- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

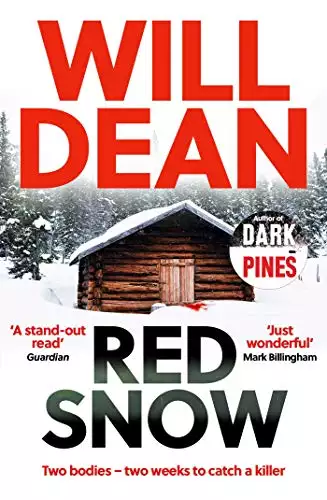

Longlisted for the Theakston Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year Award, 2020 Red Snow is the eagerly awaited follow-up to Dark Pines, selected for ITV's Zoe Ball Book Club TWO BODIES One suicide. One cold-blooded murder. Are they connected? And who’s really pulling the strings in the small Swedish town of Gavrik? TWO COINS Black Grimberg liquorice coins cover the murdered man's eyes. The hashtag #Ferryman starts to trend as local people stock up on ammunition. TWO WEEKS Tuva Moodyson, deaf reporter at the local paper, has a fortnight to investigate the deaths before she starts her new job in the south. A blizzard moves in. Residents, already terrified, feel increasingly cut-off. Tuva must go deep inside the Grimberg factory to stop the killer before she leaves town for good. But who’s to say the Ferryman will let her go?

Release date: January 10, 2019

Publisher: Oneworld Publications

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Red Snow

Will Dean

To my agent, Kate Burke: thank you for your energy and wisdom. You’re the best.

To the team at Northbank Talent: thank you all for your backing and passion.

To my editor, Jenny Parrott: thank you for your belief, enthusiasm, and brilliance.

To the rest of the team at Oneworld and Point Blank: thank you for being so fantastic. Thanks to Juliet, Novin, Harriet, Margot, Thanhmai, Cat, Mark, Emily, Aimee, James, Paul and the whole team. I could not ask for a more excellent publisher.

To Mark Swan and James: thanks for the beautiful covers.

To all the bloggers and booksellers and reviewers and early supporters and tweeters and fellow authors: thank you for your enthusiasm and time. Readers benefit so much from your recommendations and insight. I am one of them. Special thanks to Liz Barnsley, Nina Pottell, Leilah Skelton, Sam Missingham, Isabelle Broom, Ali Karim, Mike Stotter, Abby (Crime by the book), Mart, Kate (The Quiet Knitter), Gemma Wiles, Ellen Devonport (and Bibliophile BC), Tracy Fenton (and all of TBC), Helen Boyce, Tripfiction, Mary Picken, Janet Emson, Jen Lucas, The Booktrail, Noelle Holten, Ayo Onatade, John Fish, Anne Cater, Abby Slater, Candice Sawchuk, Laura Rash, The Average Reader (Mrs Bloggs) and Dan Stubbings.

To Hayley Webster, Bethany Rutter and Alice Slater: thank you for early incisive comments and for all your warmth and wisdom.

To @DeafGirly: thank you so much for your expert feedback, and your support. In many ways your opinion matters to me more than anyone else’s. I will be forever grateful.

To the Zoe Ball Book Club: thank you so much for everything.

To Val McDermid: thanks for choosing me as part of your New Blood panel at Harrogate. It was one of the best experiences of my life.

To Swedish nature: thank you for making me feel like a kid in a candy store. Thanks for surprising me. Thanks for stunning seasons (and for all the moose).

To my family, and especially my parents: once again, thank you for letting me play alone for hours as a child. Thank you for letting me read and make up strange stories. Thank you for allowing me to be bored. It was a special gift.

To my friends: apologies if I’ve missed (even more) bonfires and lunches due to rewriting. Thank you all for being wonderful.

Special thanks to my grandma and my late great-grandma. I loved writing Cici and that’s partly because she’s inspired by you both.

To my sister: thank you for reading Dark Pines and thanks for telling me it got you back into reading. That meant the world to me.

To my wife and son: thank you. Love you. Always.

