- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

It feels as if the entire area is blown up. A long rumbling explosion shakes the German position. Then an infernal scream sounds. Through flashes of fire, they see Tiny's huge silhouette with the light grey bowler on his head. He is standing by the end of the enemy trench with his machine gun resting on his hip. The tracer streak projectiles shoot out of the muzzle. Bewildered shapes flee in panic. - What a bunch of devils, the Russian lieutenant exclaims in admiration.

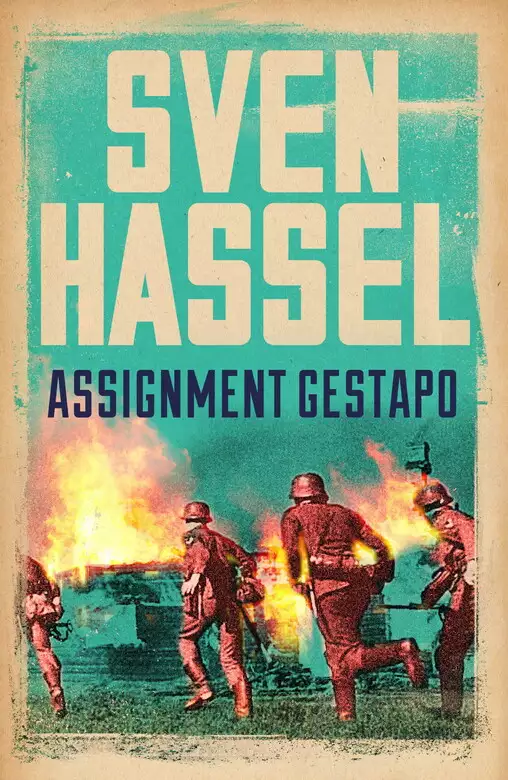

"A BRILLIANT SVEN HAZEL, MAYBE THE BEST. AN INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS NON THE LESS" L'ECHO DE LA VENTE, FRANCE

Sven Hassel was sent to a penal battalion as a private in the German forces. Intensely and with brutal realism, he portrays the cruelty of the war, the Nazi crimes and the crude and cynical humor of the soldiers. With more than 50 million sold copies, this is one of the world's best selling war novels.

Release date: July 22, 2010

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Assignment Gestapo

Sven Hassel

We watched them come with jaded eyes. No comments had been passed, and none was necessary: the approaching troops spoke for themselves. It was obvious to us that we could have nothing in common. We were soldiers, while they were only dilettantes. It showed in the careful way they carried their equipment; it showed in their stiff and shining boots. So beautifully polished and so utterly useless! No one could march very far in boots of such uncompromising newness. They had yet to be rubbed with their baptismal urine, which was the best treatment we knew for softening up and at the same time preserving the leather. Take Porta’s boots, for an ideal example of a soldier’s footwear: so supple that you could see every movement of his toes inside them. And if they gave off an almost overpowering stench of urine, that seemed a small price to pay for comfort.

‘You stink like a thousand pisshouses!’ Porta was once told, rather sharply, during the course of a parade.

That was our Colonel, sometimes irreverently known as Wall Eye, on account of the black patch he wore over one empty socket. It seemed to me significant that in spite of his testy observation on the subject of urine, he never put a stop to our habit of pissing on our boots. He’d been in the Army long enough to know that it’s the feet that make the soldier. You got bad feet and you’re worse than useless.

Tiny, still watching the arrival of the reserve force, suddenly nudged the Legionnaire in the ribs.

‘Where.d’you reckon they dug that lot up from? Jesus Christ, it’s enough to make a cat laugh! The Ruskies’ll mop them up before they’ve even found out what they’re supposed to be doing here . . .’ He nodded importantly at the Legionnaire. ‘If it weren’t for people like you and me, mate, we’d have lost this perishing war years ago.’

The Old Man laughed. He was trying to shelter from the pouring rain beneath a rather pathetic bush.

‘High time they gave you the Knight’s Cross . . . a hero like you!’

Tiny turned and spat.

