- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

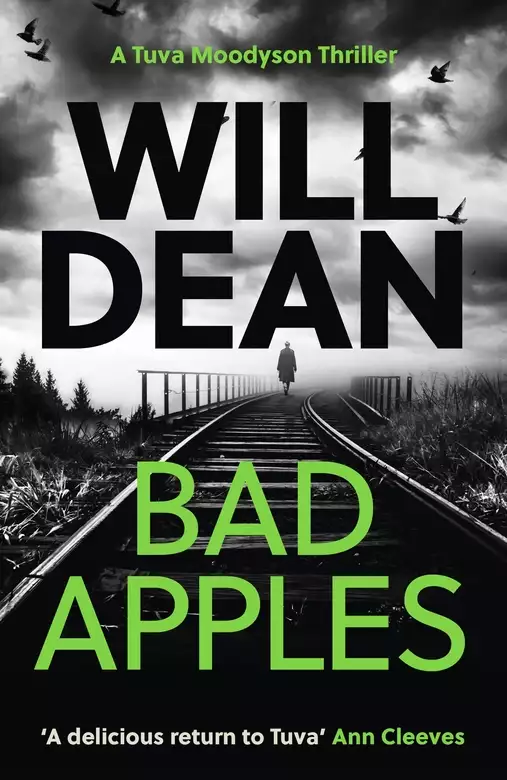

Synopsis

Book 4 in the Tuva Moodyson series.

It only takes one...

A murder

A resident of small-town Visberg is found decapitated

A festival

A grim celebration in a cultish hilltop community after the apple harvest

A race against time

As Visberg closes ranks to keep its deadly secrets, there could not be a worse time for Tuva Moodyson to arrive as deputy editor of the local newspaper. Powerful forces are at play and no one dares speak out. But Tuva senses the story of her career, unaware that perhaps she is the story...

(P) 2021 Audible Ltd.

Release date: May 1, 2023

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Bad Apples

Will Dean

To my literary agent Kate Burke, and the team at Blake Friedmann: thank you.

To my editor Jenny Parrott, and the team at Oneworld: thank you.

To my international publishers, editors, translators: thank you.

To Maya Lindh (the voice of Tuva): thank you.

To all the booksellers and bloggers and reviewers and early supporters and tweeters and fellow authors: thank you. Readers benefit so much from your recommendations and enthusiasm. I am one of them. Special thanks to every single reader who takes the time to leave a review somewhere online. Those reviews help readers to find books. Thank you.

To @DeafGirly: thank you once again for your help and support. In many ways your opinion matters to me more than anyone else’s. I continue to be extremely grateful.

To Sweden: what a place! Thanks for welcoming me in.

To my family, and especially my parents: once again, thank you for letting me play alone for hours as a child. Thank you for taking me to libraries. Thank you for letting me read and draw and daydream and scribble down strange stories. Thanks for not censoring my book choices (too much). Thank you for allowing me to be bored. It was a special gift.

To my friends: thanks for your ongoing support (and patience, and love).

To Mary Shelley and Irvine Welsh: I read Frankenstein and Trainspotting back-to-back as an awkward teenager. The books blew my mind. Thank you.

Special thanks to my late granddad for teaching me some valuable lessons. He taught me to treat everyone equally, and with respect. To give the benefit of the doubt. To listen to advice even if you don’t then follow it. To take pleasure from the small things in life. To read widely. To never judge or look down on anyone. To be kind. To spend time with loved ones. To keep the kid inside you alive.

To Bernie and Monty: what can I say? I’m lucky. You both make me happy. Thank you.

To every shy, socially awkward kid: I see you. I was you. It will get easier. I promise.

To my wife and son: Thank you. Love you. Always.

Chapter 1

I slam my foot on the brakes and come to a halt a metre behind the black car.

My Hilux shakes on its axels.

Thick fog.

My seatbelt digs in. The 4x4 in front has its hazard lights flashing. Wisps of fog drift between my bonnet and its rear end, illuminated by my headlights. Is the driver in trouble? I open my window a crack and mist pours in like smoke billowing around a closed door. Why would you stop your car on this hillside road? It hasn’t broken down, the exhaust fumes are drifting out into the forest air.