Chapter 1

There’s a Volvo down in the ditch and I’d say it’s been there a while.

I touch the brakes and my truck comes to a stop nice and easy; studded tyres biting into ice and bringing me to a silent standstill. It’s all silent up here. White and utterly, utterly silent.

The display on my dash reads minus nineteen Celsius. I pull on my hat and move the earflaps so they don’t mess with my hearing aids and then I turn up the heat and leave the engine idling and open my door and step down.

The Volvo looks like an ice cube, all straight lines and sparkling crystals, no signs of life, not a colour or a feature to look at. It’s leaning down hard to the right so I’m roughly level with the driver’s side window. I knock. My gloved knuckle sounds dull on the frosted glass so I rub my hand over the window but it’s blasted solid with ice.

I step back, cold air burning my dried-out cheeks. Need more creams, better creams, prescription winter-creams. My mobile has no reception here so I look around and then head back to my pick-up and grab my scraper, one from a collection of three, you can never be too careful, from my Hilux door well.

As I scrape the Volvo window the noise hits my aids like the sound of scaffolding poles being chewed by a log chipper. I start to get through, jagged ice shards spraying this way and that. And then I see his face.

I scrape harder. Faster.

‘Can you hear me?’ I yell. ‘Are you okay?’

But he is not okay.

I can see the frost on his moustache and the solid ice flows running down from each nostril. He is dead still.

I keep scraping and pull the door handle but it’s either locked or frozen solid or both. My breath looks nervous in front of my face; clouds of vapour between me and him, between my cheap mascara and his crystallised eyelashes. I’ve seen enough death these past six months, more than enough. I knock on the glass again and strain at the door handle. And then his eyes snap open.

I pull back, my thick rubber soles losing purchase on the shiny white beneath.

He doesn’t move. He just looks.

‘Are you okay?’ I ask.

He stares at me. His body is perfectly still, his head unmoving, but his grey-blue eyes are on me, searching, asking questions. And then he sniffs and shakes his head and nods a kind of passive-aggressive ‘thanks but I got this’ dismissal which is frankly ridiculous.

‘My name’s Tuva Moodyson. Let me drive you into Gavrik. Let me call someone for you.’

The frozen snot in his moustache creaks and splinters and he mouths, ‘I’m fine’ and I can read his lips pretty well, over twenty years of practice.

I pull on his door handle, my neck getting hot, and then it starts to give so I pull harder and the ice cracks and the door swings up a little. It’s heavy at this angle.

‘You trying to snap my cables?’ he says.

‘Sorry?’

‘It’s about minus twenty out here I’d say and you just yanked my door open like it’s a treasure chest. Best way to break a door handle cable.’

‘You want to warm up in my truck?’ I say. ‘I can call breakdown?’

He looks out toward my truck like he’s deciding if it’s a suitable vehicle to save his life and I look at him and at the layers of clothes he’s entombed himself in: a jacket that must contain five or six other jackets judging by its bulk, and blankets over his knees and thick ski gloves and I can see three hats, all different colours.

He coughs and spits and then says, ‘I’ll come over just to warm up, just for a minute.’

Well, thanks for doing me that favour mister Värmland charm champion.

I help him out and he’s smaller than me, half a head smaller, and he’s about fifty-five. There’s a pair of nail scissors on the passenger seat next to a carrier bag full of canisters, and there’s a bag of dry dog food in the footwell. He locks his Volvo like there are gangs of Swedes out here just waiting to steal his broken down piece of shit car, and then he trudges over to my pick-up truck.

‘Japanese?’ he says, opening the passenger side.

I nod and climb in.

‘Ten minutes and I’ll be out your hair,’ he says.

‘What’s your name?’

He coughs. ‘Andersson.’

‘Well, Mr Andersson, I’m Tuva Moodyson. Nice to meet you.’

We look out of the windscreen for a while, side by side, no talking, just staring at the white of Gavrik Kommun. Looks like one of those lucky blanks you get in a game of scrabble.

‘You that one that writes stories in the newspaper?’ he says.

‘I am.’

‘Best be heading back to my car now.’

