- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Rumor has it; they are being moved to Warsaw. Heide, who is always informed, claims that all hell is loose over there. There is talk of a German pullback from the eastern frontline. Thousands of British paratroops have landed and Polish soldiers converge on from the woods. But the Polish army is already doomed. Not only by the Reichsführer Himmler in Berlin, but also by Marshal Stalin. The Polish nationalists vainly beg the Red Army for help. But it has already been decided that the Polish communists are to take over Poland. "WITH THIS BRILLIANTLY REALISTIC DRAMA, HASSEL UNCOVERS THE UPRISING OF THE POLISH HOME ARMY" NOUVELLES LITTÉRAIRES, France

Release date: December 23, 2010

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

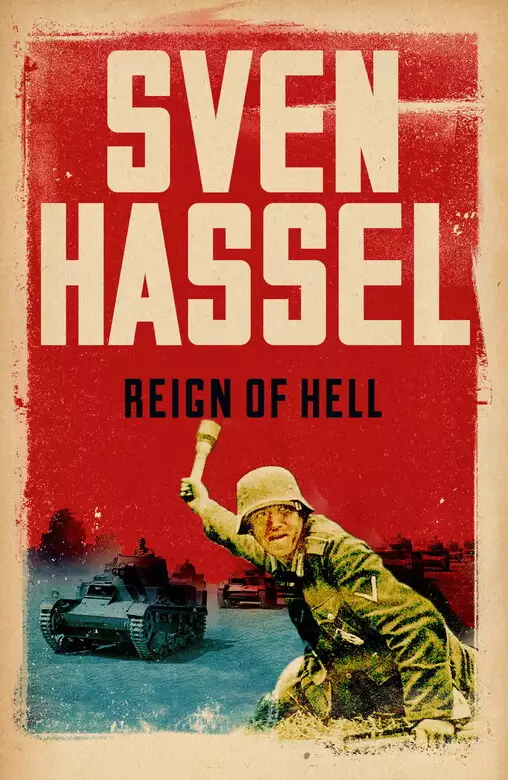

Reign of Hell

Sven Hassel

Why does the waves’ lament, from the dark of the deep abyss, Resound like the sigh of a dying man?

‘From out of the depths of the cold river bed, like a sad dream of death

The song is sung.

From rain-washed fields the silver willows weep in chorus of sorrow . . .

The young girls of Poland have forgotten how to smile.’

‘The Germans are without any doubt marvellous soldiers’—

These words were written in his notebook on 21st May 1940by the future Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke.

This book is dedicated to the Unknown Soldier and to all the victims of the Second World War, in the hope that never again will politicians plunge us into the irresponsible lunacy of mass murder.

‘What we want is power. And we have it, we shall keep it. No one shall wrest it from us’—

Speech by Hitler at Munich, 30th November 1932.

None of the men of the 5th Company wanted to become a guard Sennelager. But what does it matter what a soldier may or may not want? A soldier is a machine. A soldier is there for the sole purpose of executing orders. Let him make only one slip and he would very soon find himself transferred to the infamous punishment battalion, number 999, the general rubbish tip for all offenders.

Examples are legion. Take, for instance, the tank commander who refused to obey an order to burn down a village and all its inhabitants: court martial, reduction to the ranks, Germersheim, 999 . . . The sequence was swift and inevitable.

Or there again, take the SS Obersturmführer who stood out against his transfer to the security branch: court martial, reduction to the ranks, Torgau, 999 . . .

All examples have a certain dreary monotony. The pattern, once established, could never be altered, although after a time they did begin swelling the ranks of the punishment battalions by transferring criminals as well as military offenders.

In Section I, Paragraph 1, of the German Army Regulations can be read the following: ‘Military service is a service of honour’ . . .

And in Paragraph 13: ‘Anyone who receives a prison sentence of more than five months shall be deemed no longer fit for military service and shall henceforth be debarred from serving in any of the armed forces of land, sea or air’ . . .