‘Knight’s Cross! You know where they can stick that, don’t you? Right up their bleeding arses . . . I wouldn’t give you tuppence for it!’

There were sounds of cries and curses from the officers at the front of the approaching column. One of the privates, a little frail creature who looked older than God, had lost his tin helmet. It had rolled to the side of the road with a noise like a hundred tin cans collapsing, and the old chap had instinctively scrambled off the truck and gone toddling after it.

‘Get back into line!’ roared an Oberfeldwebel, outraged. ‘What the bleeding hell do you think you’re bleeding playing at?’

The old boy hesitated, looking from his precious helmet to the apoplectic Oberfeldwebel. He scuttled back into the ranks and marched on, and the Oberfeldwebel nodded grimly and remained where he was, blowing his whistle and every so often shouting his lungs out, intent on hustling these raw amateurs on their way to certain death.

As I watched the column advancing, I could see that the little old man was already near to breaking point; both physically and mentally, I guessed. The loss of his tin helmet had probably been the final straw.

Lt. Ohlsen, our Company Commander, was standing to one side chatting to his counterpart, the lieutenant who had led the reserve troops up here. Neither of them had noticed the incident, neither of them had noticed that one of their men was on the point of cracking. And even if they did, what could they do about it? At this stage of the war, it was a commonplace occurrence.

The old chap suddenly fell to his knees, began crawling down the hill on all fours. His fellow soldiers looked at him nervously. The Oberfeldwebel came running up, bellowing.

‘Stand up, that man there! What do you think this is, a bleeding tea party?’

But the old man never moved. Just lay on the ground, sobbing fit to break your heart. He wouldn’t have moved if he’d been threatened with a court martial; he couldn’t have. He didn’t have the strength left, and he didn’t have the will any more, either. The Oberfeldwebel walked up to him, stood over him chewing at his lower lip.

‘All right . . . all right, if that’s the way you want to play it, I’ll go along with you . . . You’ve got to learn a thing or two, I can see that . . . You think you’re exhausted, eh? Well, just you wait till you’ve got a load of screaming Ruskies coming at you, you’ll move fast enough!’ He suddenly stepped back and rapped out an order. ‘Pick up that spade and get digging! At the double, if you don’t want to get mown down!’

Obediently, the little old chap groped for his spade, which had fallen from his pack. He began trying to dig. It was comical and pathetic. The rate he was going, it would take him the next thousand years to dig a hole for himself. According to regulations, it should take a man no more than 11½ minutes from the time he got the spade in his hand. And God help anyone who took a second longer! Of course, when you’d been in the front line as long as we had you learnt to do it in even less time – you had to, if you wanted to survive. And we’d had enough practice to put us in the champions’ class. The holes we’d dug stretched in a practically unbroken line from the Spanish frontier to the summit of Elbroux in the Caucasus. And we’d dug them in every conceivable sort of terrain. Sand, snow, clay, mud, ice – you name it, we’d dug holes in it. Tiny was particularly gifted in that direction. He could provide himself with a dug-out in 6 minutes 15 seconds flat, and he boasted that he could do it even quicker if he really put himself out. He probably could have, only he was never put to the test because no one ever set up a new record for him to aim at.

The Oberfeldwebel stretched out a foot and pushed at his victim.

‘Come on, grandfather, you’re not building sandcastles! At this rate we’ll all be dead and buried before you’ve even scraped away the first layer!’

Grandfather suddenly expired. Just lay down and died, just like that, without even asking permission. The Oberfeldwebel seemed genuinely astonished. It was a good few seconds before he turned round and bellowed to the two nearest men to come and pick up the body.

‘Call themselves bloody soldiers,’ he muttered. ‘God help Germany if this is what’s being used to protect her . . . but just you wait, you innocent load of bastards! I’ll get you licked into shape before you’re very much older!’

Oberfeldwebel Huhn, the terror of Bielefeldt, rubbed his hands together in anticipation. There weren’t many men he couldn’t lick into shape, once he’d set his mind to it.

