- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Former Chief Constable Bob Skinner may have left the police service, but he's never far from a case. When his old mentor on the force, Jimmy Proud, finds himself in a desperate situation, Skinner gets pulled into a murder investigation that's been closed for 30 years. The Body in the Quarry case was well-known around Edinburgh at the time: a popular priest found dead in a frozen quarry; a suspect with a clear motive charged; a guilty verdict. But with a journalist uncovering new evidence, the cold case has come back to haunt Proud – and only Skinner can help him.

Release date: November 15, 2018

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 292

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

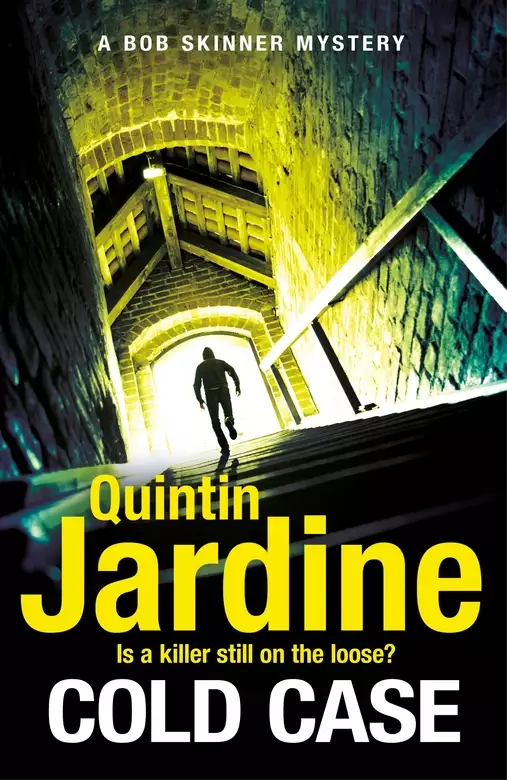

Cold Case

Quintin Jardine

‘Bob, I’m wondering if you have some time free tonight. The thing is . . . I’ve got a problem.’

I have one thing in common with Maggie Thatcher: history showed her to be a long way short of being St Francis of Assisi, and so am I. I’ve never been much good at sowing love to replace hatred, and when it comes to bringing joy to drive away sadness, my record is patchy to say the least. However, since I walked away from the police service and Chief Constable Robert Morgan Skinner became plain Bob to all and sundry, I have noticed that when my friends have a problem, they may choose to come to me for help and counsel.

I’ve had to deal with a few difficult situations, for my friends tend to be the sort of people who draw problems like tourists draw midgies on a damp and wind-free lochside morning. But if there was one I never expected to make such a request, it was my predecessor in the Edinburgh chief’s job, and my principal supporter for much of my career, Sir James Proud.

The thousands who served under his command used to call him Proud Jimmy, a silly nickname I will use only once in this account, to emphasise how inappropriate it was. If anyone ever belied his name it was Sir James. I have never met a man in a command situation who exuded such humility, and who showed less self-importance or pride. The phrase ‘public servant’ is bandied around at will, but I’ve never known anyone who grasped its true meaning, and put it into practice, as well as he did.

Jimmy at work was one of those rare people who didn’t have problems. He had challenges, and it’s a tribute to him, and a reason for his longevity in a job that wore me out in a few years, that he rose to all of them. I’ve known officers who went into his office to be disciplined and were heard to thank him as they left for the wisdom he had shown them. Latterly, of course, he didn’t do too much of that; he delegated it to me. No one who wound up on my carpet ever left feeling better for the experience.

That was why, when I took his call that day, as I was ending a meeting in the Balmoral Hotel, my instant reaction was apprehension. A few months before, he had been diagnosed with testicular cancer, but the last medical bulletin he had passed on to me had been positive. His therapy had been effective and he was officially in remission. It’s back, was my first thought, even though he had just told me he was clear.

‘Jimmy . . .’ I murmured.

‘No, no, no!’ he insisted. He always could read my mind. ‘It’s not that. That’s fine; I meant it when I said I’m in recovery. I saw my oncologist yesterday and she said I’m in better shape than she is. She’s right, too. Poor bugger’s a stick-thin midget; I wouldn’t be surprised if she’s her own patient pretty soon. No, son, this is something else entirely, something completely out of the blue.’

‘Something that’s worrying you,’ I observed, ‘from your tone of voice.’