But in Paragraph 36: ‘In exceptional circumstances Paragraph 13 may be disregarded and men serving prison sentences of more than five months may be enlisted in the Army provided they are sent to special disciplinary companies. Certain of the worst classes of offenders shall be drafted into squads occupied solely with mine disposal or burial duties; such squads not to be supplied with firearms. After six months’ satisfactory service, such men may be transferred to 999 Battalion at Sennelager, along with soldiers who have been charged with offences on the field of battle. In time of war, non-commissioned officers must have spent at least twelve months on active service in the front line; in time of peace, ten years. All officers and non-commissioned officers shall be severely reprimanded if found guilty of showing undue leniency towards the men under their command. Any recruit who endures severe discipline without complaint and shows himself fit for military service may be transferred into an ordinary Army regiment and will there be eligible for promotion in the normal way. Before such transfer shall be approved, however, a man must have been recommended for the Cross on at least four occasions following action in the field.’

The number 999 (the three nines, as it was known) was a joke. Or at any rate, supposed to be joke. It must be admitted that Supreme Command at first totally failed to see the humour of it, for the nine hundreds had always been reserved for the special crack regiments. And then someone kindly explained to them that treble nine was the telephone number of Scotland Yard in London. And what could possibly be more subtle or amusing to the Nazi mind than to give the very same number to a battalion composed entirely of criminals? Supreme Command allowed itself a tight bureaucratic smile and nodded its head in sage approval. Let nine-nine-nine be the number; and just for a bit of further fun, why not preface it with a large V with a red line slashed across it? Signifying: annulled. Cancelled. Wipe out . . . Which could, of course, have referred either to Scotland Yard or the battalion itself. But that was the joke of it. That was what was so excruciatingly funny. Either way, it was enough to make you split your sides laughing. For let’s face it, the swine who served in 999 battalion were scarcely what you could call desirables. Thieves and cut-throats and petty criminals; traitors and cowards and religious maniacs; the lowest scum of the earth and fit only to die.

Those of us sweating our guts out on the front line, didn’t look at it quite like that. We couldn’t afford to. Dukes or dustmen, saints or swindlers, all we cared about was whether a chap would share his last fag with you in times of need. To hell with what a man had done before: it was what he did now, right here and now, that mattered to us. You can’t exist on your own when you’re in the Army. It’s every man for another, and the law of good comradeship takes precedence over all else.

An ancient locomotive grunted slowly up the line, dragging behind it a row of creaking goods wagons.

On the platform, waiting passengers glanced up curiously as the train drew to a halt. In one of the wagons was a party of armed guards, hung about with enough weaponry to wipe out an entire regiment.

We were sitting on one of the departure platforms, playing a game of pontoon with some French and British prisoners of war. Porta and a Scottish sergeant had between them practically cleared the rest of us out, and Tiny and Gregor Martin had for the past hour been gambling on rather dubious credit. The sergeant was already in possession of four of their IOUs.

We were in the middle of a deal when Lieutenant Löwe, our company commander, suddenly broke up the game with one of his crude interruptions.

‘All right, you lads! Come on, look alive, there! Time to get moving!’

Porta flung down his cards in disgust.

‘Bloody marvellous,’ he said, bitterly. ‘Bloody marvellous, ain’t it? No sooner get stuck into a decent game of cards than some stupid sod has to go and start the flaming war up again. It’s enough to make you flaming puke.’

Löwe shot out his arm and pointed a finger at Porta.

‘I’m warning you,’ he said. ‘Any more of your bloody lip and I’ll—’

‘Sir!’ Porta sprang smartly to his feet and saluted. He never could resist having the last word. He’d have talked even the Führer himself to a standstill. ‘Sir,’ he said, earnestly. ‘I’d like you to know that if you find the sound of my voice in any way troublesome I shall be only too happy for the future not to speak unless I am first spoke to.’

Löwe made an irritable clicking noise with his tongue and wisely walked off without further comment. The Old Man rose painfully to his feet and kicked away the upturned bucket on which he had been sitting. He settled his cap on his head and picked up his belt, with the heavy Army revolver in its holster.

‘Second Section, stand by to move off!’