And perhaps, after all, his treatment of the old man had had its effect: certainly none of the others dared to collapse.

‘What a callous bastard,’ said Porta, carelessly; and he stuffed his mouth with a mutton sausage rifled from a dead Russian artilleryman.

We were all eating mutton sausages. They were stale and salty and hard as stone, yet they tasted pretty good for all that. I looked at my half-eaten sausage, and I remembered the occasion when we had acquired them: only five days ago, and it seemed five months.

It was on our way back through a vast tract of thickly wooded land that we had stumbled upon the Russian field battery. As usual, it was the Legionnaire who had first spotted them. We attacked with more speed and stealth than even Fenimore Cooper’s Indian braves, cutting them down silently with our kandras.1 By the time we’d finished it looked as if a heavy shell had exploded in their midst. We had come upon them quite out of the blue. They had been lying in a clearing, sleeping, sunbathing, relaxing, totally unprepared for any sort of attack. Their chief had been drawn out of his hut by the sounds of the struggle. We heard him calling out to a lieutenant, his second-in-command, just before he appeared.

‘Drunken bloody swine! They’ve been at the vodka again!’

Those were his last words. As he appeared at the entrance of the hut, his head was severed from his shoulders by one well-aimed blow, and two spouts of hot blood burst from his body like geysers. The lieutenant, who was behind him, didn’t stop to inquire what was going on. He turned and plunged into the undergrowth, but Heide was on him almost immediately with his kandra. The lieutenant fell like a stone.

We were horrible to look upon by the time the massacre was over. And the scene of the carnage was like some nightmare from a butcher’s shop. Several of us vomited as we surveyed it. The spilt blood and the trailing intestines smelt disgusting, and there were thick black knots of flies already settled on every juicy morsel. I don’t think any of us really liked the kandra, it was too primitive, too messy – but, on the other hand, it was an excellent weapon in certain circumstances. The Legionnaire and Barcelona had taught us how to use it.

We sat down on the ammunition boxes and the shells, with our backs to the corpses. We were not so squeamish that we denied ourselves the pleasure of eating Russian sausages and drinking Russian vodka. Only Hugo Stege seemed to have no appetite. We all used to make fun of Stege on account of he’d had a good education and was reputed to be brainy. Something of an intellectual. And also because no one had ever heard him swear. That in itself seemed to us totally abnormal, but even more incredible behaviour came to light when Tiny discovered that Stege always, and assiduously, washed his hands before eating!

The Old Man regarded the store of sausages and the crate of vodka.

‘Might as well take them with us,’ he decided. ‘Those poor devils won’t be needing them any more.’

They had an easier death than many,’ remarked the Legion-naire. They never really knew a thing about it.’ He ran a finger down the razor-sharp edges of his kandra. ‘Nothing brings death as quickly as one of these.’

‘I find them disgusting,’ said Stege, and vomited for about the third time.

‘Look, they asked for it,’ argued Porta, fiercely. ‘Lazing about with their thumbs up their bums and their brains in neutral . . . there is a war on, you know! It could just as easy be us lying down there with our heads hacked off.’

‘That doesn’t make it any better,’ muttered Stege.

‘So.what are we supposed to do about it?’ Porta turned on him, furious. ‘You think I enjoy ripping people’s guts out? You think I like this sort of life? Did anyone ever bother to ask you, when they dragged you into the flaming Army – they ever bother to ask you if you wanted to go round killing people?’

Stege shook his head, wearily.

‘Spare us your home spun philosophies,’ he begged.

‘Why?’ said the Legionnaire, rolling his cigarette from one side of his mouth to the other. ‘It may be simple, but it’s none the less true . . . we’re here to kill, whether we like it or not. It’s the job we’ve been given and it’s the job we’re expected to do.’

‘Besides,’ added Porta, beating wildly at a cloud of flies that was trying to get up his nose, ‘I don’t remember you being particularly backward when it came to clobbering people . . . and what about when you took the thing in the first place?’ He jerked a thumb at Stege’s kandra. ‘What about when you nicked it off that dead Rusky? What was the point of taking it if you didn’t intend to use it? You didn’t want it for cleaning your nails, did you? You took it in case you needed it to stick in somebody, just like the rest of us.’

