is going to splash on every Sunday newspaper in the country . . . and beyond. When we came through the living room, did you notice the photographs? Big ones, framed, on the wall?’

The young DS raised a trademark eyebrow. ‘How could I have missed them? A bit showy, I thought.’

‘They meant nothing to you?’

‘No.’

‘Does the name Annette Bordeaux mean anything to you?’

‘Should it?’

‘Jesus!’ Even muffled by a mask, the bark of Arthur Dorward, the head of the forensic investigation team that was hard at work on the crime scene, carried across the room. ‘Even I know that,’ he exclaimed. ‘Annette Bordeaux is a supermodel. Hers is one of the best-known faces on the planet. She’s been on the cover of Vanity Fair, Elle, and most of the other glossy women’s mags. And that’s her, lying there dead, in front of us.’

Haddock looked at the body anew; he leaned over the bed, peering at the dead face, its skin the colour of coffee, but dull, without pallor, looking into the bulging eyes, their whites mottled with the tiny haemorrhages that he had seen before in other asphyxiation victims. As always, he steeled himself, willing himself to remain dispassionate. It was a skill he had been advised to master from his earliest days in CID, advised by the big man himself, his mentor. Just as Bob Skinner had never quite succeeded, neither had he; the little dead girl in the car park, that had been bad. He had held himself together at the scene, but a few hours later, at home with Cheeky, his partner, he had been wrecked.

He closed his eyes, visualising the framed images in the living area of the penthouse, and feeling himself go cold inside as he compared them mentally with the cover of the current issue of Cosmopolitan that Cheeky had left on the coffee table.

‘Oh my!’ he whispered.

‘You get it now?’ Pye said.

He nodded. ‘So, where does the name Fonter come from?’ he asked.

‘From her husband: Paco Fonter. He’s a Spanish footballer, currently playing for Merrytown, through in South Lanarkshire. You’ve heard of them, haven’t you?’

‘Yeah, but football’s not my game.’ The DS paused, as a question formed in his mind. ‘Hold on: how can a Scottish football club afford a foreign player with a supermodel for a wife?’

‘Because of its Russian owner,’ his boss explained. ‘He bought a controlling stake at the end of last year. The club’s his personal project. He’s promised to get it up there alongside Celtic and Rangers, money no object. He bought in a whole raft of foreign players, and hired a top manager, a guy called Chaz Baker.’

‘Now him, I do know. Cheeky and I were guests at an invitation golf event at Archerfield Golf Club. The place was full of football people. He was there too; somebody pointed him out to us.’

‘You ask Cheeky who Annette Bordeaux is. She’ll know for sure.’ Belatedly, Pye frowned at his sergeant, as an obvious thought reached to him. ‘How did you two, a polis and an accountant, get invited to a gig like that?’

The young detective flushed slightly. ‘Through Cheeky’s grandpa. The invite was his originally, but his new wife’s not interested in golf. So, seeing as he and Cheeky both have the same name, Cameron McCullough, and he knows I play, he passed it on. The organiser didn’t mind.’

‘From everything they say about your partner’s grandfather, I imagine the organiser knew better than to mind. I thought you kept Grandpa McCullough at arm’s length,’ he added.

‘I do,’ Haddock retorted, quickly. ‘I’ve never met the man, not face to face. Cheeky understands that cops can’t associate with gangsters, alleged or otherwise. She’s never put pressure on me about it.’

‘And when you get married? Will he be absent from the wedding?’

Sauce winked. ‘Everybody will. We’ve agreed that if we ever do, it’ll be in Vegas.’

‘But what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas,’ a female voice pointed out, breaking into their conversation, in a soft New England drawl.

Both detectives turned to face her as she stood in the doorway. ‘Then maybe we will too,’ Haddock countered. ‘It’s a damn sight warmer than Edinburgh in September. Good morning, Professor. You’re looking . . .’

Sarah Grace smiled at his hesitation. ‘Pregnant, Sergeant; I’m looking pregnant. They say that one size fits all with these crime scene clothes, but I feel as if I’m about to prove them wrong. Are your people finished in here?’ she asked, switching into a brisk businesslike tone.

