- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

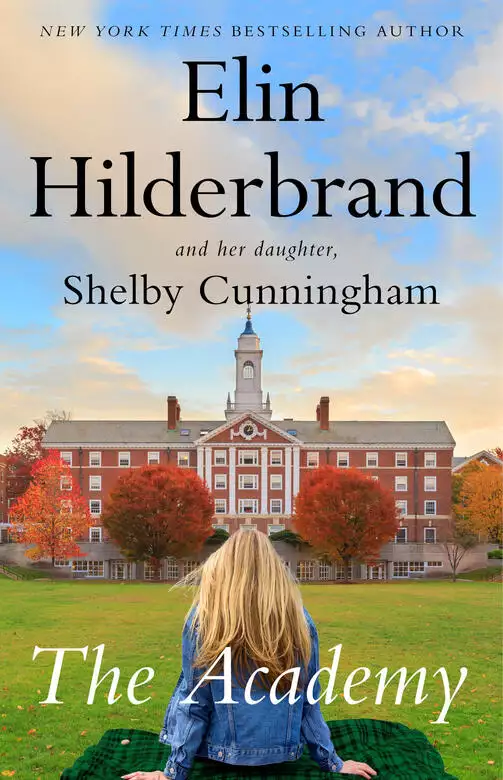

#1 bestselling author Elin Hilderbrand teams up with her daughter, Shelby Cunningham, to deliver a dishy, page-turning novel following an intertwined cast of characters over the course of one drama-filled year at a New England boarding school.

It’s move-in day at Tiffin Academy and amidst the happy chaos of friends reuniting, selfies uploading, and cars unloading, shocking news arrives: America Today just ranked Tiffin the number two boarding school in the country. It’s a seventeen-spot jump – was there a typo? The dorms need to be renovated, their sports teams always come in last place, and let’s just say Tiffin students are known for being more social than academic. On the other hand, the campus is exquisite, class sizes are small, and the dining hall is run by an acclaimed New York chef. And they do have fun—lots of parties and school dances, and a piano man plays in the student lounge every Monday night.

But just as the rarefied air of Tiffin is suffused with self-congratulation, the wheels begin to turn – and then they fall off the bus. One by one, scandalous blind items begin to appear on phones across Tiffin’s campus, thanks to a new app called ZipZap, and nobody is safe. From Davi Banerjee, international influencer and resident queen bee, to Simone Bergeron, the new and surprisingly young history teacher, to Charley Hicks, a transfer student who seems determined not to fit in, to Cordelia Spooner, Admissions Director with a somewhat idiosyncratic methodology – everyone has something to hide.

As if high school wasn’t dramatic enough...As the year unfolds, bonds are forged and broken, secrets are shared and exposed, and the lives of Tiffin’s students and staff are changed forever. The Academy is Elin Hilderbrand’s fresh, buzzy take on boarding school life, and a thrilling new direction from one of America’s most satisfying and popular storytellers.

Release date: September 16, 2025

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Academy

Elin Hilderbrand

Monogrammed duffel bags, mini fridges, field hockey sticks, guitar cases, snowshoes, beanbag chairs, cross-country skis, wireless speakers, makeup mirrors, LED strip lights, extra-long twin sheet sets, skateboards, scooters, a Frank Ocean poster. Audre Robinson—who is in her sixth year as Head of School—helps unload exactly one item from each vehicle. In her first year as Head, she wore a raspberry linen sheath and stacked heels and stood atop the Schoolhouse steps waving to the processional of cars as though she were some kind of royalty. This was how the Heads of School who preceded Audre—all of them white men—comported themselves on Move-In Day. But Audre found it made her feel silly and uncomfortable, not to mention lonely, and so in year two, she donned a pair of mom jeans and a hunter-green Tiffin Thoroughbreds T-shirt (available from the school store for $17.95) and greeted each student and their parent(s) or guardian(s) with a smile, a handshake or (for the returning students she favored) a hug, and the ceremonial unloading assistance.

Audre thinks of each new school year as a blank composition book, a fresh box of sharpened pencils—but this reveals her age. To these kids, it’s… what? An empty Google doc, the cursor blinking at the top of a laptop screen?