Reluctantly, we shuffled to our feet and looked with distaste at the waiting locomotive and its depressing string of goods wagons. Why couldn’t the enemy have destroyed the wretched thing with their bombs? The prisoners of war, still sprawling at their ease on the ground, laughed up at us.

‘Your country needs you, soldier!’ The Scots sergeant took his half smoked cigarette from his lips and pinched the end between finger and thumb. ‘I’ll not forget you,’ he promised. He waved Tiny’s IOUs in a farewell gesture. ‘I’ll be waiting to greet you when you come back.’

‘You know what?’ said Tiny, without rancour. ‘We should have polished your lot off once and for all at Dunkirk.’

The Sergeant shrugged, amiably.

‘Don’t you worry, mate. There’ll be plenty of other opportunities . . . I’ll reserve a place for you when I get to heaven. We’ll pick up the game where we left off.’

‘Not in heaven we won’t,’ said Tiny. ‘Not bleeding likely!’ He jerked a thumb towards the ground. ‘It’s down there for me, mush! You can go where you like, but you’re not getting me up there to meet St Flaming Peter and his band of bleeding angels!’

The Sergeant just smiled and stuffed the IOUs into his pocket. He took out the Iron Cross which he had won from Tiny and thoughtfully polished it on his tunic.

‘Man, just wait till the Yanks get here! It’ll go down a fair treat . . .’

He held the Cross admiringly before him, in joyous anticipation of the price it would fetch. The Americans were great ones for war souvenirs. There was already a roaring trade in bloodstained bandages and sweaty scraps of uniform. Porta had a large box crammed full with gruesome mementoes, ready for the time when the market would be most favourable. A grisly business, but at least it spelt the beginning of the end as far as the war was concerned.

The locomotive heaved itself and its trail of open wagons to a slow, creaking halt, and we trundled sullenly and resentfully up the platform and into the rain. It had been raining non-stop for four days and by now we were almost resigned to it. We turned up our coat collars and stuck our hands in our pockets and stood with hunched shoulders in a sodden silence. We had recently been issued new uniforms, and the stench of naphthalene was appalling. It could be smelt a mile off on a fine day, and in enclosed quarters it was enough to suffocate you. Fortunately, the lice enjoyed it no more than we did, and they had deserted us en masse in favour of the unsuspecting prisoners of war. So at least we were now saved the trouble of constantly having to take a hand out of a pocket to scratch at some inaccessible part of the body.

Painted on the sides of the leading wagons were the already half-forgotten names of Bergen and Trondheim. The wagons were being used for a transport of sturdy little mountain ponies. We paused for a moment to watch them. They all looked quite absurdly alike, with a dark line along the ridge of the back and soft black muzzles. One of them took a fancy to Tiny and began licking his face like a dog, whereupon Tiny, ever ready to adopt the first animal or child that showed him the least affection, instantly decided that the pony was his own personal property and should henceforth travel everywhere with him. He was attempting to separate it from the rest of the herd and lead it out of the wagon, when a couple of armed guards arrived, waving revolvers and yelling at the top of their voices. Seconds later, the combined noise of apoplectic guards, skittish ponies and a viciously swearing Tiny brought Lieutenant Löwe angrily on to the scene.

‘What the hell’s going on here?’ He pushed the guards out of the way, striding into the midst of the mêlée with Danz, the chief guard at Sennelager and the ugliest brute on earth, striding self-importantly at his elbow. Löwe stopped in amazement at the sight of Tiny and his pony. ‘What the devil do you think you’re doing with that horse?’

‘I’m taking him,’ said Tiny. ‘He wants to be with me. He’s my mascot.’ The pony licked him ecstatically, and Tiny placed a proprietary hand about its neck. ‘He’s called Jacob,’ he said. ‘He won’t be any bother. He can travel about with me from place to place. I reckon he’ll soon take to Army life.’

‘Oh, you do, do you?’ Löwe breathed heavily through dilated nostrils. ‘Put that bloody horse back where it belongs! We’re supposed to be fighting a war, not running a circus!’

He stormed off again, followed by Danz, and Tiny stood scowling after him.