I switch on my hazard lights and that’s when I hear the scream.

Then another scream. Fainter. Or perhaps just an echo.

My head jolts to the left, to the dense pines hidden by the fog. Sweat starts to drip down my back. I check my phone. Good reception. Another scream, this one weaker: lost to the mists.

Did the driver in front leave the relative safety of their car to wander through the trees?

As I open my door to get out, the 4x4 in front jerks back and its rear lights shine bright in my face. I fall onto wet ground, my hands sinking into leaf sludge. Are they reversing into me? I scramble to my feet.

‘Hey!’ I yell.

The black car has rolled back a little because of the steepness of Visberg hill, that’s all. More like a mountain than a hill. Almost a cliff. The car gains traction and its tyres squeal as it accelerates hard and disappears uphill into the murk.

My heart’s thumping.

Cold air and exhaust fumes.

‘Help me,’ says a woman’s voice. Someone in the forest.

I climb back into my Hilux and pull over, half on the road, half off, and switch on my hazards. I don’t know this hillside forest, I have not stepped into its trees before. But I must check on this screaming woman. How can I not?

‘Hello?’ I shout out.

Nothing.

Chill around the back of my neck.

I jump a ditch that’s October-full of stagnant brown water, and enter the treeline. One tree deep. Three trees deep. Five.

‘Hello? Are you okay?

She screams again. No answer, just a guttural plea.

I turn and I can’t see my Hilux anymore, can’t see the road. No hazard lights, no headlights, no tarmac. The fog is rolling through on the breeze. It is the breeze. Misty waves stroking my face, dampening my hair. I use my hands to cover my hearing aids and then I yell, ‘I’m coming!’

I walk. I cannot run. I’d fall into a ravine and die. I’d slip on a rock and plunge headfirst into a freezing river. I walk and I focus on where I think the woman is, and let me tell you I am not well qualified for this task. Not in twilight. Not in autumn. Not in fog-riddled woodland.

Sobbing. One of my hearing aids is damp and it’s giving me feedback.

‘Where are you?’ I shout.

‘Over here,’ she says, and I could almost laugh if this situation wasn’t so desperate.

I trudge past stumps and trip over moss-crusted boulders. There are boggy stretches that hunger for my boots and my shins. I try to step on roots. Dry land.

I find a path of sorts and start to jog. My chest feels like it’ll explode; cold mist pumping down into my lungs and out again.

The slimy caps of wet mushrooms glisten in my peripheral vision.

She screams again. Unintelligible. Is she trapped by a bull elk? Held down by a man? Injured in some kind of animal trap?

I have no bearings. I could be anywhere. Nowhere. I turn on my heels and the next scream sounds like it’s from the other way. Is she moving around in this forest? Am I going round in circles?

I almost run face first into the house.

A damp, wooden structure with no windows at all on the ground floor. No door I can see. A painted doll’s house that’s been damaged in a fire rests on a tree stump. It’s sat a little way from the main building. The kennel-size roof is blackened and the tiny furniture inside is singed. I look around at the real house. Lots of windows upstairs but no way in or out. What is this place? Some forest-ranger station? Green pollen and mould rising up from the forest floor, trying to reach up to those high windows. A bronze clock bolted onto the gable end; a clock with no hands to tell the time with.

‘Please,’ says the voice. ‘You have to come.’

The voice is close. Is she inside the house?

I turn a quarter circle and listen to her voice and then I run. To where I think she is. I have my phone and the knife Benny Björnmossen sold me last year. I run.

‘Keep talking,’ I yell, gasping for breath. ‘I can’t see you in the fog.’

And so she does. She whispers continually. Droning. Chanting. Is she injured? Or is this whole thing a trap?

I dash through birches and around pine trees, their dead lower branches scratching at my neck, drawing blood on my wrist.

She’s whispering now.

I can barely hear her.

‘I’m nearly there,’ I yell, but I have no idea where ‘there’ is, just as I have no notion of where ‘here’ is either. Drop me in a forest and I’m likely to fall down and give up, but throw in thick fog and I may as well…

An arm catches round my neck.

I fall.

Wet moss and pine needles.