‘The video guy’s done,’ Pye replied. ‘As usual we’re still waiting for the forensic team to finish up. I preferred it when they were our people rather than a central service.’

‘I’m not one of your people,’ she pointed out, ‘so why should they be? Move back, please; let me have a look at her.’

The pathologist stepped up to the hotel-sized bed on which the body lay, crosswise. Annette Bordeaux had died in her underwear, simple black bra and pants. Her face and upper torso were smeared with blood from her battered, misshapen nose, and a brown leather belt encircled her neck, with the end pulled through its silver buckle. It hung loose but her neck bore a vicious, collar-like mark.

‘It took a lot of force to do that,’ Grace murmured. She reached down to the battered face, feeling the nose. ‘Broken,’ she confirmed.

‘Knocked out then strangled?’ the DCI queried.

‘Hit, certainly, and hit hard, but would she have been rendered unconscious? I doubt that.’

‘She could have been doing cocaine,’ Haddock volunteered.

Grace looked up at him, quizzically. ‘Not really relevant, but what makes you say that?’

‘The CSIs found what could be the leavings of a line in the bathroom, in a crevice between two tiles.’

‘Point one,’ she asked, ‘how do you know it’s coke? Point two, how can you tell that she was snorting it? Look at the blood smears on her face. It all came from her nose, but I can see no traces of powder there.’ She frowned. ‘But let’s not speculate, boys,’ she said, as she turned the dead woman on her side and pulled down her pants.

Pye winced as she took the rectal temperature; Haddock looked away.

‘Time of death?’ the chief inspector asked quietly, when she was finished and had checked the thermometer.

‘Not a precise science, as you know, Sammy, but . . . This room has a maintained temperature of twenty-one degrees Celsius, according to the dial by the door. Then I have to factor in her size. She was a slim, fit woman, and given her profession, her body fat index would be pretty low.’

‘You know who she is?’ Haddock exclaimed.

She stared at him. ‘Are you kidding? There was a feature on Annette Bordeaux in the Sunday Herald a couple of weeks ago. The photography was done in this very apartment.’

‘I must get out more,’ the DS muttered.

‘The long and the short of it is,’ she continued, glancing at her watch, which showed two minutes before midday, ‘applying the conditions here to the rate of cooling, and the fact that rigor mortis is still established, I’d say she’s been dead for not less than sixteen hours and not more than twenty. She was killed between four and eight p.m. yesterday.’

Haddock looked at Pye. ‘Do we go get the husband?’

The DCI shook his head. ‘He’s got an alibi. I can think of at least one good reliable witness who’ll testify to it.’

‘Who’s that?’

‘Me. Between eight and ten last night Paco Fonter was playing for Spain in Valencia in a friendly against Argentina. It was on Sky Sports. He scored in the first ten minutes then went off injured.’ He frowned. ‘They have another match next Tuesday, but he’ll be missing it now. Sauce, get on to Chaz Baker. Tell him what’s happened and ask him how we get word to Fonter. While you’re doing that, I’ll call the deputy chief.’

‘You may have a problem there,’ Sarah Grace observed. ‘Mario McGuire and his family left for Italy on Thursday, to visit his mother. I know, ’cos Bob and I invited them to dinner tonight.’ She patted her bump. ‘My last chance for a while to be a hostess.’

‘Then there’s nothing for it,’ Pye sighed, ‘but to break into the chief constable’s Saturday morning. Wish me luck.’

Two

‘Johnny,’ Bob Skinner said, patiently, ‘you might be my cousin, but I’m not a cop any more, and even if I was, that wouldn’t cut you any slack with the prosecutors, not in this case.’

The squat little man looked up from his seat at the conference table in the office of Alexis Skinner, Solicitor Advocate . . . as the still-shiny sign outside proclaimed. His heavy black eyebrows were hunched, like his massive shoulders.

‘You cannae just make it go away?’ he challenged.

‘Not a prayer. You put the guy in Wishaw General Hospital.’

‘Aye but . . .’

‘No “buts”. You split your kitchen table across the man’s back; you broke three of his ribs and cracked two vertebrae.’ He picked up a photograph from an open folder. ‘Look at the bruising on him.’

