- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

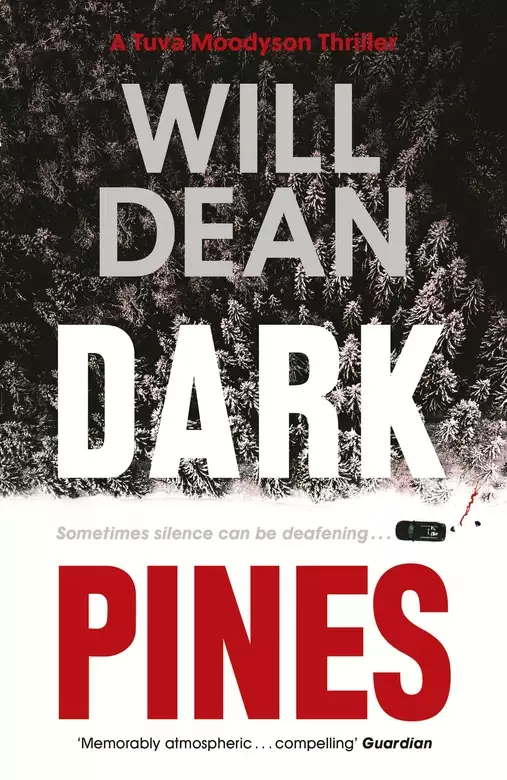

Synopsis

SEE NO EVIL

Eyes missing, two bodies lie deep in the forest near a remote Swedish town.

HEAR NO EVIL

Tuva Moodyson, a deaf reporter on a small-time local paper, is looking for the story that could make her career.

SPEAK NO EVIL

A web of secrets. And an unsolved murder from twenty years ago.

Can Tuva outwit the killer before she becomes the final victim? She'd like to think so. But first she must face her demons and venture far into the deep, dark woods if she wants to stand any chance of getting the hell out of small-time Gavrik.

Release date: May 1, 2023

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dark Pines

Will Dean

To my agent, Kate Burke: thank you for your energy and wisdom and skill. Thanks for giving me the chance.

To the team at Diane Banks Associates: thank you for your encouragement and warmth.

To my editor, Jenny Parrott: thank you for being whip-smart and sensitive and generous. Thanks for making this real.

To the team at Oneworld and Point Blank: thank you for being so dedicated and passionate. I could not ask for a more excellent publisher.

To all the bloggers and booksellers and reviewers and tweeters: thank you for your enthusiasm and time. Readers benefit so much from your recommendations and spirit. I am one of them. Thank you.

To the York Festival of Writing: thank you for teaching me things. Thank you for putting hundreds of writers in a room each year. Thanks to Julie Cohen and Shelley Harris for being stars.

To Claire McGowan: thank you for being a very early reader. Thank you for your encouragement and for your wise, succinct comments. You helped me.

To Hayley Webster: thank you for positive feedback years ago on a day I needed it most.

To Paddy Kelly: thank you for reading an early version of the book and for being so positive and kind.

To @DeafGirly: thank you so much for your expert feedback. In some ways your opinion matters to me more than anyone else’s. I am very grateful.

To the Swedish nature: thank you for being wild. Thank you for being an inspiration.

To my family: thank you for letting me play alone for hours as a child. Thank you for letting me read. Thank you for not enrolling me in countless clubs. Thank you for allowing me to be bored. It was a special gift.

To my friends: apologies if I’ve missed barbecues and parties due to rewriting. Thank you for being wonderful (and patient).

To my sister: thank you for saying ‘do you mind if I just wait for the movie.’

To my wife and son: Thank you. Love you. Always.

Chapter 1

Gavrik, Sweden

An elk emerges from the overgrown pines and it is monstrous. Half a ton, maybe more. I stamp the brake, my truck juddering as the winter tyres bite into gravel, and then I nudge my ponytail and switch on my hearing aids. I get the manufacturer’s jingle and then I can hear. The elk’s thirty metres away from me and he’s just standing there; grey and shaggy and big as hell.