‘Sod the lot of ’em!’ said Porta, cheerfully. He took a hand from his pocket and gesticulated crudely in the direction of Löwe’s departing back. ‘Don’t you worry, mate, they’ll be laughing the other side of their ugly officers’ mugs when this little lot’s over . . . whole bloody lot of ’em, they’ll be for the high jump all right and no mistake.’ He turned and cocked an eyebrow at Julius Heide, who was without any doubt at all the most fanatical NCO in the entire German Army. ‘Don’t you reckon?’ he said.

Heide gave him a cold, repressive frown. He disliked all talk of that nature. It gave him shivers up his rigid Nazi spine.

‘More likely the corporals,’ he said, looking hard at Porta’s stripes. ‘More likely the corporals will find their heads rolling.’

‘Oh yeah?’ jeered Porta. ‘And who’s going to round ’em all up, then? Not the bleeding officers, I can tell you that for a start. How many of us corporals do you reckon there are in this bleeding Army? A damn sight too many to let themselves be put upon, I can tell you that much.’ He poked his finger into the middle of Heide’s chest. ‘You want to get your facts right,’ he said. ‘You want to open your eyes and have a look round some time. The cooking pots are already being put on to boil, mate – and it’s us what’s going to be doing all the cooking, not you and your load of rat-faced officers.’

Heide squared his narrow shoulders.

‘Continue,’ he said, coldly. ‘Go on and hang yourself. I’m making a note of it all.’

Very casually, behind his back, Tiny took a kick at a stray oil drum and lobbed it through the air towards a passing military policeman. The oil drum caught the man on the shoulder, and he spun round in an instant. Silently, Tiny jerked his head towards Heide. The policeman charged forward like a bull elephant. A few years ago, he had probably been directing traffic eight hours a day, out for the blood of parking offenders and careless pedestrians. The war had given him his chance, and now his little moment of glory had come. Before he knew what was happening, Heide found himself up on a charge, with Porta sniggering like a cretin and Tiny droning on and on like a tiresome parrot in the background:

‘I saw it with my own eyes. I saw him do it. I saw him.’

Lieutenant Löwe dismissed the whole affair with a few short sharp words and an irritable wave of the hand.

‘What do you mean, this man attacked you? I don’t believe a word of it. I never heard anything so far-fetched in all my life! Sergeant Heide is an excellent soldier. If he’d attacked you, I can assure you that you would not now be alive to tell the tale . . . Get out of my sight before I lose my temper. Go and find something better to do and stop wasting my time.’ He screwed up the charge sheet, tossed it contemptuously on to the railway line and turned to look at the Old Man. ‘Frankly, I’ve just about had a bellyful of your section today, Sergeant Beier. We are, I would remind you, supposed to be a tank regiment: not a pack of squabbling half-wits. If you can’t keep your men under better control, I shall have to get you transferred elsewhere. Do I make myself quite clear?’

The officer in charge of the convoy which had just arrived now approached the Lieutenant and nonchalantly saluted him with two fingers raised to his cap. He held out a sheaf of papers. He was a busy man. He had a delivery to make – five hundred and thirty prisoners destined for number 999 battalion, Sennelager – and he was anxious to empty the wagons as soon as possible and be on his way. He was already behind schedule, and his next port of call was Dachau, where he had a new load to pick up. Löwe accepted the papers and glanced through them.

‘Any casualties en route?’

The man hunched a shoulder.

‘No way of telling until we get them out and have a look at them . . . We’ve been travelling for almost a fortnight, so one wouldn’t be altogether surprised.’

Löwe raised an eyebrow.

‘Where have they come from?’

‘Just about everywhere. Fuhlsbüttel, Struthof, Torgau, Germersheim . . . The last lot were picked up from Buchenwald and Borge Moor. If you’ll just sign the receipt and let me have it, I’ll be getting on my way.’

‘Sorry,’ said Löwe. ‘Quite out of the question.’ He smiled rather grimly. ‘It’s a habit of mine never to sign a receipt until I’ve checked up on the goods . . . Get the prisoners unloaded and have them lined up on the platform. I’ll take a count of heads. Produce for me the correct number and you can have your receipt. But mind this: I don’t sign for dead bodies.’