‘I confess that it is, son,’ he sighed. ‘Maybe there’s nothing to be done about it. If so, I hope the judge takes pity on me. But if there is anyone that can help,’ he added, ‘I’m talking to him right now.’

‘Jesus Christ, Jimmy!’ I had visions of my old boss being caught slipping out of the grocer’s with a filched tin of corned beef in his pocket. He had never shown the slightest sign of dementia, but he was in the age bracket where it’s most likely to occur; indeed, the variability of Lady Proud’s memory had been worrying Sarah and me of late.

‘He’s involved, in a way,’ he said. ‘I might need a miracle. This is serious, Bob: the last thing I need at my time of life.’

‘Okay,’ I told him, ‘we can meet tonight. Do you want to come to me or me to you?’

‘Neither. I don’t want either of us to have to explain anything to our wives. I’ll meet you in Yellowcraigs car park, eight o’clock, if that’s all right. I’ll be taking Bowser for a walk.’

‘It’s all right, but why don’t we meet on Gullane Bents? Why Yellowcraigs?’

‘Because nobody can see it from your house.’

Two

I thought about Jimmy all the way home on the bus.

Me? Bob Skinner? Bus?

That’s right. It had been the simplest way to get to the Balmoral given the institutionally baffling and constantly changing traffic management in the heart of the city of Edinburgh. Yes, I could have driven by a simpler route to my office in Fountainbridge and taken a taxi, but I had nothing else to do that day, so I let East Coast Buses take me straight to the door.

I was slightly vexed by my new engagement, because I had been looking forward to spending some time with my younger kids in the evening, once the homework burden had been disposed of – don’t get me started on that: I don’t believe in it – and then a quiet dinner with Sarah, my wife, in celebration of the successful conclusion of an investigation in which I’d become involved.

When I left the police service, or when it left me, as I prefer to put it, I had no clear idea, not even the vaguest notion, of what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I’m still not certain, beyond my determination to see all of my children through to happy adulthood. I have six of those: the eldest by far is Alexis, my daughter with my late first wife Myra. She has turned thirty and is building a reputation as the Killer Queen of Scottish criminal defence lawyers, after turning her back on the lucrative but unfulfilling corporate sector. Mark, he’s in his teens; we adopted him after he was orphaned by separate tragedies. James Andrew, the first of my three with Sarah, is a hulking lad who is easing his way through primary school, just as his sister Seonaid is starting to make her presence felt there. The youngest, Dawn, was a complete and total surprise, and is still only a few months old.

And then there’s Ignacio, the son I didn’t know I had, the product of a one-night stand twenty years ago with a dangerous lady named Mia Watson, who left town a couple of days after he was conceived and didn’t reappear until very recently, still in trouble and still dangerous.

Ignacio lives with me now, and is embarking on a degree course at Edinburgh University; he’s a very talented chemist – too talented, with a couple of things on his teenage CV that will never become public. His mother has found a safe haven – I will qualify that; it’s been safe so far – having married a guy from Tayside called Cameron McCullough, known as ‘Grandpa’ to his associates and on his extensive police file, although only his granddaughter gets to call him that to his face. My side had him marked down as the biggest hoodlum in Scotland, but we never laid a glove on him. He always pleaded innocence, as he still does, and was never convicted of anything; indeed, he was only in the dock once, but that case collapsed when the witnesses and the evidence disappeared, traceless. There is an irony in him being my son’s stepfather, one that isn’t lost on either of us, or I’m sure on any of the few people who are aware of it.

I didn’t think of Grandpa, though, as the X5 bus bore me homewards to Gullane. My mind was too full of Jimmy’s mysterious call and what might lie behind it. It wasn’t the first of its type I’d had since I’d become a private citizen, and quite a few of those had been the triggers for some accursedly interesting times.

Have I ever doubted my early termination of my police career? In a word, yes, but just the once. The first time I had to drive myself from Gullane to Glasgow, through the dense motorway traffic, I found myself looking back nostalgically on the times when I’d made the same journey in the back of a police car, with my driver in front. He never flashed the blue light; he didn’t have to: one glimpse of it in a trucker’s rear-view mirror and he vacated the outside lane, sharpish.

That was the only time I ever regretted my decision to turn my back on the controversial national police service that I’d always opposed but had been unable to prevent, even though I was married at the time to one of the few politicians who might have stopped it. I’m not saying that was the reason why Aileen de Marco and I split; it didn’t help, but we were pretty much doomed from the outset, by the lingering occasional presence of a famous Scottish movie actor, and by the fact that I’d never really fallen out of love with Sarah, Aileen’s predecessor.