A body on top of me. Heavy. Smells of waxed jacket. A forearm to my face.

‘Get off me!’

‘Please,’ she says.

I roll away and she is staring at me, her eyes bulging and red, her fingers bloody.

‘Please.’

‘Who are you?’ I ask, the fog managing to drift between us, her face breaking up behind the static.

She gets to her knees and stands and I see her jeans are red. Stained. Splattered.

I pull my knife from my bag and she says, ‘No,’ and puts her palms to her face, and she says, ‘No, no, no.’

I take a deep breath of forest air, dense with spores and rotten leaves. It’s thick autumn air laced with the tang of rot and decay.

‘Over there,’ she says, pointing into the mists.

I swallow hard and stand up and move to where she’s pointing.

A fallen pine, its root system flat and sprawling like a metro map. A dash of colour behind. A coat?

I clamber over the pine, its rough bark scratching at my trousers like the nails of a grasping hand.

Two boots.

And two legs.

‘Dead,’ she says.

I look back and see the woman properly for the first time. She’s shaking her head. No coat. Just a haunted expression.

‘What happened here?’ I ask. But she just points harder, her blood-tipped index finger stabbing into the fog.

She doesn’t come to where I am. She stays back.

My foot plunges into a deep pile of leaves and brown, acidic water fills my boot.

‘Call the police,’ I say.

‘No phone.’

I take out my phone and dial Gavrik police. ‘It’s me, Tuva Moodyson. Halfway up Visberg hill. You’ll see my truck. Fifteen minutes into the forest on the north side. Near a house with no ground-floor windows. A body.’ I end the call because what more is there to say.

The woman keeps back and I don’t trust her yet. I don’t like the look of her scarlet hands.

The body is resting on granite, not earth.

Covering the rock is a thin layer of saturated, bright-green moss. A blanket.

The head is hidden by a coat, probably the screaming woman’s coat, but I can tell this is a man’s body. From his boots, his hands, his shape.

I turn back to her. ‘The police are on their way.’

She just looks at the coat covering the top half of the body, at the reflective patches now red with fresh blood, and she chews on her lip and shakes her head from side to side. I’m losing her to these mists. She’s two metres from me and she’s now just a ghost of a person.

The dead man’s wearing black jeans. Rubber boots. His coat is open to reveal his blood-soaked beige sweater. No wedding ring. His palms face up. A single fallen pine needle rests along one of his lifelines, nestled in the crease of his motionless hand.

I kneel down.

Next to my knee is the crisp curve of a copper beech leaf and sitting within its cupped form is a pool of human blood. No animal is troubling it. There is no ant or fly arriving to fulfil a basic destiny. It’s perfect. Obscene.

I reach out to lift the corner of the coat covering him, and the woman lets out a ghoulish bark.

A warning.

‘I need to check for a pulse,’ I say, although looking at the wound on this man’s chest, the amount of blood loss, I know it’s a preposterous notion. He is lifeless. But I must. Even here in this hillside forest, we must hope.

‘No,’ she says.

The fog drifts past her and I see the dread in her eyes, the blood on her face now that she drags her fingers across her damp cheeks.

I turn back to her coat, careful not to disturb the bloody beech leaf.

I hold the coat by the zip toggle and lift it a fraction.

My fingers automatically connect with his skin so I can take a pulse.

I move the coat higher and throw it to one side.

No pulse.

And no head.

Chapter 10

The drive to Visberg takes over an hour on account of a lumber wagon picking up felled pine trunks close to the sewage works.

I’m lost in thought. The awful facts as presented to me a few hours ago by Noora. The chainsaw theory. And now the realness of me talking to the victim’s ex-wife. It never gets easier. I try to prepare, to be mindful of what she must be processing right now. Shock morphing into disbelief morphing into acceptance and loss. I tap into my memories of when Dad died. Me, a fourteen year-old. An only child. Being told by a policewoman that my father had been killed in a head-on collision with an elk. The impact that had on Mum. The impact it still has on me to this day.

My truck begins the ascent. Gradual at first, almost imperceptible. I pass Svensson’s Saws & Axes and its sign says ‘Out felling! Back in 10’.