The flicker of a grin twisted his cousin’s mouth and his eyes twinkled. ‘It was a big oak table,’ he murmured.

‘Then maybe you should just have hit him with a chair!’ Skinner laughed, in spite of himself.

Johnny Fleming shook his head. ‘Naw, they’re pretty solid too. Bob, what would you have done? Suppose you’d walked in on him swingin’ a milk can at Alex here, like Barney McGlashan did tae our Gretta.’

‘I’d have restrained him and called the police.’ Skinner winked at his daughter. ‘That’s if Alex hadn’t kicked the legs out from under him first.’

‘Oor Gretta’s a sturdy wumman,’ his cousin sighed, ‘but she’s sixty-two. We did call the police, and look what happened. I’ve been charged and McGlashan hasnae.’

‘Because he didn’t actually hit her,’ Alex intervened. ‘And,’ she added, ‘there’s no corroborated evidence that he meant to do so. It’s his word against Gretta’s, for you came in halfway through their argument.’

‘What’s to do, then?’ Fleming asked her.

‘I recommend that you plead guilty,’ she told him, firmly. ‘We do not want this thing to go to trial. The fiscal will have his say, but he has no reason to press for a custodial sentence. McGlashan has previous for violence, and you don’t. I’ll enter a plea in mitigation, claiming an unprovoked lunge at your sister, and I’ll try to persuade the sheriff that you acted instinctively against what you saw as a real threat.’

‘Will he buy that?’

‘I hope so. Yes,’ she decided, ‘I expect so. I’ve never appeared at Lanark Sheriff Court, but I haven’t heard any stories about the sheriff there being a hardliner. There will be a fine, and you might even be ordered to pay some victim compensation, but . . .’

‘I’m no’ havin’ that,’ Johnny protested. ‘Pay compensation to yon animal?’

‘Oh yes you are,’ Alex snapped. ‘You will nod politely at whatever the sheriff says. You’ll utter one word and that will be “Guilty”. Understood?’

‘If you say so.’ He looked up at her. ‘Was she aye this bossy, Bob?’

‘Pretty much,’ Skinner replied, cheerfully. He spoke the truth. He had brought his daughter up alone from the age of four, after her mother had died in a mangled car. While she had never been a rebel, she had staked out her own territory from a fairly early stage. He felt a weird kind of pride as he recalled her, aged five, looking him straight in the eye, after he had answered ‘No’ to her plea that they watch a video that he had seen so often he had it memorised, and saying, ‘Why not?’ He had been stumped for an answer, and he had watched Dougal and the Blue Cat for the tenth time . . . or was it the twentieth?

‘I’d better do what she says then.’ Fleming stood. ‘What happens next?’ he asked.

‘I’ll advise the fiscal that I’m acting for you,’ she told him, ‘and I’ll ask for an early pleading diet. I’ll let you know when we have a date for court.’

‘Good. Can I go now? I have to get back to the farm. I’m covering McGlashan’s work till I get a new labourer in to replace him.’

‘Did you dismiss him formally?’

‘No.’ He stared at her. ‘You don’t think he’d come back, do ye?’

‘No,’ she said, ‘but you can bet your boots that he’ll be on to a personal injury lawyer as soon as he’s discharged from hospital. If you agree, I’ll write to him advising that his employment has been terminated without notice on grounds of gross misconduct.’

He nodded. ‘Do it. I’ll tell Gretta tae call you wi’ his address. Do ye think he’d have the nerve to sue me?’

‘Bet on it. But we won’t roll over. We’ll threaten a counter-suit by Gretta for emotional distress, and by you for the things he smashed in the kitchen during the argument.’

Cousin Johnny looked at her, smiling. ‘You know what?’ he chuckled, as he headed for the door. ‘You’re a Fleming, right enough. I’m beginning to feel sorry for that bastard.’

Alex stared after him. ‘What the hell did he mean by that?’ she exclaimed once he had gone. ‘I’m a Skinner, pure and simple.’ She turned and stalked off towards her office.

