- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

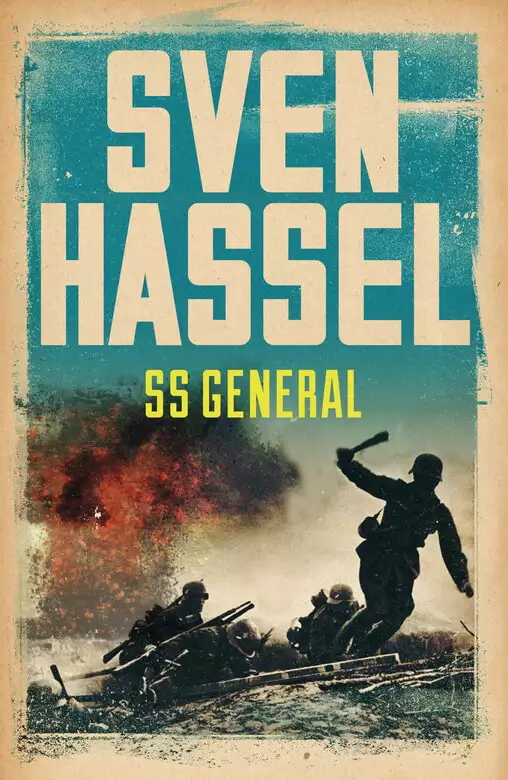

Synopsis

It is freezing 38 degrees. Stalingrad, the winter of 1942-1943. A chilling wind sweeps over the plains, slinging ice crystals into our faces. We are marching past thousands of frozen bodies. The SS-general is marching in front of the convoy, silently and withdrawn. He is angry. We realized that a while back. A fanatic who wishes to die in battle. And the SS-general wants to take as many to die with him as possible. "MOVING STUDY IN THE STALINGRAD CAMPAIGN... POWERFUL, MERCILESS PORTRAYAL OF THE NIGHTMARES OF THE WAR" GLASGOW DAILY RECORD, SKOTLAND

Release date: December 23, 2010

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

SS General

Sven Hassel

Daily Mail, London

10th October 1933

Sunday, 30th June 1934, was one of the hottest days Berlin had ever known, but it has gone down in history as one of the bloodiest. Long before sunrise on that day the city had been surrounded by an unbroken cordon of troops. All roads leading in and out were closed, guarded by the men who served under General Goering and Reichsführer SS Himmler.

At five o’clock on the morning of 30th June, a large black Mercedes, with the inscription ‘SA Brigadenstandarte’ on the windscreen, was stopped on the road between Lübeck and Berlin. Its important occupant, a Brigadier-General, was ordered out at gun-point and thrown into the back of a police wagon. The driver, SA Truppenführer Horst Ackermann, was bluntly advised to move himself, which he did at top speed. He regained Lübeck and made his report to the Head of Police, who at first refused to attach any credence whatsoever to the story. Upon the Truppenführer’s insisting, the man could think of nothing more constructive to do than pick up the telephone and seek help and advice from his old friend the head of the Criminal Police. Both of them had been members of the SA, the old guard of the National Socialist assault troops, but the previous year, along with all the other police officers in the Third Reich, they had been transferred to the SS.

‘So what do you think?’

There was an uneasy silence from the telephone. The Head of Police tried a new tack.

‘Grünert? Are you still there? It’s hardly likely they’d dare lay hands on one of the SA’s best-known officers, is it?’

Another silence.

‘Is it?’ he repeated, nervously.

This time, there was a cynical laugh from the other end of the line.

‘You think not? In that case, I suggest you leave the telephone a moment and take a quick look through the window … You’re behind the times, my friend! I’ve known this was coming for the past few months and more. All the signs were there, for anyone who kept their eyes and ears open … Eicke’s been far too active for far too long, something had to break … Not only that, they cleared the camp at Borgemoor a while ago, and you’re not trying to tell me they’d let a place like that stay empty for very long? Not on your life! It’s been taken over by Eicke’s SS boys and they’re already prepared for full-scale murder down there …’

The Brigadier-General, Paul Hatzke, found himself shut up in a cell at the former cadet-training school of Gross Lichterfeld, now used as a barracks for Adolf Hitler’s personal troops. He sat on a pile of bricks and calmly smoked a cigarette, his legs in their long black cavalry boots stretched out before him, his back against the wall. He was put out at his unceremonious treatment, but he saw no reason to fear for his personal safety. He was, after all, a brigadier-general and commanded fifty thousand troops of the SA. He was also an ex-captain of His Majesty the Emperor’s own personal guards. He was far too big a man for anyone to touch.