Audre is also thinking, Nothing bad has happened… yet. For example, no one has appeared at Audre’s residence between breakfast and Chapel to say that the door to 111 South is jammed and Cinnamon Peters isn’t responding to either knocks or FaceTimes.

She’s always the first one up, Cinnamon’s best friend, Davi Banerjee, said on that fateful day last spring. It was Davi, the queen bee of her class, who was dispatched to the Residence to alert Audre because the head of security, Mr. James, didn’t come on duty until ten. I think something’s wrong.

Something was, in fact, wrong. Hideously, tragically wrong.

Audre shivers despite the heat of the day—early September is still full summer; the temperature is nearing eighty even at this early hour—and she forces a smile for the next car, a Hyundai Sonata with Georgia plates, a rental. Audre sees a woman with a graying ponytail wearing a GO ’BREDS T-shirt in the driver’s seat, and on the passenger side, a boy hunched over his knees. That’s what happens, Audre thinks, when you accordion a six-foot-four frame into a midsize sedan.

It’s Webber “Dub” Austin, the Thoroughbreds’ starting quarterback. He unfolds himself from the car, removes his massive headphones, and rolls his sunglasses up into his bushy hair, which has gotten a few shades lighter over the summer. He has tan lines on his face where his sunglasses rest. What does Dub do for a summer job? Audre wonders. Park ranger? Ranch hand? The hair will be shaved off by tomorrow. In his cowboy accent, Dub says, “Mornin’, Ms. Robinson.”

“Dub,” Audre says, and she rounds the car to give the boy a hug.

By the end of the month, Audre will know every student by name, though she occasionally gets tripped up by all the Madisons and Olivias. She tries not to have favorites—but she feels extra protective of this year’s fifth-form. They’ve been through a lot.

The mother climbs out. The students have a joke where they call one another’s mothers “Karen,” but Dub’s mother is actually named Karen, Karen Austin. She’s the single mom of four boys, of whom Dub is number three; he’s attending on a full scholarship (athletic, though in his case, need-based as well). Dub’s oldest brother played football at Colorado State; the second brother is a wide receiver at CU Boulder. Then there’s Dub. But the real star is apparently the youngest brother, who is starting quarterback as a freshman for their high school back in Durango.

Audre doesn’t usually retain this much information about the students’ families—especially those who never donate—but she has had an earful on the Austin family from Coach Pete Bosworth.

Audre gives Karen a hug as well, and Karen says in her ear, “How’re you doing?”

Audre has anticipated being asked this question several times today, and so she’s formulated an answer that she hopes strikes the right tone. (What is the right tone when a student has died by suicide on your watch, but you have 239 other kids in your care who deserve a top-notch educational experience?)

“We’re all still hurting,” Audre says. “But optimistic about the year ahead.”

Karen releases Audre and says with watering eyes, “Good for you.”

“How’s Dub handling it?” Audre asks in a whisper, though it’s doubtful he’ll hear her. He’s been out of the car for mere seconds and is already being swarmed by Olivia P., Madison R., and Olivia H-T.

Karen stares at the car key she’s gripping in her hand. “You know, he’s my sensitive one.” Then she snaps back into her no-nonsense boy-mom persona and calls out, “Hey, Romeo, help me get this shit out of the car, please.”

Audre opens the Sonata’s back door. Sticking out of a gaping duffel bag is a framed picture of Dub and Cinnamon Peters last Halloween—they went as Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift—with Dub’s hand placed chastely on Cinnamon’s upper back. All the other students considered them #couplegoals. They weren’t gross, they didn’t make out in public, you never heard rumors about them “joining the Harkness Society” (having sex on the Harkness tables) or sneaking down to God’s Basement below the chapel, though they were always together, deep in conversation, laughing. Cinnamon cheered from the sidelines with her face painted green and gold when Dub played football. Dub sat in the front row on the opening night of the high school musical, a bouquet of convenience store roses on his lap. Cinnamon was Sandy in Grease.

At the memorial service in the chapel, Dub called Cinnamon a “friend of his heart.” Not a dry eye, of course.