‘No,’ her father said, following in her wake, ‘you’re more than that. You’re the sum total of everything that made you. There are some pretty powerful ingredients in your genetic soup; not just from me but from your mother. The Grahams, her branch of the family, included an African missionary, a contemporary of David Livingstone, who was killed by a hippo before he could convert a single native, a soldier who died beside General Gordon at Khartoum, and a woman who was imprisoned for life for smothering her child.’

She dropped into her chair, frowning. ‘Jesus, Pops,’ she murmured, ‘I’m past thirty years old and you’re telling me all this now?’

As he took the seat facing her, Bob Skinner was aware, not for the first time, of his failings as a parent. ‘I thought your Aunt Jean had fed you all your family history,’ he protested, weakly.

‘She did mention something once about Duncan Graham, the missionary. I must have been ten; I was researching Livingstone and Stanley for a primary school project and I asked her about Livingstone, since his museum’s near where she lives. She never said what had happened to him, though, and she never said a word about the other two ancestors.’

‘She probably wanted to spare you the gory parts. William Graham, the soldier, was hacked to pieces, literally, and as for Margaret Graham . . . well, most families would bury a story like that.’

‘But what about your side?’ she asked. ‘You’ve never talked about your family. I remember Grandpa Skinner, of course. He was nice and he was kind, and he was always a soft touch for extra pocket money, but he never told me things, like what you were like when you were growing up, or what my grandma was like.’

‘Your Grandma Skinner was an alcoholic,’ he retorted, a little too sharply perhaps, but memories of his mother were still painful to Skinner. ‘As for my childhood, Dad knew sod all about that, for he was never home. If he never spoke about it at all, that may have been because he didn’t want to talk about Michael.’

‘My uncle? The one who died?’ She frowned, slightly. ‘He was a drunk too, wasn’t he?’

Bob nodded. ‘He was a drunk, he was a sadist and he was a coward. He was almost ten years older than me, and he bullied me all the time I was growing up.’

The frown deepened; it became a look of pain.

‘Pops,’ she murmured, ‘you never . . .’

‘Told you about it? Of course not. Why share stuff like that with you?’

‘And Grandpa never knew?’

‘No, he never had a clue; as for Mum, she was half-pissed all the time and Michael was her blue-eyed boy.’

‘How did you stop it?’ Alex asked.

‘I grew up,’ he replied. ‘I became what I am; by the time I was about fifteen, even then I was strong enough to put the fear of God into him. I never complained to my father though. I dealt with it myself when I was ready. Not long after that Michael lost it completely, and was institutionalised.’

‘And I grew up,’ she reminded him, quietly, ‘with an uncle I knew nothing about.’

‘Sorry,’ he murmured sheepishly.

‘A man who was locked away without trial, from what you’re saying.’ There was anger in her tone, at a perceived injustice.

Skinner had to check himself; he had never flared up at his daughter, not once in her life, but he came close then. ‘You’re talking like a defence lawyer,’ he said, curtly. ‘Trust me, if you knew the full story you’d want to prosecute.’

His reaction took her by surprise; she backed off. ‘Okay,’ she exclaimed, ‘if that’s how you feel, it’s my turn to be sorry. But you must admit,’ she teased him, ‘you’ve been neglectful as a parent. You mentioned my genetic soup earlier . . . a colourful image, by the way . . . and you’re right, it is my genetic history, so I need to know about it. Not least,’ she added, defusing any tension with a smile, ‘so that when a potential client calls me and tells me we’re cousins, I’m not left babbling like an idiot on the other end of the phone.’

He nodded. ‘Touché,’ he agreed. ‘Right, as for Johnny: your Grandma Skinner was a Fleming, you knew that . . . ?’

‘Yes,’ she agreed, ‘but that’s all I’ve ever been told, and obviously I never had a chance to ask her about it, her being dead before I was born.’

‘You wouldn’t have got much out of her anyway,’ he grumbled. ‘I never did.’

‘Christ, Dad,’ she sighed, ‘you sound bitter.’

He glanced at her, eyes hooded by his heavy eyebrows. ‘Do I?’ he exclaimed. ‘I’m not really; sad, more like it. I can understand now that she had an illness, but you don’t know about these things as a child.’

‘What about your grandparents?’ Alex asked.