I knew at the time that I was right about police unification, and I still know that I am, although I take no pleasure from the obvious truth that a great majority of Scots now agree with me, both serving cops and civilians.

There’s nothing I can do about it, though; only the politicians who caused the fuck-up can repair it, and there’s very little chance that they will. However, I am content. I still have, as an old guy in Motherwell used to say, my feet in the sawdust.

I don’t call myself a private detective, but I do accept private commissions from individuals. Also, recently, I have been called in by an old colleague and friend in London to help with a couple of situations. As a result, I now carry a piece of plastic that gives me Security Service credentials; that’s MI5 to most people. Nobody outside my inner circle knows about my involvement, that being the nature of the beast. At the moment I’m inactive on that front, but Amanda Dennis, the director general, could ask for my help at any moment.

All that occasional activity sits comfortably alongside what’s become my main employment in my second career, my part-time executive directorship of a Spanish-owned company called InterMedia, which operates internationally. Amongst a long list of media outlets, newspapers, radio and TV across Spain and Italy, it’s also the proprietor of the Saltire, an old-established Edinburgh newspaper that was hirpling towards the press room of history until its star reporter, Xavi Aislado, persuaded his brother to buy it, transformed it and made it the only title I know of that is still maintaining the circulation figures of its printed version. Not only that, he is spreading the readership of the online edition across the English-speaking world, and increasingly into Hispanic territory, for we are translated. Hector Sureda, our digital guru, told our last board meeting that the Saltire now has as many Spanish-speaking subscribers in the USA as it has Anglos. Globally, the main Spanish title, GironaDia, does better, but we’re catching up fast.

I got off the bus in Gullane just as the school crossing patrol woman was seeing James Andrew and Seonaid across the road. Jazz – he’s never quite shaken that nickname – does not like that too much; having the traffic stopped for him by a lollipop lady is beneath his dignity, he feels, but I have told him firmly that looking after his sister is a responsibility I entrust to him and that he will do what it takes to fulfil it.

I could see them from my bus stop in the distance, and waited for them. As I stood there, Sir James Proud walked past me, a newspaper under his left arm and a Co-op shopping bag in his right hand.

‘Afternoon, Bob,’ he said briskly, with the briefest of glances in my direction, then passed me by without breaking his stride.

Three

I pushed the mystery to the back of my mind for a few hours, devoting them to Sarah and the kids as I had planned. Dawn was teething and had given her mum, and Trish, the children’s carer, a tough day, but I have experience in such matters, and some skill; pretty soon she was back to her placid best. Smug, Skinner, smug.

I’d hoped to spend some time with Ignacio too, but he called from university to say that he needed to work late on a class end-of-session project and would be staying at Alex’s overnight. I didn’t mind that; he and his half-sister had bonded from the moment he appeared in our lives. My kid, as Alex has always been to me, is always great with the second family – she is James Andrew’s idol – but she liked having a sibling with whom she could speak as an adult. Ignacio, he just liked having a sibling, period.

A set routine is important for all children – when Alex was growing up, it was just the two of us, and that was difficult – but bedtime is a fluid affair in our house; homework is done after supper, and then they have some free time until it’s lights out. For Seonaid, that’s seven o’clock, for James Andrew it’s eight, although often he crashes early. Mark is old enough to set his own limits now, but he’s usually asleep by ten thirty.

Jazz had just disappeared upstairs with a mug of hot chocolate when I told Sarah I was going out for a while.

‘Where you off to?’ she asked.

I grinned. ‘I’m going to see a man about a dog.’

She raised an eyebrow, but said nothing. She assumed, I assumed, that I was going to the golf club or to the pub. I imagined her raising the other eyebrow a few seconds later when she heard me start the car.

Yellowcraigs Beach lies just outside Dirleton, the neighbouring village to Gullane; it’s also called Broad Sands Bay on some maps, but not many people know that. It’s a favourite spot of James Andrew and Seonaid, not so much for the sands, more for the children’s play park. It has a pirate ship theme, a reference to Fidra, the small island which is situated not far below the low-tide mark. Legend has it that Robert Louis Stevenson, a frequent visitor, drew inspiration from it in writing Treasure Island, which is in my eyes the greatest adventure story ever written in the English language.