At this point, the Old Man dragged himself to his feet and jerked his head impatiently.

‘Come on. Time we were moving.’

Unwilling and protesting, we nevertheless picked ourselves up and formed a column, single file, behind the Old Man. We moved off through the trees, to be joined shortly afterwards by Tiny and Porta, who, following their usual practice, had stayed behind to do a bit of looting. From the state of their faces, there seemed to have been some disagreement between them, and it looked as if Porta had been the victor: he was proudly displaying two gold teeth, while Tiny had only one.

As always, the Old Man raved at them without it having the least effect.

‘One of these days I’m going to shoot the pair of you. It makes me sick! Yanking the teeth out of the mouths of dead men!’

‘Don’t see why, if they’re already dead,’ retorted Porta, in cocky tones. ‘You wouldn’t leave a gold ring to rot, would you? Or set fire to a bank note? So what’s the difference between them and teeth?’

The Old Man continued silently to simmer. He knew, as well as the rest of us, that in every company you always had your actual ‘dentists’, who went round the corpses with a pair of pincers. There was little, if anything, that could be done about it.

And now, five days later, we were sitting beneath the fruit trees, watching the reserves come up and stuffing ourselves with mutton sausages. The rain was slashing down, and we pulled our waterproofs higher over our shoulders. These waterproofs served a variety of purposes, being used, according as circumstances demanded, as capes, tents, camouflage, bedding, hammocks, shrouds, or simple sacks for carrying equipment. A waterproof was the first item to be handed to us when we went to collect our kit, and it was the one we valued above all others.

Porta screwed his head round and squinted up into the wet sky.

‘Bloody awful rain,’ he muttered. ‘Sodding awful mountains . . . worst bleeding sort of country you can get . . .’ He screwed his head back again and glanced at his neighbour. ‘Remember France?’ he said, longingly. ‘Jesus, that was something! Just sitting on your arse in the sun, drinking wine till the cows came home . . . that was something, eh? That was quite something!’

Heide was still staring moodily down at the approaching column of men. He pointed with his mutton sausage towards Huhn, who had tortured the little old fellow with the tin helmet.

‘Going to have trouble with that one,’ he said, sagely. ‘Feel it in my bones.’

‘No bastard gives us any trouble and gets away with it!’ declared Tiny. He glared in the direction of Heide’s pointing finger. ‘Let him just try and he’ll get what’s coming to him . . . One thing I am good at, that’s exterminating rats like him.’

‘That’s all any of us are likely to be good at, by the time the war comes to an end,’ said Stege, bitterly. ‘Killing people . . . that’s all it’s taught us.’

‘At least it’s something useful,’ jeered Tiny. ‘Even in peace-time, I reckon, there’s always a need for professional killers . . . ain’t that so?’

He jabbed at the Legionnaire for confirmation. The Legionnaire solemnly nodded. Stege merely turned away in disgust.

The lieutenant who had brought up the reserve troops now began to assemble them in ranks preparatory to his own departure. He had delivered them as ordered and was now suddenly anxious to be gone, prompted perhaps by some instinct warning him that it would not be wise to hang about too long. The area was not a healthy one.

With the men ranged before him, he delivered his parting speech. They heard him out with an air of total indifference.

‘Well, men, you’re at the Front now, and pretty soon you’ll be called upon to fight against the enemies of the Reich. Remember that this is your chance to win back your good names, to become honourable citizens of the Fatherland and earn the right to live amongst us once again as free men. If you acquit yourselves well, all marks against you will be expunged from the records. It’s entirely up to you.’ He scraped his throat selfconsciously and fixed a stern eye upon them. ‘Comrades, the Führer is a great man!’