Outside the tranquillity of his cell, the world seemed to be in temporary uproar. Men shouted, doors banged, footsteps thudded impatiently along passages and up and down staircases. The SS men who had arrested the Brigadier-General had muttered something about a revolt.

‘Nonsense! No such thing!’ Hatzke had retorted, with angry contempt. ‘Any talk of a revolt and I should most certainly have had word of it. It’s all a ridiculous mistake.’

‘Of course, of course,’ they had murmured, soothingly. ‘That’s all it is … a ridiculous mistake …’

Hatzke tore open his fourth packet of cigarettes and raised his eyes to the small barred window high up in the wall.

A revolt! Arrant nonsense! He smiled to himself. All other considerations apart, the SA didn’t possess sufficient arms to attempt a revolt. On this point at least he was well briefed.

On the other hand, as far as the 1933 revolution was concerned, it was only to be expected that the two million members of the SA should not be altogether satisfied with the treatment they had received. Not one of the pre-revolution promises made to them had been kept; not even the most basic promise to find them work. Some, indeed, had been given positions in the police force, but their ranks were inferior and their wages were lower than the unemployment benefit paid in the times of the Weimar Republic. But while it was certainly true that the men were disgruntled and bitter, from there to an open declaration of war was a gap too great to be bridged. Particularly war against the Führer. If the SA ever were going to rise up, it would sooner be against the Army of the Reich, the number one enemy of the workers.

Hatzke suddenly stubbed out his cigarette and held his head to one side, listening. Was that the sound of gunfire he had just heard? A lorry started up somewhere outside, its engine coughing; a motor-cycle screamed past; a car backfired … Or was it a rifle shot? He could not be sure, but the idea unnerved him. Gunfire in Berlin on this hot summer’s day? It made no sense. Men were going on leave, preparing to meet their girls, lying in the sun …

The palms of Hatzke’s hands grew damp. He clenched his fists. This time there could be no mistake. He could not indefinitely pretend that the sharp crack of rifles was the backfiring of a car. And there it went again … and again … Outside, the lorry was still trying to pull away. It had been joined now by a recalcitrant motor-cycle. The thought crossed Hatzke’s mind that they could have been planted there deliberately, in an attempt to mask the sounds of gunfire … A shudder of anticipation shook his body. What was Himmler’s band of thugs up to this time? You couldn’t shoot men on mere suspicion. Not in Germany. Amongst the savages of South America, perhaps, one expected that sort of brutality. But not even amongst the barbaric Russians – and certainly not in Germany.

Another salvo of shots. Hatzke leaped to his feet, his upper lip awash with perspiration. What the devil was going on out there? They surely weren’t conducting exercises in this weather?

He took an agitated turn about his cell. Could there after all be some truth in this absurd story of an SA uprising? But God in heaven, it was sheer madness!

He tried to arrange his pile of bricks so that he could stand on them and see through the window, but there were not enough for a double row and they collapsed as soon as he put his foot on them.

The firing went on. It was regular and deliberate, meeting with no opposition. It was obvious, now, that this was no exercise. It sounded to Hatzke suspiciously like a firing squad …

He leaned back against the wall, wondering, not for the first time, what evil lay behind the gathering forces of the SS. That sick dwarf, Himmler, for example; vain, irritable and highly dangerous; reputedly a homosexual … Why did the Führer tolerate him? What plans had he made for him? What dark and unsuspected purpose was the man going to serve?

Hatzke turned to face the door as he heard footsteps along the passage. They came to a halt outside his cell. The key turned in the lock. He found himself confronted by an SS Untersturmführer and four soldiers, their steel helmets glinting in the gloom of the passage. They were all members of Eicke’s division, the only division in the SS to wear brown uniforms instead of the familiar black and not to carry the letters ‘SS’ on their collars.

‘About time, too!’ Hatzke faced them, furiously. ‘Someone’s going to be in trouble for this day’s work, and so I tell you! When General Röhm gets to hear about it—’

The Untersturmführer said nothing; merely cut across Hatzke’s words by yanking him out of the cell and pushing him up the passage, flanked on either side by soldiers. He himself strode behind, his spurs clinking and his leather boots creaking. He was a mere boy, scarcely twenty years old. His hair was thick and honey-coloured; his eyes were blue, fringed with long blond lashes. He had the face of an angel, with soft childlike contours and a chin that was baby-smooth. But hatred stared naked from the beautiful blue eyes and the wide mouth was set as hard as granite. They were like that, in the SS: the flower of German youth systematically turned into efficient killing machines.