My engine’s idling. I think of Dad’s accident twelve years ago, about his car, what was left of it, and then I punch the horn with my fist. Noise floods my head, but it’s not the real sound, not like you’d hear. I get a noise amplified by the plastic curls behind my ears. The horn does its job and the bull elk trots away down the track with his balls hanging low between his skinny grey legs.

I speed up a little and follow him and my heart’s beating too hard and too fast. The elk walks into a patch of dappled sun up ahead and then stops. He’s prehistoric, a giant, completely wild, ancient and taller than my rented pickup. I brake and thump the horn again but he doesn’t look scared. I’m panting now, sweat beading on my brow. Not enough air in the truck. There are no police here; no headlights behind me and none in front.

The fur that coats his antlers glows in the sun and then he swings his heavy head around to face me. His posture changes. Utgard forest darkens all around me and he stamps his hoof down and breaks a thin veneer of ice covering a pothole. My headlights pick out a splash of dirty water hitting his fur and then he looks straight at me and he drops his head and he charges.

I brake and pull the gearstick to reverse and slam the thick rubber sole of my boot down on the accelerator. My scream sounds alien. The truck pushes backwards and opens up a clear space between me and the bull elk; between my face and his face, between my threaded eyebrows and his rock-hard antlers.

I lift my phone out of my pocket and place it on my lap even though everybody knows there’s no reception in Utgard forest. My eyes flit between the windscreen and the rear-view mirror. I’m trying to look in front and behind at the same time, and there’s a flash of movement in the trees, something grey, a person maybe, but then it’s gone. This is all my fault. I should never have driven after this elk. I see dull sky through his antlers and somewhere inside I reach out for Dad. I hit potholes and fallen branches and those black eyes are still there in my headlights. Thirty kilometres an hour in reverse gear. My phone falls off my lap and rattles around in the footwell. I reverse faster. The light levels are dropping and the elk’s still coming straight at me. My left tyre gets caught by the edge of a ditch and I have to turn hard to jump out of it, and then his antlers touch my bumper, metallic scratches piercing my ears, and I can’t see a damn thing. I feel a stick of lip balm digging into my thigh and then my mirrors flash and it’s someone else’s headlights.

Behind me in the distance there’s a truck or a tractor, something driving straight at me. It should be a welcome sight but it’s not. This track’s only wide enough for one of us. The antlers scrape my bonnet again and I wince at the screech. My mouth’s dry and I’m hot in my sweater. I’m reversing into a crash with an elk in my face.

And that’s when I hear the gunshot.

The elk bolts to the trees and he jumps a ditch and flees into the darkness of the woods. The last thing I see are his rear legs as Utgard forest takes him back.

My palms are sweaty and the steering wheel feels damp and slick. I brake but keep the engine ticking over. The vehicle behind me, perhaps a quad used by a hunt team to haul out a fresh kill, has turned off into the pines.

‘Breathe,’ I tell myself. ‘Breathe.’

I’ve been saved by a rifle shot on the first day of the elk hunt. Three years ago, in London, that sound would have been a headline and it would have been horrific. Now, here in Värmland, in this life, it’s normal. Safe, even.

I pull my sweater over my head and it gets tangled in the seat-belt. I fight with it for a while, hot and flustered, before pulling it loose. Strands of fine blonde hair float up from the fabric on a breeze of static.

I push the gearstick forward and drive. Not as fast as before, and not as fast as I’d like, but carefully, headlights on full beam, eyes glancing into the dark places at the side of the track. And then I’m swinging the truck up and onto the asphalt road and back towards Gavrik town. The traffic on the E16 is still gridlocked but from now on I’ll stay on the motorway. No more shortcuts. No more parallel forest roads.