Mark would go there too on occasion, but with less enthusiasm. The boy is a natural mathematician, with computer skills that I come nowhere near to understanding, but he doesn’t know his left hand from his right, nor does he have any interest in finding out which is which. The climbing frames and rope roundabouts in the playground never offered a challenge to him, only a hazard to be avoided.

That’s where Jimmy took me. He was waiting for me when I reached the car park, a couple of minutes after eight; Bowser, his springer spaniel, was still on its lead, tugging. Both of them looked impatient. The light of day was dying, but its warmth lingered. I’ve known many years when the Scottish summer has been over by the middle of May; I wondered if this would be another.

‘Sorry,’ I said as I climbed out of Sarah’s new car, a big Renault hybrid. She chose it because it has seven seats, a sign of the family times. ‘I got caught behind a cycling club,’ I added, by way of an excuse.

‘No matter,’ he grunted. He glanced around. We weren’t alone. Yellowcraigs is a popular dog-walker destination in an area where pooches seem to outnumber pigeons. I’ve never had a dog, but Seonaid is beginning to drop hints about puppies. Since she’s known how to push my buttons since she was a year old, I suspected that the household would soon hear the patter of tiny paws.

Sir James gave Bowser a quick tug. ‘Come this way,’ he said, to the dog and to me. ‘There are no kids around at this time of the evening, so it’ll be private through here.’

I followed him out of the car park, across the road and down the short tree-lined path that led to the Treasure Island mock-up. Last time I’d been there, four days earlier, I’d watched Jazz climb to the top of the rigging surrounding the tall pole that represented a mainmast, while Sarah called after him to be careful. I don’t think he’ll ever be that, but I don’t worry as she does, because he’s strong, agile and he knows his limits, as did I when I was his age. However, I do worry about his determination to join the military when he grows up. I don’t like the idea of any of mine in harm’s way.

I took a seat on a long, snake-like swing as Jimmy unclipped Bowser’s lead. The spaniel shook itself, then found its way through the rigging and lifted its leg against the Hispaniola’s mast. ‘Piss on you, Long John,’ I whispered, then looked up at my friend.

His silver hair was thinner after his course of chemotherapy, and he had lost some weight, but physically he looked okay. His expression suggested otherwise.

‘So, Jimmy,’ I exclaimed, breaking the silence. ‘What precisely the fuck is all this about?’

I must have sounded exasperated, for his immediate reaction was to whistle for his dog and snap his fingers. ‘Here, Bowser!’ he called out, fiddling with the clip of the lead. ‘I’m sorry, Bob, this is a mistake. I have no right to put this on you. You’ve got enough on your plate with the newspaper, the family and everything else in your life. It was thoughtless of me to call you.’

I glanced across at the simulation of the Hispaniola, where Bowser was ignoring his master and having a real good sniff.

‘Bollocks to that,’ I retorted. ‘You’ve looked out for me more often than I care to recall. If you’ve got a problem and you took it to anyone else, I’d be seriously, seriously pissed off. So come on, man, out with it.’

He seemed to sag, and lowered himself onto the circular perimeter of the enclosure, wincing as he settled on to it. He’d had surgery as well as the therapy.

For the first time since we’d come together, he looked me in the eye. ‘Does the name Matthew Ampersand mean anything to you?’ he asked.

I did a quick trawl through my memory; I can’t claim to recall every investigation during my career, but most of them left a mark. ‘I can’t say that it does,’ I admitted when I was done. ‘Professional?’

‘Yes, but this business happened before you joined the force. I thought you might have remembered the name from the newspapers of the time, but no matter. He was a murder victim whose body was found in the old quarry at Traprain Law, here in East Lothian, on a Wednesday three weeks before Christmas. It had been freezing hard for days, otherwise he’d have gone to the bottom of the quarry pond, but the ice was so thick he didn’t go through it, just landed on it very hard. At first they thought he was a suicide, but Joe Hutchinson, the pathologist, found injuries that were inconsistent with him having jumped.’

At the back of my mind, something stirred. A vague recollection of headlines about ‘The Body in the Quarry’ around the time I was completing my university degree. ‘Yes, maybe I do recall it,’ I murmured. ‘Why? Has he come back to haunt you?’

‘You could say that,’ he snorted. ‘I’m being accused of killing him.’

Four

I stared at him, gasped, and then laughed.

‘Are we on Candid Camera here?’ I asked.