‘If you go out there again you’re gonna end up dead. Let me drive you into town, your car will be fine.’

He looks at me like I’m nine years old.

‘I’ve driven more tough winters than you’ve had hot lunches.’

What the hell does that even mean?

‘And I can tell you,’ he says, rubbing his nose on his coat sleeve. ‘This ain’t nothing. Minus twenty, maybe twenty-two, it ain’t nothing. Anyhows, I texted my middle boy three hours ago, told him my location, and when he’s done up at the pulp mill he’ll come pick me up. You think I ain’t spent time in ditches in winter?’

‘Fine. Go,’ I say, pausing for him to think. ‘But I’ll call the police and then Constable Thord’ll have to come by and pick you up. How about we save him the bother.’

Mr Andersson sighs and chews his lower lip. The ice on his face is thawing, and now he just looks flushed and gaunt and a little tired.

‘You gonna be the one driving?’ he says.

I sigh-laugh.

He sniffs and wipes the thawed snot from his moustache whiskers. ‘Guess I don’t got much choice.’

I start the engine and turn on both heated seats. As we pass his frozen Volvo he looks mournfully out the window like he’s leaving the love of his life on some movie railway platform.

‘Why don’t you buy Swedish?’ he asks.

‘You don’t like my Hilux?’

‘Ain’t Swedish.’

‘But it goes.’

We drive on and then he starts squirming in his seat like he’s dropped something.

‘My seat hot?’ he says.

‘You want me to switch it down a notch?’

‘Want you to switch the damn thing off cos I feel like I peed my pants over here.’ He looks disgusted. ‘Goddam Japanese think of everything.’

Okay, so I’ve got a racist bore for a passenger but it’s only twenty minutes into Gavrik town. It’s never the cute funny smart people who need picking up now, is it?

‘Where do you want dropping off, Mr Andersson? Where do you live?’

‘Just drop me by the factory.’

‘You work there?’

‘Could say that. Senior Janitor. Thirty-three years next June.’

I pull a lever and spray my windscreen and the smell of chemical antifreeze wafts back through the heating vents.

‘How many janitors they got up there?’ I ask.

‘Just got me.’

‘You get free liquorice?’

‘I ain’t got none so don’t go asking. I’m the janitor and that’s it.’

I drive up to an intersection where the road cuts a cross-country ski trail marked with plastic yellow sticks and they look like toothpicks driven into a perfect wedding cake. The air is still and the sky’s a hanging world of snow and it is heavy, just waiting to dump.

‘You did the Medusa story, eh?’

I nod.

He shakes his head.

‘You just about ruined this place, you know that? Good few people be quite pleased to see you run out of town, I’m just saying what I heard.’

I get this bullshit from time to time. As the sole full-time reporter here in Gavrik, I get blamed for bad news even though I’m just the one writing it.

‘I’d say it was a job well done,’ I say.

‘Well, you would, you done it.’

‘You’d rather elk hunters were still getting shot out in the woods?’ He goes quiet for a while and I switch the heat from leg/face to windscreen.

‘All I know is we lost some hard-won reputation,’ he says. ‘And thank God we still got the factory and the mill to keep some stability. That’s all I’m saying and now I done said it.’

As I get closer to town, the streets get a little clearer, more snowploughing here, more yard shovelling, and the municipal lighting’s coming on; 3pm and the streetlights are coming on. Welcome to February.

‘Suppose you were just doing your job like anyone but we’re a small town and we’re cut off from everywhere else so we’ve learned to stick together. I got eight grandkiddies to worry about. You’d know if you were from these parts.’

I drive on.

The twin chimneys of the factory, the largest employer in town, loom ahead of me. It’s the biggest building around here save for the ICA Maxi supermarket. Two brick verticals backdropped by a white sheet.

‘Say, you hear me pretty good for a deaf person, don’t mind me saying.’

‘I can hear you just fine.’

‘You using them hearing aid contraptions?’

I feel his eyes on my head, his gaze boring into me.

‘I am.’