I’m tired and hungry and the adrenaline in my blood is starting to thin. I’ve got thirty-two hours to write up eight leading stories before we go to print on Thursday night. I dip my headlights and I can still hear the sound of antlers scraping my bonnet. I pass the sign for Gavrik and the streetlights begin. Civilisation returns in layers. First cat’s eyes and lines down the centre of the road, now municipal lighting. Unlit forests can keep their fucking distance. I want pavements and cafes and cinemas and fast food and libraries and bars and parking meters. I want predictable and I want man-made.

I pass between the drive-thru McDonald’s and the ICA Maxi supermarket and head onto Storgatan, the main street in town. My pulse is slowing down but I keep getting flashbacks to Dad’s crash. And I wasn’t even there. My memories are lies, the images solidifying over the years. I drive on. The twin chimneys of the liquorice factory loom in the background like the spires of a cathedral. Shops are closing and staff are saying goodnight in as few words as possible before they shuffle off, collars raised, to their Volvos and their homes and their underfloor heating and their big-screen TVs.

My parking space is marked with my name, but if it wasn’t it wouldn’t matter. The town is over-catered with parking facilities. It’s future-proofed, but nobody knows if and when that future, the future where Gavrik grows by fifty per cent, will ever happen. Why would it? Those who grow up here, leave. Those who visit don’t seem to return.

I lock my truck and open the door to Gavrik Posten, the town’s newspaper and my place of work. Weekly circulation: 6,000 copies. I didn’t expect to end up here, but I did. I interviewed at four decent papers all within a three-hour radius of Mum and I got four offers. My mother lives in Karlstad and her family consists of yours truly so when she got sick I moved back from London. It’s not easy, she is not easy. But, she’s my mum. Gavrik’s close to Karlstad but it’s not too close and Lena, the half-Nigerian editor of the Posten, is someone I can learn from. The reception is two chairs and a dusty houseplant in a plastic pot, and a counter with a brass bell and an honesty box.

Lars, our veteran part-time reporter, isn’t in. I flip the counter – a slice of pine on a squeaky hinge – and hang up my coat. My fingers are still shaking. I kick off my boots and slip on my indoor shoes. The front office is two desks, one for me and one for Lars. Then there are two back offices, one for Lena, and one for Nils, our pea-brained ad salesman. Altogether, it’s a shithole of an office but we turn out a pretty decent community paper each and every Friday.

I don’t want to live in Gavrik. But I do. Mum needs me although she’s never said as much, not even close. It’s spread to her bones and her blood and if I can do tiny things – bring her the rose-scented hand cream she loves, read to her from her favourite recipe books now that she finds it too tiring, bring in fresh cinnamon rolls for her to taste – then I will. I’m not good at all this, it doesn’t come naturally to me just like it never came naturally to her. But I do what I can. And then one day, one sad-happy day, I’ll return to the real world, to a city – any city, the bigger the better.

‘Tuva Moodyson,’ Nils says, stepping out from his office. His hair’s spiked with gel like a teenage boy’s and his shirt’s so thin I can see his nipples. ‘What happened to you? Go home for a quick roll between the sheets, did you?’

I sit down and realise my T-shirt’s still sticking to my skin with sweat and my hair’s all over the place, strands plastered to my face, my ponytail falling apart. I’m a mess.

‘Just a quick threesome,’ I say. ‘Would have invited you to join us, but there were criteria, so . . .’

He looks a little confused and slowly closes his door, returning to his office which is actually the staff kitchen.

I wake my PC from its slumber and find the articles I’ve written and those I’ve just titled and outlined. I hear a beep in my left hearing aid, a battery warning, the first of three before it’ll cut out and leave me with the ten per cent hearing I have remaining in that ear.