‘I wish we were,’ he said. ‘It’s the truth.’

‘Come on,’ I protested. ‘You were a police officer for forty years but you never as much as kicked a hooligan’s arse in all that time. You’re the least violent man I know. Tell me who’s saying otherwise, and I’ll put them right in a way they won’t forget.’

‘It’s a journalist.’ Bowser had rejoined us; he was giving me a funny look, as if he had detected his owner’s distress and blamed me for it. Jimmy may have sensed this too, for he reached out and ruffled the dog’s ears. ‘He’s called Austin Brass. Ever heard of him?’

I recognised the name at once. The guy wasn’t what I would call a journalist, but the world is changing and most of its definitions are being rewritten. He ran a blog, a website called Brass Rubbings; its focus was on the police, but not in a positive way. Its meat was misconduct, and it offered a ready ear to anyone with a complaint, however far-fetched, however bizarre.

During my brief time as chief constable of Strathclyde, before the post became part of Scotland’s history, my media people had been kept busy by his pursuit of an allegation by a group of citizens in Argyllshire that their local officers tended to prioritise along ethnic lines, with long-established families being given preferential treatment over incomers, moneyed folk who’d moved out of southern cities in search of a calmer lifestyle, ‘white settlers’ as they were labelled in those parts. I sent a trusted officer up there straight away; she reported back, very quickly, that the complaint was valid. Her investigation mirrored the journalist’s own. The guy was thorough; he had done his homework before coming to us and he knew that his story was well founded. Action was taken, Brass was advised, and his site had a field day. Fortunately for my force, the damage was limited, since the mainstream media were not over-keen on promoting an upstart rival by picking up on his story.

‘Yes,’ I told Jimmy.

‘Do you know much about him?’

I nodded. ‘Some.’ I didn’t want to go into detail about my Strathclyde experience. ‘He’s not to be taken lightly,’ I admitted. ‘What’s he saying?’

‘Best if I start from the beginning,’ he said. ‘As I told you, when Ampersand was found, it was assumed that he’d jumped, so nobody got excited. Then Joe announced his findings and everything changed. What had been an inside-page story about the sad death of a popular priest—’

‘Priest?’ I repeated.

‘Yes, he was an Episcopalian minister. As soon as the murder inquiry was set up, it became front-page news, nationally. The press went crazy and we were under pressure from the off. Sir George Hume, the chief constable of the day, only liked to be seen announcing good news, but he couldn’t duck that one. He did a media briefing where he announced that “Scotland’s top crime-fighter” – he actually used that phrase – would be heading the investigation. That, of course, was Alf Stein, your old mentor. He was a detective super at the time, but Sir George was smart enough to know that the then head of CID, an over-promoted old school pal of his from Daniel Stewart’s College, whose name was Rodney Melville, could not find his arse with both hands and a map.’

I smiled at the mention of the name. ‘Alf told me about him,’ I murmured. ‘He wasn’t as kind as you, though.’

Jimmy grunted. ‘No, he wouldn’t have been; he never could stand him. Up until then Alf had only a local reputation, given that Edinburgh didn’t have a lot of high-profile crime. He was competent, down-to-earth and popular, and that suited him fine. But as soon as Sir George stuck that label on him before the assembled media, he became a national figure, with huge expectations lumped on him.’

‘I’d certainly heard of him before I joined the force,’ I admitted, ‘but I’d no idea that was why.’

My old boss nodded. ‘Oh yes, that was the reason,’ he confirmed, ‘for he lived up to Sir George’s star billing. He made an arrest within a week, and saw it all the way through to a conviction. The fact is that Alf only had two high-profile murder cases in his whole career – and you were part of the team on one of them.’

He didn’t have to remind me of the details; I knew well enough. It was a double murder, a businessman and his wife; he was kidnapped and she was held hostage to force the guy to give the gang access to his factory. When they had what they wanted, the captives were killed. It went unsolved for years, and when finally the killers were identified, there had been nobody to arrest, for two of the principals died in a suicide pact, and the third had been seen last heading into the Australian outback without food or water.

As the senior investigating officer, ‘Scotland’s top crime-fighter’ was given all the credit by the media, and it became part of his legend, but the truth was we did nothing to close the case. The answer was brought to us by someone else, a guy who turned out to be almost as big a loser as the two victims, in a different way. Jimmy didn’t know that, though, and it wasn’t the time to enlighten him.

‘How did the Ampersand thing pan out?’ I asked him.