‘I’ll be needing them myself pretty soon, sixty-one this coming spring.’

I drive past the ice hockey rink and on between the supermarket and McDonald’s, the two gateposts of Gavrik, and up along Storgatan, the main street in town. I head past the haberdashery and the gun shop and my office with its lame-ass Christmas decorations still in the window, and on toward the cop shop, and then I pull up next to the Grimberg Liquorice factory ‘Established 1839’ – or so it says on the gates.

‘This okay?’ I ask.

He gets out without saying a word and I look around and there are five or six people scattered about all looking up to the sky. This doesn’t happen, especially in February. A hunched figure in a brown coat slips on the ice as he walks away. I try to look up through the windscreen but it’s frosted at the top, so I open my door and climb out onto the gritted salted pavement. I can hear mutterings and I can sense others joining us from Eriksgatan.

They’re looking up at the right chimney, the one I’ve never seen smoke coming out of. There’s a man, or I think it’s a man, a figure in a suit climbing the ladder that’s bolted to the side of the chimney, climbing higher and higher past the masts and phone antennas attached to the bricks. He’s in a hurry. No hat or gloves. I look up and the sky is blinding white, dazzling, and the pale clouds are moving fast overhead, the wind picking up. As I stare up it’s like an optical illusion, like the chimneys are toppling over onto me. And then the man jumps.

Chapter 10

This will be my last big Gavrik story and I might just have found a way in.

‘I can help,’ I say eagerly, the offer crystallising and clarifying in my head as the words pass my lips.

‘I don’t see how.’

I take a sip of the wine and the oven beeps again so he excuses himself and clears our bowls, mine with three complete tongues, the largest three, hidden deftly beneath a romaine lettuce leaf. He pulls on a pair of thin latex gloves, the transparent kind, I can see his knuckle hair through them, and gets to work with his knife.

Holmqvist brings over two hot plates of ox tongue, his hand protected by a tea towel, and places them down. Mine is sliced thinly and covered in jus and sprinkled with flat-leaf parsley and sea-salt crystals. His is whole.

‘Where were we,’ he says, savouring his meal, sticky taste-buds clearly visible on the top of his whole tongue like the nubs of some hideous Lego brick.

‘I can help you,’ I say again.

‘No, sorry. I work alone. I don’t think anyone can help me except the Grimberg women. I’ll have to keep pushing.’

‘The more you push the more they’ll push back,’ I say.

‘We have a contract,’ he says.

‘They’ll give you the bare minimum, then. The book will be dull.’

He looks agitated now, squirming on his chair and scratching the back of his hand.

‘Let me talk to them,’ I say, and he’s shaking his head before I’ve even finished the sentence.

‘What makes you think . . .’

‘It’s what I do,’ I say. ‘Let me talk to them. Listen to them.’

He squirms and scratches the palms of his hands. ‘But I have a routine, a ritual. I can’t write with another person. I write alone. Always have.’

‘You still can,’ I say, working out the details in my head. ‘I’ll research for you. Freelance. I’ll give you all my research notes. You pay me. You write the book.’

‘A short-term research contract?’

‘Exactly.’

He scratches his neck and then his ears.

‘So, in return for you interviewing the three remaining Grimbergs – Cecilia, Anna-Britta and young Karin – I would, rather, my publisher would, pay you?’

I nod.

‘I’d have to talk to my editor.’

‘Twenty-thousand kronor,’ I say. ‘Up front.’ I feel like a movie gangster but really I need to uncover if Gustav had enemies, anyone with enough leverage to force him to make that fatal jump.

‘I’ll have to check,’ he says.

‘I’m leaving town soon,’ I say. ‘And I am good, David. Very good. I can start on this right away. I’d work on it alongside my Posten reporting. And I’ll work in the evenings.’

He chews on his lip and looks at me and then looks up at the ceiling and then looks at me again.

‘Twenty-thousand kronor,’ he says. ‘Half on completion of the interviews. Half on publication.’

‘All up front,’ I say.

‘Take it or leave it,’ he says, half filling my glass with red wine.