Audre leaves the duffel bag where it is and grabs a bulk-size box of protein bars from the trunk instead. Her cell phone buzzes in the back pocket of her jeans, but she has to wait for a break between cars before she can check it.

It’s a text from Jesse Eastman, known to all, including Audre’s phone, as “Big East,” the president of Tiffin’s board of directors. Have you seen the rankings yet?

Ugh, Audre thinks.

Before coming to Tiffin, Audre served as Head at an all-girls day school in New Orleans. She didn’t know a national ranking of boarding schools even existed, much less how important the rankings in America Today were to the board, the alumni, and the parents.

When Audre took over as Head of School, Tiffin was a study in mediocrity, the gentleman’s C of boarding schools. Its heyday was long past; the whole place felt like a once-grand hotel desperately in need of a renovation. But alas, there was no money for improvements—they were barely getting by on their operating budget and the teachers hadn’t had a raise in four years. Tiffin’s ranking in America Today (released annually the day after Labor Day) reflected their complacency: They usually appeared somewhere in the lowest tenth of the top fifty—numbers forty-six through forty-nine—and this probably only as a nod to their esteemed past.

But three years ago, Audre—and Cordelia Spooner, head of admissions—met with New York real estate magnate Jesse Eastman about his son, Andrew. Andrew had a “nontraditional” background, which was a euphemism for having been kicked out of two New York City private schools and barely hanging on at a third. Together, Audre and Mrs. Spooner agreed they’d take a chance on admitting Andrew Eastman the following year—and, as tacitly promised, an enormous endowment from Jesse Eastman followed.

They’ve since been able to elevate the entire Tiffin experience—and better rankings in America Today have ensued. Two years ago, they rose to number twenty-four (breaking the top twenty-five was a cause for jubilant celebration), and then last year they appeared at number nineteen (and popped the champagne after breaking the top twenty!).

There are even greater expectations for this year, though Audre tries to keep a clear perspective about the rankings. Nobody knows the algorithm, so what does it really mean? Old Bennington and Northmeadow—both members of the Independent Schools of New England Coalition, to which Tiffin also belongs—have been ranked numbers one and two respectively since Audre has been at Tiffin. Other perennial achievers are the Phillipses (Exeter and Andover) as well as the Saints (Paul, Mark, Andrew).

It’s been rumored that America Today dispatches reporters who pose as prospective parents. They take tours and attend admissions information sessions. They ask current students probing questions. Cordelia Spooner is always on the lookout.

Audre won’t lie: She’s nervous about their ranking this year, especially after what happened in the spring. If Tiffin falls out of the top twenty-five, everyone will blame her and her alone. Just the previous evening, Audre wondered if a dramatic-enough plunge might cause her to lose her job. She shooed the thought away as preposterous, though as a businessman Jesse Eastman is only used to growth, to success. We have to be ranked nineteen or higher, Audre thinks, or there will be hell to pay.

To Big East’s question, Audre replies casually: Not yet. Surely he has an assistant at his zillion-dollar company whose sole duty this morning is to hit refresh on the America Today website. He’ll know before she does.

When Audre takes a sustaining breath, she smells freshly cut grass and the aroma of bacon (both real and vegan) wafting over from the Paddock. Tiffin’s chef is a burly, tattooed gentleman named Harrison “Haz” Flanders, whom Big East hired away from his private club in New York two years earlier. The food in the Paddock—once the subject of a thousand memes—is now so fresh and delicious that nearly the entire Tiffin community has put on the freshman fifteen, Audre included. Chef’s specialties are fried chicken and waffles, homemade focaccia, a new salad bar sourced with heirloom vegetables from a local farm. Haz requested a pizza oven (which Big East promptly donated), and now, every Friday at lunch, Audre can look forward to the “rustica”—bubbling mozzarella and smoky pancetta topped with a handful of lightly dressed arugula. Haz also took the edge off Mondays by instituting Burger Night: charbroiled Angus beef with an array of toppings and sauces, followed by an hour at the new Piano Bar in the Teddy, where Mr. Chuy, the music teacher, takes requests and all the kids sing their preppy little hearts out.