Behind my PC’s anti-glare screen, I have eight Word documents stacked one behind the other. A local nursery is expanding, creating three more childcare places and one new job. The facade cladding of a block of apartments near mine is being rebuilt because the original wasn’t fit for Värmland weather and it’s coming off in chunks like flakes from a scab. The local council, Gavrik Kommun, has decided we can make do with one less snowplough this winter. It’s keeping two extra farmers on standby. The contest for the 2015 Lucia is underway and applications need to be sent to the Lutheran church on Eriksgatan by the end of the month. There’s a Kommun-wide tick warning because of a spike in Lyme disease and encephalitis cases. The critters will be frozen dead soon but thanks to a mild September we still have a few more weeks of their company. Björnmossen’s, the largest gun and ammunition store in town, will stay open two hours later than usual for the first week of October so hunters not taking time off work can still buy their supplies. There will be a handicraft fair in Munkfors town on October 21st. Finally, the story I’ve been working on today, the unveiling of a new bleaching plant at the local pulp mill, the second largest employer in the area after the Grimberg liquorice factory.

That’s my news. That’s it. Derived from rumour and council minutes and eavesdropping in the local pharmacy. It may sound pedestrian but it’s what my readers want. How many times have you torn out an article from a national paper and stuck it to your fridge? How many times have you cut out a piece from your local paper, maybe your daughter scoring in a hockey match or your neighbour growing the town’s longest carrot, and stuck that to your fridge? My readers give a shit and because of that, so do I.

Lars walks in and the bell tinkles and he starts to peel off his old-man coat.

I’m writing so I switch off my aids to concentrate. The fabric of my T-shirt is loosening from my skin and I’m starting to feel normal again. I can smell my own sweat but my deodorant masks most of it. If I was still interning at The Guardian, I’d have freshened up, but here, no. It’s okay. Not a priority.

Lena’s door opens.

She’s standing there. Diana Ross in jeans and a fleece. Her eyes are wide and she’s saying nothing.

‘What?’ I ask.

She holds her hand over her mouth. She’s shaking her head and speaking but I can’t see her lips. I can’t read them.

‘What?’ I say, fumbling to switch on my hearing aids. ‘What’s happened?’

Lena takes her hand away from her face.

‘They’ve found a body.’

Chapter 10

My pillow alarm shakes at 7am. I stare at my face in the mirror and it’s a puffy mess. Eye drops. The bottle says one to two drops in each eye but I use half the bottle.

Breakfast is five digestive biscuits and a mug of tea. I need to go shopping. I shower and clean my aids and dress and then plug in my aids and grab my bag. I slam the door shut on my way out.

I googled Freddy’s sister’s address yesterday. Even in a small town of 9,000 people, I don’t know every street yet, not like the locals do. I drive past identical semi-detached wooden houses with small, well-maintained gardens. Number 43.

A woman answers the door and I know it’s her before she even opens her mouth. Her make-up is on and it’s pretty good but it can’t hide her eyes or the effort it takes for her to smile. She looks like she’s been punched in the stomach a hundred times.

‘Tuva, come in, I’m Esther Malmström.’

We step inside. Shoes off.

The house is quiet and there are too many flowers. I can see she’s run out of vases. Some of the bouquets are identical because there’s only one proper florist in Gavrik town. Bunches of lilies sit in buckets, and by the stairs there are long-stemmed white roses leaning unceremoniously in a deep saucepan.

‘Please, let’s sit in here. Thanks for coming to talk to me.’

She leads me into the living room. Ikea sofa, big wall-mounted TV, log-burner, monochrome wallpaper on one feature wall.

‘I’m sorry for your loss,’ I say. ‘I’ll try to keep this brief.’

‘It’s all right,’ she says. ‘I want to talk to you. I want them to find the bastard who did this. Small town like Gavrik, we have to pull together and find out who did this to Freddy.’ Her smile cracks. ‘I’m ready and I want to help.’

‘Okay, I appreciate it. Esther . . . did your brother ever mention to you that he was afraid or that someone had threatened him?’

‘Cops already asked that,’ she says, stroking her palm against the arm of the sofa. ‘Not that I know of. He was a friendly guy, a school teacher. Everyone liked Freddy. He was a saint, really. I was always the bad one.’

I frown.

‘When we were kids, I mean. Freddy was a goody-two-shoes.’