There was total and uncompromising silence following this observation. And then Porta’s evil laugh rang out, and I’m pretty sure I caught the muttered comment, ‘Balls!’ In all the circumstances, it seemed a likely enough sort of comment. The lieutenant swung round and let his glance range over us. The blood poured up his neck and into his cheeks. He stiffened, and his hand went automatically to his holster. He turned back to his own band of villains.

‘Let there be no doubt in your minds! All your actions will be noted and recorded!’ He paused, significantly, to let this sink in. ‘Do not disappoint the Führer! It is up to you to take this opportunity of making amends for the crimes you have committed against Adolf Hitler and against the Reich.’ He breathed deeply and glanced once more towards the twelve of us, sheltering beneath the apple trees. He met the defiant stares of Tiny and Porta, the one looking a complete half wit, the other with a face as low and cunning as that of a fox. He blenched slightly, but nevertheless pressed on. ‘You will find yourselves fighting side by side with some of the bravest and best of Germany’s sons . . . and woe betide any one of you who shows himself a coward!’

His voice went droning on. The Old Man nodded, appreciatively.

‘I like that,’ he said. ‘The bravest and best of Germany’s sons . . . Tiny and Porta! That’s a laugh!’

Tiny sat up indignantly.

‘What’s so funny about it? I’m certainly the bravest and best of my mother’s sons—’

‘God help us!’ said Heide, shuddering. ‘I presume she hasn’t got any others?’

‘She did have,’ said Tiny.

‘What’s happened to ’em then?’ Porta looked at him challengingly. ‘They get killed or something?’

‘I’ll tell you. The first one, bleeding idiot that he was, went off voluntarily to the Gestapo – voluntarily, I ask you! Bloody fool . . . Stadthausbrücke, number eight,’ recited Tiny, as if it were engraved for ever on his memory. ‘They wanted him for questioning about something or other – I forget what exactly. Something to do with painting slogans on a wall. He was a great lad for painting slogans on walls . . . Anyway, he went off one fine day and wasn’t never seen again . . . And as for the next one – as for Gert—’ He shook his head, contemptuously. ‘You know what he went and done?’

We all wonderingly assured him that we didn’t. Tiny made a gesture of disgust.

‘Only went and volunteered for the bleeding Navy, didn’t he? Ended up in a U-boat, didn’t he?’

‘What happened to him?’I asked.

Tiny spat. Heroes were evidently not in his line.

‘Went down with the bleeding boat, beginning of ‘40 . . . We had a post-card from Admiral Doenitz about it. Lovely, it was. It said, Der Führer dankt Ihnen.2 ‘And it had a lovely black border and all.’ He suddenly gave a short bark of laughter. ‘Bet you can’t guess how that ended up!’

We could, knowing Tiny, but we didn’t want to ruin his story.

‘My old lady used it to wipe her arse on . . . Went to the shit house one day, discovered she didn’t have no bog paper in there, so she calls out to me to bring her some what’s nice and soft. Well, I couldn’t see no newspaper nor nothing, so I grabbed up the Admiral’s post-card and shoved that through the door to her . . . She was calling him all the silly buggers under the sun, afterwards. Scraped her bum to pieces, it did. Hard and rough, she said it was. Hard and bleeding rough . . .’

We roared our appreciation, and Tiny roared louder than any of us.

‘So now you’re the only one left?’ I said, when the laughter had died down.

‘That’s it,’ agreed Tiny, proudly. ‘Eleven down, one to go . . . The Gestapo nabbed some of ’em. Three got drowned at sea. The two youngest kids, they was burnt alive in an RAF raid. Their own stupid fault, mind you. Refused to go into the shelter, didn’t they? Wanted to stay up top and see the bleeding planes go by . . . well, they saw ’em all right!’ He nodded, owlishly. ‘So anyway, there’s only me and the old lady left now. And that’s some doing.’ He looked round at the rest of us, studying each in turn. ‘I bet there ain’t many of us have, sacrificed what we have. Eleven at a blow, and all for Adolf . . .’ He gnawed hungrily at his sausage and took a turn at the vodka bottle. ‘Sod the lot of ’em!’ he decided, defiantly. ‘So long as I get out of it alive, I don’t care no more . . . and something tells me that I’m still going to be here at the end.’