The great grey buildings of the barracks were washed by brilliant sunshine. Hatzke and his escort marched across the hot paving stones of the courtyard, where not long since children of eight years old had been accustomed to drill. In these same barracks, for years past, children whose destiny was war had been prepared to take their places as uncomplaining cannon fodder in the Army of Imperial Germany. In all the best families of the Reich were to be seen fading sepia photographs of boys of seventeen, dressed up in their heroes’ uniforms and departing in all their false and glittering glory for death in the trenches of First World War France. They died as they had lived, according to the rule book. And who knew but that death might not indeed have been welcome after eight years of training and torture in the courtyards of Gross Lichterfeld?

Hatzke marched on past the stables, now filled not with horses but with weapons. The sound of revving engines was very close. He stopped and turned to his escort.

‘Where are you taking me?’

‘To see SS Standartenführer Eicke.’ The man curled his top lip, derisively. ‘I shouldn’t try anything on, if I were you. It won’t get you anywhere.’

The Brigadier-General grunted and walked on. Time to see about the lack of respect later. For the moment it was sufficient to reflect that for whatever reason they had arrested him, he would at least be guaranteed a fair trial. Men were not shot without a fair trial in Germany. That was what the regulations laid down, and Germany was a country that lived according to the rules. The Führer himself had declared that henceforth there was to be an end to democratic disorder and the start of strict regimentation. Every man should know his rights, and those who attempted to sabotage those rights would pay dearly for it.

They left the stables behind them and went through to a small courtyard, enclosed by high walls. In former days it had been reserved for cadets under arrest. Inside this courtyard were the lorry and the motor-cycle responsible for the distracting noises. The lorry was a large Krupp, a diesel, and the brown-clad SS driver was sitting smoking behind the wheel. He stared without interest as Hatzke and his escort appeared.

In the centre of the courtyard was a group of officers. At the far end was a platoon of twelve men, in two rows of six. The first row were on their knees, their rifles held at the ready; behind them stood the second row, rifles at their sides. Not far off stood a couple more platoons, patiently awaiting their turn in the slaughter. Twenty executions only, and then you were relieved. That was the regulation. Twenty executions … Hatzke tried to turn his eyes away, but the scene held his attention in spite of himself. He had to look back again.

A man in the uniform of the SA was lying face downwards on the damp, red sand. On his shoulder was the gold epaulette of an Obergruppenführer. His body was just sufficiently twisted for Hatzke to glimpse the lapel of his jacket. It was red: the red lapel of a general. Hatzke found himself trembling. He turned his head away and wiped a hand across his brow. It was cold and clammy.

An SS Hauptsturmführer, a sheaf of papers in his hand, walked up to Hatzke. He did not trouble himself with any preliminary courtesies. He merely consulted his papers and barked out the one word:

‘Name?’

‘SA Brigadenführer Paul Egon Hatzke.’

He was ticked off the list. He stood watching as down at the far end of the courtyard two SS men picked up the dead general and slung his body into a cart.

The Hauptsturmführer tucked his papers under his arm.

‘Right. Down to the far end and up against the wall. No shilly-shallying, please, we’ve got a lot to get through.’

Until that moment, Hatzke still had not believed it could be true; and had certainly not believed it could ever happen to him. He turned on the man in sudden, abject terror.

‘I want to see Standartenführer Eicke! I’m not going anywhere until I’ve seen him! If you think—’

He stopped short as he felt the hard butt of a pistol being dug into his kidneys.

‘That’s quite enough of that. I’m not here to talk, I’m here to carry out my orders. Besides, shouting will get you nowhere.’

Hatzke jerked his head round, seeking somewhere – somehow, from someone – a grain of hope or pity. But the faces he saw beneath the steel helmets were merciless in their very indifference. And the wall at the far end of the courtyard was splashed with blood, and the sand was crimson and a thin red stream was gurgling along the gutter and into the drain.

‘I’m warning you,’ said the Hauptsturmführer. ‘I’ve got a schedule to keep to.’