The road winds higher and higher.

There’s a tractor up ahead with a special attachment you probably wouldn’t see in many other corners of the world. The tractor is stabbing down sharp orange poles into the soft earth either side of the asphalt. Like slalom ski poles. Orange sticks with reflector stripes to stop people like me driving straight into an icy ditch when the white months arrive. Which they will. Soon.

Higher. No fog today but low clouds sit over the town like a malevolent breath from above.

There aren’t any vehicles close to where I parked that night. Just the white bike. That ghostly memorial to an anonymous fallen cyclist. A pedal bike spray-painted white and left on the side of the road for all eternity. A reminder to us all. A vision so stark we take a moment. Lose a breath. Rethink our priorities.

I pass a bus shelter with two teenage girls sitting side by side, each one wearing a bobble hat. Yellow and blue. I pass a cross on the opposite side of the road. Another memorial. With fresh flowers and a slice of pizza ejected from some truck window I don’t know when.

Visberg square is empty.

Apple trees creaking, an unoccupied bandstand, that giant bee rotating on top of Hive self-storage. The pizzeria owner is taking a crate of fresh tomatoes from a guy in a van. There’s a mobility scooter parked outside the pharmacy, small dog attached. But no pedestrians.

I drive on past Konsum and beyond the square. A barber shop with two chairs and two cylindrical glass jars full of bright-blue barbicide; the black combs inside like coral from some deep-sea trench. Two barbers, one in each chair. Zero customers. Two copies of the Gavrik Posten.

My GPS tells me I have reached my destination. Or rather, ‘Your destination, you have reached,’ because I downloaded a new Yoda SatNav package.

Number 36.

Grey-painted door. Grey-painted house.

I knock and the door immediately flies open.

‘Are you Tuva?’

Blonde woman, hair almost as fine as mine. Narrow shoulders, a large beauty spot above her upper lip. Tired eyes. A pained smile.

‘Yes, Mrs Persson. I’m so sorry for your loss.’

‘Come inside off the street.’

She’s wearing Nike Air Jordans. Either originals from the ’80s or reissues.

‘Coffee?’

‘Please.’

We sit down at her kitchen table. Four chairs. A rubber polka-dot cloth. Thermos. Plate of digestives.

‘Your colleague said you wanted a few words for the newspaper,’ she says. ‘About Arne.’

She puts her palm to her eyes. No sobbing or appreciable tears, but she is hiding her gaze and holding tight on the side of the table.

‘If you feel up to it. I wanted to give you a chance to say a few things. To remember Arne to the town.’

She nods, her palm still clamped to her face. Then she removes it and says, ‘I’m sorry.’ She smiles a broad, beautiful smile and says, ‘We weren’t even married anymore.’ Her smile breaks out into a stunted laugh. ‘But I still loved him. That doesn’t go away so easily.’

I take out my Dictaphone.

‘I’m deaf, you see. I don’t want to mishear your words.’

‘Of course.’

‘Arne took up walking in the boar forests earlier this year. He wanted to get fit, even though he’s been pretty fit all his life. Soccer and plumbing.’ She looks at me. ‘That’s why he was in Visberg forest that day. On that steep hillside.’

‘What do you think happened, Annika. I mean, do you have any theories? Did Arne have any enemies you know of?’

She looks up at the ceiling. ‘I’ve told the police all I know.’ She looks at me again. ‘He had scuffles and scraps in the past. He spoke his mind, you see, didn’t back down from an argument. But most people liked Arne. He helped people out if they were in a fix. Generous with the money he had. Always very generous with his tenants and friends. He’d help out if he could.’

‘Did he have any fights or arguments recently?’

She sips her coffee.

‘Not recently that I know of, but we haven’t been speaking regularly. The divorce only went through last year.’ She glances out the window. ‘Arne never got on with Dr Edlund, the town dentist. They played off in a charity golf competition over near Torsby a few years ago, not the Edlund’s course, a public one. Sven was there in his plus fours with his 50,000-kronor clubs, each one monogrammed. All the latest gear. He’s part owner of the local private course, see. And Arne beat him with his father’s old bag of clubs. Wooden things and old broken tees.’ She chuckles and a tear appears on her lid. ‘Sven Edlund never lived it down.’