I feel hot in my socks. This is my way in.

‘I’ll take it,’ I say.

He looks at my plate. ‘Excellent. Now, eat up, it’s getting cold. Bon appétit.’

I have one week left in Toytown and I still have to move out and return my truck and attend a ‘surprise’ leaving party at Ronnie’s Bar, and I have to complete a final print for the Posten, one I can be proud of. This time it’ll be fixed Friday and distributed Saturday. Only the second time it’s ever happened. Industrial action at the printers in Gothenburg; they’re striking over working hours. Good for them. Now I’ll need to juggle all that with researching Holmqvist’s book but at least I can ask the Grimbergs about Gustav’s jump. I can dig.

‘I’ll do a good job,’ I say, but he’s lost in the art of slicing through his slab of tongue. It’s black at the licking end and thick and pink at the throat end and it looks as tough as a saddle. I drink a little of his red wine and keep it in my mouth and then I fork in a thin slice of bull tongue. Tastes a bit like rare, fillet steak, at least when it’s masked by wine. I chew and then hesitate, my throat asking me if this is something I really want to swallow, and then I force it down.

‘After what we went through with Medusa and all, I trust your instincts,’ he says. ‘I’m not liked in this town, everyone thinks I’m strange and really I don’t much care anymore as long as I can write up here in peace, but I do take this project very seriously indeed. I’m putting my faith in you.’

I’m flattered.

‘Email me your bank details so I can prepare the transfer.’

He takes a business card from his pocket and slides it across the table to me.

‘Do I get a deadline?’ I ask.

His upper lip bulges as his tongue moves up over his top teeth.

‘Next Sunday.’

That suits me because after that I’ll be living in a hotel by the sea overlooking a clear horizon, near a city with an art gallery and excellent Indian and Lebanese food and a department store and a decent airport. I’ll be waiting to move into a nice little apartment and I’ll have already paid the first month’s rent.

He has a thick wedge of tongue on his fork, the taste buds glistening with sauce, and he places it back down on his plate.

‘The Grimberg women don’t like me,’ he says with a wry laugh.

‘They’re mourning,’ I say. ‘Their world has shattered.’

‘They need this deal, Tuva. And so do I. You should also speak with the janitor and a few other long-serving employees, they don’t open up to me either, and then submit your typed notes and we can all walk away happy.’

‘I’ll do my best.’

He smiles and rolls up his sleeves and my God this man is half ape. He clears away the plates of tongue and I’m relieved, my stomach unclenching at the prospect of dessert. You can’t serve offal for dessert, not even he would do it.

‘Raspberries, basil, cracked black pepper and vanilla mascarpone.’

He says mascarpone like it rhymes with Al Capone and I snatch the plate from his hand greedily, happy for something to enjoy rather than endure.

‘How was your Christmas, Tuva?’

‘Didn’t celebrate,’ I say, images of Mum’s grave in my mind, candleless, weeds working their way up from deep underneath the snow and earth. I think back to the fish fingers I ate for Christmas lunch in front of the TV. Then in bed. Bottle of vodka. No glass. The fish fingers coming back up. The dread that I didn’t do enough for her, that I was the one person that could have let her go with a kind word in her ear and I did not. I could’ve whispered, ‘don’t worry Mum’ or even just, ‘I’m here, it’s okay’ but I did not.

‘Wasn’t in the mood,’ I say.

‘It was a horrible end to the year,’ he says, misunderstanding me, thinking I was talking about Medusa. ‘I couldn’t have written such a thing.’ He downs the remainder of his wine. ‘I don’t celebrate either, never do.’

‘What are they like?’ I ask.

‘The Grimbergs?’

I nod.

‘They’re intriguing, I must say. Kind of quasi-aristocratic and incredibly superstitious, well-read, and that means a lot coming from me. They’re all bright, hard-working, stoic to the point of I don’t-know-what. You might need to spend hours and hours with them to gain their trust.’

‘Actually the biggest story for the Posten is Gustav’s suicide, ‘I say, ‘so I’ll need to interview them for that. Kill two birds.’