Someone slapped Hatzke hard across the face and tore open half his cheek with the sharp edge of a ring. As he stood there, the blood splashed down on to his collar and his gold epaulettes, and he knew with a clarity that amazed him that this was indeed the end. His own end, and the end of a vision that had dreamed up a socialist state where the word justice should at last have some meaning. Heydrich and Goering had gained the upper hand and Germany was lost.

Very calm, very dignified, Brigadier-General Paul Egon Hatzke walked across the courtyard and took up his position against the blood-splashed wall. With arms crossed and head held high in defiance, he awaited his death.

The firing squad raised their rifles. Hatzke looked across at them with neither fear nor hatred, but a kind of patient resignation. He felt himself to be a martyr in a great cause. As the rifles fired in unison, he shouted out his final words on earth: ‘Long live Germany and Adolf Hitler!’ and crumpled up into the warm, welcoming sand.

The next SA officer was already being brought into the courtyard. The slaughter continued throughout the day and well into the night. Word was sent to Eicke that the men who were dying, the men who had been his former comrades, were one and all expressing a wish to speak with him. He waved his hands impatiently. He was a man with a mission, he had no time to indulge in sentimental farewells.

‘Get rid of them! Just check their names and get it over with! They’re there to be shot, and the quicker the better.’

The furies and follies of that day were not quickly forgotten in Germany. It was those massacres of 30th June which accelerated the rise to power of a trio of men: Himmler, vain as any peacock and hitherto a totally unknown bureaucrat; Heydrich, a disgraced naval officer; and Theodor Eicke, a publican from Alsace.

Fifteen days later, the soldiers who had formed the firing squads, together with all but four officers, were thrown out of the SS – a total of six thousand men. Before the year was out, three thousand five hundred of them had been executed under various trumped-up charges. It was an idea of Eicke’s, a final clean sweep, as it were, and it was loudly applauded by an appreciative Goering. Those who survived were packed off to the waiting camp at Borgemoor, where for the most part they were simply left to rot. According to Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda, they had met their death while quelling the SA revolt, and Rudolph Hess even went so far as to hold them up before the public as brave men and martyrs.

The Führer, of course, had known all along of the plans for the massacre. He had taken care to remove himself to more pleasant surroundings on that hot summer’s day, and even as the murders were being carried out, Adolf Hitler was enjoying himself as a guest at a wedding party at Gauleiter Terboven’s house in Essen …

Somewhere on the road before us lay Stalingrad, and we stopped the tank and stepped out into the open air to have a look. We recognised the town in the distance, by the thick clouds of smoke that still hung overhead, the thin wisps that still curled upwards into the mists. It was said that Stalingrad had been burning since August, since the dropping of the first German bombs.

There was not much joy in looking ahead: there was nothing lying in wait for us there but death and destruction. There was no joy at all in looking back: what had passed was a nightmare best forgotten. So we stared down instead towards the far-off river, the silver ribbon of the Volga, where the dancing rays of the autumn sun made shining rings on the water. And for a short while we were almost hypnotised into believing that the present could last for ever, and the past could be wiped out and the future avoided …

But the tank that had borne us through the past was a solid reality at our sides, waiting to carry us on into the inevitable future, and there could be no escape. For four months we had lived in that tank – slept in it and eaten in it, fought our battles in it, both with each other and with the enemy – until we had become as much dependent on it as a tortoise on its shell. The only times we had ever come to a halt were to take on more fuel or more ammunition, and even then the supplies had been brought to the doorstep while we sat and waited in our steel burrow. Small wonder we had long ago begun to hate each other more than we hated the Russians! Within the four walls of the tank there were perpetual warring factions, feuds and blood-baths and petty squabbles which ended in a man half dead or at the least disfigured for life. The latest victim was Heide. He and Tiny had come to blows over a missing hunk of stale black bread, and when the rest of us had lost patience with two bodies crashing into us and kicking us and raining stray blows upon our heads, we intervened in the matter ourselves and passed judgement against Heide, with the result that he was condemned to travel the next hundred kilometres lashed to the outside of the rear door. It was not until he dropped unconscious, saturated in carbon dioxide, that we remembered his presence and hauled him back to safety.

All day long the tank rumbled on towards the Volga. Shortly after sunset we made out the shape of another tank, stationary at the edge of a wood. A man was sitting on the turret, calmly smoking a cigarette and contemplating the smoke as it rose into the dusk. Both he and the tank seemed marvellously at peace with the world.

‘Must have caught up with the rest of the Company at long last,’ said Barcelona.