‘That wouldn’t surprise me in the least,’ murmured the Old Man.

The Legionnaire was crouched over a cooking pot, absorbed in stirring the contents. Porta craned over his shoulder, stuffed one or two fairly dry logs into the fire. The thick, globulous mass in the pot heaved itself up in a series of miniature geysers, which exploded and left craters behind them. It smelt rather strong, but that was hardly surprising: we had carted that mess everywhere with us for days past, each of us transporting a share in his water bottle.

‘It has to ferment,’ explained Barcelona, when some of us began to show signs of rebelling.

It had now, it appeared, duly fermented and was ready for distilling. The Legionnaire fixed a tight lid over the cooking pot and Porta set up the distilling apparatus. We sat round in a circle, waiting breathlessly for something to happen.

Our meditations were interrupted by some half-hearted cries of ‘Sieg heil!’ coming from the assembled ranks of the reserve troops.

The visiting lieutenant drove away in an amphibious VW, and Lt. Ohlsen, losing no time, took the newcomers in hand and delivered one of his special pep talks. When at last they were told to fall out they did so almost literally, collapsing to the ground, huddling together beneath the trees in wet, miserable groups. They threw down their equipment and some of them even stretched full length on the soaking grass. I noticed they kept a respectful distance from the rest of us. It was plain that we intimidated them in some way.

Oberfeldwebel Huhn walked across to us and straight through our midst, his step heavy and confident. As he passed by the cooking pot, he caught it with the side of his boot and the whole thing rocked. The Legionnaire managed to set it upright, but not before a few precious drops of liquid had spilled over the side. Huhn glanced down and went on his way without a word of apology. We smelt the newness of his equipment, heard the creaking of his unbroken leather boots as he passed.

The Legionnaire pursed his lips together. He gazed thoughtfully after the retreating Huhn for a few seconds, then turned towards Tiny. Not a word passed between them. But the Legionnaire turned down a thumb, and Tiny nodded.

With his sausage still in his hand, he heaved himself to his feet and marched purposefully after the Oberfeldwebel. His waterproof billowed out behind him, so that he looked rather like a walking barrage balloon.

‘Hey, you!’ he called. ‘You spilt some of our schnaps!’

At the first cry of ‘Hey, you!’, Huhn had gone on walking – evidently never dreaming that anyone of lower rank could dare to address an Oberfeldwebel as ‘Hey you’. But at the mention of the word schnaps he must have realized that it was, indeed, himself that Tiny was accusing. He turned, slowly and incredulously. At the sight of Tiny his jaw sagged and his eyeballs strained at their sockets.

‘What’s got into you?’ he roared. ‘Didn’t anyone ever teach you the right way to address your superiors?’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Tiny, impatiently. ‘I know all that crap. But that’s not what I wanted to talk to you about’

Huhn’s cheeks grew slowly mottled.

‘Have you gone stark starving raving bloody mad?’ he demanded. ‘Do you want me to put you under arrest? Because if not, I advise you to watch your bleeding language! And just try to remember, in future, what it says about it in the HDV.’3

‘I know what it says in the HDV,’ retorted Tiny, imperturbably. ‘I told you once, that’s not what I want to talk about We can discuss it afterwards if it really interests you. But right now I want to talk about our schnaps what you knocked over.’

Huhn breathed deeply and carefully, right down to the bottom of his lungs. And then he breathed out again, with a prolonged whistling sound. Doubtless, in all his seven years of Army service, he had never had a parallel experience. We knew that he had just come from the harsh military camp of Heuberg. Certainly if anyone there had dared to address him as Tiny had just done, he would have shot them out of hand. From the way he kept twitching at his holster, I guessed that he had half a mind to shoot Tiny out of hand. But it was not so easy to get away with it, in front of so many witnesses. A silence had come upon us, and we were all leaning forward, craning our necks for a first-hand view of the affair.