The officer pulled an irritable face.

‘Alive or dead, where’s the difference? You can’t be too fussy after five years of war. You want to see the way we make a delivery to the Waffen SS. Short and snappy. No trouble at all. A nice quick bullet through the back of the neck, and Bob’s your uncle! Finished for the day.’

‘Very likely,’ said Löwe, with his top lip curling distastefully. ‘But we are not the Waffen SS. We are a tank regiment and are supposed to be taking delivery of five hundred and thirty volunteers for the front. Dead men are therefore of no possible use to us. You’ll get a receipt for the actual number of live prisoners handed over to my sergeants, and if you wish to raise any objections you are quite at liberty to take matters up with the camp commander, the Count von Gernstein. It is entirely up to you.’

The officer pursed his mouth into a thin line and said nothing. Gernstein was not a man anyone in his right senses would ever choose to take matters up with. Rumour had it that he communed with Satan every night from twelve o’clock till four, and he had a reputation for wanton cruelty and viciousness which struck terror to the heart even after five years of bloodshed and slaughter.

The wagons were opened and they vomited out their load of tortured humanity. The guards stood by with dogs and guns, ready to club senseless the first man who stumbled or fell. One poor devil, palsied and trembling, caught up in the general panic yet not strong enough to keep his footing, disappeared beneath a flood of bodies and emerged at the end of the stampede a bloodied mass, his throat torn open by the snarling hounds.

We stood watching as the trembling figures were lined up in three columns. We saw the dead bodies being tossed back into the wagons. The officer in charge strutted down the columns and briskly saluted Löwe.

‘All present and correct, Lieutenant. I think you’ll find there’s no need to waste time on a roll-call.’

Löwe made no reply. He walked in silence the length of the ragged cortège of men, who had been collected from some of the worst hells on earth and confined in communal suffering for the past fourteen days. He waited while a count was taken. Three hundred and sixty-five men out of the five hundred and thirty who had set out on the journey were still alive.

Löwe stood a moment with bent head. He turned at last to the waiting officer.

‘I will sign for three hundred and sixty-five men,’ he said.

There was a pause. We could feel the tension mounting.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said the officer, through clenched teeth. ‘I believe I have delivered my full quota. The condition of the goods is immaterial. It is the quantity which concerns us.’

Löwe raised an eyebrow.

‘Do we deal in human flesh?’ he said. ‘What is your merchandise? Men or meat?’

Another silence fell. It was broken, none too soon, by the arrival of Gernstein’s aide-de-camp, Captain von Pehl. His car came to a flamboyant halt a few yards away, and the Captain leapt out, smiling benignly upon one and all. He adjusted his monocle and swayed up to the two disputing officers, spurs jingling and gold braid flashing. He clicked his heels together and tapped his polished boots with his riding crop.

‘What news on the Rialto, dear sirs? The end of the war? Or merely another bomb in the Führer’s bunker?’

Gravely, Löwe explained the situation. The Captain brought his riding crop up to his face and thoughtfully scratched his beautifully-shaven chin with it.

‘A slight question of numbers,’ he murmured. ‘One is expecting a battalion, and one receives scarcely three companies. One can understand the predicament.’ He turned pleasantly to the convoy officer. ‘How, if the question is not too impertinent, dear sir, could you possibly manage to mislay so many men?’

He strolled across to the wagon containing the corpses. He inspected for a moment the top layer, then motioned with his riding crop towards one of the bodies. A couple of guards stepped forward and heaved it on to the platform where it lay in a sawdust heap, a dead man without a head. Von Pehl readjusted his monocle. Gingerly, with a handkerchief held to his nose, he bent over the body and examined it. He straightened up and beckoned to the officer.

‘Perhaps you would be so kind as to show me the point of entry of the bullet, dear sir?’

The indignant officer slowly turned crimson. All this absurd amount of fuss over one dead prisoner with a bullet through the back of the head! Did they live in a fool’s paradise, out here at Sennelager?