‘Thank God for that.’ The Old Man shook his head, wonderingly. ‘I’d begun to wonder where the bastards had got to. These Russian maps are bloody well impossible, they all seem to be at least a hundred years out of date.’

We moved slowly up to the edge of the wood and Porta pulled to a halt a few metres from the other tank. Joyfully we pushed open the observation slits and allowed the fresh night air to penetrate the sweaty hell of our prison. The Old Man hoisted himself out into the open and called across to the unsuspecting smoker.

‘Hi, there! I thought we’d never make it, we’ve been looking for you all over the place. What the hell have you been up to?’

He was about to jump down to the ground when the other man tossed away his cigarette, made a dive for the hatch and disappeared inside the tank like a fox going to ground.

‘It’s the Russians!’ yelled the Old Man.

As he fell back amongst us, we prepared for combat. We were lucky: the enemy, lulled no doubt by the calm of their surroundings, must have taken the opportunity for a nap. Even before they had managed to swing their cannon round to face us we had sent an S grenade, super-explosive, straight into their turret. At that range, we could hardly miss. The tank was transformed instantly into an active volcano, throwing up great chunks of mutilated men and machinery and belching black smoke and yellow flames into the dusky sky.

Carefully now, with observation slits closed and ears and eyes on the alert, we nosed our way forward in a wide detour.

‘Enemy tanks ahead!’

Porta pulled to a halt once again. Several metres ahead, tucked away at the side of the road, were nine T34s. They looked peaceful enough, expecting no trouble, but their guns were all turned in our direction. The Old Man hesitated. The Russians had obviously not spotted us yet, but they were almost certain to do so if we turned about and retraced our path.

‘OK.’ The Old Man nodded at Porta. ‘Start her up again, full steam ahead. We’ll just have to try and bluff our way through.’

He opened the hatch and peered out. In the gloom of the approaching night his helmet looked not unlike its Russian counterpart. He was gambling on the chance that the enemy were not expecting any German tanks to be in the vicinity.

As we moved forward, it occured to me that none but a complete cretin could fail to notice the difference between the sound of our engine and that of a T34, but possibly the Russian crews were tone-deaf. At all events, they made no hostile gestures, merely waving at us and giving us the thumbs-up as we passed. The Old Man responded graciously, while we sat and sweated inside.

An hour later and we appeared to be approaching civilisation. Isolated houses, and then little knots of them, and finally long straggling rows, and we knew we were coming to a town. We drove past a station, where a goods train stood roaring and puffing. We drove through to the town centre. The place was crawling with enemy tanks and soldiers, but in the darkness and the general confusion we passed unnoticed. As we slowly emerged on the far side a policeman waved us down and yelled at us to give way to an armoured car containing some general in a hurry. We obediently fell back and allowed him to pass.

Not far out of town we found ourselves tagging on to the end of a column of Russian tanks. Under their protection we moved past a battery of anti-tank guns and parted company, quite reluctantly on our part, when we came to a crossroads, the Russians going straight on while we turned off for Stalingrad.

The roads were full of traffic. We had not gone far before we had once again to run the gauntlet, passing along the length of a column of stationary T34s. They let us go by without comment, and we guessed that their crews were snatching what sleep they could before being pushed once more into battle.

After the tanks, an infantry battalion, footslogging it along the road. They resentfully parted to make way for us, but our passage was punctuated by oaths of such vehemence and vulgarity that they might almost have known us for the enemy we were.

Another detour, to avoid taking the road through a forest, and we were at last on the way back to our own lines.

Three days later, the Company had reached the banks of the Volga, twenty-five miles north of Stalingrad, and there was an uncontrolled scramble down the slopes to fill our water-cans. It seemed that everybody wanted to claim the privilege of being the first man to taste the Volga.

It was, at this point, about fifteen miles across from bank to bank. The scene looked peaceful and pleasant enough, with a small tug-boat pulling a string of barges behind it and not a tank or a soldier in sight, apart from ourselves. Suddenly, as we splashed about on the bank, a battery of 75s went into action. Great spouts of water rose into the air and the unfortunate tug began a frenzied zigzag in an effort to avoid the worst of the onslaught. She might as well have saved her energy, she stood no chance whatsoever. Shells fell fore and aft, to right and to left of her, and finally, and inevitably, one landed amidships and the little tug snapped in two like a matchstick. The barges floated erratically onwards, a flock of silly sheep without their leader, and the 75s picked them off at will. Ten minutes later and the river was peaceful once again. Had it not been for the wreckage still floating on the surface, the little tug and her charges might never have existed.