Audre starts to hum “Tiny Dancer” as another car pulls up—a shiny black Escalade with tinted back windows and a uniformed driver.

Here’s Davi.

Davi hops out of the back seat wearing an enormous pair of sunglasses; white low-waisted, flared jeans; and a crocheted, off-the-shoulder crop top. Her bare midriff is a glaring violation of the Tiffin dress code (forbidden: page 8 of The Bridle, Tiffin’s Rules of Conduct), but Audre is too shocked by Davi’s new look to comment about the top (or lack thereof). Davi has cut off most of her shiny dark hair, which used to reach down past her derriere. It’s been replaced by a bob.

She gives Audre a tight hug. “Ms. Robbie,” she murmurs. Davi is the only student in six years brave enough to give Audre a nickname, and Audre has to admit, she’s fond of it. “Thank god I’m back.”

This, Audre thinks, is why she loves her job.

Davi Banerjee, whose parents started the fashion label OOO (Out of Office), is an international influencer. She has 1.3 million devoted Instagram and TikTok followers from twenty-seven countries, and she has more than thirty corporate sponsors. She lives in London with her parents, though Audre has seen, from checking Davi’s social media accounts, that she spent most of her summer at her family home in Tuscany, followed by a quick trip to Ibiza with her glamorous European friends.

Audre likes to believe that Davi is universally loved at Tiffin, though the more accurate term might be “revered.” Davi rules the social landscape mostly benevolently, though Audre is aware that the other girls spend a lot of precious energy currying favor with her; there’s fierce competition to be included in her inner circle. The one person who was exempt from all this was Cinnamon Peters, Davi’s best friend since day one at Tiffin.

In the aftermath of Cinnamon’s death, Davi organized a candlelight vigil, directed donations to a reliable mental health organization, and then went dark on social media. There were times in the days following Cinnamon’s death when Audre thought the school might have fallen apart were it not for Davi.

“Welcome back,” Audre says. “You’ll need to change your top before All-School Meeting.”

“Yes, I know, I know,” Davi says. Her English accent always makes Audre think of chintz and clotted cream. “I promised I’d post myself wearing it… This is the style Akoia Swim named for me.” Davi holds her phone up over her head, wraps an arm around Audre’s shoulders, and snaps a photo of the two of them with the mullioned windows of Classic South behind them.

Will 1.3 million people now see Audre in her mom jeans? No, she thinks. She isn’t cool enough for Davi’s Instagram, and for this she’s grateful.

“Has the new girl arrived yet?” Davi asks.

There are a number of “new” girls this year—thirty third-formers (freshmen), seven fourth-formers (sophomores)—but they’re not who Davi is asking about. Davi is asking about the only new student entering as a fifth-former (junior): Charlotte Hicks from Towson, Maryland, the girl who will be living in 111 South, formerly Cinnamon Peters’s room.

“Not yet,” Audre says. She heads to the back of the Escalade, where Davi’s driver is unloading plastic bins, labeled by designer. Audre reaches for the Hatch alarm clock, new in its box. She feels maternal about Davi. The poor girl flew from London by herself and will be moved into 103 South by a complete stranger. As far as Audre knows, there’s only one other student arriving without a parent.

But Audre needn’t worry about Davi. Within seconds, she’s surrounded by her squad, all of them exclaiming about her hair, her top. You look so cute! Phones are brandished, selfies snapped.

This is as good a time as any, Audre thinks, to step away.

Growing up in New Orleans, Audre had heard of “intuitive” women who were rumored to practice voodoo and have connections to the supernatural. Audre, the daughter of two Tulane professors, viewed this as just another part of New Orleans culture, like jazz and jambalaya. However, Audre herself experiences a fingernails-down-the-proverbial-chalkboard chill from time to time. This “Feeling” has turned out to be prescient: It’s a warning that a threat to Audre’s peace of mind is imminent.

She has the Feeling now. It could be due to the impending news of the rankings, but on a hunch Audre decides to check the Back Lot.

The Back Lot is where the staff parks, where deliveries are dropped off—and where Mr. James sneaks slugs from his flask of whiskey in his garage office.