‘There was an obvious suspect from the start. His name was Barley Meads and he and his family had been members of Ampersand’s congregation, until there was a big falling-out. That family included a teenage daughter, name of Briony; she was an active member, went to bible class and sang in the church choir. She spent a lot of time at the church, eventually too much time for her father’s liking. He followed her there one night and, he claimed, saw the vicar and his kid in what he described as “a compromising position”. Briony was fifteen at the time; Ampersand was forty-two. Barley reported him to us, but there was no corroborating evidence of any kind, and the daughter refused to confirm his story.’

‘Was the vicar interviewed?’

‘Naturally he was, by a uniformed sergeant. He denied it absolutely; he said that whatever Meads thought he’d seen, there had been no inappropriate behaviour. He said that Briony had helped him off with his dog collar once when it had got stuck, one evening when the lass was in the church practising her solo for the following Sunday, and suggested that maybe Barley had seen that and got the wrong idea. Without an admission from the girl, or a complaint by her, there was nothing for us to do but dismiss Meads’s allegation. He took it badly, I can tell you,’ he said with a grimace.

His sudden vehemence surprised me. ‘How do you know?’

He gazed back at me. ‘It was me that dismissed it. I was a chief inspector then, out in Dalkeith, and it landed on my desk for review. I sympathised with the man, for I felt that he really believed what he was saying, but I didn’t have any choice. Like I said, he didn’t take it well. He was a big, brawny fellow, a farmer; he yelled at me, and for a minute I thought I was going to have to call for assistance, but it didn’t go that far. He swore that he wasn’t giving up and that Ampersand would get what was coming to him.’

‘Did you warn him against approaching Ampersand?’

‘Of course I did, man,’ Jimmy snapped tetchily. ‘He replied that he had no intention of doing that but that he still intended to ruin the man, to put an end to his career. He tried too, using a different channel. He made a formal complaint to the bishop who was the titular head of the Scottish Episcopal Church. Meads didn’t stop there. He took it to the press as well; his idea was that the adverse publicity would be enough to have the man kicked out of the charge, but it didn’t work out that way. Briony being fifteen, the papers were constrained in what they could report. They couldn’t use her name because of the nature of the allegation, and the legal advice was that if they named him or even printed the address of his church, they were risking contempt. When the bishop threw out the complaint and formally exonerated Ampersand, they used that, though.’

‘How long was it between all this happening and the murder?’ I asked.

‘About three years . . . four and a half since the initial complaint. The girl, Briony, she was nineteen by that time.’

‘What can you remember of Alf’s investigation?’

‘Quite a lot. I’d risen in rank, and was an assistant chief when the murder happened. Sir George wanted to keep his hands clean, as he always did, so he told Alf to report progress to me. I protested about that, I said it was borderline improper, but Hume just waved me away and told me to get on with it.’

I was puzzled by that last remark, and quizzed him. ‘Why was it improper, Jimmy? CID always report to the command corridor at some level.’

The look he gave me said a lot, but most of it was that he had let something slip, something he hadn’t meant to. ‘Alf Stein and I were brothers-in-law, Bob,’ he said quietly, as if that would lessen the impact of his words. ‘He was married to my older sister Peggy; she died of breast cancer in her early forties. You weren’t aware of that?’ he added, almost as an afterthought.

‘It’s the first I’ve heard of it,’ I told him truthfully.

He showed me a small smile. ‘Then you’re not infallible.’

‘Alf never mentioned it either,’ I retorted. ‘Never once in all the time I worked for him. As for you and me, while he was around our paths never really crossed, and when they did, I was hardly going to quiz you about your family background.’

‘No, maybe not. We never tried to keep the relationship secret,’ he insisted. ‘But at the same time everybody in the job who needed to know did. They were our senior officers, and they were not the gossipy type. Still, I’m surprised that you never picked up a hint.’

‘You shouldn’t be. I learned early on that if Alf wanted you to know something, he would tell you. His boundaries were set, and they didn’t include talking about his private life. Back then, I was an acolyte; I knew I was his protégé and I was content to sit there and wait for the pearls of wisdom to fall. Occasionally I thought he was less respectful to the chief constable than most, but I put that down to Alf being Alf.’

‘Yes,’ Jimmy agreed. ‘He had a way about him. Now I think about it, I can understand him never mentioning Peggy to you. Her death crushed him. From then on he focused entirely on the job. When. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...