‘Has he ever been attacked before? Any fights that you know of?’

‘No.’

‘People are linking this murder with the ’90s killings. Do you think they’re connected?’

‘Are you serious? Of course they’re connected. You think there are two freaks out there who take people’s eyes out? Cops didn’t find the killer back then and now he’s come out again and,’ she looks up at the ceiling and lowers her voice, ‘of course it’s the same guy.’

I’m quiet for a second.

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know about that.’

‘I had to identify him, didn’t I. Thought it’d be a curtain pulled back and all, thought I’d be able to say goodbye to him properly.’ She sniffs. ‘But it was just a photo. And they’d covered up his eyes so I think that tells you everything you need to know.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Yeah, me too.’

I pause.

‘Esther, did Freddy have any friends that you considered to be dangerous? Anyone you didn’t like?’

She stops stroking her palm against the armrest and looks at it. Then she looks at me.

‘Well.’ She goes back to staring at her palm as if waiting for it to take over. ‘Perhaps.’

My stomach rumbles and I squirm in the armchair to try to stifle the sound, but it carries on. It’s a preposterous noise and obscene in the circumstances.

She rubs her eyes, and with her hands covering much of her face, continues to talk. I can’t get the words. No lips to read, no clear speech.

‘I’m really sorry,’ I say. ‘I’m deaf and I didn’t quite catch your last words.’

‘You’re deaf?’ she says, eyebrows high on her forehead. ‘But, you can hear me?’

I point to my ears.

‘I can hear pretty good with hearing aids, and I lip-read as well, as a back up.’

‘You talk really well for a deaf person.’

She says this with kindness but my gut tightens anyway. It’s like saying to a man with a prosthetic leg, ‘Hey, you walk pretty well for a cripple.’ It’s not a compliment. It’s just not.

‘You were talking about Freddy’s friends, maybe one that you didn’t like or trust?’

‘Can you sign?’ she asks.

I shake my head.

‘What’s it like?’

I sniff. ‘You mean, being deaf?’

She nods and moves forward slightly on her sofa.

‘It’s like being you, but not being able to hear. It’s no big deal, I’ve been deaf since I was a little kid.’

‘Why? I mean, how did it happen?’

‘Meningitis.’ I have flashbacks to the things I remember hearing: a birthday party, an ice-cream van, the sound of Dad laughing. ‘I don’t mean to sound rude, but I really want to write a good story for you, so we can have people call us or write in with information about Freddy. Can you tell me about his friends, please?’

She sits back in the sofa and slides one hand down between the cushions.

‘Freddy and I were always very close, we told each other everything. There were two of his friends I didn’t like and he knew it. One was Hannes, his hunting buddy.’

‘Hannes Carlsson from Utgard forest?’

‘Yeah, he owns most of it. Him and his wife have a very good economy.’

There’s that phrase again.

‘They’re some of the richest in the Kommun,’ she continues. ‘But, he’s a bully and he bullied my friend’s husband when he worked up at the pulp mill. I reckon, he’s the hunt leader you know, I reckon he bullies his whole team.’

‘Do you think he’s responsible for Freddy’s death?’

She shrugs. ‘I don’t know. I told the cops to talk to him, to check his guns, but you know . . . they’re all real good mates with Hannes. He’s the big fish and they all want to be friends with the big fish and hunt his woods. I told them but I don’t know.’

‘Who is the second person you were unsure of?’

‘Don’t know her name, not her real name. “Candy” is what she goes by, works up at the strip club on the E16, you know the one stuck out in the middle of nowhere, little way south of the SPT pulp mill. That place used to be a brothel, did you know that?’

‘I didn’t.’

‘Well, you do now and I reckon it still might be some kind of brothel . . . unofficially somehow. You know what strippers are like.’

Actually, I don’t.

‘Fred and Candy were . . .’ I pause and look down at my Dictaphone for a split second, ‘friends?’