As Audre stands at the top of the stairs that lead down to the lot, she sees a black GMC pickup pulling in. Audre hears strains of “Many Men” by 50 Cent pumping out the window; it’s so loud she feels it in her tooth fillings.

The truck pulls into its usual spot, the music cuts, the driver gets out. He grew a couple inches over the summer, Audre notes, and his dark hair flops over his aviator sunglasses like he’s a character from Top Gun. He’s wearing Oliver Cabell sneakers, athletic shorts, and a vintage baseball jersey. When he spies Audre, he lifts a hand in greeting.

“Welcome back, Andrew,” Audre whispers to herself. She’s the only person at Tiffin who calls him by his given name; everyone else calls him East. Andrew Eastman, son of Jesse Eastman, is the only student who’s allowed a car, the only student who’s allowed to use the service entrance, the only student granted the freedom to do a lot of things. Audre sometimes thinks the question isn’t if East will get kicked out of Tiffin but when—though bringing any kind of disciplinary action against East would be an existential threat to the school. If East goes, the money goes—and the bright, prosperous future of Tiffin goes. For this reason, Audre has turned a blind eye to his vaping (forbidden: page 2 of The Bridle) as well as his barely passing (and by “barely passing,” Audre means failing) grades in English and history.

As Audre waves back, she sends East a silent message: Don’t do anything this year I can’t forgive. Please.

Stationed in front of Classic North is Rhode Rivera, the person Audre hired to replace Doc Bellamy, the fossilized English teacher who rarely gave a grade above B and never smiled (he’d retired in the spring after forty-two years, hallelujah). Audre had desperately wanted to hire a woman, preferably a woman of color, but Rhode interviewed well and said many promising things. He’d been a student at Tiffin himself twenty-some years ago. Doc Bellamy had been his English teacher, “both inspiring… and intimidating.” Indeed, a check of Rhode’s transcripts showed that he’d received one of the rare A’s Bellamy had granted during his tenure. Rhode went on to college at Wesleyan and pursued an MFA at the University of Michigan. He’d also published two novels. (Audre hadn’t heard of them but had looked up reviews of both books: not bad.)

What had sealed the deal for Rhode’s hiring was his plan to overhaul the English curriculum. He would revamp the reading list, making sure it was current and inclusive.

Before being hired, Rhode had been living in Astoria, working as an adjunct professor at Queens College. It was an urban life, he said, and he was ready for a change.

He looks chipper in his green polo shirt (school-issued, with a racehorse embroidered on the chest) and khaki shorts. (He’s wearing Skechers and white ankle socks; the kids will be merciless.) Most teachers loathe Move-In Day—they consider it glorified manual labor—so it’s no surprise that the only two faculty members Audre could corral are new: Rhode and one of the history teachers, Simone Bergeron, a recent graduate of McGill in Montreal. Rhode and Simone seem to have developed a rapport. Rhode is regaling Simone with the high jinks of his own boarding school days, something about a ferret one of his floormates in Classic North was keeping in a cage under his desk, very much in violation of school rules (forbidden: page 3 of The Bridle, “pets,” listed just below “firearms”).

“Our prefect noticed the smell,” Rhode says. “But he thought it was Townie’s socks.”

Simone’s laugh is like a bell. She gathers her braids into a bun on top of her head and ties a silk scarf around it in a way that seems very elegant and French. “You had a classmate named Townie?”

“Nickname,” Rhode says. “Because he grew up in Haydensboro, the closest town to campus. His parents owned a bar called the Alibi.”

“Is it still there?” Simone asks. “I was wondering if there were any fun places around.”

“If by ‘fun,’ you mean ‘gritty and depressing,’ then yes,” Rhode says. “I’ll take you there sometime.”

“I’d love that!”

Internally, Audre groans. She encourages camaraderie among the faculty, but she has never had two new single teachers before and would have no idea what to say or do if a… romance were to blossom. Will she have to worry about this? Furthermore, Audre likes to pop into the Alibi herself from time to time. It’s gritty but not necessarily depressing—a string of colored Christmas lights hangs over the bar year-round, and the jukebox features songs ranging from Motown to One Direction. Jefferson the bartender keeps a bottle of Finlandia vodka in the freezer expressly for Audre. One or two icy shots followed by a glass of cheap chardonnay, and Audre can forget all about Tiffin for a while. The last thing she wants to do is bump into a couple of teachers on a field trip.