‘Ah,’ he says, his eyes pained.

‘What?’

‘Don’t call it a suicide when you talk to them, call it “the accident” or “the tragedy” or something like that. They don’t think like you and me.’

I don’t think like you, mate. I don’t know anyone who does.

‘Fine,’ I say.

He smiles an arrogant smile and clears away our dessert bowls; mine wiped clean, his hardly touched.

‘Are they tempted to sell the factory now Gustav’s dead?’

‘The vultures are circling,’ he says. ‘That lawyer with the stoop and the sculpted face, the one with all the real estate, he’s very interested, well he would be wouldn’t he? Now that my lawyer’s retired, Hellbom has the whole town to himself. A monopoly. And what with his wife working there, they could modernise and make a fortune. But the Grimbergs won’t sell. Over their dead bodies. And this book deal should help them keep the place in business.’

He stretches an arm out to me over the table.

‘Glad to work with you,’ he says.

I reach out tentatively to meet his grasp, his knuckles sliding next to mine. ‘Same,’ I say.

I pull on my outdoor gear, happy for the unexpected and very much needed twenty-thousand kronor and imagining my next apartment, maybe one with a partial sea-view and a washing machine. Then my hearing aid beeps a battery warning and I rattle my key fob, two spare batteries in there, I never go anywhere without them. I say goodbye and drive away. I stuck to my one glass limit and that feels pretty good. Every evening is a test and I passed this one with flying colours. I drive by the sisters’ woodsmoke and head slowly down the hill and as I pass Viggo’s cottage I notice lights and exhaust fumes in my rear-view mirror and his Volvo pulls out onto the track and follows me.

Chapter 11

Viggo’s on a job, that’s all, maybe taking someone to Karlstad Central Hospital or to Ronnie’s Bar. Big deal. But I accelerate and switch my lights to full and look at my phone because it might be a big deal with this creep, it just might be. He locked me in the back of his taxi once before and scared the colour right out of me.

I’m sweating.

Cold sweat, chills under my sleeves and up my calves. Nobody else around. Empty roads. My mirrors are bright with his headlights and he’s too close to my rear bumper. Nobody drives like this on snow, not even on a ploughed asphalt road. If I brake he will hit me. So I accelerate, opening up a small gap, but then I see the bend near Bengt’s place and slowly tap my brake, pumping it gently, partly to show the shithead behind that I’m slowing down, and partly to keep a grip on this ice. I skid little skids but I steer out of them and the carved tracks help me to stay on the road. I make the turn and carry on at about fifty kph and then indicate and turn left and judder up onto the main road and accelerate like hell.

He’s still following me.

The gap’s closing.

Why wouldn’t he be driving this way, there’s nothing in the other direction, just an empty road leading to a junkyard and then Spindelberg prison. But the distance between us is too small. Unsafe. I spray antifreeze on my rear windscreen and turn my heated seat to low, sweat beading on my neck and my upper lip. I can make out his face and his sallow grey eyes. He turns his headlights to full beam and they flash in my rear-view mirror and now I can’t see him back there. I wipe the rear screen and he’s coming faster now, no one else on the road. I can feel him behind me, his bumper, my nerves on edge, his Volvo right there, with its ‘Kids on Board’ safety sign erect on the roof. He dips his headlights and starts flashing his hazards. What the hell is that, some sort of message? Some sort of Nordic distance flirting? My heart races and I put my foot down and nudge one ten which is way too fast on this road.

He dips his beams and switches his interior lights on and I can clearly see his grey, pallid face and I can see the objects hanging from his rear-view mirror. I can’t make out detail but I remember from before. A thumb-sized hustomte troll. A crucifix. And a Swiss army knife.

I head under the underpass, my hands tight on the steering wheel, my body stiff, my mind as focussed as it can be; the taste of hot dead tongue still lingering on my warm live tongue. And then he turns up and off without indicating and joins the E16 northbound, toward the pulp mill. He’s gone. Of course he didn’t indicate. The worst men don’t indicate. Ever. It’s like they feel entitled to turn whenever they feel like it.