‘They weren’t friends, no. He was paying her. They were not friends. He told me he couldn’t afford it, but he couldn’t stop going either. Reckoned he was in love with her. I told him he was being a drip, falling in love with a goddam stripper but that was what happened. He spent two, maybe three nights a week up at that dive, drinking Diet Cokes and watching her dance.’ She wipes a tear from her eye, or it could have been an eyelash. ‘Not much of a life was it, really.’

I chew on my lip and look around the room. Photos in white wooden frames, a low bookshelf half-filled with board games and jigsaw puzzles.

‘Must be hard being a divorced man in his fifties in this town,’ I say.

She nods. ‘His boy’s upstairs, you know. He’s upstairs playing his damn computer games right now. Won’t come down. Doesn’t want to talk about it.’

‘How old is your nephew?’

‘He’s fourteen going on twenty-one. Won’t let anybody in, won’t talk to no one. I have to leave his food outside his door like he’s a monk or a prisoner or something. His mum’s in Florida and he’s heading off there at Christmas time. I think that should do him some good, although he don’t like her much.’ She looks up to the ceiling and lowers her voice. ‘I can’t blame him for that.’

‘If you want, I can try to talk to your nephew? I’m only twelve years older than him after all and I know all about video games.’

‘I don’t know . . .’

I say nothing. One of Lena’s many tricks.

‘Well, I guess you could try,’ she says. ‘Can’t do any harm, just for a minute.’

She leads me upstairs and knocks on the boy’s door.

‘You decent, Martin?’ she says.

No response.

‘You decent in there, Martin?’

‘No,’ he shouts back.

‘Okay, he’s decent. I’ll be out here.’

I push the bedroom door open and see a lanky kid lying on the floor playing Call of Duty on his PlayStation. I glance at him but then focus solely on the screen.

‘You wanna upgrade to the RPG,’ I tell him. ‘And you wanna watch your back.’

He looks up at me for a moment, console in hand, then turns back to the TV. His eyes are red. I’m not sure if that’s from tears or gaming.

‘You a journalist?’

‘I’m Tuva . . . Watch your back, I get ambushed just here every fucking time.’

He looks at me and sniffs and then he pauses the game.

‘You gonna write about my pappa?’

I nod.

He swallows hard. ‘You know they scooped out his eyes. And his eyes looked just like my eyes, too. Blue-grey. Mum says we have the same eyes. Exactly the same. That’s what she says. None of this feels right, it’s like he might come back home anytime, just walk back in. But that’s bullshit, I know that. And I’ve got the same eyes as him. The exact same colour. I might be next.’

He points to his eyes.

‘No,’ I say, louder than I’d intended. ‘No, that’s not going to happen, Martin. You’ll be safe here.’

‘Mum’s not here and Dad’s gone,’ he says. ‘All my mates think that writer did it.’

‘Which writer?’

‘Freak who lives in the woods. My mate’s big sister works in ICA. Freak comes in every week, same day, same time. Freak always comes to her till, she reckons he fancies her. Freak always buys a load of the weirdest stuff. He doesn’t get nachos and potatoes and ham and normal shit. This writer freak buys pigs’ feet. He buys the tails too, even the ears. Who buys pigs’ ears?’

‘Well,’ I say. ‘I’m sure the police will be talking to everyone in the village so they’ll be speaking to him. But some people do cook offal and the cheap cuts. Not me, but it’s not as uncommon as you might think.’

‘He’s a freak,’ he says. ‘Put that in your paper.’

Esther Malmström steps to the doorframe.

‘You hungry, Martin? Want me to fix you a sandwich?’

He nods at her.

‘Thanks for talking to me, Martin,’ I say, and I feel like the policewoman that spoke to me on the night Dad died. ‘I’m going to finish my chat with your aunty now. I’m sorry about your pappa, I really am. I want to help get to the bottom of this. I promise you I’ll do whatever I can.’

He unpauses the game and I close the door.

Esther leans in towards me at the bottom of the stairs and talks softly into my hearing aid.