‘Any other run-ins? Any rivalries or bad blood?’

She pours us both more coffee.

‘It’s probably nothing.’

I stay silent. One of Lena’s tricks.

‘He’s had an ongoing issue with Hans Wimmer, the German clockmaker on the square.’ Hans is Austrian, but I let that go. ‘Arne inherited an old pocket watch from his father. It was a Longines. Over a hundred years old. Not terribly valuable but it was his prized possession. Anyway, Arne took it to Hans for a service because it had stopped working. Hans Wimmer told Arne it was a fake, a re-dial or something, the parts had been messed around with, probably fifty years ago. Not original. Arne took that as a slur on his father’s legacy. They never spoke again after that.’

‘Thank you, Annika. Is there anything else? Any other detail?’

‘I don’t know if I should say.’

I wait.

‘I heard he had a thing with a woman in the town, after we were divorced, I’m certain he was faithful when we were married.’

‘Go on.’

‘I never found out who the woman was. But it ended badly, that’s what I was told.’

‘Who told you?’

She shakes her head. ‘I’d rather not say. Doesn’t matter who.’

‘You have any idea who he was seeing?’

‘Well, I was talking to Sheriff Hansson about this, not about her exactly. But I do find it odd that the killer stole Arne’s wedding ring.’

I did not know this. I sip the coffee and try to look like I did.

‘I mean,’ says Annika. ‘I know it’s strange that he still wore it after we divorced, but really it has no financial value whatsoever, so why would the killer take it off his finger?’

‘Are you sure he was wearing the ring?’

‘He always wore it,’ she says. ‘Sheriff reckons his finger was scratched up, pressure marks from someone pulling it over his knuckles.’

She squeezes her eyes together and wrinkles up her face.

‘That’s terrible.’

‘And people round here will try to point the finger at Luka Kodro, the restaurant owner, but they’re just narrow-minded.’

‘Why would they point a finger at Luka?’

She frowns and swallows hard and says, ‘Luka and I…’ she pauses. ‘We had an affair a few years ago. I’m not proud of it, but it happened. We broke it off after a couple of weeks. We told our partners. Arne couldn’t accept it, despite the fact he was no angel, always had an eye for the ladies. Luka’s wife did accept it, I suppose. But Luka wouldn’t hurt a fly, he’d have no reason to do something horrendous like that to Arne.’

We finish up the interview and she shows me to the door.

‘Thanks again for the coffee and for talking to––’

‘I still loved him, you see,’ she says. ‘Arne was a good man, really. Better than I ever deserved. It didn’t work out between us but I still loved him.’

I leave my Hilux where it is and walk over to the Hive self-storage building. Its door is propped open with a black cinder block.

I peer in.

An apple drops to the ground behind me with a thud.

‘Anyone here?’ I ask.

The guy from yesterday approaches slowly.

‘How can I help?’

Emil Eriksson is a whole head shorter than me. Thick bushy moustache that doesn’t quite fit his face. Side parting. Plimsolls. A candy bracelet on his wrist.

‘I wanted to introduce myself. I’m Tuva…’

‘Who’s this, Emil?’

A woman strides in wearing a fitted maroon dress and high heels.

Emil looks at me then back to her.

‘I’m Tuva Moodyson. My newspaper over in Gavrik just merged with the Visberg Tidningen so I’ll be covering the town news from now on. I wanted to introduce myself.’

‘Taking Ragnar’s job more like it,’ she says. ‘Ragnar Falk, smells of talc.’

I frown. ‘No, it was more like he sold––’

‘I’m just having a laugh. The name’s Margareta Eriksson, pleased to meet you. This is my son, Emil. Say hello, Emil.’

Emil says, ‘Hello, I’m Emil.’

No shit, Emil.

‘We’ve owned the Hive since 1989. My late husband found this fascinating historical property,’ she looks around her, ‘advertised in Dagens Industri. We’re proud to say we’re the leading independent self-storage business in all of Värmland.’

‘Are you here about the dead plumber?’ asks Emil, looking up at me.

‘Ah, yes,’ says his mother. ‘Of course you are. I’m sleeping with a carving knife under my pillow from now on. Can’t take any chances.’