The chapel bells ring to signal ten o’clock, and Audre’s phone buzzes again. She’s about to check it—it’s Big East, she’s certain—when she sees a car approach. Audre gets the Feeling again. It’s a silver panel van, nothing remarkable about it, and yet somehow Audre knows: This is the girl she’s been waiting for. This is Charley Hicks.

Charley’s admission to Tiffin was… unusual. Her application had arrived on May 23, either tragically late or comically early. A quick check revealed the former: Charlotte Emily Hicks was a sophomore at her public school, applying for admission that very September. Tiffin didn’t generally admit students as fifth-formers, though there were exceptions. Such as when Tiffin had an unexpected opening.

Cinnamon Peters had died eleven days earlier.

“This is uncanny, right?” Cordelia Spooner, head of admissions, had said to Audre in a stage whisper. “It’s almost like”—she cast her eyes up toward the ceiling rosette in Audre’s office—“divine intervention.”

Mmmmmm. Audre had thought this might be stretching things a bit. Was Cordelia intimating that some kind of greater power had sent them Charley Hicks of Towson, Maryland?

“Is she Tiffin caliber?” Audre asked. They certainly weren’t going to admit someone just because they happened to have an opening for a fifth-form girl.

“Top one percent,” Cordelia said. “Otherwise I wouldn’t have brought this to you. Her GPA is above a four point oh, she’s taken only honors classes, her PSAT scores were nearly perfect. Her English teacher wrote a glowing letter saying she had never had a student who loved reading as much as Charley. Always reading, apparently. My only concern is that she might be too… brainy for Tiffin.”

Cordelia was right to be concerned: Very cerebral kids didn’t tend to do well at the school, which was aggressively social. The Head of School before Audre used to brag that they were cultivating Tiffin students to be sought-after guests at cocktail parties, though Audre sometimes worried they were raising the next generation of douchebags. “Any extracurriculars?” Audre had asked.

“Editor of the literary magazine,” Cordelia said.

Tiffin didn’t have a literary magazine; Doc Bellamy had tried to start one many times, but not a single student signed up.

“Sports?”

“No.”

The girl will have to acquaint herself with a field hockey stick, Audre thought. “Anything else of note?”

“The letter from her guidance counselor said she was top of her class, a lock for valedictorian. But he also mentioned her mental toughness. Apparently her father died suddenly last fall—he was an attorney with a big firm in Baltimore—but Charley kept her grades up.”

The father dying probably explained why the application was so late. “Attorney with a big firm” had piqued Audre’s interest. “Is she seeking financial aid?”

“No,” Cordelia said. “Full tuition.”

Tiffin wasn’t need-blind, and so it had been this revelation that tipped the scales in Charley Hicks’s favor. Admitting Charley also prevented 111 South from sitting empty. Audre had feared the other girls would light candles (forbidden: page 11 of The Bridle) at séances where they might try to contact Cinnamon’s spirit.

“Should we offer her the spot?” Cordelia had asked.

“Let’s,” Audre said.

The side of the silver panel van says, HICKS LANDSCAPING & GARDEN SUPPLY—TOWSON, OWINGS MILLS, ELLICOTT CITY. The woman who climbs out of the driver’s side—Charley’s mother, presumably—has a suntan, a dark ponytail, and feet in rubber clogs.

Audre recognizes the expression on the mother’s face; she sees it multiple times every Move-In Day: dread, sadness, fear.

“I’m Audre Robinson, Head of School,” she says. “Welcome to Tiffin Academy.”

“Fran Hicks,” the woman says, shaking Audre’s hand. “For the record, I’m one thousand percent against this.”

Ah, okay, Audre thinks. She can never be sure who in the family is “driving the bus” on the decision to go to boarding school—but Audre much prefers it when it’s student-motivated.