Stalingrad was still burning. From where we were, the pungent odour of roasting flesh and cinders, of brick dust and ash, was carried to our nostrils and made us retch. It was a smell that clung to our hair, to our clothes, to our very skin, and it was to be with us for months afterwards.

We had seen many cities burn, but never a city that burned like that one. The sight and the smell of Stalingrad, voraciously devouring itself as it roared headlong towards its own death, was something that etched itself deep into our memories, and none who experienced it could ever forget.

The Company dug itself in opposite the hills of Mamajev, where an entire Russian staff was entrenched in a network of old grottos. During the night our heavy mortars bombarded the face of these hills, keeping up a constant barrage, hour after hour. Whenever they fired short, the blast of their high-explosive grenades almost tore us bodily from the trenches. Tanks went into action, but without any success. The bombardment renewed its fury and the 14th Panzer Divison was finally sent in and managed to push ahead through the grottos and sweep them clean with flame-throwers, assisted by small-arms fire. No prisoners were taken. Any men captured were killed outright. Any who attempted to surrender were slaughtered before they had time to speak. It was the sort of bloodbath the SS might have enjoyed, but for most of us it was a sickening and degrading exercise in murder, forced upon us by one of those uncompromising orders from the top, which made wild beasts out of human beings and merely incited the Russians to return outrage for outrage and swear to fight until death rather than give in.

Summer had given way to autumn, and autumn was now giving way to winter. Slowly, at first, so that we scarcely noticed the creeping cold and only complained bitterly of the incessant rain which fell in torrents from the grey skies and turned the ground into one vast, squelching bog that sucked at our boots as we marched through it. It rained for three weeks without stopping. Men and uniforms began to acquire a greenish tinge. We smelt of mould, and clumps of furry white mildew sprang up overnight. We were given a special powder, which we ritually sprinkled over ourselves and our equipment, but it had no noticeable effect.

After the rain came the cold, and the first of the nightly frosts. We were still forbidden to wear greatcoats, but in any case hardly anyone had a greatcoat left to wear. They had either been lost during the course of a battle or deliberately discarded back in the summer, when we had been fighting on the steppes in temperatures of 100°+ in the shade. Deliveries of winter uniforms were promised regularly from day to day, but they never came. Instead, they sent us some more troops, lorry loads of reservists older than God and probably unfit even to run for a bus, or raw recruits with beardless faces and innocently shining eyes. They came to us to fight in the hell of Stalingrad, fresh from their training colleges and barracks. They had no idea of what war was about, but they had been pumped full of propaganda and a determination to die for a useless cause. They flung themselves straight away into the fighting, into the gaping mouths of the Russian guns. There was nothing to be done in the face of such ignorant heroics. Their misplaced zeal took us all unawares and we could only stand back and listen to them die, as they lay limbless and moaning on the ground or hung screaming in the barbed wire and were used for enemy target practice.

That first mad suicidal gesture was enough to knock all the spirit from the few who survived. Propaganda was thrown back where it belonged, on the rubbish dump, and reality took over. They walked about with glazed eyes and defensively hunched shoulders, treating the enemy with the respect they deserved and placing the value of their own lives far higher than any spectacular death for Adolf Hitler and the Fatherland. Nevertheless, they made no complaints, these babes in arms and old men who had been forced to volunteer for active service. They were still Germans, and Germans were too proud to whine. They suffered the discomforts of the battle in silence, and they went on dying in vast numbers.

We had been promised one day of leave for every twenty recruits we managed to salvage from the field of slaughter, but it was a dangerous game and for the most part we resisted the temptation. More men were lost as they squelched through the mud in search of survivors, slipping on pieces of raw human flesh and tripping over mildewed bodies, than were ever recovered. The Russians were on the look-out for such rescue attempts and they had an unnerving tendency to release a barrage of fire at the least sound. Seven of our own men were lost in that way, and from that moment on we turned our backs on the lure of extra leave and let others chase after the mirage if they would.

The net slowly tightened round Stalingrad, where three Russian armies were said to be trapped. ‘The greatest victory of all time!’ screamed the propaganda machine, but we no longer cared for victory. All we wanted was to save our own skins and see out the end of the war. Only Heide showed any signs of enthusiasm.

‘You just wait!’ he told us, with a fanatical excitement that left us totally unmoved. ‘After Stalingrad – Moscow! We’ll be there, you see if w

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...