‘I’m just introducing myself to the town,’ I say.

‘They cut off his head and his hands,’ says Emil, adjusting his bracelet. ‘With a chainsaw. No prints, you see. No way to identify Arne with no hands or head.’

I frown again and say, ‘But Arne has been identified.’ I want to explain that the hands were not removed, but I’m in no position to divulge those details. That’s police business. Maybe if his hands had been cut off he wouldn’t have been identified so quickly.

‘Killer underestimated the Feds,’ says Emil. ‘That’s what I’m trying to tell you.’

‘Would you like to run a story on us?’ asks Margareta. ‘A feature, perhaps? Ragnar Falk smells of talc always despised us. Never so much as let us in the paper unless it was a paid-for advert. Would you like a feature? An exclusive story?’

‘What about?’

She turns on the spot and spreads her arms and bellows, ‘What about? Just look at this place, the stories in these walls. Centuries of history. The things I could tell you, Tuva.’

‘Always happy to listen,’ I say. ‘Once we’ve got to the bottom of the murder on Visberg hill I’d love to chat.’

I hear the theme tune to Cheers in the distance.

She points at my face and says, ‘That’s more like it! Now I must go and open up a unit for a customer. Emil, show Tuva out, please.’

Margareta smiles and totters off with a set of keys in her hand.

I head for the door and say, ‘Nice to meet you, Emil,’ but he rushes past me and stands in my way, his small frame silhouetted in the doorframe, the whiskers of his full moustache backlit by the light from the street.

He starts to remove the candy bracelet from his wrist.

‘Please,’ he says, offering it to me.

‘No, thank you.’

He’s still blocking the door.

‘Please, it’s a custom here. Everyone gets one.’

I take the candy bracelet. The individual candies are coloured pastel pink and blue and green. There’s fluff stuck to them.

He moves aside.

As I pass by Emil to leave he raises his fingertips up under the shadow of his moustache and sniffs them.

Chapter 11

I head outside into the sunshine.

The Hive is so long it covers one side of the square. A whole block, I guess. Like a shit version of Harrods or Macy’s. With my back to the yellow-and-black building I can see the dark side of the street to my left, the sunny side to my right, the descent straight ahead of me. I walk toward the dark side of the square.

Margareta’s unlocking a large drive-in self-storage unit on the far side of the Hive. I wave and she looks away.

I deposit Emil’s candy bracelet in a bin.

The breeze is cool on my skin. I cross and stand outside the Visberg dental surgery. The window has a large cardboard sign inside, taped to the glass. It reads, ‘No Refunds.’

I open the door.

A reception desk with a woman sitting behind it reading a book. A fish tank. Two leather-clad benches. Two mannequins posed as if they’re reading magazines, the faded periodicals taped to their plastic hands. A coffee table stacked with copies of the Visberg Tidningen and Dam magazine. A kid’s play area consisting of a wooden box stuffed full with mangled dolls in various states of undress.

‘Good morning,’ says the receptionist.

‘Hi, I’m Tuva Moodyson. Eleven o’clock with Dr Edlund.’

She smiles and puts down her copy of Anna Karenina.

‘Let me just find your appointment.’

She puts on a pair of glasses and uses the computer. Her name badge says ‘Julia Beck’. She’s around my age, maybe a few years older, maybe thirty. Red hair’s up in a messy ponytail that suits her. Freckles. A relaxed demeanour.

‘Eleven o’clock it is. Take a seat, Tuva, and if you could fill out one of these please.’

She hands me a form on a clipboard with pen attached.

I sit down next to a mannequin and look at the receptionist.

Julia Beck smiles and says, ‘Susan and Linda are here to put people at ease.’

Well, Julia, that ain’t working.

I complete the form and hand it back to her.

‘You live in the big city?’ she says, checking my address on the form.

‘No, just in Gavrik.’

‘The big city,’ she says.

‘Small town.’

‘Oh, you’re too modest.’

‘Are you from here, Julia?’

‘Born and raised on this here mountain,’ she says.

‘Sorry about the awful news.’

Julia’s eyes open wide. ‘What. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...