‘I was getting to that. Grandpa Fleming died when I was six, but I remember him quite well. He was a tall old geezer, with frizzy white hair. He could be quite severe with my mum . . . now I know why . . . but he was great with me. One day . . . I’d have been five at the time; it was the summer and I was just about to start school . . . he took me on a trip, on the bus from Motherwell up through Wishaw and beyond, heading towards Carluke. We got off at a place called Overtown, and walked till we got to a farmhouse. There was a man there, waiting for us, his cousin. His name was David Fleming, and he was Johnny’s father.’

‘Was Johnny there too?’

‘Yes, but he was working on the farm. He’d have been, what, going on twenty at the time. Uncle David . . . that’s what I called him . . . put me on a tractor and drove me around the fields. It had been a good summer; they were harvesting, early, for the weather was bound to break. I met Johnny, but only briefly; he was busy. To me he was huge; you’ve seen the width of him now, aged sixty-nine, so imagine him approaching his prime. Gretta was there too; she’d have been early teens, a strange, shy lassie with bottle-glass specs. I remember, it was hot but she had on this big thick jumper.’

Alex smiled. ‘What about the kitchen table?’ she asked. ‘Was it there?’

‘I guess so. I can’t say for sure, but from what I can see in the police photographs, that could have been it; it might have been a hundred years old even then, if not more. Anyway, on the tour of the farm, Uncle David drove us up to this big old mansion. He said it was called Waterloo House, and it had belonged to an ancestor of his, that the farm, or most of it, had been its estate. I remember asking him what an ancestor was. He told me it was a relative who’s been dead for a long time. I asked him if he lived in the house now. He laughed and said it was too grand for the likes of him. I discovered much later that it had lain derelict for a while, until Grandpa Fleming inherited it from his grandfather, and turned it into four apartments.’

‘So your Grandpa Fleming,’ Alex exclaimed, ‘my great-grandpa, was actually minted!’

‘No,’ he laughed, ‘because he made hardly any money on the conversion. Waterloo House is a listed building and Historic Scotland, or whatever it was called then, imposed all sorts of conditions.’

‘What did Grandpa Fleming do?’

‘He was a saddler, a leather manufacturer. It was an old family business that had been big at one time, but he inherited it in time to see it through its final years, until he sold the factory on to a competitor for as much as he could get.’

‘Where did it all come from, the farm, the mansion, the factory?’

Skinner smiled. ‘Well,’ he sighed, ‘that’s where it gets interesting. After we had seen all of the farm, looked in the milking sheds and everything, we went into the farmhouse and had our tea, in the sitting room. Grandpa said that Auntie Jessie, Uncle David’s wife, Johnny’s mother, was a famous baker. I have a memory of her in the kitchen, making potato scones; they looked like chapattis before she cut them into quarters.’

‘Was she as good as he said?’ his daughter asked.

‘Haven’t a clue; it was polite to praise your hostess for her baking in those days. And for her jam; jam-making was a big thing with Auntie Jessie’s generation. I’ve no idea how good they were . . . this is way back, remember, around the time England won the World Cup. But I do have one memory of that room, one that stuck with me for years. There was a portrait over the fireplace, of a man in middle age, a strong-looking fella. Grandpa smiled up at the picture, and kind of touched his forelock, in respect.’

‘What was it?’

‘Let me finish,’ he insisted. ‘He’d have been a good-looking bloke, maybe he’d even have looked a bit like me,’ he chuckled, ‘but for one thing. There was a big vertical scar down the left side of his face, and his left eye was grey and sightless. The sight of it scared me a wee bit, aged five, and I never forgot it. Uncle David drove us back to Motherwell, in an enormous bloody Jaguar that had sacks of spuds in the boot, and after he dropped us off I asked Grandpa who the man in the painting was. He said it was a long story, and he’d tell me another time.’

‘But there never was another time, was there,’ Alex guessed. ‘You said he died when you were six?’

He nodded. ‘That’s right; he had a massive stroke the following week and died less than a year later. It was the last day out we ever had, and the only time I ever went to the farmhouse. I’ve seen Johnny a few times since then, always at funerals. His parents’, my mother’s, my dad’s; not at Grandpa Fleming’s though, I was too young to go to that.’