‘The point of entry,’ gently insisted von Pehl. ‘Purely as a matter of interest, I assure you.’

Behind von Pehl stood his ordnance officer, Lieutenant Althaus, with a sub-machine-gun under his arm. Behind Althaus stood a lieutenant of the military police, rocklike and immovable. They were mad, of course. They were all mad. No one in his right mind would have made such a song and dance over one dead prisoner. One dead prisoner, a hundred dead prisoners, what the devil did it matter? There were plenty more where that lot had come from.

‘There was a revolt.’ The officer tilted his chin, in sullen defiance. ‘There was a revolt. The guards had to fire.’

Von Pehl stretched out a languid hand.

‘Report?’

‘I – I haven’t had time to write one out yet.’

Von Pehl tapped his teeth with the handle of his riding crop.

‘So tell me, dear sir – where, exactly, did this – ah – revolt take place?’

‘Just outside Eisenach.’

Eisenach.

It was far enough away, in all conscience. Perhaps now the man would stop poking his interfering Prussian nose into other people’s business and let him get on his way to Dachau for the next batch of human misery.

‘You know, my dear sir,’ murmured von Pehl, ‘that the regulations quite plainly state that any such incident as the one you have mentioned should be reported immediately? Without fail? No matter what?’ He turned to Althaus, standing at his shoulder. ‘Lieutenant, perhaps you would be so good as to telephone at once to the station master at Eisenach?’

We stood patiently waiting in the rain, while von Pehl amused himself by walking up and down looking like a mannequin with a hand on his hip, jangling his spurs and tapping himself with his crop. The officer of the convoy ran a finger round the inside of his collar. Discreetly, his men began to edge away from him. One of the guards, finding himself at my side, spat on the floor and spoke to me out of the side of his mouth.

‘I always said he was riding for a fall. Over and over again I’ve said it. The way he treats those prisoners is disgraceful. Absolutely bloody disgraceful. I’ve said so all along.’

Lieutenant Althaus returned, accompanied by the station master, a small squat man wearing a steel helmet just in case things should turn nasty. He held out a jovial plump hand, which von Pehl adroitly managed not to notice without giving any offence. The convoy officer made a rasping sound in the back of his throat.

‘I trust Colonel von Gernstein is keeping well?’ he said.

His attempt at polite conversation fell into a void of stony silence. The station master dropped his hand to his side. Lieutenant Althaus fingered his sub-machine-gun. Von Pehl examined his filbert fingernails. The convoy officer took a step backwards. He should have remained where he belonged, in Budapest, in the Hungarian Army. It was a dangerous game he was playing, gambling on fame and fortune in Nazi Germany.

Von Pehl turned casually to his aide.

‘Well, Lieutenant? What news from Eisenach?’

Eisenach, it seemed, not only had no knowledge of the alleged revolt: they had not even heard of the convoy. I saw a frosty sparkle appear in von Pehl’s cold Prussian eyes. He beckoned to Danz, who charged up like an eager rhinoceros. The Hungarian was arrested on the spot on charges of murder, submitting a false report and sabotaging a convoy. He was promptly manhandled into a waiting truck and driven off to Sennelager. Lieutenant Löwe duly signed a receipt for the delivery of three hundred and sixty-five volunteers, and the guards, cowed and nervous since the arrest of their officer, withdrew in some disorder. Von Pehl unscrewed his monocle, nodded affably at the assembled volunteers, gave himself one last hearty thwack with his riding crop and mercifully disappeared.

Relief was instantaneous. The tension went out of the atmosphere, cigarettes were lighted, men breathed more easily. Some of the MPs even went so far as to pass round bottles of booze they had recently brought back from France with them, and under the comfortable influence of alcohol we all became blood brothers and rolled off arm in arm to the station canteen to drink each other’s health.

The prisoners were given permission to sit down, and some food was passed out. Only dry bread. But even dry bread can be a luxury to a man who has seen the inside of Torgau or Glatz – to anyone who has lived for days on a diet of water in the dark hell of Germersheim, where more people go in than have ever come out.

Germersheim . . . It’s a name that con. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...