“Charley will receive a blue-chip education,” Audre says. “Better than she would at most universities.” She extends a Vanna White arm to showcase the students around them laughing, chatting, playing cornhole. From an open window in Classic North, strains of Luke Combs’s “Beer Never Broke My Heart” float down. (That would be Dub’s room; no one else listens to country music.) “Besides that, she’s going to have a wonderful time.”

Charley climbs out of the passenger side, and Audre takes stock of her new student. Her first thought is, Have we made a terrible mistake? Charley is tall and lanky with sallow skin. Her light brown hair is in two braids; glasses perch on the end of her nose. She wears a kelly-green Lacoste polo, a khaki skirt in a length Audre can only describe as “awkward,” and a belt embroidered with whales. On her feet are boat shoes; Audre hasn’t seen a pair up close in decades.

It looks like she stepped right out of The Official Preppy Handbook; if it were 1984, she would fit right in. But forty years have passed. Now the girls all wear Reformation, Golden Goose, and—for those who can afford it—Davi’s parents’ label, OOO. Audre wonders if Charley watched some old movies—Love Story, perhaps, or Dead Poets Society—and thought this was what the kids would be wearing?

Oh dear. Mr. Rivera’s Skechers are a minor problem compared to what they have here.

But then Audre chastises herself. The girl is fine, it doesn’t matter what she’s wearing; this school could use someone who doesn’t conform.

Charley steps forward to shake Audre’s hand but doesn’t smile. “Thank you for admitting me, even though my application was so late.” Her eyes flick to her mother. “There were extenuating circumstances.”

Audre’s phone buzzes again. “Let me help you unload,” she says. Fran Hicks slides open the side of the van, releasing the pleasant scent of cedar mulch. There are stacked bags of it, along with peat moss, a gas can, a Weedwacker, and a cast-iron planter that must weigh several hundred pounds.

There’s also a plastic bin filled with plants. Charley reaches for one that looks like a small palm tree.

“Are you bringing that in?” Audre asks.

“Yes,” Charley says. “Plants are allowed, right?”

Audre tries to think. The Bridle specifically says no pets—not even a goldfish in a bowl—but does it mention plants? Audre regards the bin. Are all those plants coming inside?

She recalls a student who once nurtured a succulent garden she’d received as a Christmas gift.

Fran Hicks seems to note the ambivalence on Audre’s face. “They aren’t pot plants,” she says. “I told Charley to leave those at home.”

Audre laughs. The Hickses have a sense of humor, a good sign. “Yes,” she says. “Plants are allowed.”

Behind the ferns, topiary, and a leggy philodendron, Audre spies at least a half-dozen milk crates overflowing with… books.

She blinks. Does she recall a student ever bringing books to school? It’s rather like bringing sand to the beach. Audre lifts a milk crate so that she can peruse the titles: The Plot by Jean Hanff Korelitz, Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder, Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi. All books Audre would read herself if she could find the time.

When Fran Hicks opens the back doors to the van, Audre sees more milk crates. More books! Penguin Classics, Vintage Contemporaries, a tattered copy of the Cheever stories. There’s one crate dedicated to poetry: Edna St. Vincent Millay, Anne Sexton, Nikki Giovanni.

Audre is impressed—and a little intimidated. If old Doc Bellamy knew how to use a cell phone, she might be tempted to text him now at his cabin in the woods, up in Robert Frost country. We have a genuine reader!

Audre leads the way to 111 South. Technically, it’s Simone Bergeron’s job to show new girls to their rooms, but Audre wants to do this herself. She swings the door open. The room is clean, orderly, unremarkable: extra-long twin bed, desk, dresser. However, Audre can’t help seeing it as it was on the morning of May 12: Cinnamon Peters splayed across her bed, her skin gray, her mouth open (though eyes, blessedly, closed). On the floor: her acoustic guitar (flipped upside down), her laptop (closed), an empty sandwich bag that had held a cache of pills, half a glass of water. Cinnamon had left a note on her desk that said simply, I’m sorry, tucked under a vase of wildflowers that Dub Austin had picked for her from the Pasture.

“Here we are!” Audre says brightly. She’s waiting for either Charley or her mother to protest—a girl died in this room!—but they simply set Charley’s plants and books d

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...