‘That’s strange, because just now it was as if you and he have been close all your lives. When was the last time you saw him?’

‘At my father’s send-off,’ he told her. ‘The time before that was at your mother’s. I didn’t expect Johnny to be there, but he was, him and Gretta, and that moved me.’

‘He never married?’

‘No, and neither did Gretta. He took over the farm and she took over the kitchen. She’ll be the famous baker now, I imagine.’

‘Probably shops in Tesco,’ Alex laughed, mocking his nostalgia.

‘I’ll bet she doesn’t. She’ll be the last of the old-time spinsters. Did you see that pullover Johnny was wearing? I could almost guarantee she knitted that.’

‘Typical man,’ she snorted, ‘you view women as stereotypes. You haven’t seen Gretta in a quarter of a century, and you’ve put her in a box. She’s probably a part-time yoga teacher and drinks Bellinis.’

‘Trust me on this,’ Bob insisted. ‘I’m a Lanarkshire boy and they’re an old-time Upper Ward family.’

‘That’s gobbledegook to me. What about the man in the portrait? Get on with it, Father, I’m busy, unlike you.’

She had a point, and he knew it.

Since leaving the police force when his last post as Strathclyde chief constable disappeared into what he saw as the capacious maw of the new unified Scottish National Police, he had been struggling to balance his life. That was not to say that he had been inactive. He had been involved in a couple of what he chose to best describe as ‘consultancy situations’.

The first had led to him becoming a part-time executive director of InterMedia, a Spanish media group, owned by his friend Xavi Aislado and his ancient brother Joe. The company’s flagship titles included the Saltire, a newspaper rescued from obscurity largely by Xavi’s work as a young journalist and then from insolvency by his family firm.

The second had ended unfortunately for the person who commissioned him. As Skinner had explained to him afterwards, ‘You can buy my time, but you can’t buy my integrity.’

He had also been appointed to the board of the Security Industry Authority, a post he had accepted, without any enthusiasm, to please a friend, Amanda Dennis. He had done so on the basis that he saw it as better to please the head of MI5 than to piss her off.

He found that he enjoyed the media job a lot and gave it more time than the contracted one day a week, but in contrast the SIA post was deadly dull, involving the absorption of reams of submissions that stated the obvious, then rubber-stamping them at monthly meetings in London. After only a few months, he knew with certainty that when his three-year term of office expired, he would not seek renewal . . . if he could stand it that long.

Apart from that, though, he had time on his hands. The phone had rung, the non-executive directorships had been offered, and had been turned down, all of them, because their common thread was the fact that every one of the offering businesses was only interested in what his name and reputation would add to their bottom line, not in any new skills that he might bring to the table.

He had told the last one in no uncertain terms that he had no interest in endorsing the security of their double-glazed doors and windows, when he knew half a dozen ways of opening them without tripping even the most sophisticated alarm system.

Some of that time he had given to Alex. She had walked away from a very promising and very lucrative career in corporate law, and struck out on her own as a solicitor advocate, specialising in criminal defence work. He had done a few small investigations for her, but most of his usefulness had been as a sounding board, advising her on the odds for or against an acquittal.

Basically, he had been telling her when she should defend and when she should attack. That was why she had consulted him about Johnny Fleming; that and her curiosity about the family connection.

Six months before, his situation would have worried him, as he had been a serial workaholic, but his life had changed in more than professional terms.

Sarah Grace, his ex-wife, but partner once again, and he were expecting a late and wholly unplanned addition to their family. Alongside that he had another situation with his oldest son, from another relationship. He was in jail, and would be until the end of the year.

‘Okay,’ he said, briskly, to his firstborn child, ‘I’ll keep it brief. That portrait, the one in Uncle David’s sitting room: the image burned itself into my head. I asked my mother about it once, when I was nine, but she must have been in a haze at the time for she brushed me off.

‘After that,’ he continued, ‘life intervened. I had my troubles with my brother, then when they were sorted I met your mother, went to university, graduated, joined the police . . . disappointing my father by rejecting his l

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...