I breathe and slow down to sixty.

Seven days, Tuva. Seven days and then out of this place for good. I slump in my seat and rub my eyes. I grab the pack of wine gums on the passenger seat and squeeze it with my hand until it bursts and then I take three and put them in my mouth to get rid of the bull taste.

The colours outside change. It was all white in the woods, all unbothered snow and clear ice-streams, motionless over granite. Here, approaching town, the white picked out by my headlights is grey from exhaust fumes and grit and salt and boot prints, and the colour, what colour there is, is man-made and uncoordinated; bright jarring flashes of windproof sportswear and kid’s sledges.

I pass between ICA Maxi and McDonald’s and I’m starting to wonder if I’m getting paranoid here in my last week. The chimney suicide unsettled me. And Viggo Svensson was on a job, an urgent pick-up, and he drove from his house to the motorway. That’s all.

I could do with a puritanical cocoa-only smug month and maybe I’ll do that in March. Or April.

When I park I take the bottle of water from my truck because it’ll burst if I just leave it there, and head upstairs to my apartment. There are three empty black suitcases in my living room next to my PlayStation. One’s old and I bought the other two in Karlstad for the move. Straightforward. That’s my life. No pets, no relationships, no furniture, no heirlooms, no plants. No living things whatsoever.

I unpeel one of those sheet face-masks. This one’s peppermint and I reckon I could do with about six consecutive treatments. Just fucking wallpaper me. I look like a horror movie but my skin’s hurting which means it’s getting a drink. I pull out my aids and pour three fingers of white rum and check the headlines on my iPad. Police ask drivers to be prepared and have a phone and blankets when they travel. Goddam February. Living here is like living in Siberia except our broadband’s ten times faster.

I sleep an agitated sleep and wake up and turn off my pillow alarm. Holmqvist asked me to meet him under the factory arch at 9am and that’s where he is when I drive past at 8:55. I park at my office and walk over to him standing right there in Gustav’s death spot. Right there.

‘Morning,’ he says.

‘Morning,’ I say, not wanting to get too close.

He moves away from the arch and he’s got a confidence I haven’t seen before, like he’s guiding me around a show-home and he’s ready to sell it to me, like he’s prepared his spiel and he’s pretty happy with his product.

‘Look from back here,’ he says, gesturing to the railings, razor burns raw under his chin. ‘Better view.’

We stand with our arctic coats resting against the iron railings, looking up at the building.

‘Let’s start with the basics. Built in 1839 from local brick, the tallest non-ecclesiastical structure in Värmland, outside of Karlstad of course, for ninety-seven years. Seven men died during construction. The scaffolding failed.’ He looks up at the chimneys and then back down to the archway. ‘Most of the site is deconsecrated land.’

‘Sorry?’ I say.

‘It was church land before, belonged to St Olov’s.’ He points to the ruined church and then back to the factory. ‘There are graves underneath us, hundreds of ancient tombs. What you can see here used to be the factory in its entirety. The ground floor left of the arch was the cooling and stamping rooms, and the furnace under the chimney to heat that part of the building. Used to be that the right side of the arch, ground floor, was the shredding and mixing and heating area, big vats of sugar syrup, and a furnace there under that chimney.’

I stare at the death chimney.

‘Nowadays all the manufacturing goes on at the corrugated-steel structure at the rear left, behind the old stamping rooms, which are now in fact the canteen, you following?’

‘I think so.’

‘Upstairs hasn’t really changed. Left of the arch: the offices and archives. Over the arch: the Receiving Room, you’ll be working from there mostly. To the right of the arch is the most luxurious part of the whole building: the residence. Which includes the “Grand Room”. I hope you’ll get access, someone needs to.’

‘You haven’t been inside?’

‘Follow me.’

He walks to the arch and I do as he says. It’s not swine cold today, just about minus-seven cold. It is discomfort-chilblain cold not death cold.

‘This way,’ he says, pointing to the staircase I saw after the burial.

I follow him up the stone risers with their red carpet runn

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...