Tiny stood his ground, the sausage still absurdly clenched in his huge paw.

‘You knocked over our schnaps,’ he repeated, obstinately. The least you could have done was apologize, I should’ve thought.’

Huhn opened his mouth. It remained open for several seconds. Then his Adam’s apple bobbed up and down a few times and he closed it again without a word. In its way, the whole scene was quite ludicrous. Even if he hauled Tiny before a court martial, they would almost certainly never believe a word of the indictment. Yet something had to be done. An Oberfeldwebel couldn’t allow a cretinous great oaf of a Stabsgefreiter to stand there insulting him and get away with it.

Tiny jabbed his sausage into Huhn’s chest.

‘Look at it this way,’ he suggested. ‘We’ve been carting that stuff around with us for days now. It’s been everywhere with us. And not a drop wasted, until you came along with your clumsy bleeding boots and went bashing into it. And not so much as a by your leave or a word of apology!’ He shook his head. ‘I don’t know what you’re complaining about, I’m sure. Seems to me it’s us what ought to be complaining, not you. Here we are, minding our own business, brewing up our schnaps—’

Huhn brushed the sausage to one side and took a step towards Tiny, his hand clutching the butt of his automatic.

‘All right, that’ll do! That’s quite enough of that! I’m a patient man, but I’ve had as much as I can take . . . What’s your name? You’ve asked for trouble, and believe me I’m going to see that you get it!’

He pulled out a notebook and pencil and waited expectantly, Tiny just raised two fingers in an unmistakable sign.

‘Get knotted! Your threats don’t mean a damn thing out here. You’re at the front now, remember? And we’re the boys that have survived . . . And you know why we’ve survived? Because we know how to look after ourselves, that’s why . . . And I’m not at all sure that I can say the same for you. In fact, I got a very funny feeling that you ain’t going to see out this particular spell of duty . . . You need a very strong head to survive out here, and I just don’t think you got it . . .’

God knows what would have happened next if Lt. Ohlsen hadn’t intervened and spoilt the fun. It was just getting to the really interesting part when he walked up to Tiny and jerked his thumb over his shoulder.

‘Get lost, Creutzfeldt. At the double, if you don’t want to end up under arrest.’

‘Yes, sir!’

Tiny gave a quick salute, smacked his heels sharply together and left the scene of combat. He came slowly back to the rest of us.

‘I’m going to get that bastard one of these days!’

‘I told you,’ said Heide. ‘I told you we’d have trouble with him.’

‘Don’t you worry.’ Tiny nodded significantly and closed one eye. ‘I got his number. It’s only a matter of time—’

‘For God’s sake!’ burst out the Old Man. ‘You’re going to find yourself in real trouble one of these days if you keep bumping off every NCO you take a dislike to.’

Tiny opened his mouth to reply, but before he could do so there was a wild cry of triumph from the Legionnaire.

‘She blows! Quick, give me the connection! Get a bottle!’

We were at once thrown into a hectic activity. I thrust the rubber tube into the Legionnaire’s outstretched hand, Porta shoved a bottle next to the cooking pot. The apparatus was connected and we watched breathlessly, like children, for the first miraculous signs of distillation. The vapour was already turning into precious drops of liquid.

‘She’s coming!’ yelled Porta.

The excitement was almost unbearable. I felt the saliva collect in my mouth; I suddenly knew a thirst such as I had never known before. Heide ran his tongue round his lips. Tiny swallowed convulsively. Slowly, the bottle began to fill.

All night long we maintained our watch. Bottle after bottle was taken away full of home-brewed schnaps. We forgot all desire for sleep. Lt Ohlsen watched us for a bit, his expression decidedly sceptical.

‘You must be nuts,’ he declared, at last. ‘You’re surely never going to try drinking the vile looking muck?’

‘Why not?’ demanded Tiny, belligerently.

The Lieutenant just looked at him and shook his head.

Lt. Spät also took a fatherly interest in our brewing activities.

‘Aren’t you going to filter it?’ he asked, anx

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...