‘He can’t talk about it with his mates because they’re all fourteen years old,’ she says. ‘And he can’t talk about it with me or any other grown-up because he’s fourteen years old. You think he’s got a point about that writer?’

The smell of lilies hangs in the air. Do we have one killer in this town or a copycat? Why the hell is there a twenty-year pause?

‘I don’t know if he’s got a point. But I’ve been assigned to write about this and it’s the only thing I’m working on. I’ll try to help find out who did this so you can all get some justice and some closure. What Martin said, well, kids say some weird things, but I’ll certainly check it out. I’m heading over to Mossen village this afternoon.’

Chapter 11

After my sandwich, a cling-filmed margarine crime from the newsagent’s fridge, I check in with Lena.

‘It’s post-mortem day,’ she says. ‘Bumped into Chief Björn out on the street. His people have been tracing the last movements of Malmström, checking if anyone noticed anything unusual.’ She leans back in her chair. ‘Reckons the forensics guys found very little in Utgard, what with the rain and all the boot prints from police and paramedics. It was a muddy mess.’

‘Any physical evidence? Fibres?’

‘Björn wouldn’t say but I could tell by his face it’s not looking good. If Freddy was shot by a hunting rifle, the killer could have been hundreds of metres away. They’ll do the bullet analysis, try to fix the direction it came from, but it’s not like a city-centre murder with CCTV and witnesses, nothing like that.’

She looks up at me.

‘I got some good material from the sister and a list of rumours as long as my arm.’

She nods. ‘Okay.’

‘And two more houses to visit in Mossen.’

She nods again and I leave.

On the drive to Utgard forest, I notice a few features that I missed before. In the underpass beneath the E16 motorway, someone’s hung a piece of knotted string, threaded through CDs. Some kind of scarecrow, I guess. Orange plastic poles are dotted along each side of the road to mark the edge of the ditch for when the winter snows come. I pass dozens of them. And then I turn right and I’m in Mossen.

I drive past Hoarder’s place and see nothing. When I look into the woods I realise I may as well be looking at Alaska right now, or Siberia a thousand years ago, or Norway in a hundred years’ time. There is no evidence of time. No markers or guides. It’s stark and vast and I cannot see past it. I look up through the windscreen and think of Dad and wonder again if the bullet that scared off my elk was the same one that killed Freddy Malmström. Will Call of Duty kid be okay with his dad gone and his mum so distant? Is he going to be me at that age: isolated, throwing every waking hour into studying and gaming?

The taxi driver’s house is still empty, no Volvo in the drive. I speed up the hill and notice some of the potholes have been filled with gravel, light grey pebbles humped where the holes used to be like fresh graves. I pass the sisters, both hard at work, the fire burning in between them, and pull up at the ghostwriter’s house.

The day is bright, on-and-off sunshine with a gentle breeze, and his house is one of the least foreboding in the village. It’s modern, ‘80s maybe. The veranda wraps the building in its entirety and partially obscures the windows, which all appear to be mirrored. Something about the place suggests it’s well built, more expensive than most homes in the area. In Gavrik Kommun, most houses are built by one of two companies so they tend to look roughly the same. This one stands out.

I ring the doorbell and wait. I can hear classical music of some kind from the other side of the door so it must be loud inside. I wait some more, checking for messages on my phone. No reception. I ring the doorbell again and then knock twice. The music turns off.

I think I hear a man shout ‘hello’ from the other side of the door but it’s unclear to me so I shout, ‘Hello Mr Holmqvist, I’m Tuva Moodyson from the Gavrik Posten. I wondered if I could talk to you for a moment, please? I’m deaf so can’t hear you through this door.’

There’s a long pause. I hear a gunshot in the distance, then another.

I hear bolts being clicked and then the door opens a little. A green eye and half a face, neat, clean-shaven, pale, with a faint scar above his lip.

‘Hello,’ he says.

‘Sorry to bother y. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...